Brexit and Trade: Implications for Wales

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parliamentary Debates House of Commons Official Report Committees

PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT COMMITTEES Select Committee on the Armed Forces Bill ARMED FORCES BILL Second Sitting Wednesday 31 March 2021 CONTENTS New clauses considered. SCHEDULES 1 TO 5 agreed to. Bill to be reported, without amendment. SCAFB (Bill 244) 2019 - 2021 No proofs can be supplied. Corrections that Members suggest for the final version of the report should be clearly marked in a copy of the report—not telephoned—and must be received in the Editor’s Room, House of Commons, not later than Sunday 4 April 2021 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 47 Select Committee on the 31 MARCH 2021 Armed Forces Bill 48 The Committee consisted of the following Members: Chair: JAMES SUNDERLAND † Anderson, Stuart (Wolverhampton South West) † Holden, Mr Richard (North West Durham) (Con) (Con) † Jones, Mr Kevan (North Durham) (Lab) † Antoniazzi, Tonia (Gower) (Lab) † Lopresti, Jack (Filton and Bradley Stoke) (Con) † Carden, Dan (Liverpool, Walton) (Lab) † Mercer, Johnny (Minister for Defence People and † Dines, Miss Sarah (Derbyshire Dales) (Con) Veterans) † Monaghan, Carol (Glasgow North West) (SNP) † Docherty, Leo (Aldershot) (Con) † Morgan, Stephen (Portsmouth South) (Lab) † Docherty-Hughes, Martin (West Dunbartonshire) † Wheeler, Mrs Heather (South Derbyshire) (Con) (SNP) † Henry, Darren (Broxtowe) (Con) Yohanna Sallberg, Matthew Congreve, Committee Clerks † Hodgson, Mrs Sharon (Washington and Sunderland West) (Lab) † attended the Committee 49 Select Committee on the HOUSE OF COMMONS Armed Forces Bill 50 The Chair: With this it will be convenient to discuss Select Committee on the new clause 19— Armed Forces Federation— Armed Forces Bill “(1) The Armed Forces Act 2006 is amended as follows. -

General Election 2019: Mps in Wales

Etholiad Cyffredinol 2019: Aelodau Seneddol yng Nghymru General Election 2019: MPs in Wales 1 Plaid Cymru (4) 5 6 Hywel Williams 2 Arfon 7 Liz Saville Roberts 2 10 Dwyfor Meirionnydd 3 4 Ben Lake 8 12 Ceredigion Jonathan Edwards 14 Dwyrain Caerfyrddin a Dinefwr / Carmarthen East and Dinefwr 9 10 Ceidwadwyr / Conservatives (14) Virginia Crosbie Fay Jones 1 Ynys Môn 13 Brycheiniog a Sir Faesyfed / Brecon and Radnorshire Robin Millar 3 Aberconwy Stephen Crabb 15 11 Preseli Sir Benfro / Preseli Pembrokeshire David Jones 4 Gorllewin Clwyd / Clwyd West Simon Hart 16 Gorllewin Caerfyrddin a De Sir Benfro / James Davies Carmarthen West and South Pembrokeshire 5 Dyffryn Clwyd / Vale of Clwyd David Davies Rob Roberts 25 6 Mynwy / Monmouth Delyn Jamie Wallis Sarah Atherton 33 8 Pen-y-bont ar Ogwr / Bridgend Wrecsam / Wrexham Alun Cairns 34 Simon Baynes Bro Morgannwg / Vale of Glamorgan 9 12 De Clwyd / Clwyd South 13 Craig Williams 11 Sir Drefaldwyn / Montgomeryshire 14 15 16 25 24 17 23 21 22 26 18 20 30 27 19 32 28 31 29 39 40 36 33 Llafur / Labour (22) 35 37 Mark Tami 38 7 34 Alyn & Deeside / Alun a Glannau Dyfrdwy Nia Griffith Gerald Jones 17 23 Llanelli Merthyr Tudful a Rhymni / Merthyr Tydfil & Rhymney Tonia Antoniazzi Nick Smith Chris Bryant 18 24 30 Gwyr / Gower Blaenau Gwent Rhondda Geraint Davies Nick Thomas-Symonds Chris Elmore Jo Stevens 19 26 31 37 Gorllewin Abertawe / Swansea West Tor-faen / Torfaen Ogwr / Ogmore Canol Caerdydd / Cardiff Central Carolyn Harris Chris Evans Stephen Kinnock Stephen Doughty 20 27 32 38 Dwyrain Abertawe / -

