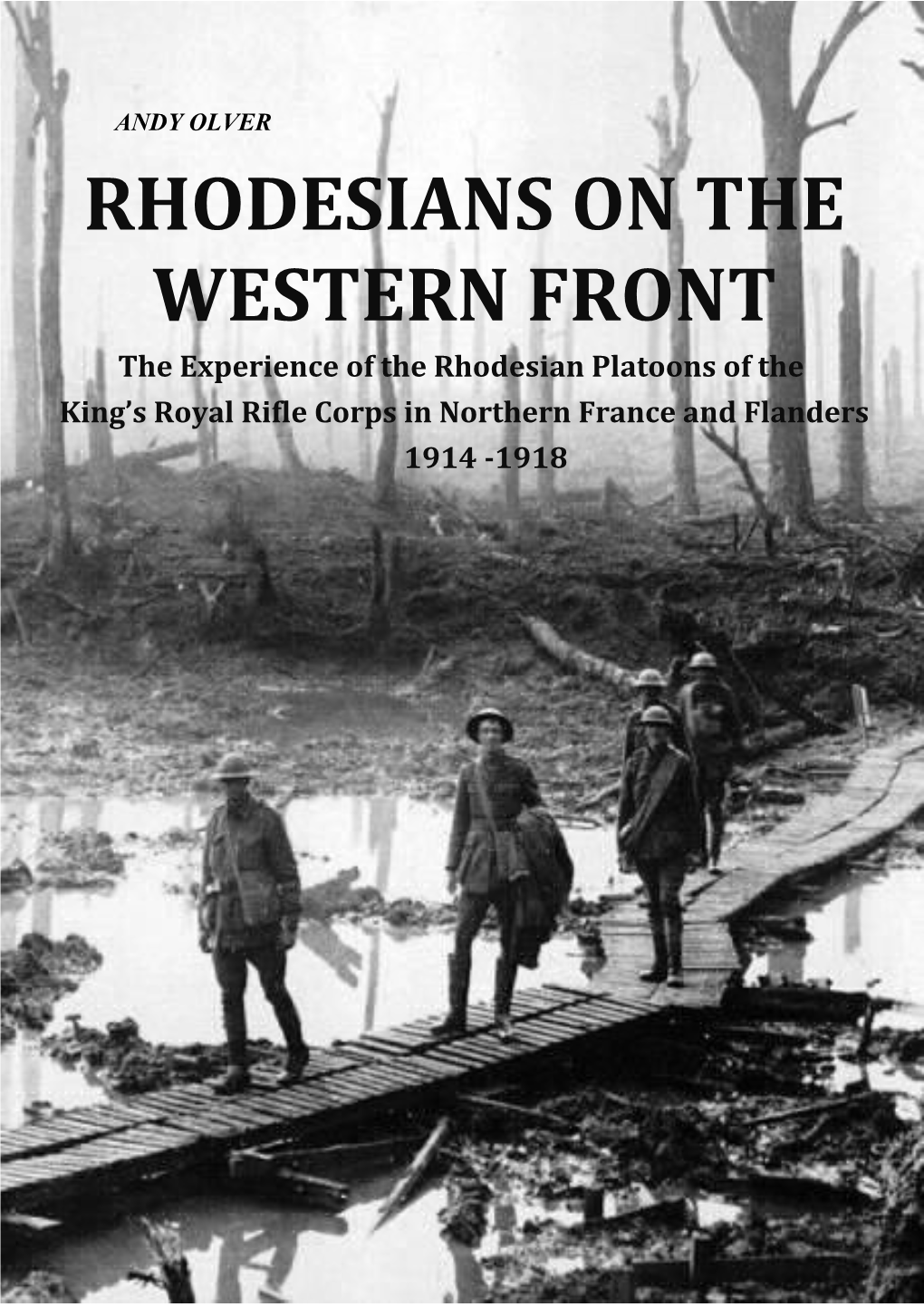

ANDY OLVER RHODESIANS ON THE WESTERN FRONT The Experience of the Rhodesian Platoons of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps in Northern France and Flanders 1914 -1918 Cover photograph - Australian gunners on a duckboard track in Château Wood near Hooge, 29 October 1917.

The photo was taken by WW1 photographer James Francis “Frank” Hurley, OBE. Hurley was an Australian photographer and adventurer. He participated in a number of expeditions to Antarctica and served as an official photographer with Australian forces during both world wars.

In 1917 Hurley joined the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) as an honorary captain and captured many stunning battlefield scenes during the Third Battle of Ypres. In keeping with his adventurous spirit, he took considerable risks to photograph his subjects, also producing many rare panoramic and colour photographs of the conflict. Hurley kept a diary in 1917-1918 describing his time as a war photographer. Preface

With the centenary of the commencement of the First World War falling shortly after the period covered by the 9th edition of the ‘Sunset Call’, the MOTH Matabeleland newsletter, I felt it fitting that I include a short four or five page account of the experiences of Rhodesians in WW1. Accordingly I chose to focus on the experience of the “Rhodesian” platoons of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps in the trenches of Northern France and Flanders. Well, that proved a far larger task than envisaged and this still incomplete account now measures some forty pages. As such it is now included as a separate supplement to the ‘Sunset Call’.

It is my intention to continue to research and provide a comprehensive account of the Rhodesian Platoons on The Western Front. The account, as it currently stands, essentially covers the period from the outbreak of war on 4 August 1914 to 20 March 1918, the date which marks the end of static entrenched warfare on the Western Front and a return to open warfare.

I need to apologise here for the incomplete source referencing and absence of a bibliography. This will be corrected in the larger “work in-progress”.

Andy Olver Bulawayo, 14 August 2014. Introduction

The First World War was sparked in the Balkans when, on 28 June 1914, Gavrilo Princip1 shot and killed the Austro-Hungarian heir, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, who had been invited to Bosnia and Herzegovina's capital, Sarajevo, to inspect army manoeuvers. Princip’s bullet struck the Archduke in the neck and his wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg, in the abdomen. Both died. It was “the shot that was heard around the world”. Spurred by imperialism, militarism, chains of alliances, nationalism, and finally the assassination of Franz Ferdinand, what had started out as a localised Balkans conflict, was quickly catapulted, with Britain’s declaration of war against Germany on 4 August 1914, into a global conflict - and the world was never the same.

Europe quickly became engaged in a gruesome struggle disfigured by mechanised warfare previously unimaginable: submarines, battleships, aircraft, tanks, machine guns, flame-throwers and legions of poison gas—the largest-scale use of chemical weapons in history. After the initial battles of 1914, both sides held an entrenched line that stretched some 700 kilometres from Nieuport on the Belgian coast to Pfetterhouse on the Swiss border. The trench line was the result of the stagnation of battle where both sides "dug in" and settled down to a war of attrition, with little movement for over three years. The name given to this fighting zone in France and Flanders, where the British, French, Belgian and (towards the end of the war) American armies faced that of Germany, is “The Western Front”.

The intense and mechanical destruction of Northern France and Flanders created a new and terrifying landscape that had, until then, only ever been imagined or seen in medieval visions of hell: one of mud, bloated corpses, barbed wire and shell-holes through which wound a series of rotten, death-strewn trenches - an inconceivable maze of thousands of miles of freezing, disease-ridden and rat-infested tunnels where men subsisted below the earth. They rose from this hell only to be fed into a far worse one—no man’s land - the human meat-grinder. The human cost of casualties and dead in such a grinding type of siege warfare would be recorded in the tens of thousands in a single day.

The First World War was a disastrously wasteful affair; one that Pope Benedict XV publicly declared an unjust war, a mad form of collective European suicide. The pontiff rightly judged that there were no salient moral issues dividing the combatants. These countries should not have been at war, let alone slaughtering their boys by the millions.

During this “war to end all wars ”, Southern Rhodesians served in over eighty British imperial regiments, but the largest concentration was in the regular 2nd and 3rd Battalions of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps (KRRC) where wholly “Rhodesian” platoons, numbering 60 to 90 men at full strength, were formed.

It was in the trenches of the Western Front that Southern Rhodesia’s main contribution to World War One was made and it is on that front and the major battles in which the “Rhodesian” Platoons of the KRRC fought between November 1914 to March 1918 (the 2nd and 3rd phases of the war 2), that this account focuses.

1 Gavrilo Princip was a Bosnian-Serb student and member of the secret Black Hand Society (a nationalist movement favouring a union between Bosnia-Herzegovina and Serbia). Princip was one of three men sent by the Serbian Army’s Intelligence Department to assassinate Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand during the latter’s visit to Sarajevo to inspect army manoeuvres in late June 1914.

