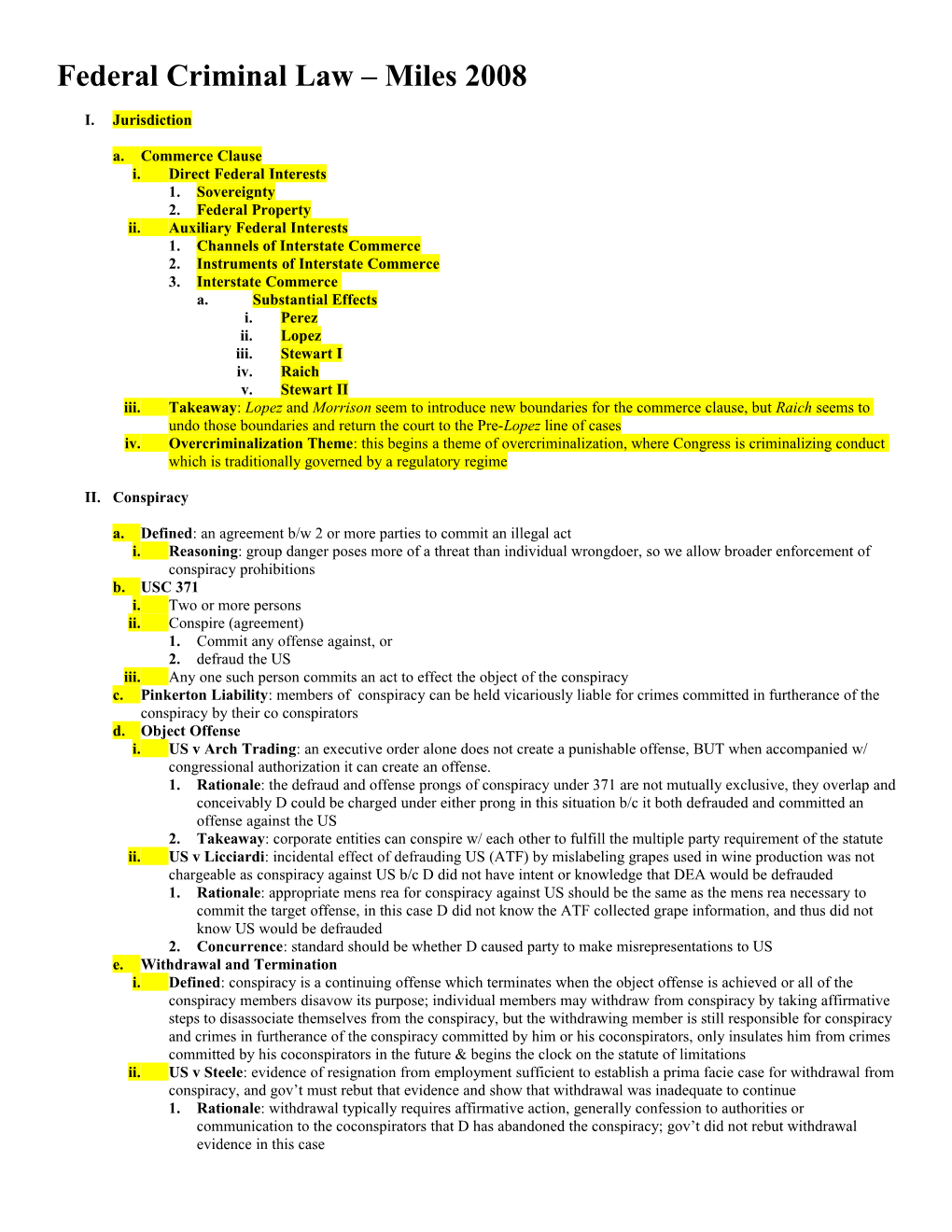

Federal Criminal Law – Miles 2008

I. Jurisdiction

a. Commerce Clause i. Direct Federal Interests 1. Sovereignty 2. Federal Property ii. Auxiliary Federal Interests 1. Channels of Interstate Commerce 2. Instruments of Interstate Commerce 3. Interstate Commerce a. Substantial Effects i. Perez ii. Lopez iii. Stewart I iv. Raich v. Stewart II iii. Takeaway: Lopez and Morrison seem to introduce new boundaries for the commerce clause, but Raich seems to undo those boundaries and return the court to the Pre-Lopez line of cases iv. Overcriminalization Theme: this begins a theme of overcriminalization, where Congress is criminalizing conduct which is traditionally governed by a regulatory regime