THE 422 Mps WHO BACKED the MOTION Conservative 1. Bim

THE 422 MPs WHO BACKED THE MOTION Conservative 1. Bim Afolami 2. Peter Aldous 3. Edward Argar 4. Victoria Atkins 5. Harriett Baldwin 6. Steve Barclay 7. Henry Bellingham 8. Guto Bebb 9. Richard Benyon 10. Paul Beresford 11. Peter Bottomley 12. Andrew Bowie 13. Karen Bradley 14. Steve Brine 15. James Brokenshire 16. Robert Buckland 17. Alex Burghart 18. Alistair Burt 19. Alun Cairns 20. James Cartlidge 21. Alex Chalk 22. Jo Churchill 23. Greg Clark 24. Colin Clark 25. Ken Clarke 26. James Cleverly 27. Thérèse Coffey 28. Alberto Costa 29. Glyn Davies 30. Jonathan Djanogly 31. Leo Docherty 32. Oliver Dowden 33. David Duguid 34. Alan Duncan 35. Philip Dunne 36. Michael Ellis 37. Tobias Ellwood 38. Mark Field 39. Vicky Ford 40. Kevin Foster 41. Lucy Frazer 42. George Freeman 43. Mike Freer 44. Mark Garnier 45. David Gauke 46. Nick Gibb 47. John Glen 48. Robert Goodwill 49. Michael Gove 50. Luke Graham 51. Richard Graham 52. Bill Grant 53. Helen Grant 54. Damian Green 55. Justine Greening 56. Dominic Grieve 57. Sam Gyimah 58. Kirstene Hair 59. Luke Hall 60. Philip Hammond 61. Stephen Hammond 62. Matt Hancock 63. Richard Harrington 64. Simon Hart 65. Oliver Heald 66. Peter Heaton-Jones 67. Damian Hinds 68. Simon Hoare 69. George Hollingbery 70. Kevin Hollinrake 71. Nigel Huddleston 72. Jeremy Hunt 73. Nick Hurd 74. Alister Jack (Teller) 75. Margot James 76. Sajid Javid 77. Robert Jenrick 78. Jo Johnson 79. Andrew Jones 80. Gillian Keegan 81. Seema Kennedy 82. Stephen Kerr 83. Mark Lancaster 84. -

Petition As Lodged

UNTO THE RIGHT HONOURABLE LORDS OF COUNCIL AND SESSION P E T I T I O N of (FIRST) JOANNA CHERRY QC MP, House of Commons, London SW1A 0AA (SECOND) JOLYON MAUGHAM QC, Devereux Chambers, Devereux Court, London WC2R 3JH (THIRD) JOANNE SWINSON MP, House of Commons, London SW1A 0AA (FOURTH) IAN MURRAY MP, House of Commons, London SW1A 0AA (FIFTH) GERAINT DAVIES MP, House of Commons, London SW1A 0AA (SIXTH) HYWEL WILLIAMS MP, House of Commons, London SW1A 0AA (SEVENTH) HEIDI ALLEN MP, House of Commons, London SW1A 0AA (EIGHTH) ANGELA SMITH MP, House of Commons, London SW1A 0AA (NINTH) THE RT HON PETER HAIN, THE LORD HAIN OF NEATH, House of Lords, London SW1A 0PW (TENTH) JENNIFER JONES, THE BARONESS JONES OF MOULESCOOMB, House of Lords, London SW1A 0PW (ELEVENTH) THE RT HON JANET ROYALL, THE BARONESS ROYALL OF BLAISDON, House of Lords, London SW1A 0PW (TWELFTH) ROBERT WINSTON, THE LORD WINSTON OF HAMMERSMITH, House of Lords, London SW1A 0PW (THIRTEENTH) STEWART WOOD, THE LORD WOOD OF ANFIELD, House of Lords, London SW1A 0PW (FOURTEENTH) DEBBIE ABRAHAMS MP, House of Commons, London SW1A 0AA (FIFTEENTH) RUSHANARA ALI MP, House of Commons, London SW1A 0AA (SIXTEENTH) TONIA ANTONIAZZI MP, House of Commons, London SW1A 0AA (SEVENTEENTH) HANNAH BARDELL MP, House of Commons, London SW1A 0AA (EIGHTEENTH) DR ROBERTA BLACKMAN-WOODS MP, House of Commons, London SW1A 0AA (NINETEENTH) BEN BRADSHAW MP, House of Commons, London SW1A 0AA (TWENTIETH) THE RT HON TOM BRAKE MP, House of Commons, London SW1A 0AA (TWENTY-FIRST) KAREN BUCK MP, House of Commons, London -

