**********Iltig*MIO******************************************** * Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Scan Made * * from the Original Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nudge, Ahoribuzz and @Peace

GROOVe gUiDe . FamilY owneD and operateD since jUlY 2011 SHIT WORTH DOING tthhee nnuuddggee pie-eyed anika moa cut off your hands adds to our swear jar no longer on shaky ground 7 - 13 sept 2011 . NZ’s origiNal FREE WEEKlY STREET PRESS . ISSUe 380 . GROOVEGUiDe.Co.NZ Untitled-1 1 26/08/11 8:35 AM Going Global GG Full Page_Layout 1 23/08/11 4:00 PM Page 1 INDEPENDENT MUSIC NEW ZEALAND, THE NEW ZEALAND MUSIC COMMISSION AND MUSIC MANAGERS FORUM NZ PRESENT GOING MUSIC GLOBAL SUMMIT WHAT YOU NEED TO KNOW BEFORE YOU GO If you are looking to take your music overseas, come and hear from people who are working with both new and established artists on the global stage. DELEGATES APPEARING: Natalie Judge (UK) - Matador Records UK Adam Lewis (USA) - The Planetary Group, Boston Jen Long (UK) - BBC6 New Music DJ/Programmer Graham Ashton (AUS) - Footstomp /BigSound Paul Hanly (USA) - Frenchkiss Records USA Will Larnach-Jones (AUS) - Parallel Management Dick Huey (USA) - Toolshed AUCKLAND: MONDAY 12th SEPTEMBER FREE ENTRY SEMINARS, NOON-4PM: BUSINESS LOUNGE, THE CLOUD, QUEENS WHARF RSVP ESSENTIAL TO [email protected] LIVE MUSIC SHOWCASE, 6PM-10:30PM: SHED10, QUEENS WHARF FEATURING: COLLAPSING CITIES / THE SAMI SISTERS / ZOWIE / THE VIETNAM WAR / GHOST WAVE / BANG BANG ECHE! / THE STEREO BUS / SETH HAAPU / THE TRANSISTORS / COMPUTERS WANT ME DEAD WELLINGTON: WEDNESDAY 14th SEPTEMBER FREE ENTRY SEMINARS, NOON-5PM: WHAREWAKA, WELLINGTON WATERFRONT RSVP ESSENTIAL TO [email protected] LIVE MUSIC SHOWCASE, 6PM-10:30PM: SAN FRANCISCO BATH HOUSE FEATURING: BEASTWARS / CAIRO KNIFE FIGHT / GLASS VAULTS / IVA LAMKUM / THE EVERSONS / FAMILY CACTUS PART OF THE REAL NEW ZEALAND FESTIVAL www.realnzfestival.com shit Worth announciNg Breaking news Announcements Hello Sailor will be inducted into the New Zealand Music Hall of Fame at the APRA Silver Scroll golDie locks iN NZ Awards, which are taking place at the Auckland Town Hall on the 13th Dates September 2011. -

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data As a Visual Representation of Self

MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Design University of Washington 2016 Committee: Kristine Matthews Karen Cheng Linda Norlen Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Art ©Copyright 2016 Chad Philip Hall University of Washington Abstract MUSIC NOTES: Exploring Music Listening Data as a Visual Representation of Self Chad Philip Hall Co-Chairs of the Supervisory Committee: Kristine Matthews, Associate Professor + Chair Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Karen Cheng, Professor Division of Design, Visual Communication Design School of Art + Art History + Design Shelves of vinyl records and cassette tapes spark thoughts and mem ories at a quick glance. In the shift to digital formats, we lost physical artifacts but gained data as a rich, but often hidden artifact of our music listening. This project tracked and visualized the music listening habits of eight people over 30 days to explore how this data can serve as a visual representation of self and present new opportunities for reflection. 1 exploring music listening data as MUSIC NOTES a visual representation of self CHAD PHILIP HALL 2 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF: master of design university of washington 2016 COMMITTEE: kristine matthews karen cheng linda norlen PROGRAM AUTHORIZED TO OFFER DEGREE: school of art + art history + design, division -