2 The war on the Western Front was fought in 4 phases: Phase 1 (Aug to Nov 1914) - a war of encounter and movement, leading to both sides digging-in and trench warfare beginning; Phase 2 (Nov 1914 to Jul 1917) - entrenched warfare in which the British worked to the French strategy; Phase 3 (Jul 1917 to Mar 1918) - trench warfare in which British and Commonwealth forces begin to play a leading role; and, Phase 4 (Mar to Nov 1918) - return to open warfare as German offensives are held and Allied offensives succeed. THE EXPERIENCE OF THE RHODESIAN PLATOONS OF THE KING’S ROYAL RIFLE CORPS IN NORTHERN FRANCE AND FLANDERS 1914 -1918 ______

1. OUTBREAK OF WAR

Britain declared war on Germany at 23h00 GMT on Tuesday 4 August 1914. Word of the declaration reached Salisbury during the night. Early on Wednesday 5 August, the British South Africa Company (BSAC) administrator of Southern Rhodesia, Sir William Henry Milton, wired Whitehall: "All Rhodesia united in devoted loyalty to King and Empire and ready to do its duty”. Similar messages of support had been received from each of Britain’s overseas territories. In response King George V sent the following message to his Colonies:

I desire to express to my people of the Overseas Dominions with what appreciation and pride I have received the messages from their respective Governments during the last few days. These spontaneous assurances of their fullest support recall to me the generous, self-sacrificing help given by them in the past to the mother country. I shall be strengthened in the discharge of the great responsibility which rests upon me by the confident belief that in this time of trial my Empire will stand united, calm and resolute, trusting in God. -George R.I. (The Daily Mirror, 5 August 1914)

At around 8.00 am on 5 August Milton officially announced to his countrymen that Southern Rhodesia was at war. The ''Bulawayo Chronicle'' and “Rhodesia Herald” newspapers published special editions the same day to spread the news; it took about four days for word to reach the whole country.

The news of Britain’s declaration of war was greeted throughout its overseas possessions by British settlers with patriotic fervour. In Salisbury a packed meeting at the Drill Hall turned into stirring and emotional outpourings of support for the Mother country. In Bulawayo mass meetings, awash with pro-Empire sentiments, were held at the Drill Hall and Bulawayo Club. Gatooma prepared to form a special unit for military service, while in Umtali residents demonstrated their concern for Belgium which the German Army had just invaded. The enthusiasm to answer the call was infectious and all the talk was of war. By 13 August over 1,000 young Rhodesian men had volunteered for service. However it would be some four and a half months before the first Rhodesians would see action on the Western Front. Rhodesians leave for

As a commercial venture, the BSAC needed to carefully consider the financial implications of the war for its chartered territory should it commit directly to the war effort. In the face of the BSAC’s resulting inaction, the Rhodesian public’s frustration came close reaching boiling point. A number of letters were received by the Press strongly urging the BSAC to commit to the war effort and ‘German baiting’ became endemic. In September a number of German settlers were taken prisoner and sent to an internment camp in Johannesburg. Impatient and frustrated at the BSAC’s apparent inertia, many individuals paid their own way to England to join British Army units. Most of the colony's contribution to the war was made by Southern Rhodesians’ individually. By the end of October 1914 about 300 Rhodesian volunteers were on their way as part of the massive satanic spasm that was to spew forth a conflagration the likes of which the world had never before experienced. Throughout the duration of the war, which was expected to be over by Christmas, drafts of young Rhodesians would arrive on the Western Front. Though it was one of the few combatant territories not to raise fighting men through conscription, by the war’s end in November 1918, proportional to white population, Rhodesia contributed more manpower to the British war effort than any other British dominion, including Britain. White troops numbered 5,716, about forty per cent of white men in the colony. The Rhodesia Native Regiment enlisted 2,507 black soldiers, about thirty of whom scouted for the Rhodesia Regiment and around 350 served in British and South African units. Of a total of 7,436 Southern Rhodesians of all races, over 800 lost their lives on operational service during the war, with many more wounded.

______2. FORMATION OF RHODESIAN PLATOONS WITHIN THE KING’S ROYAL RIFLE CORPS (KRRC)

At the commencement of the war the renowned KRRC Regiment comprised four regular battalions – the 1st, 2nd, 3rd and 4th Battalions. On 12 August 1914 the 1st and 2nd Battalions, having enjoyed a five-year period of home service, left the comforts of home for France as members of the 1st and 2nd Infantry Divisions respectively, and by 23 August both battalions had taken up positions near Mons in Northern France.

In November 1914 the 3rd and 4th Battalions, drained by four and a half debilitating years in India, were recalled to their base at Winchester. On 21 December, after a brief period of training and re- fitting, both battalions were sent to France where, on 5 January 1915, they took over trenches from the French at Dickebusch near St. Eloi, north of Ypres. In October 1914, on board the ship that took the first draft of Rhodesians from Cape Town to Southampton was Henry Paulet, 16th Marquess of Winchester, who had links with Southern Rhodesia dating back to the 1890s. Coming across Captain John Banks Brady who led the Rhodesian volunteers, the Marquess asked where Brady’s party was headed. Brady said they were on their way to war in France. The Marquess suggested to Brady that since it might be difficult to prevent his men from being separated during the enlistment process, it might be wise for the Rhodesians to join the King’s Royal Rifle Corps3 (KRRC) where he could keep a close watch on them through his Men of the original Rhodesian Platoon of the KRRC connections with the Winchester-based regiment. Taken in November 1914 at the KRRC training depot at Sheerness before the Rhodesian platoon went to the Western Front. Centre of the second On arrival in England the Rhodesians underwent row from the front sit the Marquess of Winchester and Captain John Brady. Only 12 members of this original platoon survived the war. several weeks training at the KRRC training depot at Sheerness on the Isle of Sheppey in Kent. The training was intensive and went on from 06h00 to 21h00, seven days a week. While At Sheerness the Rhodesians broke the Regimental rifle range record of seven years’ standing. Most, if not all of the Rhodesians knew their way around a rifle, having spent much time in the Rhodesian bush hunting big game; whereas many of their English counterparts had never held a rifle. Each batch of Rhodesians that passed through Sheerness lived up to the reputation established by that first draft of being “crack” shots. In December the Rhodesians were sent to France, joining the 3rd Battalion KRRC (3/KRRC), mustering as No. 16 “Rhodesian” Platoon, ‘D’ Company, with Captain Brady as its commander. In the wake of the formation of an explicit KRRC “Rhodesian” platoon, Rhodesian volunteers began to concentrate in the KRRC and in particular, within the 2nd and 3rd Battalions, both of which raised Rhodesian platoons. The Regiment was soon thought of as Rhodesia’s ‘own’ regiment.

As the war progressed the KRRC raised a further 22 battalions. Rhodesians served in a number of these, but not in sufficient numbers to form “Rhodesian” platoons.

3 The King’s Royal Rifle Corps was not a Corps, but a Regiment. 3. IN NORTHERN FRANCE AND FLANDERS

During October and November 1914, the 1st and 2nd KRRC Battalions, both in France since August, had suffered terrible casualties at the First Battle of Ypres (21 Oct – 13 Nov). During the battle three companies of 2/KRRC had become isolated and despite putting up a desperate fight, were never seen again. Accordingly the Battalion needed to quickly make up its numbers and on 26 December a draft of newly arrived Rhodesians joined 2/KRRC on the Western Front. The Rhodesian draft was quickly formed into a “Rhodesian” platoon that soon earned for itself a great reputation for valour and good shooting. On 5 January, the 1st and 2nd Battalions joined the 3rd and 4th Battalions in the reserve trenches north of Ypres. When the Rhodesians arrived on the Western Front the first thing they saw were lines of wounded soldiers being taken to the rear. As they got closer they could feel the earth shake and hear the constant ‘crump crump’ of artillery shells. The sound was loud enough to make their ears ring and became their bone-shattering companion for the next three years. Next they saw a series of muddy trenches littered with the waste of war. Boxes, cart wheels, wire and often the bodies of the dead and dying were strewn everywhere. These were the reserve trenches, far enough from the battle for soldiers to try to grab a little rest from all the death and madness in the front line.

THE STRATEGIC OUTLOOK IN EARLY 1915 With the beginning of trench warfare in late 1914 both sides began assessing options for bringing the war to a successful conclusion. Overseeing German operations, Chief of the General Staff Erich von Falkenhayn preferred to focus on winning the war on the Western Front as he believed that a separate peace could be obtained with Russia if it was allowed to exit the conflict with some pride. This approach clashed with Generals’ Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff who wished to deliver a decisive blow in the East. As heroes of Tannenberg4 they were able to use their fame and political clout to influence the German leadership, and as a result, the decision was made in 1915 to focus on the Eastern Front. In the Allied camp there was no such discord. The British and French were keen to expel the Germans from the territory they had occupied since August 1914. For the French it was a matter of national pride and economic necessity as the occupied territory held much of France's industry and natural resources. Instead, the challenge faced by the Allies was where to attack. This choice was largely dictated by the Western Front terrain. In the south, the woods, rivers, and mountains precluded a major offensive, while the sodden soil of coastal Flanders5 fast turned into a quagmire during shelling. In the center, the highlands along the Aisne and Meuse Rivers too, greatly favoured the defender. As a result the Allies focused their efforts on the chalk lands along the Somme River in Artois and to the south in Champagne. These points were located on the edges of the deepest German penetration into France and successful attacks had the potential to cut off the enemy forces. In addition, breakthroughs at these points would sever German rail links east which would compel the Germans to abandon their position in France.