Labour Party General Election 2017 Report Labour Party General Election 2017 Report

FOR THE MANY NOT THE FEW LABOUR PARTY GENERAL ELECTION 2017 REPORT LABOUR PARTY GENERAL ELECTION 2017 REPORT Page 7 Contents 1. Introduction from Jeremy Corbyn 07 2. General Election 2017: Results 11 3. General Election 2017: Labour’s message and campaign strategy 15 3.1 Campaign Strategy and Key Messages 16 3.2 Supporting the Ground Campaign 20 3.3 Campaigning with Women 21 3.4 Campaigning with Faith, Ethnic Minority Communities 22 3.5 Campaigning with Youth, First-time Voters and Students 23 3.6 Campaigning with Trade Unions and Affiliates 25 4. General Election 2017: the campaign 27 4.1 Manifesto and campaign documents 28 4.2 Leader’s Tour 30 4.3 Deputy Leader’s Tour 32 4.4 Party Election Broadcasts 34 4.5 Briefing and Information 36 4.6 Responding to Our Opponents 38 4.7 Press and Broadcasting 40 4.8 Digital 43 4.9 New Campaign Technology 46 4.10 Development and Fundraising 48 4.11 Nations and Regions Overview 49 4.12 Scotland 50 4.13 Wales 52 4.14 Regional Directors Reports 54 4.15 Events 64 4.16 Key Campaigners Unit 65 4.17 Endorsers 67 4.18 Constitutional and Legal services 68 5. Labour candidates 69 General Election 2017 Report Page 9 1. INTRODUCTION 2017 General Election Report Page 10 1. INTRODUCTION Foreword I’d like to thank all the candidates, party members, trade unions and supporters who worked so hard to achieve the result we did. The Conservatives called the snap election in order to increase their mandate. -

Aelodau Seneddol Yng Nghymru General Election 2017: Mps in Wales

Etholiad Cyffredinol 2017: Aelodau Seneddol yng Nghymru General Election 2017: MPs in Wales 1 Plaid Cymru (4) Hywel Williams 5 6 2 Arfon Liz Saville-Roberts 7 10 2 3 Dwyfor Meirionnydd 4 Ben Lake 12 8 Ceredigion Jonathan Edwards 14 Dwyrain Caerfyrddin a Dinefwr / Carmarthen East and Dinefwr 9 10 Ceidwadwyr / Conservatives (8) Guto Bebb 3 Aberconwy David Jones 4 Gorllewin Clwyd / Clwyd West 11 Glyn Davies 11 Sir Drefaldwyn / Montgomeryshire Chris Davies 13 Brycheiniog a Sir Faesyfed / Brecon and Radnorshire Stephen Crabb 15 Preseli Sir Benfro / Preseli Pembrokeshire Simon Hart 16 Gorllewin Caerfyrddin a De Sir Benfro / Carmarthen West and South Pembrokeshire David T. C. Davies 25 12 Mynwy / Monmouth Alun Cairns 34 Bro Morgannwg / Vale of Glamorgan 13 14 15 16 24 25 17 23 21 22 26 Llafur / Labour (28) 18 20 30 27 Albert Owen 1 19 32 Ynys Môn 28 31 Chris Ruane 29 39 40 5 Dyffryn Clwyd / Vale of Clwyd 36 33 35 37 David Hanson Carolyn Harris Wayne David 6 20 28 38 Delyn Dwyrain Abertawe / Swansea East Caerffili / Caerphilly 34 Mark Tami Christina Rees Owen Smith 7 21 29 Alyn & Deeside / Alun a Glannau Dyfrdwy Castell-nedd / Neath Pontypridd Ian Lucas Ann Clywd Chris Bryant Anna McMorrin 8 22 30 36 Wrecsam / Wrexham Cwm Cynon / Cynon Valley Rhondda Gogledd Caerdydd / Cardiff North Susan Jones Gerald Jones Chris Elmore Jo Stevens 9 23 31 37 De Clwyd / Clwyd South Merthyr Tudful a Rhymni / Merthyr Tydfil & Rhymney Ogwr / Ogmore Canol Caerdydd / Cardiff Central Nia Griffith Nick Smith Stephen Kinnock Stephen Doughty 17 24 32 38 Llanelli Blaenau -