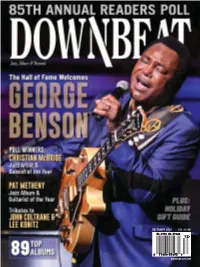

Downbeat.Com December 2020 U.K. £6.99

DECEMBER 2020 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM DECEMBER 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 12 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Block Remembered for Fierce Dedication to OWU

Got secrets? Accio Pottermore!: OWU PostSecret cards hit OWUWarts just doesn’t HamWill Thursday sound as cool... -- Page 2 -- Page 3 THE OLDEST CONTINUALLY PUBLISHED STUDENT NEWSPAPER THE TranscripT IN THE COUNTRY Thursday, Oct. 20, 2011 Volume 149, No. 6 WoHo and HelpLine team Block remembered for fierce dedication to OWU up to educate By Kathleen Dalton a member of the OWU class of politics and government, ten by students on the impact campus about Transcript Reporter of 2014 and Lugg works as a spoke of not only her profes- Block had on their lives. The writing tutor in the Sagan Aca- sional relationship with Block reflections focused not only sexual assault Lydia Block was remem- demic Resource center. but also of their personal rela- on the ways in which Block bered for her passion and de- Block-Wilkins and Lugg lit tionship and the strength and helped students academically By Eric Tifft votion for her job, family and the Yizkor Memorial Candle ease of their friendship. and with their chosen ca- Transcript Reporter the home she found at Ohio during the ceremony as part of “She was fierce, fierce about reer paths but also the ways Wesleyan University during the Yom Kippur observance. programs and people she cared in which Block developed Sexual assault is a vola- the Oct. 7 memorial celebra- The Kappa Alpha Theta about, and she was sassy, very friendships with the students tile, and many times emo- tion devoted to her life. (Theta) sorority, of which sassy,” said McLean. she worked with. tional, topic on college cam- Block died in June after Block-Wilkins is a member, This description of Block “Dr. -

Triple J Hottest 100 2011 | Voting Lists | Sorted by Artist Name Page 1 VOTING OPENS December 14 2011 | Triplej.Net.Au

360 - Boys Like You {Ft. Gossling} Anna Lunoe & Wax Motif - Love Ting 360 - Child Antlers, The - I Don't Want Love 360 - Falling & Flying Architecture In Helsinki - Break My Stride {Like A Version} 360 - I'm OK Architecture In Helsinki - Contact High 360 - Killer Architecture In Helsinki - Denial Style 360 - Meant To Do Architecture In Helsinki - Desert Island 360 - Throw It Away {Ft. Josh Pyke} Architecture In Helsinki - Escapee [Me] - Naked Architecture In Helsinki - I Know Deep Down 2 Bears, The - Work Architecture In Helsinki - Sleep Talkin' 2 Bears, The - Bear Hug Architecture In Helsinki - W.O.W. A.A. Bondy - The Heart Is Willing Architecture In Helsinki - Yr Go To Abbe May - Design Desire Arctic Monkeys - Black Treacle Abbe May - Taurus Chorus Arctic Monkeys - Don't Sit Down Cause I've Moved Your About Group - You're No Good Chair Active Child - Hanging On Arctic Monkeys - Library Pictures Adalita - Burning Up {Like A Version} Arctic Monkeys - She's Thunderstorms Adalita - Hot Air Arctic Monkeys - The Hellcat Spangled Shalalala Adalita - The Repairer Argentina - Bad Kids Adrian Lux - Boy {Ft. Rebecca & Fiona} Art Brut - Lost Weekend Adults, The - Nothing To Lose Art Vs Science - A.I.M. Fire! Afrojack & Steve Aoki - No Beef {Ft. Miss Palmer} Art Vs Science - Bumblebee Agnes Obel - Riverside Art Vs Science - Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger {Like A Albert Salt - Fear & Loathing Version} Aleks And The Ramps - Middle Aged Unicorn On Beach With Art Vs Science - Higher Sunset Art Vs Science - Meteor (I Feel Fine) Alex Burnett - Shivers {Straight To You: triple j's tribute To Art Vs Science - New World Order Nick Cave} Art Vs Science - Rain Dance Alex Metric - End Of The World {Ft. -