THE FIRST CHAMPAGNE OFFENSIVE (20 DECEMBER 1914 – 17 MARCH 1915) An assessment by the French High Command in November 1914 noted that the German offensive on the Western Front had ended and four to six German corps were being moved to the Eastern Front. Consequently, a French offensive would assist the Russian army on the Eastern Front by forcing the Germans to keep more forces in the west. As a result the First Champagne Offensive, a joint French- British initiative centered upon the Reims region, was planned.

4 The Battle of Tannenberg was perhaps the most spectacular and complete German victory of the First World War. The encirclement and destruction of the Russian Second Army in late August 1914 virtually ended Russia's invasion of East Prussia before it had really started.

5 Flanders refers to the entire Dutch-speaking and northern part of Belgium. Map of the 1914-1918 Western Front Battlefields The offensive, rather than a mass offensive, was essentially a series of on-going attacks against points of tactical worth. However, the Allies were up against a well-entrenched enemy and their gain in ground was minimal and costly. For the four regular KRRC battalions a trying period of alternate spells of trench warfare and rest with training and fatigues followed. Fighting continued without a break until mid-February, during which the Rhodesians sustained a number of casualties and attempted to come to terms with the suffering and horror of trench warfare.

For the Rhodesians, coming from the open sun-splashed southern African veld, the confinement, mud and winter’s cold alone, were a nightmare. The Rhodesians had only two blankets each and had to sleep as close as possible to one another just to survive. The winters’ could get so cold that water was carried to the soldiers as blocks of ice. Men would wake after a few hours sleep only to find their eyelids frozen shut. Their feet would swell to three times their normal size because they had been standing for a week in ice-cold water up to their knees. Ice would form around the rim of a boiling mug of tea after it had been carried just twenty paces. Within forty-eight hours of the Rhodesians reaching the trenches, Brady, then commanding the “Rhodesian” Platoon 3/KRRC, reported that some of his men had contracted frostbite.

In the trenches death was a constant companion and at once the Rhodesian platoons began suffering regular heavy casualties. In busy sectors the constant enemy shellfire brought sudden and random death. The uninitiated were quickly cautioned against their inclination to peer over the parapet into ‘No Man's Land’. Many soldiers died on their first day in the trenches from of a precisely aimed sniper's bullet.

Under these conditions the numbers of the Rhodesian platoons in 2nd and 3rd KRRC Battalions began to decline, their ranks being filled by newly arrived Rhodesian volunteers. Rhodesian volunteers continued to arrive piecemeal in England throughout the war, so Rhodesian formations on the Western Front received regular reinforcements in small batches. However, because casualties were usually concentrated in far larger groups, it would often take a few months for a depleted Rhodesian unit to return - Phoenix-like - to full strength. A cycle developed whereby Rhodesian platoons in Belgium and France were abruptly decimated and then gradually re-built, only to suffer the same fate on returning to the front line. Once in the trenches the Rhodesian’s shooting skills were clearly evident. Lieutenant General Sir Edward Hutton records that:

When the opposing forces first settled down to trench warfare the Germans very soon attained an ascendancy in sniping. The 2nd Battalion (KRRC), during the winter of 1914-15, received a draft of Rhodesians. A section of snipers was made up from them under Lieutenant L. C. Rattray. In the words of the 2nd Battalion 'Records': “Thanks to their enterprise and accurate shooting, we soon got the upper hand of the German snipers, and this ascendancy was maintained throughout the campaign and in every section of the line before the Battalion had been three days in the trenches. (A Brief History of the King’s Royal Rifle Corps, 1755-1918, 2nd Edition, p. 57).

Following a pause by the French in mid-February to re-organise, the offensive was resumed without any significant gains until 17 March when it was called off by the French, owing to the strength of German counter-attacks, combined with a costly lack of success. The First Champagne Offensive was a failure with casualties in the region of 90,000. It was also a harsh lesson for the Rhodesian soldier on how to stay alive in the trenches.

THE SECOND BATTLE OF YPRES (19 APRIL TO 13 MAY 1915)

The Second Battle of Ypres was the only major attack launched by the German forces on the Western Front in 1915. The attack was used as a means of diverting Allied attention from the Eastern Front and to remove the Ypres salient by introducing a new weapon, chlorine gas.

In the first week of April two British Divisions (which included the 3rd and 4th KRRC battalions) and a Canadian and the French (Algerian) Division, were moved to a bulge in the Allied line in front of the city of Ypres. This was the infamous Ypres salient where the British and Allied line pushed into the German line in a concave bend. The Germans held the higher ground and were able to fire into the Allied trenches from the north, south and east.

On April 22, following an intensive artillery bombardment, 5,700 canisters of chlorine gas was released into a light northeast wind. Captain Hugh Pollard, in his “The Memoirs of a VC (1932)”, describes what followed:

Dusk was falling when from the German trenches in front of the French line rose that strange green cloud of death. The light north-easterly breeze wafted it toward them, and in a moment death had them by the throat. One cannot blame them that they broke and fled. In the gathering dark of that awful night they fought with the terror, running blindly in the gas-cloud, and dropping with breasts heaving in agony and the slow poison of suffocation mantling their dark faces. Hundreds of them fell and died; others lay helpless, froth upon their agonized lips and their racked bodies powerfully sick, with tearing nausea at short intervals. They too would die later – a slow and lingering death of agony unspeakable. The whole air was tainted with the acrid smell of chlorine that caught at the back of men's throats and filled their mouths with its metallic taste.

The gas affected some 10,000 troops, half of whom died within ten minutes of the gas reaching the front line. It also left a gaping four-mile hole in the Allied line.

German troops pressed forward, threatening to sweep behind the Canadian trenches and put fifty thousand Canadian and British troops in deadly jeopardy. Here, through terrible fighting, withered with shrapnel and machine-gun fire, violently sick and gasping for air through urine soaked and muddy handkerchiefs, the Rhodesian platoon fought, sustaining terrible losses. All through the night the British and Canadian troops fought to close the gap. Little ground was gained and casualties were extremely heavy, but the attacks bought some precious time to close the flank. On 24 April the Germans, aiming to obliterate the salient once and for all, launched a violent bombardment followed by another gas attack. This time the target was the Canadian line, which bravely held on until reinforcements arrived.

Following a failed Allied counter-attack, the Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force (B.E.F.), Field Marshal John French, executed a planned withdrawal on 1-3 May. On 5 May a further withdrawal was made nearer to Ypres with the Canadians and 4/KRRC in the front-line and 3/KRRC in close support. On the 9th, 3/KRRC relieved the Canadians who had been badly mauled, while 4/KRRC fought hard to repulse a German infantry attack.

On 10 May, after a large German bombardment and strong covering rifle and machine-gun fire, a German infantry advance was halted, enabling the 3rd and 4th KRRC Battalions to lend close support to the Canadians against a concentrated enemy attack to the south. The two KRRC Battalions fought side-by-side with great effect and individual acts of gallantry were many. By 18h00 the bombardment ceased and further advances by the enemy were checked. By midnight the bare remnants of 4/KRRC were withdrawn and on the following day moved to a temporary bivouac where the men lay down to sleep for a full night's rest after twenty-six battle-intensive days in the trenches.

Two nights later, on the night of 12 May, 3/KRRC was the recipient of yet another intense bombardment which called for reinforcement by the North Somerset Yeomanry. Together they defeated the German infantry attempt to advance. Finally, on the 14th, after acquitting themselves with splendid gallantry and a continuous spell of twenty-five days of active work in the trenches, 3/KRRC and the men of the now much depleted Rhodesian platoon, were at last able to get much needed rest in a bivouac four miles west of Ypres.

The resolute valour of the two KRRC battalions was rewarded by a message from H.Q. Army Corps: "The G.O.C. is lost in admiration at the way in which the 3rd and 4th Battalions have stuck out the pounding which they have received." On 14 May 4/KRRC, sadly reduced, merged with the remnant of the Canadian Light Infantry and marched again into the trenches until 17 May, when the Battalion moved to billets in the rear.