Global Centre of Rail Excellence in Wales Newsletter: November 2019

Global Centre of Rail Excellence UPDATE: NOVEMBER/DECEMBER 2019 Welsh Government is working in partnership with Neath Port Talbot and Powys Councils to develop proposals for a Global Centre of Rail THIS UPDATE Excellence (GCRE) on the site of the Nant Helen open cast mine and Onllwyn coal washery site at the head of the Dulais and Tawe Valleys. Ensuring excellence The proposals form an important addition to the site’s restoration Project briefing and strategy brought forward by Celtic Energy and will act as a driver for early engagement rail industry innovation, investment and growth in Wales, the wider UK and internationally. Key politicians back plans There has been a great deal of support and enthusiasm for the project EIA scoping submitted and we are continuing to develop the business case and move forward with plans to submit a planning application in early 2020. Next steps Establishing the business case As part of the business case As part of this process, we have development for the project, we carried established a Project Evaluation Group out extensive ‘soft-market-testing’ (PEG), which consists of a range of with rail industry stakeholders earlier senior rail industry leaders who are this year. This allowed us to examine examining work undertaken on the the business need and incorporate project to date, analysing project technical advice and feedback into viability and assessing the best way an initial masterplan design. We are forward. continuing to discuss our emerging This exercise is an important milestone plans with the rail industry as we seek in the evolution of the GCRE project, to establish a viable, sustainable and which is expected to be concluded investable project that can proceed early in the new year and will inform from discussion and design to delivery. -

17 April 2020 Page 1 of 4 by Email Only Rebecca Evans AM Minister

17 April 2020 page 1 of 4 By email only Rebecca Evans AM Minister for Finance and Trefnydd [email protected] Ken Skates AM Minister for Economy, Transport and North Wales [email protected] Dear Ministers, Ms Evans AM and Mr Skates AM Dental practices and critical need for business support We need to bring to your attention the precarious position of many dental practices operating in Wales that have lost substantial private income sources overnight since all routine dentistry was halted from mid-March in response to COVID-19. Dental practices are independent businesses and are exposed to many of the same financial conditions that other types of businesses have faced with lockdown, but without the same eligibility for government support. The new Economic Resilience Fund in Wales launching today is unlikely to help many practices because the scheme is clearly aimed at businesses with employees rather than contractors. Most dentists in General Dentistry in England and Wales are contractors not employees. The same is true for dental therapists and hygienists. Moreover, many dentists have been personally financially exposed due to lack of any support for their private income loss, if normally earning over £50K. While the Minister for Health and Social Services has acted promptly to put in place a financial support scheme for General Dental Practices, the support is only with respect to the NHS component of contract income and then only at 80% of normal contract value for the duration of the COVID-19 lockdown measures. At the same time practices are required to pay their staff 100% of their NHS earnings. -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Monday Volume 687 18 January 2021 No. 161 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Monday 18 January 2021 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2021 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 601 18 JANUARY 2021 602 David Linden [V]: Under the Horizon 2020 programme, House of Commons the UK consistently received more money out than it put in. Under the terms of this agreement, the UK is set to receive no more than it contributes. While universities Monday 18 January 2021 in Scotland were relieved to see a commitment to Horizon Europe in the joint agreement, what additional funding The House met at half-past Two o’clock will the Secretary of State make available to ensure that our overall level of research funding is maintained? PRAYERS Gavin Williamson: As the hon. Gentleman will be aware, the Government have been very clear in our [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] commitment to research. The Prime Minister has stated Virtual participation in proceedings commenced time and time again that our investment in research is (Orders, 4 June and 30 December 2020). absolutely there, ensuring that we deliver Britain as a [NB: [V] denotes a Member participating virtually.] global scientific superpower. That is why more money has been going into research, and universities will continue to play an incredibly important role in that, but as he Oral Answers to Questions will be aware, the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy manages the research element that goes into the funding of universities. -