II. Conspiracy

a. Defined: an agreement b/w 2 or more parties to commit an illegal act i. Reasoning: group danger poses more of a threat than individual wrongdoer, so we allow broader enforcement of conspiracy prohibitions b. USC 371 i. Two or more persons ii. Conspire (agreement) 1. Commit any offense against, or 2. defraud the US iii. Any one such person commits an act to effect the object of the conspiracy c. Pinkerton Liability: members of conspiracy can be held vicariously liable for crimes committed in furtherance of the conspiracy by their co conspirators d. Object Offense i. US v Arch Trading: an executive order alone does not create a punishable offense, BUT when accompanied w/ congressional authorization it can create an offense. 1. Rationale: the defraud and offense prongs of conspiracy under 371 are not mutually exclusive, they overlap and conceivably D could be charged under either prong in this situation b/c it both defrauded and committed an offense against the US 2. Takeaway: corporate entities can conspire w/ each other to fulfill the multiple party requirement of the statute ii. US v Licciardi: incidental effect of defrauding US (ATF) by mislabeling grapes used in wine production was not chargeable as conspiracy against US b/c D did not have intent or knowledge that DEA would be defrauded 1. Rationale: appropriate mens rea for conspiracy against US should be the same as the mens rea necessary to commit the target offense, in this case D did not know the ATF collected grape information, and thus did not know US would be defrauded 2. Concurrence: standard should be whether D caused party to make misrepresentations to US e. Withdrawal and Termination i. Defined: conspiracy is a continuing offense which terminates when the object offense is achieved or all of the conspiracy members disavow its purpose; individual members may withdraw from conspiracy by taking affirmative steps to disassociate themselves from the conspiracy, but the withdrawing member is still responsible for conspiracy and crimes in furtherance of the conspiracy committed by him or his coconspirators, only insulates him from crimes committed by his coconspirators in the future & begins the clock on the statute of limitations ii. US v Steele: evidence of resignation from employment sufficient to establish a prima facie case for withdrawal from conspiracy, and gov’t must rebut that evidence and show that withdrawal was inadequate to continue 1. Rationale: withdrawal typically requires affirmative action, generally confession to authorities or communication to the coconspirators that D has abandoned the conspiracy; gov’t did not rebut withdrawal evidence in this case iii. US v Jimenez Recio: defeat of the conspiracy by law enforcement does not result in “automatic termination” of the conspiracy, so that members joining the conspiracy after the conspiracy has already been defeated can still be charged with conspiracy 1. Rationale: the defeat of the conspiracy does not eliminate the reasoning behind criminalizing conspiracy in a special way, which include the increased likelihood of further commission of crimes b/c of the group mentality of the conspiracy, and decrease in the likelihood that members of the conspiracy will depart from the path of criminality b/c of the group polarization effect

III. Mail Fraud

a. USC 1341 i. Whoever devises or intends to devise a scheme or artifice to defraud or for obtaining money or property by means of fraudulent pretenses ii. And for the purpose of executing such scheme or artifice places in any post office anything meant to be delivered by the postal service or private carrier 1. *** Defraud need not be a separate punishable offense, and is interpreted broadly b. USC 1343: wire, radio, and television fraud c. Schemes to Defraud i. Fraud v False Pretenses: 1. False Pretenses: encompasses false representation of a past or present condition to induce another to part w/ property, but not a future condition 2. Fraud: much broader than false pretenses – effort to gain undue advantage or to bring some harm through misrepresentation or breach of duty ii. US v Hawkey: public official who used some funds from concert organized for charity for personal use sufficiently defrauded concertgoers under 1341 b/c the concertgoers thought the money was going to charity 1. Reasoning: use of the concert funds was misrepresented, D knowingly participated in the scheme, and intent to deceive one party w/ the purpose of causing financial loss or bringing come financial gain upon oneself iii. Materiality: the fraudulent representation must be material – reasonable man would attach importance to the fact, or the maker of the representation has reason to know its recipient is likely to regard the matter as important in making his decision 1. Lustiger v US: brochure for sale of land which gives a false impression of the land qualifies for liability under 1341 despite the fact that there was not an actual false statement made in the brochure. The brochure was reasonably calculated to defraud e/t a single fact was not misrepresented a. Rationale: the land in question was not able to be inspected by the purchasing parties, so they had to go almost exclusively through the brochure, which was unreasonably “puffed” to give false impressions d. Protected Interests i. US v George: scheme where agent of corp took kickbacks from supplier to maintain business w/ the supplier was a scheme that deprived corp of the agent’s honest services (intangible interest) to negotiate the best price from the supplier 1. Rationale: the intangible interest in this case is information, which agent knew that supplier was willing to pay a higher price for the product, and thus should have informed the corp instead of arranging the kickbacks for himself 2. Problem: under intangible rights model, gov’t need not prove that party actually lost money or property, nor does gov’t need to show that defrauding parties benefited from fraud ii. McNally: Supreme Court strikes down the intangible rights model for mail fraud iii. US v Carpenter: scheme to communicate the contents of a business article to outside parties deprived the WSJ of “property” b/c the story was WSJ’s confidential business information & brokers violated the WSJ’s right to the business information 1. Reasoning: this case comes after McNally, but b/f 1346 is passed, so the court must construe the concept of property broadly to get mail fraud conviction in this case b/c it cant invoke intangible rights model iv. USC 1346: intangible “right to honest services” include w/in definition of property in 1341 1. US v DeVegter: private sector employee violated 1346 honest services provision b/c he owed a fiduciary duty to his employer and should have foreseen harm of contracting an inferior bidder for the work a. Private Sector Employee Test for Violation of 1346: i. Intended breach of fiduciary duty ii. Employee foresaw, or should have reasonably foreseen harm to employer as a cause of the breach b. Public Sector Employee Test for Violation of 1346: i. Illicit personal gain by a public official (public officials owe an inherent fiduciary duty to the public c. Rationale: the court is limiting the scope of private sector rights by requiring a fiduciary duty to impose mail fraud liability v. Sovereign Interests 1. Cleveland v US: states do not have property interest in a regulatory licensing regime a. Rationale: D paid for whatever property interest the license constituted when he acquired the license; state’s right to choose who to license under the regime was an exercise of sovereign power which could be regulated by criminal penalties, not a property interest 2. Pasquantino v US: scheme to smuggle liquor across the border to Canada qualifies for liability because CA taxes are a property right to which that country is entitled. a. Rationale: distinguishable form Cleveland b/c this is taxes, not a regulatory licensing scheme i. Problem: where does this put corporations who give advice to foreign corps on how to avoid certain taxes? b. Extraterritoriality: the court claims the crime is not extraterritorial in nature b/c the offense is complete once the scheme is in place and the wires are used, doesn’t require D to actually cross the border, only intend to i. Problem: this makes Mail Fraud an inchoate crime, and broadens the scope fo the statute significantly and may subject parties to liability b/f they ever obtain property c. Dissent: bulk of sentence was determined by the amount of which D defrauded CA, which was the crime of tax evasion, thus the crime should be punished by CA vi. Use of the Mails 1. Schmuck v US: D commits odometer fraud car sold to dealer dealer sells to private buyer dealer mails in odometer reading to get car titled; odometer fraud was essential to the scheme for defrauding private buyer b/c cars could not continue to be sold to dealers unless the titling was performed, and the titling required use of the mails a. Use of Mails Test for 1341: incidental to an essential part of the scheme b. Rationale: the majority sees this as a continuing scheme, not as an isolated incident, rule doesn’t require D to mail something himself so long as it is reasonably foreseeable that someone will mail something at some point c. Dissent: this is mail AND fraud, not mail fraud. It encroaches on the authority of the states to charge regular fraud themselves 2. US v Sampson: mailing to victims of fraud in order to “lull them into believing the scheme was legitimate” after receipt of payment was enough of a use of the mails b/c it allowed the scheme to continue 3. Takeaways: use of the mails prong is not very demanding on prosecutors b/c it can be easily established vii. Overcriminalization Theme: the jurisdiction is so expansive and the fraud element so broad that the mailing element becomes trivial, and 1341 becomes more of a general fraud provision than a mail fraud provision 1. Problem: a. Discretion: difficult to enforce??? b. Disrespect: class based loss of respect for law, which may result in reduced compliance c. Misallocation: resources are wasted prosecuting less socially harmful activities d. Al Capone Problem: were punishing ppl that are guilty of serious crimes for petty crimes; the gov’t may be casting too wide a net and being lazy in prosecuting ppl for easy to prove crimes instead of crimes that are difficult to prove