The Rhodesian Platoon 3/KRRC incurred heavy losses during the battle and the fatalities for the two KRRC battalions were numerous, losing 1,035 men. 3/KRRC lost 542 men - seventeen officers and 525 other ranks killed, wounded and missing while 4/KRRC, in the three days from 8 to 10 May, lost 493 men - fifteen officers and 478 other ranks killed, wounded and missing.

Total losses during the battle are estimated at 69,000 Allied troops (59,000 British, 10,000 French), against 35,000 German, the difference in numbers being explained by the use of chlorine gas. The Germans' innovative use of gas set the trend for the rest of the war.

During the Second Battle of Ypres, Private John Condon, sheltering in a trench to escape from the artillery and grenade onslaught of the advancing enemy, was killed by chlorine gas. Private Condon was just fourteen years old. The boy soldier had claimed that he was eighteen when he enlisted two years earlier. John Condon was World War One’s youngest British fighter and just one of thousands of lads who lied about his age to fight for his country. (Daily Mirror, 29 July 2014) 6. It was also during the Second Battle of Ypres that Canadian Army surgeon John McCrae was driven to write the famous WW1 poem, “In Flanders Fields”.

THE BATTLE OF AUBERS RIDGE (9 MAY 1915)

It was not long before the Rhodesian platoon of 2/KRRC was in the thick of it. A Franco-British offensive, intended to exploit the German diversion of troops to the Eastern Front by pushing the Germans off the dominating high ground of the Loretto and Vimy Ridges north of Arras, and disrupting vital German rail supply routes, was planned. The British attacks on the German line took place on the flat Flanders plain at Aubers Ridge and Festubert.

6 The legal age limit for armed service overseas was nineteen. The British First Army, employing a pincer movement, was to attack two areas of the German front line either side of the Neuve Chapelle battlefield. The Southern pincer, comprising the 2nd Infantry Brigade, was to attack on a one and a half mile front from the Rue du Bois. The 2nd Infantry Brigade comprised: Fire and support trenches - 1st Northamptons and 2nd Royal Sussex Battalions; 2nd line - 2nd KRRC and 5th Royal Sussex Battalions, and 3rd line - 9th Liverpools and 1st Loyal North Lancashire Battalions. The Northern pincer, comprising battalions of IV Corps, was to attack on a one mile front opposite Fromelles. The attacks were intended to make two breaches in the German defences after which the infantry were to advance to and hold Aubers Ridge about two miles beyond.

In the weeks leading up to the attack the Germans had energetically improved the defences in this area and the troops opposite 2/KRRC shouted across that they were expecting an attack. Air observation had also revealed that the German front line defences at Aubers had been strengthened.

During the night of 8 May 2/KRRC moved into battle positions while the Royal Engineers bridged a large ditch between the support and fire trenches, and also the ditches in front of the Brigade’s fire trench.

The morning of 9 May was bright and good for observation and at 05h00 the British guns bombarded the enemy’s breastworks, wire and support trenches until 05h30 when the shelling became intense. Clouds of dust were raised so that it was not possible to see much beyond the breastworks.

During the intense bombardmentthe firing line and supports of the 2nd Royal Sussex and 1st Northamptons, climbed over the parapet, two men of each platoon carrying a light bridge, and ran forward to gain a line about eighty yards from the enemy’s parapet. The machine-gun fire was heavy, cutting the men down, even on their own ladders and parapet steps, but they pressed forward as ordered. When the bombardment ceased at 05h40 the men of 2/KRRC and 5/Royal Sussex were arriving in the vacated fire trenches. Shortly after their arrival, two 2/KRRC Companies – one of which included the Rhodesian Platoon - and nearly all 5/Royal Sussex, crossed the breastwork and went forward in support. As soon as the British guns ceased, the enemy’s fire increased and the two leading battalions lost very heavily, chiefly from the German machine-guns which swept across the few yards of open ground between the British trenches and those of the enemy. The men of 2/KRRC and 5/Royal Sussex continued to advance bravely but only very few succeeded in getting as far as the enemy’s wire with many wounded or pinned down in No Man’s Land by withering rifle and machine-gun fire.

At 06h05, 2/KRRC sent a message that the enemy’s wire had not been cut by the bombardment, and later a similar report was received from 1/Loyal North Lancs. At 06h20 the assaulting troops could advance no further.

At 08h20, without any change in the situation, the 1st Guards Brigade was ordered to relieve the 2nd Infantry Brigade which was to withdraw and re-form behind the breastworks. This was done as far as possible, but as any movement by those who were lying out between the British and the enemy’s parapets at once attracted enemy fire, only a few men managed to make it back to their trenches before dark, with hundreds more – Rhodesians among them - still pinned down in No Man's Land, unable to advance or fall back.

Lt. Colonel Langham, Commander of the 5/Royal Sussex, which had to ‘mop up’ after the assault wrote: We had, therefore, to mop up on the front of the two assaulting Battalions and it means sending up a third Company to follow the KRRCs and 'mop up' behind the Northants. After a bombardment of 40 minutes the advance began. Three Companies of the 2nd Battalion [KRRC] and all the Northants went out over and got to from 40 to 80 yards from the German lines. "C" Company, less one platoon, “A" Company, less one platoon and the whole of "B" Company, went out in the second line, and two Companies of the KRRCs. Then the most murderous rifle, machine gun and shrapnel fire opened and no one could get on or get back. People say the fire at Mons and Ypres was nothing to it. No ends of brave things were done, and our men were splendid but helpless. They simply had to wait to be killed. After some considerable time, we got orders to retire, but this was easier said than done. Some men were 300 yards out from our parapet, many dead and some even on fire; and in two cases, men of ours who were burning alive, committed suicide, one by blowing out his brains and another cut his own jugular vein with the point of his bayonet.

David Tuffley provides the following first-hand account by his maternal grandfather, Private Albert Money, who fought in a 2/KRRC Company beside the men of the Rhodesian platoon:

We got up alright on the night of the 8th, it was very cold, they gave us a good dose of rum in the morning around 5:00 a.m. I gave my mate mine, he was shaking but not with fear, he was a brave fellow but that was his second time out, he went through all the battle of Mons and the Aisne and Marne and at Ypres. We had a fine Captain, Hesseltine, that was his second time, but he said to us, "We are going into this charge so we will do the best we can”. None of that silly talk, we must do this and do that, he spoke like a man, they all said they would follow him to the last man and I believe them too. The poor old Northamptons were in the firing line and we [2/KRRC] were reinforcements. The bombardment started at 0500, steady for half an hour and 10 minutes as hard as they could go, about five to seven hundred guns going off, all sorts. Just at half past five the Northamptons had to leave their trenches and get up to the Germans under the ten minutes, heavy bombardment, as soon as they left we had to rush across the open and take them over [occupy the front line] while the Northamptons charged. The Germans were pouring shrapnel between the reserve trenches and the firing line. We could see the Northamptons going over the open in good order, through the smoke. It was simply raining lead, what with shells and machine guns, they had to get over a bit of a river, three or four yards wide and ten feet deep, nearly full of barbed wire. Our engineers put small bridges over the night before, just room for one man to run over...a good target and playing on them with machine guns, not much chance to get over. Some got across and some tried to jump across the water. If you got in it, then ten to one you would never get out, no chance at all if you were wounded. That is where a lot of the missing of the Northamptons are, poor fellows. We started over to reinforce them when they got half way, no time to see who was dropping. I saw two of my section get hit, I got about 250 yards when I got hit...I stopped one through the hip but had sense enough not to stop, the ditch was only eight yards in front. I got there and stayed, had a look to see how the wound was, cut all my equipment off and had a rest. The ditch was full of wounded and dead. My leg was dead, could not move it, fellow nearly blind with blood got my waterproof off to cover me up with and then the order came along to tell the Northamptons and the King's Royal Rifles to get back the best way they could. Couldn't take the position and no more reinforcements. They were coming back one at a time, those wounded in the ditch where I was all started back, crowding over me so I was left with the dead. The ditch was very narrow and only two feet deep and I was lying the wrong way around to get out. Tried to turn around but no hope, put the waterproof sheet over me and had another rest. I knew it was no use staying there if they made a counter charge so had another try and got around and pulled myself along the ditch hand over hand and into the one with water; had a rest every ten or fifteen yards. Got out once but could not get the leg out hanging over the side, but the Germans saw me and the bullets started spitting all around, so just rolled in again. I got up to our wire entanglement and there was a great shell hole so could get no nearer. One of the Black Watch had been watching me coming along, he called over to me and asked if I could get any nearer. I said "No", and he said "Right, I will come and get you over the top". He came, got in the shell hole and pulled me over his back and up to the parapet and dumped me on the top and some others pulled me over, no time for gentle handling. Then he went over again and brought in another, he went over himself then went under fire again in the open and went to some of the dead and got four [waterproof] sheets, overcoats and water-bottles and fixed the two of us up. I will never forget his bravery and kindness. The last I saw of him he said "I am going in this next charge." I wished him luck, but before he went I know for a fact he went back and brought four more fellows who were wounded. I am sorry I did not ask his name. (‘A Soldier’s Tale: Wounded at Battle of Aubers Ridge, May 1915’, Griffith University, Australia. Web site: http://www.ict.griffith.edu.au/~davidt/ z_ww1_slang/). A second bombardment and attack was planned for 11h30 but was cancelled owing to the extremely heavy casualties of the 2nd Brigade. Instead, the 1st Brigade would carry out the attack. At 17h00 the 1st Brigade moved up into the front trenches while 1/Loyal North Lancs were to hold the fire trench during the attack of the 1st Brigade. The bombardment commenced at 17h20 following which the 1st Brigade attacked from the left half of the line, the Black Watch and Cameron Highlanders being the assaulting battalions. As the assaulting troops advanced, many officers and men of the 2nd Brigade who had been lying out in the open since early morning, joined in the assault. At 18h15 1/Loyal North Lancs was ordered to support the Black Watch, but a few minutes later, when it became apparent that the 1st Brigade attack had no chance of getting through, this was cancelled.