Earcandyeofs 11 68 Songs, 4.3 Hours, 642.3 MB

EarCandyEofS 11 68 songs, 4.3 hours, 642.3 MB Name Time Album Artist Alive 3:54 EarCandy End of Summer 2011 Armand Margjeka Lose It (Young Galaxy Remix) 4:16 EarCandy End of Summer 2011 Austra Shufe 3:55 EarCandy End of Summer 2011 Bombay Bicycle Club Just Ride It 3:36 EarCandy End of Summer 2011 Cuckoo Chaos All It Takes 3:24 EarCandy End of Summer 2011 Cut Of Your Hands o m a m o r i 4:19 EarCandy End of Summer 2011 elite gymnastics Dreams To Wishes 4:13 EarCandy End of Summer 2011 Fabian Wild Window 2:57 EarCandy End of Summer 2011 Fool's Gold Top Bunk 4:44 EarCandy End of Summer 2011 Gauntlet Hair 252 5:30 EarCandy End of Summer 2011 Gem Club The Town Crazies 2:49 EarCandy End of Summer 2011 Hypocrite in a Hippy crypt Everything to me 3:07 EarCandy End of Summer 2011 LIPS Songs Midnight City 4:03 EarCandy End of Summer 2011 M83 I Can Hear The Trains Coming 2:36 EarCandy End of Summer 2011 Mathieu Santos The Bay (Clock Opera Remix) 4:38 EarCandy End of Summer 2011 Metronomy Bronx Sniper 3:39 EarCandy End of Summer 2011 Mister Heavenly Fallout 3:37 EarCandy End of Summer 2011 Neon Indian Safe Living 3:40 EarCandy End of Summer 2011 Pina Chulada Untitled 4:24 EarCandy End of Summer 2011 POMPEYA A Dream I Had 3:44 EarCandy End of Summer 2011 Porcelain Raft Sleep Forever 6:19 EarCandy End of Summer 2011 Portugal. -

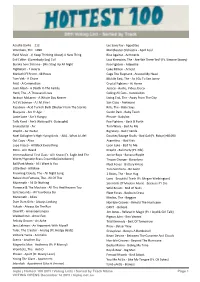

Triple J Hottest 100 2011 | Voting Lists | Sorted by Track Name Page 1 VOTING OPENS December 14 2011 | Triplej.Net.Au

Azealia Banks - 212 Les Savy Fav - Appetites Wombats, The - 1996 Manchester Orchestra - April Fool Field Music - (I Keep Thinking About) A New Thing Rise Against - Architects Evil Eddie - (Somebody Say) Evil Last Kinection, The - Are We There Yet? {Ft. Simone Stacey} Buraka Som Sistema - (We Stay) Up All Night Foo Fighters - Arlandria Digitalism - 2 Hearts Luke Million - Arnold Mariachi El Bronx - 48 Roses Cage The Elephant - Around My Head Tom Vek - A Chore Middle East, The - As I Go To See Janey Feist - A Commotion Crystal Fighters - At Home Juan Alban - A Death In The Family Justice - Audio, Video, Disco Herd, The - A Thousand Lives Calling All Cars - Autobiotics Jackson McLaren - A Whole Day Nearer Living End, The - Away From The City Art Vs Science - A.I.M. Fire! San Cisco - Awkward Kasabian - Acid Turkish Bath (Shelter From The Storm) Kills, The - Baby Says Bluejuice - Act Yr Age Caitlin Park - Baby Teeth Lanie Lane - Ain't Hungry Phrase - Babylon Talib Kweli - Ain't Waiting {Ft. Outasight} Foo Fighters - Back & Forth Snakadaktal - Air Tom Waits - Bad As Me Drapht - Air Guitar Big Scary - Bad Friends Noel Gallagher's High Flying Birds - AKA…What A Life! Douster/Savage Skulls - Bad Gal {Ft. Robyn}+B1090 Cut Copy - Alisa Argentina - Bad Kids Lupe Fiasco - All Black Everything Loon Lake - Bad To Me Mitzi - All I Heard Drapht - Bali Party {Ft. Nfa} Intermashional First Class - All I Know {Ft. Eagle And The Junior Boys - Banana Ripple Worm/Hypnotic Brass Ensemble/Juiceboxxx} Tinpan Orange - Barcelona Ball Park Music - All I Want Is You Fleet Foxes - Battery Kinzie Little Red - All Mine Tara Simmons - Be Gone Frowning Clouds, The - All Night Long 2 Bears, The - Bear Hug Naked And Famous, The - All Of This Lanu - Beautiful Trash {Ft. -