IV. Securities Fraud

a. SEA 10(b): prohibits use of “manipulative or deceptive device” in connection with the purchase or sale of securities b. SEC Rule 10(b)-5: the following qualify as “deceptive devices” i. Employ a device scheme or artifice to defraud ii. Make any untrue statement of a material fact or omit any such fact necessary to make the statement not misleading iii. Engage in a transaction, practice or course of business the would operate as a fraud or deceit c. Classic Theory i. Duty to Disclose/Abstain: arises when 1. D owes a fiduciary duty to other buyer/seller 2. D possesses material, non-public information ii. Chiarella v US: D (worker in a printing press that printed takeover bids) did not have duty to disclose material information gained from his position b/c did not owe a fiduciary duty to the sellers of securities; a duty to disclose does not arise merely from the possession of material, nonpublic, information 1. Reasoning: duty to disclose/abstain rule applies only to corp insiders who gain access to material/nonpublic info simply b/c of their position in the corps, unfair in allowing corp insiders to take advantage of that info w/o disclosure 2. Dissent: general rule that party need nod disclose information in an arms-length transaction is not suitable here b/c info was gained through unlawful means; duty isn’t absolutely necessary to establish a violation of the SEC rule d. Misappropriation Theory i. Defined: arises when the information is obtained by a corp “outsider” who owes a duty to the source of the information, not the trading party ii. US v O’Hagan: misappropriation theory satisfies 10(b) and 10-5 requirements for liability b/c 1. 10(b) deceptive device is the confidential information possessed by the corp outsider the use of which is undisclosed to the corp itself; and 2. 10-5 purchase of securities by corp outsider a. Rationale: disclosure in this case by D would nullify liability b/c there would be no deception e. Tipper/Tippee Theory i. Duty of Tippees: tippee assumes a duty to shareholders not to trade on inside information when 1. Tipper has breached his fiduciary duty to shareholders by disclosing information to tippee 2. Tippee knows or should know that there has been a breach ii. Dirks v SEC: Dirks did not violate duty to shareholders b/c tipper was motivated by a desire to expose the fraud, and thus could not have breached 10(b). 1. Rationale: this implies that one way to determine whether the tipper was under a fiduciary duty is to determine whether the insider stands to gain personally from tipping f. Knowing Possession i. US v Teicher: no need to show that inside information was the motivation for trading in question, all that must be shown is that D was in “knowing possession” of the information when the trades were made 1. Rationale: deceptive practice “in connection with” standard in 10(b) is broad; knowing possession is more consistent with disclose or abstain standard than causal connection; simplicity of not have to show specific intentions of D g. Takeaways: parody of information creates questions as to the parties to which we must disclose information; relationships b/w parties change the dynamics of the parody of information principles