The Northern pincer assault achieved its first objective and the Rifle Brigade bombers extended the trench system they occupied to 250 yards broad. However, by 06h10 the front and communication trenches were very crowded and chaotic; German shelling added to the confusion and the fire across No Man's Land was so intense that forward movement was all but impossible.

At 02h30 on 10 May, British units that had made it to the German lines were withdrawn and all further orders for renewing the attack were cancelled.

Mile for mile, Division for Division, Aubers Ridge had one of the highest rates of loss during the entire war. British losses on 9 May were 11,497 of which 451 were officers, the vast majority of which were sustained within yards of their own front-line trench. The Rhodesia Platoon sustained heavy losses with the Battalion losing 251 men, including eleven officers. Total Southern pincer casualties were 6,696 of which 256 were officers. Northern pincer casualties were 4,801, of which 195 were officers.

Aubers Ridge was an unmitigated disaster for the British army. No ground was won and no tactical advantage gained. It is very doubtful if it had the slightest positive effect on assisting the main French attack to the south which did not quite achieve the capture of the crest of Vimy Ridge despite the expenditure of 2,155,862 shells!

By the end of the offensive there were approximately 216,000 casualties - 100,000 French, 26,000 British and 90,000 German.

After the First Champagne Offensive the Western Front under British control in the Artois and Flanders sectors enjoyed a relatively quiet summer with no major attacks being attempted, although both sides continued to lose hundreds of men to sporadic shelling, sniper fire and enemy raids. For the men of the 2/KRRC Rhodesian platoon, four months of severe trench work followed during which the platoon sustained its usual weekly toll of casualties. Even in 'quiet times' a battalion could lose fifty men each month. In addition to these ongoing losses the Rhodesian platoons lost a large number of men to officer training. By mid-1915 so many Rhodesians were withdrawn for officer training that Captain Brady was forced to appeal for more volunteers through the Salisbury and Bulawayo presses. During their several months on the front line the Rhodesian’s natural leadership and fighting qualities had come to the fore. They and other colonial troops were generally regarded as being physically superior to their British comrades and displaying more intelligence, imagination and initiative. For their sins the Rhodesians were often given specialised and dangerous work such as the “post of honour”- the trench, crater or position closest the enemy. Rhodesians excelled as snipers, ‘bombers’ (specialised grenade throwers) or Lewis gunners. At one stage in ‘D’ Company 2/KRRC, all the ‘bombers’ were Rhodesians, as were the best snipers, Lewis gunners and other specialists. Wherever Rhodesians fought on the Western Front, they were conspicuous. A member of the proud Indian Sikhs said of the ‘Africans’; “English Tommy good, Australian very good, but Africans go like hell plenty much”. The Rhodesian’s became particularly proficient at carrying out of raids across No Man’s Land, a task feared and dreaded by most soldiers. Trench raids were small scale attacks on an enemy position. Surprise was everything, for an expected raiding party could literally be cut to pieces by rifle and machine-gun fire. On occasion raids would develop into dramatic and bloody miniature battles as vigilant enemy machine-gunners detected the approach of the raiding party. Raids were made by both sides and always took place at night for reasons of stealth. Small teams of men would blacken their faces with burnt cork before crossing the barbed wire and other debris of No Man's Land to infiltrate enemy trench systems. Trench raiding was very similar to the brutality of medieval warfare insofar as it was fought face-to- face with crude weaponry. Trench raiders were lightly equipped for stealthy, unimpeded movement. Typically raiding parties were armed with deadly homemade trench raiding clubs, bayonets, entrenching tools, trench knives, hatchets, pickaxe handles and brass knuckles. The choice of weaponry was deliberate: the raiders' intention was to kill or capture people quietly. Trench raiders were also armed with modern weapons such as pistols and hand grenades, though these were only used in an emergency. Standard practice was to creep slowly up on the sentries guarding a small sector of an enemy front line trench and then kill them as quietly as possible. Having secured the trench the raiders would complete their mission objectives as quickly as possible, ideally within several minutes. Often grenades would be thrown into dugouts where enemy troops were sleeping before the raiders left the enemy lines to return to their own. Trench raiding had multiple purposes. Typically, the intention would be to capture, wound or kill enemy troops; destroy, disable or capture high value equipment such as the MG08 machine gun; gather intelligence by seizing important documents or enemy officers for interrogation; reconnaissance for a future massed attack during daylight hours; or to keep the enemy feeling under threat during the hours of darkness, thereby reducing their efficiency and morale. Of the trench raid, Edmund Blunden (in Leo van Bergen, Before My Helpless Sight - Suffering, Dying and Military Medicine on the Western Front 1914 – 1918) says it is the ideal way for soldiers to commit suicide without ever being found out, since anyone who volunteered to take part had a good chance of not coming back. Blunden states this repeatedly in his book. He writes that the word “raid” may be defined as the one in the whole vocabulary of the war which instantly caused a sinking feeling in the stomach of ordinary mortals. Blunden states, “I do not know what opinion prevailed among other battalions, but I can say that our greatest distress at this period was due to that short and dry word – ‘raid’ ”. The Rhodesians had become adept at this form of warfare.

THE SECOND CHAMPAGNE OFFENSIVE (25 September - 6 November 1915) In the autumn of 1915 the French and British Armies carried out a second large-scale, two-pronged offensive against the German positions which, by this time, were well-consolidated and proving increasingly difficult to penetrate. The Second Champagne Offensive had the objective of forcing the German Third and Fifth Armies in the Argonne sector to withdraw along the Meuse river towards Belgium. A simultaneous attack by French and British forces from Vimy Ridge to La Bassée, called the Artois-Loos Offensive (25 September - 15 October 1915), aimed to break through the German Front in Artois. This would compel the German Second and Seventh Armies, caught between the two attacks, to pull back to the Belgian border in order to protect their road and rail routes on the Douai plain. The Artois-Loos offensive saw the first use of a gas cloud weapon by the British Army at the Battle of Loos. It was at this battle that the Rhodesian platoon 2/KRRC, which had already experienced countless horrors and sustained heavy casualties, was to experience more tragedy. Captain Brady, who had transferred to 2/KRRC some two months earlier, was to be a part of the experience. Recognising the obvious signs of impending attack, the Germans spent the summer strengthening their trench system, ultimately constructing supporting line fortifications three miles deep.

THE BATTLE OF LOOS (25 September - 8 October 1915) The Battle of Loos involved fifty-four French and thirteen British divisions on a front of some ninety kilometres running from Loos in the north to Vimy Ridge in the south. On 21 September the British began a four-day artillery bombardment of the German lines, intent on destroying the enemy trenches and clearing the barbed-wire entanglements. Over 250,000 shells were fired, seriously depleting the British store of munitions.