A Knickerbocker Tour of New York State, 1822: "Our Travels, Statistical

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Electronic Texts in American Studies Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln 1822 A Knickerbocker tour of New York State, 1822: "Our Travels, Statistical, Geographical, Mineorological, Geological, Historical, Political and Quizzical"; Written by Myself XYZ etc. Johnston Verplanck New York American Louis Leonard Tucker , editor The New York State Library Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/etas Part of the American Studies Commons Verplanck, Johnston and Tucker, Louis Leonard , editor, "A Knickerbocker tour of New York State, 1822: "Our Travels, Statistical, Geographical, Mineorological, Geological, Historical, Political and Quizzical"; Written by Myself XYZ etc." (1822). Electronic Texts in American Studies. 61. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/etas/61 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Libraries at University of Nebraska-Lincoln at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Texts in American Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. I iC 1\ N A D I I I 0 iI I' I ~ I A Knickerbocker tour of New York State, 1822 ~~Our Travels, Statistical, Geographical, Mineorological, Geological, Historical, Political and "Quizzical" Written by myself XYZ etc. Edited, with an Introduction and Notes, By LoUIS LEONARD TUCKER The University of the State of New York The State Education Department The New York State Library Albany 1968 THE UNIVERSITY OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK Regents of the University (with years when terms expire) 1969 JOSEPH W. MCGOVERN, A.B., LL.B., L.H.D., LL.D., Chancellor · New York 1970 EVERETT J. -

BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected]

Country Update BILLBOARD.COM/NEWSLETTERS SEPTEMBER 16, 2019 | PAGE 1 OF 20 INSIDE BILLBOARD COUNTRY UPDATE [email protected] Blanco, Highwomen Is The Party Over? Country Gets Score Wins >page 4 Serious With A New Wave Of Singles Conley, Americana And Music Cycles The first time Craig Morgan sang “The Father, My Son and the a child in a dangerous world; and two songs that face mortality, >page 10 Holy Ghost” was also supposed to be the last time. Chris Young’s “Drowning” and Luke Combs’ “Even Though The song details Morgan’s difficult emotional journey I’m Leaving.” following the death of son Jerry Greer, 19, in a 2016 drowning They’re not the only examples. Justin Moore topped the accident, and it left much of the Grand Ole Opry audience in Country Airplay chart on Sept. 7 with “The Ones That Didn’t Church, Aldean tears in March 2019. Backstage, Morgan told Ricky Skaggs he Make It Back Home,” a song about soldiers who died in battle, Go To College doubted he was strong enough to perform it again. accompanied by a video that incorporates first responders >page 11 Skaggs “put his hands on and school shootings. Riley my shoulder with big tears in Green’s new “I Wish Grandpas his eyes,” recalls Morgan. “He Never Died” laments the deaths said, ‘You have to sing that of people and pets, as well as the Garth, Trisha Play song. The world needs to hear decline of the family farm. Tenille Musicians Hall Event this kind of music.’ ” Townes’ “Jersey on the Wall (I’m >page 11 Morgan relented. -

Chapter 4—Environmental Consequences

Chapter 4—Environmental Consequences Giant Sequoia National Monument, Final Environmental Impact Statement Volume 1 377 Chapter 4—Environmental Consequences Volume 1 Giant Sequoia National Monument, Final Environmental Impact Statement 378 Chapter 4—Environmental Consequences Chapter 4 includes the environmental effects analysis. ● Activities would only be conducted after It is organized by resource area, in the same manner appropriate project-level NEPA analysis, if as Chapter 3. Effects are displayed for separate required. resource areas in terms of the ongoing, indirect, and ● Reasonably foreseeable actions do not follow cumulative effects associated with the six alternatives the management direction proposed in the action considered in detail. Effects can be neutral, alternatives. beneficial, or adverse. This chapter also discusses the unavoidable adverse effects, the relationship The following types of actions should be considered between short-term uses and long-term productivity, (depending on resource area): and any irreversible and irretrievable commitments of resources. Environmental consequences form the ● Annual maintenance activities in the scientific and analytical basis for comparison of the Monument, such as roads, trails, special use alternatives. permits, and administrative and recreation sites. These are the activities necessary to maintain basic compliance with regulation and annual operating Types of Effects plans. The Giant Sequoia National Monument Plan is a ● Fuels management in the Monument, such as programmatic plan that defines and describes the prescribed fire and managed wildfire, pile burning, management direction for the Monument for the next maintenance of WUIs (including mechanical 10 to 15 years. Programmatic plans are consistent treatments), and additional fuels reduction with national direction and are, by nature, strategic activities as a result of other vegetation or site and make no site-specific project decisions. -