V. Bribery

a. USC 201: see p. 77 i. Bribery: corruptly attempting to influence a public official in the performance of official acts by giving the official valuable consideration (quid pro quo for an act/decision) ii. Gratuity: rewarding a public official for the performance of an official act, e/t intent of payor is benign 1. Problem: tension as to what is an illegal payment and what is a legitimate donation supported by right to free speech (i.e. campaign contributions) iii. Parties Punished: 201 punishes both the giving and receipt of bribes and gratuities iv. Official Acts 1. US v Parker: “official acts” encompasses use of governmental computer systems to fraudulently create documents for the benefit of the employee or a third-party because those acts are w/in employees “trust or profit” e/t the employee did not have the authority to carry out the official act a. Rationale: use of gov’t networks are becoming more prevalent, so expansion of the reading of 201 is merited to keep parties from engaging in this sort of behavior 2. US v Arroyo: an official act means an act which is at “any time pending,” thus includes acts which have been completed b/f the bribe is solicited a. Rationale: the quid pro quo can be premised on a falsehood, which is a broad reading of 201 v. Intent 1. Nexus Requirement a. Bribery: requires 2 way intent i. Intent by the bribor to influence ii. Intent by the bribee to act in accordance w/ the condition of the bribe b. Gratuity: only relevant intent is the intent of to bribor i. US v Sun-Diamond Growers: to establish a violation of 201 for receipt/giving of gratuities, gov’t must show a nexus b/w the thing of value and the official act vi. Public Officials 1. US v Dixson: D employees of a contractor to the gov’t were “public officials” for the purposes of bribery statute b/c they had a “degree of official responsibility for carrying out the program/policy” a. Rationale: D’s were quintessentially gov’t employees b/c they had to follow HDCA guidelines in distributing gov’t money, they were funded directly by federal grant, and Congress had adopted this reading of 201 by approving of Levine vii. Cooperating Witnesses 1. US v Ware: the “whoever” language in 201 does not include the gov’t when it offers leniency to witnesses in exchange for testimony because general words in a statute do not include sovereigns unless specifically mentioned a. Rationale: history and absurdity of prosecuting prosecutors lend against adopting D’s reading of the statute; this allows the gov’t to control size of conspiracies b/c the greater the number of conspirators, the more likely one will be caught and could snitch on higher members of the conspiracy b. Problem: we’re essentially giving ppl leniency who might be morally culpable, to punish those who are less culpable and punish them harshly b. USC 666: prohibits payoffs to state and local officials who are part of an agency or government organization that receives more than $10,000 in federal funds in a one year period i. Federal Program Bribery 1. Salinas v US: there need NOT be shown a misappropriation of the federal funds awarded to the agency in question in order to qualify for liability under 666 a. Rationale: “any business transaction” connotes a broad reading should be given to the statute 2. US v DeLaurentis: there must be some connection b/w the federal interest and the bribery at issue, such connection existed when bribery accepted by one officer gave rise to an increase of incidents involving police at a bar which profited from a renewed liquor license when the federal funds were used to increase police patrols on the streets a. Rationale: connection is necessary to support principles of federalism in Constitution 3. Sabri v US: 666 is not constitutionally invalid for not specifying a connection b/w funds and bribe b/c it is authorized under Necessary and Proper Clause and Spending power authorizing Congress to make sure funds are spent for general welfare

VI. Extortion

a. Hobbs Act – USC 1951: whoever obstructs commerce or commodities in commerce through robbery, extortion, etc. i. Extortion under 1951: unlawfully obtaining property from another, with his consent 1. By threat or actual force, violence, fear; or 2. Under color of official right b. Coercive Extortion i. US v Abelis: reputation for violence is enough to fulfill the coercive element of extortion; reputation need not be put forth to victim so long as victim is aware of and afraid of reputation 1. Problem: raises question of how do we measure fear of the victim, objectively or subjectively? Seems like were punishing gangsters for their status as gangsters, not for their conduct ii. Distinction b/w Bribery & Extortion 1. Bribery: payments made to acquire a benefit one is not entitled to 2. Extortion: payments made to avoid being put in a position that is worse than what that person is legally entitled to iii. Rationale: we make bribes and extortion illegal b/c allowing them might reduce the deterrent effect of sanctions 1. US v Capo: scheme to refer job applicants to corp in exchange for payments not extortion b/c victims were not being induced by fear, but were merely trying to improve their economic chances at obtaining work through making the payments a. Preclusion/Diminished Opportunity Requirement: victim must reasonably believe i. D had power to harm victim ii. D would exploit that power to the victims detriment c. Color of Official Right i. US v Evans: public officials need only obtain a payment to which they are not entitled to “induce” payments under color of official right, knowing that the payment was made in return for official acts 1. Rationale: “induced” is not applicable to extortion under color of official right b/c of the disjunctive “or” in the statute; even if “induced” were to apply to public officials, initiation of the payments is not required to induce if committed under color of official right ii. Takeaway: for extortion charge against public official, gov’t need only show official accepted payment to which he was not entitled

VII.Foreign Corrupt Practices Act

a. 78dd-2, 78ff i. Anti-bribery provisions: prohibits bribing officials for purposes of 1. Influencing acts/decisions 2. Inducing foreign officials to do/omit any official duty; or 3. To secure improper advantage a. In order to assist the company making the payment in obtaining or retaining business or directing business to any person 4. Exceptions: payments that are legal in the country, payments that are used to secure routine governmental action (grease exception) b. US v Kay: bribing public officials for avoiding the imposition of certain importation taxes does fall w/in the ambit of FCPA for purposes of obtaining or retaining business b/c such payments can secure an advantage for payor by lowering costs i. Rationale: by enacting FCPA Congress intended to prohibit both bribery leading to discrete contractual arrangements and payments that more generally help payor obtain or retain business c. Theme: models of corruption i. Centralized: kingpin who extorts large payments and distributes them to others ii. Decentralized: every member of the bribe group is able to solicit small payments 1. Most costly model b/c it creates a holdup problem where payments will get more and more expensive the further down the line d. Rationale: prohibiting bribes reduces inefficiencies of American companies by giving them an incentive to invest in production and make products cheaper; also creates a beneficial reputational effect