Order of Battle – Battle of Loos At 06h30 on 25 September the attack was launched. The 1st Division, of which the 2/KRRC and the “Rhodesian” Platoon were a part, took the centre, facing a section of the line known as "Lone Tree," named after the only tree still standing between the two lines. The attack was to commence with the release of chlorine gas which was expected to blow into the German lines. This was to be followed immediately by an attack, with the honour of “going over” first, being given to the 2nd Infantry Brigade with 2/KRRC and the 1/Loyal North Lancs in the forefront. At 06h00 the whistles blew and the gas and smoke bombs were fired while the two battalions went over the top, walking or trotting towards the German trenches with rifles at the high port and bayonets fixed. Unfortunately, before the gas had reached half the distance across, the wind changed and blew it back onto the advancing battalions causing 2,500 casualties, though only seven died from the gas. Captain Brady and a number of Rhodesians were gassed but all were able to keep advancing7. Having endured the chlorine gas, 2/KRRC crossed No Man’s Land under the protection of a thick blanket of smoke, but it was the very thickness of it that was their undoing. It was not until the German trenches near Lone Tree had been reached that it was seen that the trenches were intact and strongly covered by wire. Regardless, 2/KRRC and 1st Loyal North Lancs, with the 2nd Sussex in

7 By 6 July 1915, the entire British army was equipped with the "smoke helmet" which was a flannel bag with a celluloid window, which entirely covered the head. In April 1916 the more effective British small box respirator was first introduced to British soldiers - a few months before the Battle of the Somme. By January 1917, it had become the standard issue gas mask for all British soldiers. immediate support continued the attack, but no progress could be made. Despite the great sacrifice and gallantry displayed by all ranks, the attack proved fruitless and after suffering great loss, 2/KRRC had to be withdrawn until the regiments on the flanks, more fortunate in finding the enemy's entanglements destroyed, had carried the Lone Tree trenches and taken some 400 prisoners. During the battle the Rhodesian Platoon suffered devastating casualties. The British attack achieved some success north of Loos and by the end of the first day had passed through Loos village and reached the outskirts of the industrial town of Lens. There was also some success in the north where a German strong point - the Hohenzollern Redoubt - was stormed and taken. Elsewhere, the soldiers discovered that neither the German trenches nor the barbed-wire had been cleared by the four-day bombardment and they found themselves pinned down in No Man's Land by intense enemy artillery and machine guns. Worthy of mention here is that despite these setbacks, the controversial General, Douglas Haig (nicknamed “The Butcher”), then Commander of I Corps, requested that two additional “New Army” 8 Divisions, that had never seen combat, be brought forward. The “New Army” Divisions attacked on the afternoon of 26 September. The delay in waiting for the New Army Divisions had allowed the German Fourth Army to bring in reserves which reinforced a new German Second Position located on higher ground with good views across the British attack area. When the New Army attacked, the German machine guns went to work, cutting them down by the hundreds. German soldiers climbed above their parapets and fired their rifles into the mass of men trying to advance, and still the New Army columns kept coming, and still the German machine guns fired. Finally, the British could go no further, blocked by impenetrable barbed-wire and brutal machine-gun and rifle fire. A German Regimental Diarist described the scene. Never had the machine-gunners such straightforward work to do nor done it so unceasingly. The men stood on the fire-step, some even on the parapets, and fired exultantly into the mass of men advancing across the open grassland. As the entire field of fire was covered with the enemy's infantry the effect was devastating and they could be seen falling in hundreds. A German soldier provides the following account: We were very surprised to see them walking. We had never seen that before. The officers went in front. I noticed one of them walking calmly, carrying a walking stick. When we started firing we just had to load and reload. They went down in their hundreds. You didn't have to aim. We just fired into them. The fierceness of the fighting during the Battle of Loos was such that only 2,000 of the 8,500 soldiers killed on the first day of the attack have a known grave. The death toll at Loos was greater than in any previous battle of the war. During the battle 2/KRRC lost 506 men – eighty-six killed, 328 wounded, seventy-six gassed and nineteen missing. Among those killed at the Battle of Loos was Second Lieutenant John Kipling (1/Scots Guards), the only son of Nobel Prize-winning author Rudyard Kipling. A shell blast had apparently ripped off young John Kipling’s face and with the fighting continuing, his body was never identified. Rudyard Kipling later wrote a haunting elegy to his son and to the legions of sons lost in the Great War:

That flesh we had nursed from the first in all cleanness was given To be blanched or gay-painted by fumes – to be cindered by fires To be senselessly tossed and re-tossed in stale mutilation From crater to crater. For this we shall take expiation. But who shall return us our children?

During the battle the British suffered 50,000 casualties. German casualties were estimated at approximately half the British total. The British failure at Loos contributed to Haig's replacement of

8 The New Army, often referred to as Kitchener's Army or, disparagingly, Kitchener's Mob, was an (initially) all-volunteer army formed in the United Kingdom following the outbreak of hostilities in the First World War. It was created on the recommendation of Horatio Kitchener, then Secretary of State for War. The first New Army divisions were used at the Battle of Loos. General John French as Commander-in-Chief of the B.E.F. at the close of 1915, this despite Haig’s reckless sacrifice of thousands of British troops. By this stage of the war the Rhodesian platoons had suffered appalling losses, only to be replenished by new drafts from Southern Rhodesia, to be followed later by further losses and further drafts. However, despite their losses, the Southern Rhodesians had distinguished themselves through their gallantry and had gained a reputation as brave and valiant soldiers and their sniping skills continued to receive wide acclaim.

In November 1915, the 3rd and 4th KRRC Battalions, having endured twelve grinding months on the Western Front, were sent to Salonika in neutral Greece to assist the Serbian Army which was in full retreat from Bulgarian forces. ______4. THE SALONIKA CAMPAIGN OCTOBER 1915-NOVEMBER 1918

The Salonika Front is arguably one of the most forgotten in terms of where British and Commonwealth troops served in the Great War. The Salonika Front has become known as the “forgotten front” and the troops that fought there – “The Gardeners of Salonika”9 - could well be called the “forgotten army” of the First World War. The British troops of the British Salonika Force (B.S.F.) had many names for this theatre of war, some unpublishable, but the commonplace ‘Muckydonia’ (a play on the region’s other name, Macedonia) summed up how many of them felt about being there. The campaign was, from the British perspective, always destined to be a 'side show'. But when the moment came for the force to push north in September 1918, its assault along the front into Macedonia was so intense it bore comparison with the heaviest fighting of the Great War.

A result of the First Balkan War (1912-13) fought between the Balkan League, comprising Greece, Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro, and the Ottoman Empire, was a reduction in size of the Ottoman Empire and the creation of an independent Albanian state while enlarging the territorial holdings of Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro and Greece. Dissatisfied with its share of the spoils, Bulgaria, attacked its former allies, Serbia and Greece, in June 1913 (the Second Balkan War) - a result of which was the loss to Bulgaria of most of its Macedonian region to Serbia and Greece.

Following the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in June 1914, Austria-Hungary delivered a series of ten demands to Serbia intentionally made unacceptable, intending to provoke a war with Serbia. When Serbia agreed to only eight of the ten demands, Austria-Hungary declared war on 28 July 1914. Serbia had an experienced army, having fought two successful Balkan wars in the previous two years, but it was also exhausted and poorly equipped, which led the Austro-Hungarians to believe that it would fall in less than a month. Serbia's strategy was to hold on as long as possible, while also constantly worrying about its hostile neighbour to the east, Bulgaria.

By 12 August, Austria-Hungary had amassed over 500,000 soldiers on Serbian frontiers, and Serbia mobilised some 450,000 troops, but because of the poor financial state of the Serbian economy and losses in the Balkan Wars, the Serbian army lacked much of the modern weaponry and equipment necessary to engage in combat with its larger and wealthier adversaries. Over the course of the following thirteen months the Serbians fought several battles against the Austro-Hungarian and Bulgarian armies, which though not suffering ultimate defeat, severely weakened the Serbian army.

Germany was also keenly interested in Serbia in that if Serbia fell, they would then have a rail link from Germany, through Austria-Hungary and down to Istanbul and beyond. This would allow the Germans to send military supplies and troops to help the Ottoman Empire.

On 7 October 1915 the Austro-Hungarians and Germans launched an assault on Serbia crossing the Drina and Sava rivers and after fierce street-by-street fighting, occupied Belgrade on 9 October. Serbia had appealed to the British and French governments for military support and in early October, a small two Division strong Franco-British force began landing at Salonika on the Aegean Sea coast. French forces numbered 34,000 and the British forces (the 10th ‘Irish’ Division), 14,000. Additional British reinforcements were soon to follow, including the Rhodesian Platoon of 3/KRRC. The French were under the command of General Sarrail and the British under Lieutenant General Sir Bryan Mahon.

On 14 October 1914, the Bulgarian Army attacked Serbia from the north of Bulgaria towards Niš and from the south towards Skopje. The Bulgarian First Army defeated the Serbian Second Army at the Battle of Morava, while the Bulgarian Second Army defeated the Serbians at the Battle of Ovche Pole.

9 Clemenceau, France’s wartime leader, scornfully branded the Allied forces at Salonika as “The Gardeners of Salonika” as they were perceived as doing little more than digging trenches. With the Bulgarian breakthrough, the Serbian position became untenable; the main army in the north (around Belgrade) could either retreat, or be surrounded and forced to surrender.