The Green Challenges to Come

NEW GROUND AUTUMN 2017 Campaigning for environmental change & social justice THE GREEN CHALLENGES TO COME G R W O U E N N D CONFERENCE 2017 A U 7 T 0 1 U M N 2 Sadiq Khan My Vision for a Greener London Chi Onwurah MP Jacinda Ardern Growing a New Zealand’s sustainable future Climate Opportunity Welcome to our 2017 Autumn Edition NEWS ANDREW PAKES & ADAM DYSTER What a difference a few months can issues where Labour can make a real It’s BEEN A BUSY FEW MONTHS FOR make. Little did any of us expect that difference in this new political context. SERA within days of the last edition landing SERA - HERE ARE JUST A FEW HIGHLIGHTS on people’s doorsteps, we’d be gearing The biggest of course will continue to up to fight a snap general election. be Brexit, and both Baroness Young and NEWS OF WHAT WE’vE BEEN UP TO. Mary Creagh MP look at some of the Whilst the final result may not have been challenges of the Repeal Bill, and the the one we were fighting for - and the UK worrying threats the current Tory plans will have to continue to endure Theresa pose to our environmental protections. May’s premiership, now propped up by As part of Andy Burnham’s ‘Our policy first announced at the SERA the DUP - it was fantastic to see so many The new Fisheries and Agriculture bills ANDY BURNHAM Manifesto’ process, SERA held a manifesto event. The Summit will of Labour’s environmental champions will also be key for the future of our elected and re-elected to Parliament. -

Publication of the Law Commission’S Recommendations, and That Draft Must Be in a Form Which Would Implement All Those Recommendations

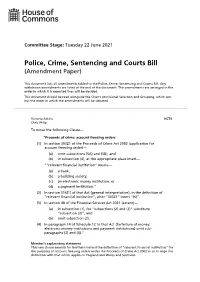

Committee Stage: Tuesday 22 June 2021 Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill (Amendment Paper) This document lists all amendments tabled to the Police, Crime, Sentencing and Courts Bill. Any withdrawn amendments are listed at the end of the document. The amendments are arranged in the order in which it is expected they will be decided. This document should be read alongside the Chair’s provisional Selection and Grouping, which sets out the order in which the amendments will be debated. Victoria Atkins NC74 Chris Philp To move the following Clause— “Proceeds of crime: account freezing orders (1) In section 303Z1 of the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 (application for account freezing order)— (a) omit subsections (5A) and (5B), and (b) in subsection (6), at the appropriate place insert— ““relevant financial institution” means— (a) a bank, (b) a building society, (c) an electronic money institution, or (d) a payment institution.” (2) In section 316(1) of that Act (general interpretation), in the definition of “relevant financial institution”, after “303Z1” insert “(6)”. (3) In section 48 of the Financial Services Act 2021 (extent)— (a) in subsection (1), for “subsections (2) and (3)” substitute “subsection (2)”, and (b) omit subsection (3). (4) In paragraph 14 of Schedule 12 to that Act (forfeiture of money: electronic money institutions and payment institutions) omit sub- paragraphs (3) and (4).” Member’s explanatory statement This new clause amends for Northern Ireland the definition of “relevant financial institution” for the purposes of account freezing orders under the Proceeds of Crime Act 2002 so as to align the definition with that which applies in England and Wales and Scotland. -

Formal Minutes of the Committee

House of Commons Welsh Affairs Committee Formal Minutes of the Committee Session 2017-19 TUESDAY 12 SEPTEMBER 2017 Members present: David T. C. Davies, in the Chair1 Chris Davies Paul Flynn Geraint Davies Ben Lake Glyn Davies 1. Declaration of interests Members declared their interests in accordance with the Resolution of the House of 13 July 1992 (see Appendix). 2. Committee working methods The Committee considered this matter. Ordered, That the public be admitted during the examination of witnesses unless the Committee orders otherwise. Resolved, That witnesses who submit written evidence to the Committee are authorised to publish it on their own account in accordance with Standing Order No. 135, subject always to the discretion of the Chair or where the Committee orders otherwise. Resolved, That the Committee approves the use of electronic equipment by Members during public and private meetings, provided that they are used in accordance with the rules and customs of the House. Resolved, That the Committee shall not consider individual cases. The Committee noted the formal rules relating to the confidentiality of Committee papers. 3. Future programme The Committee considered this matter. Resolved, That the Committee inquire into Brexit: agriculture, trade and the repatriation of powers. Resolved, That the Committee inquire into The cancellation of rail electrification in South Wales. Resolved, That the Committee take oral evidence from the Secretary of State for Wales and the UK Government Minister for Wales, on their responsibilities. [Adjourned till Tuesday 10 October at 4.00 pm 1 David T.C. Davies was elected as the Chair of the Committee on 12 July 2017, in accordance with Standing Order No.