VIII. False Statements

a. USC 1001: whoever i. In a matter w/in jurisdiction of legislative, executive, or judicial ii. Knowingly/willfully 1. Falsifies/conceals a material fact 2. Makes materially false statements/representations; or 3. Uses a false writing/document to make materially false statements iii. Materiality: does statements have a natural tendency to influence or is it capable of influencing any governmental action/decision (capacity to influence, not actual effect) b. US v Pickett: false statements that trigger an investigation are not w/in scope of 1001; false statements made while there is a concurrent investigation ongoing regarding a separate matter are not w/in scope of 1001 c. Brogan v US: an exculpatory “no” by D when asked if he committed crime qualifies for 1001 liability i. Rationale: false statements need not “pervert governmental function” to qualify for 1001 liability; 5th amend does not sanction lying, only permits silence ii. Problem: this allows investigators to gain leverage by asking straightforward questions of guilt, and then use those violations of 1001 as leverage; D’s may not have knowledge of the repercussions of lying to investigators d. US v Yermian: D does not need to know his false statements will be transmitted to the gov’t, as long as he should have known that his statements would be transmitted to the gov’t e. US v Ramos: 1001 (false statements) and 1542 (lying to secure a passport) are concurrently chargeable and do not violate Blockburger principles i. Rationale: 1001 requires materiality, which 1542 doesn’t; 1542 requires statements be made w/ intent to secure a passport, which 1001 doesn’t

IX. Perjury

a. USC 1621 (Perjury): whoever i. Takes an oath b/f a tribunal, officer or person that he will testify truthfully ii. Willfully states any material matter which he does not believe to be true b. USC 1623 (False Declarations): whoever i. Under oath in any proceeding b/f any US court or grand jury ii. Knowingly makes any false material declarations 1. Perjury v False Declarations a. Perjury applies to a broader range of proceedings b. Perjury statute contains more rigorous proof requirements on falsity c. False declarations provides limited defense of recantation c. Bronston v US: answers under oath that only imply a material matter that one believes not to be true does not qualify as perjury under 1621 i. Rationale: burden should be on questioner to clarify questions so that they are unambiguous; making perjury too broad might have a chilling effect on witness testimony d. Recantation Defense: allowed in 1623 (False Declarations), but not under 1621 (Perjury) i. Rationale: not allowed in perjury b/c witness might hedge his bet by lying, and then coming clean if he thought he was going to be caught ii. Recantation Analysis 1. At time of admission, declaration has not substantially affected proceedings; OR (Court in Sherman reads this as an AND) 2. The falsity has not been exposed a. US v Sherman: charging D w/ 1621 violation and precluding a recantation defense when the gov’t could have charged D w/ 1623 is not a violation of DP b/c falsity had already been exposed and D could thus not invoke the recantation defense i. Rationale: court reads the OR in the statute as an AND b/c the recantation defense would otherwise have the absurd result of allowing D to lie until the lie was about to be discovered, then recant e. US v Stewart: D was not entitled to vacation of judgment b/c of perjured gov’t witness testimony b/c testimony was related to a charge which was dismissed, was nto materially necessary for jury in returning the verdict, aspects of perjured testimony were corroborated by defense expert i. Perjured Testimony and Vacated Conviction: requires 1. Gov’t know of the perjured testimony 2. Reasonable likelihood that testimony affected jury

X. Obstruction of Justice

a. USC 1503: punishes anyone who endeavors to do any of the following to a juror/official i. Injures ii. Influences, obstructs or impedes; or iii. Endeavors to influence, obstruct or impede the due administration of justice (omnibus clause) 1. “Endeavor” avoids attempt law by punishing any attempt to do what the statute forbids so long as it has a reasonable tendency to corrupt the proceeding b. Rationale: twin rationales of obstruction of justice statutes i. Protect participation in judicial and administrative proceedings from the use of force, intimidation, or corrupt means of influence ii. Preserves the integrity of the judicial and administrative decision-making process c. USC 1505: corrupt endeavor to obstruct agency or congressional proceedings d. USC 1512: i. Corrupt persuasion to induce another to withhold, destroy or alter evidence ii. Corruptly destroying or altering evidence or otherwise obstructing official proceeding iii. Harassing another to prevent attendance or testimony at an official proceeding or reporting of crime to federal authorities e. USC 1513: retaliating against informant for providing information f. USC 1519: knowingly destroying or altering evidence w/ intent to impede investigation or proceeding g. USC 1520: knowingly and willfully destroying corporate audit records h. US v Simmons: grand jury investigation was “pending” for purposes of 1503 b/c subpoenas had been issued i. Rationale: obstruction of justice n/a to investigations by federal authorities unless a grand jury has convened b/c investigations are not “administrations of justice” i. US v Griffin: perjurious conduct violates obstruction laws just as much as evasive answers do i. Rationale: despite the fact that the federal system punishes perjury separately and is equipped to uncover perjury through cross examination j. US v Aguilar: no obstruction w/ false statements b/c D did not know his statements would be used in a grand jury investigation i. Rationale: D knew a grand jury was being convened, but intent requires a nexus false statements and their use at the proceedings; no evidence that the natural and probable effect of D’s statements would be use in front of a grand jury k. US v Lester: 1503 omnibus clause still applicable to witnesses after addition of 1512 (witness tampering prohibition) tampering b/c it did not eliminate the second objective for prohibiting obstructions of justice, which is preventing miscarriages of justice through corrupt means i. Rationale: 1512 only punishes coercive witness tampering, but not non-coercive witness tampering. 1503 omnibus serves purpose of continuing to cover non-coercive witness tampering l. Arthur Andersen v US: knowingly corruptly persuading under 1512 requires knowledge that the object of the persuasion is unlawful i. Rationale: “knowing persuasion” w/o element of corruptness would encompass lawful activity and could not be what the statute was meant to prohibit m. US v Wilson: harassment standard i. Harassment = justifiable reaction to threatening statements, not repeated attacks ii. Endeavoring to dissuade attaches e/t the endeavor may have no actual effect iii. Witness status continues until adjournment of trial, so harassment of witness that had already testified while trail was still in session qualifies under the statute