The Ithacan, 2009-04-30

Ithaca College Digital Commons @ IC The thI acan, 2008-09 The thI acan: 2000/01 to 2009/2010 4-30-2009 The thI acan, 2009-04-30 Ithaca College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_2008-09 Recommended Citation Ithaca College, "The thI acan, 2009-04-30" (2009). The Ithacan, 2008-09. 23. http://digitalcommons.ithaca.edu/ithacan_2008-09/23 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the The thI acan: 2000/01 to 2009/2010 at Digital Commons @ IC. It has been accepted for inclusion in The thI acan, 2008-09 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ IC. OPINION STUDENTS SHOULD HAVE MORE INPUT, PAGE 12 BACK TO THE DIAMOND ACCENT PROFESSORS STRESS FASHION AND STYLE, PAGE 15 Senior infi elder returns for fi nal season, page 27 PHOTO FINISH BLUE AND GOLD TOP HARTWICK, PAGE 32 Thursday Ithaca, N.Y. April 30, 2009 The Ithacan Volume 76, Issue 28 College gathers Hidden in the to remember life promisedland of active student BY ELIZABETH SILE Migrant workers in Central New York NEWS EDITOR More than 100 students, faculty, staff choose lives of loneliness and fear and community members gathered at Muller Chapel yesterday to mourn the loss of junior Andrea Morton. Morton passed away yesterday morn- ing because of a sudden medical condi- tion. Dave Maley, asso- ciate director of media relations, said Morton went to the Health Center last Th ursday when she fi rst felt ill. She was transported to Cayuga Medical Center and then on Friday was transferred MORTON passed from CMC to SUNY away suddenly Upstate Medical Uni- yesterday morning at the hospital. -

Poorest Nations Fall Behind As Vaccine Efforts Stagnate

P2JW110000-6-A00100-17FFFF5178F ****** TUESDAY,APRIL 20,2021~VOL. CCLXXVII NO.91 WSJ.com HHHH $4.00 DJIA 34077.63 g 123.04 0.4% NASDAQ 13914.77 g 1.0% STOXX 600 442.18 g 0.1% 10-YR. TREAS. g 8/32 , yield 1.599% OIL $63.38 À $0.25 GOLD $1,769.40 g $9.60 EURO $1.2038 YEN 108.14 Chauvin Case Goes to Jury After Day of Closing Arguments Nvidia’s What’s News Arm Deal Gets U.K. Business&Finance Security he U.K. government is Tstarting anational-secu- rity reviewofNvidia’s $40 Review billion deal to buy Arm from SoftBank,raising anew hur- dle for the proposal. A1 Officials begin probing A cryptocurrency that $40 billion takeover, was created as a joke ex- ploded into plain view on showing the strategic Wall Street, with asurge in role of semiconductors dogecoin sending its 2021 return above 8,100%. A1 BY STU WOO Credit Suisse said two AND ERIC SYLVERS executives in charge of its (2) prime brokerageunit will OL LONDON—TheU.K.govern- leave in the wake of the PO ment is starting anational se- S bank’s$4.7billion lossfrom curity reviewofNvidia Corp.’s the collapse of Archegos. B1 /PRES $40 billion deal to buy British TV T chip designer Arm from Soft- Musk’sinternet satellite UR BankGroup Corp., raising a venturehas spawned an un- CO DELIBERATION: The murder trial of DerekChauvin went to the jury MondayinMinneapolis afterSteveSchleicher,left, a newhurdle for an industry-re- likely allianceofrivals,regu- special assistant attorneygeneral forthe prosecution, and defenseattorneyEric Nelson made their closing arguments.