Meanwhile, the newly arrived French and British divisions had marched north from Salonika under the command of General Sarrail. However, the British War Office was reluctant to advance too deep into Serbia, so the French divisions advanced on their own to the Vardar River. In the Battle of Kosovo the Serbs made a last and desperate attempt to join the two Allied divisions that had made a limited advance from the south. However, by the end of November the French Division had to retreat in the face of massive Bulgarian assaults. The British at Kosturino were also forced to retreat and by 12 December all Allied forces were back in neutral Greece. Fortunately the Bulgarian Army was not permitted by the German High Command to enter Greek territory, as they still hoped that the unpredictable Greeks would enter the war on their side.

With no relief coming from the Allied forces, Serbian army commander, Marshal Putnik, ordered a full retreat, south and west through Montenegro and into Albania. The weather was terrible, the roads poor, and the army had to help the tens of thousands of civilians who retreated with them with almost no supplies or food left. But the bad weather and poor roads worked for the refugees as the Central Powers forces could not press them hard enough, and so they evaded capture. Many of the fleeing soldiers and civilians did not make it to the coast, lost to hunger, disease and attacks by enemy forces and Albanian tribal bands. The circumstances of the retreat were Serbian Army during its retreat towards Albania disastrous and all told, only some 155,000 Serbs, mostly soldiers, reached the Albanian coast on the Adriatic Sea. Despite the Central Powers' victory, the battered, seriously reduced and almost unarmed Serbian Army was carried to various Greek islands (many to Corfu) by Allied transport ships. The evacuation of the Serbian army from Albania was completed on 10 February 1916. The survivors were so weakened that thousands of them died from sheer exhaustion in the weeks after their rescue. Marshal Putnik had to be carried during the whole retreat and he died a bit more than a year later in a hospital in France. Six months after its evacuation, and having been rebuilt almost from scratch, the Serbian Army was again in the front lines.

It had been an almost complete victory for the Central Powers at a cost of around 67,000 casualties as compared to around 90,000 Serbians killed or wounded and 174,000 captured. The only flaw in the victory was the remarkable retreat of the Serbian Army. As a result of Serbia’s defeat, the Germans opened the railway line from Berlin to Constantinople, allowing Germany to prop up the Ottoman Empire.

Between November 1915 and January 1916 the British reinforcements – the 28th, 22nd, 26th and 27th Divisions - in that order - landed at Salonika. As part of the 27th Division were the 3rd and 4th KRRC Battalions of the 80th Infantry Brigade.

After withdrawing from Serbia the Allies first priority was to set up defensive positions around Salonika, assuming that Bulgarian forces would try and advance into Greece. The expected invasion never took place. Instead, the Bulgarians dug in and fortified their positions along the Greek-Serb border from the coast of Albania to Lake Doiran and the Bulgarian border. In their turn, the Franco-British forces were chiefly engaged in the creation of a bastion about eight miles north of Salonika connecting with the Vardar marshes to the west and the lake defences of Langaza and Beshik to the east and so to the Gulf of Rendina (Orfano) and the Aegean Sea. The area became known as ‘The Birdcage’ on account of the immense quantity of wire used.

In January 1916, the British 80th Brigade, including the 3rd and 4th KRRC Battalions, was posted on the extreme right of the British line at Rendina Gorge on the Gulf of Rendina/Orfano, about forty miles from Salonika, where they were put to work entrenching their position. In due course the Allied Army, reinforced by a reconstituted Serbian Army of 80,000 and Russian and Italian forces, was brought up to a strength of 350,000 men, opposed to whom were 310,000 Germans, Austrians, Bulgars and Turks. Despite this build-up of troops there was very little action over the next four months. The bigger enemy was the weather and malaria.

According to the KRRC men’s diary, they claimed that "...the weather conditions are worse than the enemy itself". During the summer months in the central Struma valley the temperature could reach 118 degrees Fahrenheit. Men fainted in their scores while marching and one young soldier died on the side of the road. Sometimes the rain would reduce the ground to a sea of mud – and with the heat and the rain came the mosquitoes and malaria which took a large toll amongst the soldiers. In 1916/17, of the 300,000 British and French troops based in Salonika, some 120,000 became unfit for active service due to malaria. Allied with other diseases, at one point it reduced the effective strength of the Allied force to 100,000.

The casualties of the Central Powers in the war zone were also dramatic, but reportedly considerably lower: probably due to its forces holding the healthier higher ground, allied with better anti-malarial drug regimens and disease control measures.

On 26 May the perfidious, and still neutral Greeks, handed over to the Bulgarians the Fort at Rupel, a strategic fortification above the deep gorge along which the River Struma led into Bulgaria.

In late July 1916, after preparing Salonika’s defences, the Allies commenced their offensive, advancing to the River Struma and Lake Doiran without opposition and establishing a stable front, holding a line from the Gulf of Rendina on the right to Albania on the Adriatic on the left. The River Men of the 1st Royal Irish Regiment marching into the Struma Valley, June 1916 Vardar divided the British from the French - the British being on the right of the line. The two KRRC Battalions were pushed forward from Rendina Gorge to the unfordable Struma, holding about six miles of the front between Lake Tahinos and the mouth of the Struma on the Gulf of Rendina. The fighting during this phase was not severe, though many casualties were caused by malaria, and it was only patrol work and small mobile columns that kept the troops from stagnating.

It was not until August that shots were first exchanged with the Bulgarians when on 17 August, a joint Bulgarian-German offensive was launched, just three days before a scheduled French offensive. The enemy force in front of the 80th Brigade outnumbered it occasionally, perhaps as much as by ten-to- one. So far as the two KRRC Battalions were concerned, an offensive movement was impossible, but a post on the further bank on the enemy's side of the Struma was occupied by two battalions, one of which was 3/KRRC.

On 23 August, a British column with Major Alexander MacLachlan in command, was tasked with blowing up three bridges over the River Angista, a tributary of the Struma in the vicinity of Kuchuk. The Rhodesian platoon and the remainder of 3/KRRC, commanded by Lieut. Colonel W. J. Long, was in support. The three bridges, despite heavy Bulgarian fire, were successfully blown and the columns withdrew with minimal casualties. The attack achieved early success thanks to surprise, but after two weeks the Allied forces held a defensive line with the B.S.F. taking up positions at Doiran.

THE MONASTIR OFFENSIVE (12 September – November 1916)

Having halted the Bulgarian offensive, the Allies staged a counterattack, the Monastir Offensive, starting on 12 September. The offensive intended to break the deadlock on the Macedonian Front by forcing the capitulation of Bulgaria and relieving the pressure on Romania. The offensive took the shape of a large battle and lasted for three months.

The terrain was rough and the Bulgarians were on the defensive, but the Allied forces made steady gains with the B.S.F. advancing into the Struma Valley to the east. On 30 September, after eighteen days of heavy fighting, the Serbian Drina Division finally captured Kajmakcalan from the exhausted 1st Infantry Brigade of the 3rd Balkan Infantry Division and achieved a breakthrough in the Bulgarian defensive line. A major problem for the Bulgarians was that their army and resources were stretched to the limits from Dobruja to Macedonia and Albania. With the Germans heavily engaged on the Western Front in the Battle of the Somme, Germany could spare few reinforcements. Consequently, Bulgaria turned to the Ottoman Empire which provided some 24,600 men over October-November. With an impending offensive of the Romanian and Russian forces against the Bulgarian Third Army in Dobrudja (situated between the lower Danube River and the Black Sea), General Sarrail planned to use this by coordinating it with a renewed push against the Bulgarian Eleventh Army's ‘Kenali Line’ and eventually knock Bulgaria out of the war. On 4 October the Allies attacked with the French and Russians in the direction of Monastir. The Allies had 103 battalions and 80 batteries against 65 battalions and 57 batteries of the Central Powers. In early October, with the French, Serbian and Russian forces engaged at Montasir, the B.S.F. launched diversionary operations on the River Struma towards Serres. The campaign was successful with the capture of Rupel Pass and advances were made to within a few miles of Serres. It was during this period that a fine piece of work was executed by No.2 “Rhodesian” Platoon, 3/KRRC, commanded at the time by Lieutenant F. D. Fletcher. Headquarters was anxious to capture a prisoner for interrogation purposes and Fletcher with the Rhodesians, who had honed their trench-raiding skills on the Western Front, volunteered for the job. With blackened faces and armed with crude but lethal trench-fighting weapons, the Rhodesians stealthily made it to the enemy trench line and quietly disposed of the sentries. After a sharp fight in the enemy trench and another with an enemy patrol, the raid was swiftly and successfully executed. It was also during this period, on 31 October, that the Rhodesians, with the remainder of 3/KRRC and a Shropshire Light Infantry battalion, took part in a successful holding attack against a whole Turkish Division. Their losses were very small. The Turks, who had relieved the Bulgarians, lost heavily and apparently thought a major attack had been repelled.