XI. Drug Crimes a. USC 841: is is unlawful for a person to knowingly or intentionally i. Manufacture, distribute, possess w/ intent to do any of the preceding, or ii. To do the same w/ a counterfeit substance b. USC 844: unlawful for a person to knowingly possess a controlled substance i. US v Chapman: congress intended to include the blotter paper on which LSD was absorbed in the definition of “mixture/substance” in 841 1. Rationale: no DP violation b/c Congress has rational basis for including blotter paper, it wanted to punish street dealers who mixed the substance more harshly; problem arises b/c LSD is generally measured by does, not weight ii. Posner Dissent: this is an illogical result b/c is results in disparity, in contrary to the goals of the sentencing guidelines, given the same dose of LSD in different weight mixtures, and also in the way LSD is treated in comparison to other drugs 1. Takeaway: this is a classic Textualist (Rehnquist) v Functionalist (Posner) debate on how judges should interpret the laws c. US v Smith: vagueness is not grounds for attacking sentencing guidelines 100:1 ratio of crack v powder cocaine b/c guidelines are not law and thus not susceptible to such attacks d. Career Criminal Enterprise i. US v Richardson: jury must find each violation in the series of violations charged w/ unanimity when convicting under CCE, rather than just agree that a general series of violations had occurred 1. Rationale: “violation” connotes that the jury must find conduct violated the law, and thus must do so unanimously; allowing the jury to agree merely that a series of violations occurred is too close to allowing the jury to convict on reputation and not conduct 2. Takeaway: this decision made the CCE requirements of 5 person involvement, substantial income from crimes, and series of violations too hard to prove, and thus led to more use of the RICO statute to prosecute these sorts of offenders

XII.Racketeer and Corrupt Influenced Organization

a. USC 1961: definitions i. Racketeering Activity: see statute p 116 ii. Enterprise: individual, partnership, corporation, association, or other legal entity, and any union or group of individuals associated in fact although not a legal entity iii. Pattern of Racketeering Activity: two acts of racketeering activity w/in ten years of each other b. USC 1962: prohibits i. Investing in an enterprise if the investor has acquired funds from a pattern of racketeering activity ii. Using a pattern of racketeering to acquire an interest in or maintain control over an enterprise iii. Conducting the affairs of an enterprise through a pattern of racketeering activity iv. Conspiring to do i-iii c. Theme: unclear what a “racketeer” is b/c statute does not define, only defines “pattern of racketeering activity” d. Enterprise i. Defined: requires proof of 1. Common purpose 2. Continuity 3. Structure ii. US v Turkette: violation of the statute requires proof of both an “enterprise” and a “pattern of racketeering activity;” definition of enterprise includes both legitimate and illegitimate enterprises 1. Rationale: language of RICO should be liberally construed to effect its purposes iii. NOW v Scheidler: enterprise under RICO need not have an economic motive or own a property interest in the enterprise to violate provision 1. Rationale: “affect commerce” in statute does not necessarily connote economic motive, e/t D’s might not benefit personally from abortion clinic protests, such protests hinder the economy e. Pattern of Racketeering Activity i. HJ Inc v Northwestern Bell: proof of a “pattern of racketeering” requires continuity + relationship 1. Continuity: can be shown by evidence that suggests a long-term threat, regular way of doing business, or in other ways (series, multiple schemes not enough to show continuity) a. Closed continuity: past repeated acts which occurred w/in a period of time b. Open Continuity: conduct that poses a threat for criminal activity in the future 2. Relationship: acts having similar purpose, result, participants, victims, methods of commission, or otherwise interrelated and not isolated events (showing more than one predicate offense not enough to establish relationship) f. State Predicate Crimes i. US v Garner: “bribery” predicate offense proscribed by RICO included gratuities prohibited by state law 1. Rationale: test for whether the charged acts for the generic predicate offense is whether the indictment charges a type of activity generally characterized in the proscribed category; unlawful gratuity is an attack on the integrity of a public official in the same way that bribery is 2. Takeaway: this is an expansion of RICO to influence the public operation of facilities, in contrast to its original purpose of trying to eliminate racketeers g. Relationship b/w Person & Enterprise i. Reves v Ernst & Young: “conduct/participate” in 1962(c) means to have some sort of management/control, not merely be involved in the enterprise affairs 1. Rationale: “conduct” connotes an element of control, and “participate” connotes that mere involvement is not enough h. Conspiracy i. Salinas v US: it was enough to violate RICO conspiracy provision that D knew of the predicate offenses and agreed to facilitate their commission 1. Rationale: RICO conspiracy statute is a broadening of traditional conspiracy prohibitions b/c it eliminates overt act requirement, which indicates that the statute should not be read narrowly; general conspiracy allows conspirators to be convicted as long as they facilitate the commission of the crime, they need not “agree” i. Asset Forfeiture i. USC 1963: requires forfeiture of any interest D has acquired or maintained through the RICO violation, any interest in the enterprise, and any contractual right that afforded D influence over the enterprise involved in the RICO violation 1. US v Simmons: a. D convicted of involvement in a scheme that was part of a larger criminal enterprise was jointly and severally liable for proceeds gained from the entire criminal enterprise despite his lack of participation in the specific scheme found to violate RICO i. Rationale: members of a conspiracy are responsible for the foreseeable acts of their coconspirators b. “Proceeds” under asset forfeiture provision constitute “gross receipts” of illegal activity, and there can be no “net” deduction for the expenses incurred in the criminal acts 2. US v Rubin: union official could be forced to forfeit office as union official b/c such office is “contractual right” as defined by 1963, but official cannot be forced to forfeit office in perpetuity a. Rationale: future right to run for office is not a contractual right, statute does not prohibit reacquisition of interests forfeited ii. Third-Party Interests 1. Requirements to Claim a Third-Party Interest in Forfeited Assets under RICO a. 1963(L)(6)(A): right to forfeiture invalid if title to assets is superior in P at time of commission of the acts that gave rise to forfeiture b. 1963(L)(6)(B): purchaser of asset was at time of purchase reasonably w/o cause to believe the property was subject to forfeiture 2. US v BCCI: creditor bank cannot exercise rights to set off amount due from loan granted to D b/f turning assets over to gov’t b/c it did not exercise its right to set off until after the alleged offenses & and high publicized nature of the offense means that bank should have reasonably known of the commission of the offenses b/f it issued the loan iii. Attorney’s Fees 1. Caplin & Drysdale v US: forfeited funds vest in the gov’t at the moment of the commission of the acts, & D has no 6th amend right to use another’s funds to obtain preferred counsel a. Rationale: D can use non-forfeited funds to obtain counsel, or get attorneys to work on contingency and collect from forfeited funds if D is acquitted b. Dissent: this allows the gov’t to beggar D b/f trial j. Civil Liability i. Generally: civil RICO allows for collection of treble damages & attorneys fees, as well as injunctive relief; P must prove all elements of the RICO violation and show that he suffered injury b/c of the violations ii. Sedima v Imrex: civil liability doesn’t require a previous criminal conviction for violation of RICO, nor does it require a “racketeering injury” separate from the commission of the predicate offenses 1. Rationale: statute allows civil liability for conduct “punishable/indictable” by RICO, not “conviction;” keeps w/ Congress’s intent of increasing enforcement of RICO provisions by allowing civil enforcement (private attorney generals) k. Injury to Plaintiff i. Standing 1. Standing to Bring a Claim for Civil RICO Violations Requires a. Injury in fact – invasion of legally protected interest which is i. Concrete/particularized ii. Actual/imminent b. Causation c. Redressability 2. Libertad v Welch: women seeking abortion at clinics, and pro-abortion groups, did not suffer injury b/c of anti-abortion group protests b/c intimidation doesn’t qualify as injury and pro-abortion group’s could still achieve their organization’s goals. Doctors & owners of abortion clinics, however, did suffer injury to property from damage proximately caused by protesters & could have those injuries redressed by injunctive relief sought ii. Causation 1. Anza v Ideal Steel: D who illegally failed to charge taxes on cash transactions did not proximately cause the loss of business to P b/c there was no direct relation, the party who was proximately harmed by the failure to charge tax was the state a. Rationale: D could have lowered its prices for other reasons besides the fraudulent practices, lost sales by P could be do to something other than lower prices, uncertainty in calculation of damages, State is in better position to bring a RICO claim than P l. Takeaway: RICO in this context is being used as a sort of super-tort statute that is extremely broad and awards treble damages which creates lots of motivation to litigate; the court is trying to narrow the civil use of the statute by drawing bright-line rules as in the standing and causation cases

XIII. Currency Reporting & Money Laundering

a. Currency Reporting Requirements i. 26 USC 6050I 1. any person engaged in a business who receives more than 10,000 in cash in one transaction (or two or more related transactions) must report money in the manner prescribed by the Secretary of Treasury 2. anti structuring provision ii. USC 5313: report required when domestic financial institution is involved in a transaction of united states coins/currency iii. USC 5314: recording requirement when domestic citizen makes transactions w/ foreign financial agency iv. USC 5316: person exporting/importing $10,000+ must submit a report to the Secretary of Treasury 1. US v $47,980: knowledge of the reporting requirement need not be proved by gov’t in civil forfeiture proceeding in rem for violation of the currency reporting requirements 2. US v Bajakajian: where money was proceeds of legal activity and non-reporting worked little social harm, forfeiture of entire $347,000 violated 8th amend prohibition on excessive fines b/c it was grossly disproportionate to the gravity of the offense a. Rationale: forfeiture is equivalent to a fine b/c it is a financial penalty for unlawful activity, thus the case falls under the 8th amend b. Dissent: this is not a fine b/c the money is an instrumentality of the crime; D also lied at various points in the investigation indicating that the money was a product of illegal activity v. USC 5322: “willful” violation of the preceding statute required to convict 1. Ratzlaf v US: “willful” violation of that statute requires that D know that structuring is unlawful in order to convict a. Rationale: though mistake of law is generally not a defense, Congress structured this provision to allow it; structuring is not the sort of thing that the average person would intuitively associate w/ illegal activity b. Dissent: structuring transactions indicates knowledge of the bank’s reporting requirement, and thus indicates knowledge of the law to some extent and should foreclose a mistake of law defense b. Money Laundering Prohibitions i. USC 1956: 1. D conducts or attempts to conduct a financial transaction 2. Property involved in the transaction is product of a felony 3. D knew transaction involved proceeds from a felony 4. Committed the violation for the purpose of a. Promotion of unlawful activity b. Commission of tax fraud/evasion c. Concealment of the source of proceeds d. Avoidance of the currency reporting requirement i. US v Campbell: under the table cash transaction qualifies for “concealment of funds;” willful blindness creates a presumption of knowledge that funds were proceeds of illegal activity where realtor deliberately ignored signs that funds used to buy house were proceeds from unlawful drug activity 1. Rationale: evidence that D drove a Porsche, carried a cell-phone, had large amounts of cash, and didn’t work during normal business hours should indicate that proceeds were drug money ii. USC 1957: 1. D engaged or attempted to engage in a monetary transaction 2. In criminally derived property of value greater than $10,000 3. Knowing the property was derived from unlawful activity 4. The property was in fact derived from the “specified unlawful activity” a. US v Johnson: i. D’s purchase of a house w/ proceeds from a felony was “promotion” under 1956 of the unlawful activity b/c it was used to persuade victims of a peso scheme that D’s money was derived from legitimate sources ii. Wiring of funds to D who was charged w/ wire fraud were not “criminally derived property” under 1957 b/c the wire fraud did not occur until after the funds were deposited into D’s account iii. Enough evidence to show that funds wired back to investors in peso scheme as “profits” were criminally derived property where only 1.2% of funds were not determined to be from illegal activity 1. Rationale: gov’t need not show that no “untainted” funds were used in the offense to prove funds were criminally derived