After several failed Serbian attacks against the Bulgarian defensive position in the area of the River Crna, the renewed Serbian forces finally crossed the left bank of the river at Brod on 18 October and fortified it. Over the next two weeks the battle raged back and forth with massive casualties suffered by both sides. On 7 November the Serbian artillery started intense fire against the Bulgarian force and after three days Bulgarian losses became so immense that on 10 November it abandoned its positions to the Serbians. Despite the arrival in early November of two more German Divisions to help bolster the Bulgarian Army, the French and Serbian Army captured Kaymakchalan, the highest peak of Nidže mountain, and on 19 November compelled the Central powers to abandon the town of Monastir. The Bulgarians established a new position on the Chervena Stena - Makovo - Gradešnica defensive line. Almost immediately it came under attack but this time the new position held firm because the Allies were exhausted, having reached the limits of their logistical capacity. Thus all French and Serbian attempts to break through the line were defeated and with the onset of winter, the front stabilized along its entire length. On 11 December General Joffre, the French Commander-in-Chief, called off the offensive. An outcome of the Monastir Offensive was the depletion of the Rhodesian Platoon. The fighting had been intense in certain sectors and by January 1917, the veteran No. 2 “Rhodesian” Platoon had dwindled to a mere twenty-six men. The platoon’s Commanding Officer, Lieutenant A. H. Miller wrote: “I suppose there is no chance of reinforcements being sent to us for, if possible, it is our wish to keep the Rhodesian platoon going till the end”.

During 1917, there was comparatively little activity on the British part of the front in Macedonia. In March the two KKRC Battalions, as with the whole British 27th Division, withstood further Bulgarian attacks. The Official History records the Bulgarians using gas for the first time in a bombardment on 17-18 March on British lines between Doiran and the Vardar, and French lines across the river. In the course of three nights they fired about 15 000 asphyxiating shells on a small sector of British trenches, inflicting about 113 casualties, of whom only one died. German and Bulgarian chemical harassment fire, with deadly poison and tear gas, directed mainly against artillery batteries, continued to the end of the war, causing their temporary neutralization. On 22 April the battle for a British breakthrough in the Bulgarian positions began and continued intermittently until 9 May 1917. The assault commenced with a bitter four-day artillery barrage in which the British fired about 100,000 shells. As a result, the earthworks and some wooden structures in the front positions were destroyed. The Bulgarians also opened fire from their batteries between Vardar and Doiran. Bulgarian General Vladimir Vazov ordered fire day and night on the Allied positions. The initial several-hour struggle between the British and Bulgarian batteries was followed by a one-hour Bulgarian counter-barrage in which 10,000 shells were fired.

Two days later, on the night of 24-25 April, the British infantry companies began an attack against the Bulgarian 2nd Brigade and after a bloody fight, managed to take the "Nerezov", "Knyaz Boris" and "Pazardzhik" positions. Bulgarian counter-attacks repulsed the British. The artillery duel continued until 9 May but due to heavy casualties the British had to abandon all attacks. The British lost 12,000 killed, wounded and captured of which more than 2,250 were buried by the Bulgarian defenders.

By April General Sarrail’s army had been reinforced to the point that he had twenty-five divisions: 6 French, 6 Serbian, 7 British, 1 Italian, 3 Greek and 2 Russian. In late April the Allies launched a second major offensive which made little impression on the Bulgarian defences. The main thrust was made by French and Serbian forces to the west while the British launched diversionary attacks at Lake Doiran. The British forces faced some hard fighting. The attacks gained a considerable amount of ground and resisted strong counter-attacks, and any question about the fighting ability of the Bulgarians was dispelled. However, both attacks eventually failed with major losses. After the failed Lake Doiran offensive, the British retreated to their original positions behind the Jumeaux Ravine; the Bulgarians erected banners to tell them ‘We know you are going to the mountains, so are we’. The British action in May triggered a series of attacks elsewhere on the front by the other Allies, known as the Battle of Vardar. The campaign settled down to a stalemate. The offensive was called off on May 21 and the B.S.F. took up a defensive position on the Struma. For the next six months little of major consequence took place.

At the commencement of 1918 the two KRRC Battalions, with the remainder of the 80th Brigade, moved northward to the Struma valley. Here a number of patrol encounters took place and much skill was displayed, particularly by 4/KRRC on 15 and 16 April. By this time the vacillating Greeks had determined to throw in their lot with the Allies and brought up troops by degrees to the amount of about 400,000 men. This of course helped the general situation and enabled the British Government to withdraw some of its battalions to France, where, in view of the successful German advance, their services were badly needed. Among the battalions to be withdrawn was 4/KRRC which returned to the Western Front in the summer of 1918, embarking at Itea on 25th June.

In late June 3/KRRC, with the remainder of the 80th Brigade quit the Struma Valley and after a march of about sixty miles westward took over the position previously held by the French in mountainous country west of the River Vardar. At this point the enemy's shell-fire was heavy and on 1 August the trenches held by 3/KRRC were unsuccessfully attacked. However, partly through malaria and partly by the enemy's shell-fire, 3/KRRC losses had been very heavy, and at the beginning of September it could only muster for fighting purposes about 130 rank and file.

In the middle of September a general advance was begun. The French and Serbians broke through the enemy's line between Monastir and the Vardar, and a day or two later a successful attack was made by British and Greek troops at Doiran, the enemy retreating in disorder. The 80th Brigade was not part of the force engaged but shared in the subsequent pursuit of the enemy. By 21st September the Bulgarians were in full retreat through the Kosturino Pass and on the 22nd September they crossed the frontier into Serbia, but an Armistice with the Bulgarians on the 30th September brought hostilities to a close.

In October 3/KRRC and the Rhodesians marched into Bulgaria. Like a pack of dominoes, Bulgaria then Austria fell and the whole Central Axis began to crumble. The war began in the Balkans and arguably ended there thanks in large part to the supreme efforts of the British forces. By the end of the war, of the original seventy men of No.2 “Rhodesian” Platoon, 3/KRRC that had arrived at Salonika in December 1915, only twelve remained. Fifty-eight Rhodesians died in this harsh and beautiful place where so many soldiers now lie buried in a corner of that foreign field.

______5. TRENCH WARFARE

Trench warfare has become a powerful symbol of the futility of war. Its image is of young men going "over the top" into a hail of fire leading to near-certain death. It is associated with needless slaughter in appalling conditions, combined with the view that brave men went to their deaths because of incompetent and narrow-minded commanders who failed to adapt to the new conditions of trench warfare: class-ridden and backward-looking generals put their faith in the attack, believing superior numbers, morale and dash would overcome the weapons and moral inferiority of the defender. The British and Empire troops on the Western Front were commonly referred to as "lions led by donkeys"10. It has been estimated that up to one third of Allied casualties on the Western Front were incurred in the trenches. For the Allies, life in the trenches was far worse than for the Germans. Often German trenches were even described as comfortable, with electricity, kitchens and beds (Fussell 1977: p. 44). Conversely, Allied trenches (left) were usually temporary in nature, squalid, badly drained and ill supported against cave-in and damage. Where the trenches had been bombed out, the front line sometimes consisted only of shell holes in which the men fought and died. As Fussell describes it, there were usually three lines of trenches: a front-line trench located fifty yards to a mile from its enemy counterpart, guarded by tangled lines of barbed wire; a support trench line several hundred yards back; and a reserve line several hundred yards behind that. A well- built trench did not run straight for any distance, as that would invite the danger of sweeping fire along a long stretch of the line; instead it zigzagged every few yards. There were three different types of trenches: firing trenches, lined on the side facing the enemy by steps where defending soldiers would stand to fire machine guns and throw grenades at the advancing offense; communication trenches; and "saps," shallower positions that extended into no-man’s-land and afforded spots for observation posts, grenade-throwing and machine gun-firing. In total the trenches built during World War I, laid end-to-end, would stretch some 25,000 miles - 12,000 of those miles occupied by the Allies, and the rest by the Central Powers. While the trench system protected the soldiers to a large extent from the worst effects of modern firepower, trench life was horrific. For many veterans the dominant feature of life in the trenches was the problem of trench rats. Rats – big, brown, black and bloated - thrived literally in their millions among trenches in most Fronts of the war. Trench conditions were ideal for rats. Empty food cans were piled in their thousands throughout “No Man's Land”, heaved over the top on a daily basis. Aside from feeding on rotting food in discarded cans, rats would invade dug-outs in search of food and shelter, crawling across the face of sleeping men in the process. McLaughlin (Ragtime Soldiers, p.54) writes: “On the whole...they [the trenches] were fetid holes in which men lived a dank, subterranean existence like constantly endangered moles, sometimes asphyxiated by their braziers or buried alive by shell-fire”.