XIV. Corporate Criminal Liability

a. NY Central & Hudson River RR v US: public policy supports holding corps liable for knowledge and intent of their agents in the commission of illegal acts from which the corp profits i. Rationale: serves as useful in controlling abuses of law by the corp from become payments of license b. US v Bard: plea agreement of company charged w/ intentionally hiding information from FDA found reasonable i. Rationale 1. Individual employees are being prosecuted separately 2. Corp cooperated w/ gov’t 3. Corp fined amount equal to profits gained from illegal activity 4. Reorganization requirement part of plea agreement to prevent future violations c. Respondeat Superior Rule i. Commonwealth v Beneficial Finance: proper test for corporate liability b/c of the acts of an agent is whether or not the agent was acting w/in the scope of his employment; scope of employment determined by whether or not the agent was acting on behalf of the corp in relation to the duties that individual is authorized to perform 1. Rationale: competing MPC standard creates too high a standard of proof on the prosecution; reflects theory that most action of corps that leads to criminal liability is being carried out by lower echelon employees ii. People v Lessof Berger: partnerships qualify for corporate liability, and partners who are uninvolved in criminal activity may be indicted for the actions of offending partner 1. Rationale: partnership law holds partners jointly and severally liable for the actions of other partners b/c ALL partners profit from illegal activity of another iii. US v Hilton Hotels: Sherman Act liability attaches to corp for the acts of its agents w/in scope of employment e/t acts were contrary to express instruction to agent and corp policy 1. Rationale: high corp officials are presumed to know of Sherman Act violations b/c they have the goal of maximizing profits from which the corp receives the benefit d. MPC Rule i. US v Bank of NE: corp is presumed to have knowledge when 1. Corp consciously avoids learning about the violation (willful blindness) 2. Corp has agent who possessed the requisite knowledge to commit the offense (respondeat superior) 3. Corp has several employees w/ knowledge which, when aggregated, qualifies for the requisite knowledge to violate the statute (collective knowledge) a. Rationale: keeps corps from fragmenting information or departments to avoid criminal liability ii. State v Chapman Dodge: car dealership that had no knowledge of the abuses of lower level employees b/c purchase of subsidiary not liable for subsidiary employee offenses 1. Rationale: BOD did not specifically authorize actions in question, and had no knowledge of the offenses otherwise b/c lower level employees made the decisions iii. EF Hutton: settlement of criminal indictment often leads to much worse penalties than those inflicted by the gov’t, such as SEC & local gov’t investigations, & private sanctions b/c of loss of business

XV.Personal Liability in an Organizational Setting

a. US v Wise: a corp officer is subject to personal liability for his actions on behalf of the corp whenever he knowingly participates in perpetrating the offense regardless of whether he is acting in a representative capacity i. Rationale: if personal liability did not attach, fines imposed by Congress for violation of corp laws would amount to license fees for illegitimate activity; social stigma of criminal liability meant to add to deterrent effect b. Personal Liability for Omissions by Corporate Officers i. US v Dotterweich: personal liability attaches to corp officer for omission of duty under FDA act violation for shipping misbranded items e/t officer did not know items were misbranded or take part in shipping them 1. Rationale: D stood in “responsible relation” to a public danger e/t he was otherwise innocent; this type of liability arises mostly in the context of public welfare offenses ii. US v Park: D could be held personally liable for failure of corp to correct violations of FDCA e/t D himself was not guilty of any “wrongful action;” it sufficed that D was in a position to be deemed personally responsible 1. Rationale: Dotterweich aims to put burden on corp directors to seek out and remedy violations when they occur & duty to implement measure to avoid recurrence of violations; D’s have available to them a “powerlessness” defense so that when compliance is impossible personal liability does not apply; this amounts to strict liability c. US v Jorgensen: D’s found to have intent to violate FMIA b/c they knew of the misbranding carried-out by colleagues & were in a responsible relationship w/in the company regarding the misbranding of the meat i. Rationale: this is not strict liability as was imposed in park; there was intent requirement in FIMA

XVI. Deferred Prosecution Agreements

a. Stolt-Nielsen v US: gov’t had absolute right to indict D for violation of deferred prosecution agreement b/c indictment is not a “constitutional right” that will be “chilled” as if it were a conviction i. Reasoning: no constitutional right not to be indicted; D can claim agreement as a defense at trial 1. Antitrust Corp Leniency Policy: gov’t agrees not to charge a firm criminally for the activity being reported if a. Applicant is first to report illegal activity b. Gov’t does not, at time applicant comes forward, have enough information to sustain a conviction c. The applicant took prompt effective action to terminate its part in the activity d. Report is made w/ candor and completeness and provides full cooperation e. Applicant confesses to corporate responsibility for violations f. Applicant makes restitution g. Granting leniency would not be unfair b. Fines & Indemnification: organizations generally pay employee legal fees when the corp employees come under investigation for acts on behalf of the corp; DE law requires i. Employee act in good faith ii. In the corps best interest iii. Had no reason to believe the conduct was unlawful 1. US v Stein:

XVII. Sanctions

a. Bergman b. Browder c. Booker