VCI/ELLISON EQUIPMENT—COORDINATED GLOBAL SOURCING ACROSS CONTINENTS

VCI/Ellison, which represents the consolidation of the heavy transportation equipment units of two previously separate and regional companies, is facing worldwide pricing pressures from customers and competitors. The ability to meet financial targets has presented a major challenge for this new global company. With limited ability to raise product prices, the alternatives facing VCI/Ellison have become managing material costs better or absorbing price increases through lower profit margins and profitability.

Given that direct materials represent over 70% of the company’s total costs, it becomes easy to appreciate the impact that improved global sourcing efforts should have on profitability.

From the time VCI, a European company, assumed ownership of U.S.-based

Ellison both companies have sought to leverage the commonality between them on a global basis. The company concluded early on that procurement offered excellent opportunities for global synergy across the two continents. Ellison Equipment, working with VCI, has implemented a multi-step global sourcing process designed to leverage the volumes available through the newly combined units. This case offers insight into how two geographically and culturally diverse companies, brought together through acquisition, are attempting to gain synergy and efficiency through integrated global sourcing. The challenges facing this global effort include not only geographic separation, but also cultural, language, technical, and business practice differences.

Global Sourcing Process Overview The global process at this company features two teams, one at Ellison Equipment and one at VCI, working concurrently on the same global project. While Ellison had experience using cost reduction teams, VCI had never used teams within their procurement or engineering areas. As part of this process teams are aligned on both sides of the ocean working jointly on a commodity category or project. The teams eventually work face-to-face as they progress through the process steps.

Each global sourcing project has an expected duration of six months (although the transition to a new supplier can take much longer). After working with an external consultant to segment its primary products into six commodity groups, VCI and Ellison jointly identified 27 project opportunities. This process is designed to support nine projects at a time (each having a six-month duration) with three iterations or waves.

Each team pursues three categories of commodities (which may have sub-categories or sub-commodities) simultaneously, so three teams in a wave pursue a total of nine projects.

VCI/Ellison has also decided to apply its global process to contracts that the sourcing teams determine are regional rather than global (a region is defined as North

America or Europe only). A global supplier is one that can competitively supply a product or service to all of VCI/Ellison’s worldwide production and assembly locations.

To date a majority of contracts have been classified as regional. This is not surprising given the fact that the major competitors in the heavy equipment industry operate regionally, which the supply community is structured to support.

VCI/Ellison’s Global Sourcing Process With the help of an external consultant

VCI/Ellison has created a rigorous and thorough nine-step global strategy development and implementation process. Steps 1-4 of this process involve strategy development, while Steps 5-8 involve strategy implementation. Global sourcing project teams are responsible for the first four steps. Step 0 involves the executive steering committee selecting nine global sourcing projects at a time (called a wave) and identifying the cost savings expected from each project.

Perhaps the most important task associated with Step 1, which is project launch, is the formation of the global sourcing teams. Team members are selected based on their familiarity with the commodity or items under review. Since there is usually only one engineer and buyer for the commodity, these individuals become team members almost by default.

The team leader works with the team to develop time schedules, a list of deliverables, and expected milestones within the six-month project window. During this part of the process the teams begin to quantify what they are studying by collecting and validating data. Across each category there may be four or five segments or sub- categories that require separate analysis. While each team decides on the segmentation of a category, both teams assigned to the project must agree on the segmentation.

Even thought each project technically has two teams assigned (one at each company working simultaneously), they are really one team looking at the same project.

Teams can proceed to the next process step without the explicit approval of the executive steering committee. However, teams are required to publish progress updates weekly. A major responsibility of the business analyst (discussed later) is to compile and provide performance updates to the executive steering committee.

Some managers consider Step 2, sourcing strategy development, to be the most interesting and critical part of the global process. During this step the project teams identify potential worldwide suppliers. One of the realizations when beginning this process was that supplier switching, including switching from long-established suppliers, was likely to occur. This realization was based partly on the external consultant’s global sourcing experience. Supplier switching can be time-consuming and difficult as new supply chain relationships are established.

From the list of potential suppliers, the teams send Requests for Information

(RFIs), which they can modify to meet the specific needs of their category or segment.

The RFI is a generic supplier questionnaire that introduces the global process and requests data about sales, production capacity, quality certification (such as ISO 9000), familiarity with the equipment industry, and major customers. It is not unusual to send

400-500 RFIs during a project, depending on the complexity of the category and segments the team is working.

The RFI is a first filter in the supplier selection process. During this step it is critical that suppliers return a high percentage of the RFIs, which are separated and reported by region of the world. Of the 400-500 RFIs forwarded to suppliers, a team may receive and analyze several hundred completed RFIs. The teams also conduct a detailed supply market analysis to develop a thorough understanding of the economics and dynamics of a particular market.

Step 2 is usually the first time that the two teams working on a global sourcing project meet face to face. The European and U.S. teams meet physically to conduct face to face analysis of the RFIs returned by suppliers. It is each team’s responsibility to establish the criteria for determining which suppliers will receive Requests for Proposals

(RFPs). A key decision during Step 2 is whether a procurement opportunity appears to be regional versus global. A lack of globally capable suppliers can make a project a regional opportunity.

Step 2 requires a major effort on the part of engineering. Engineers on both sides will examine drawings in an effort to commonize part specifications between locations. While a project team may conclude that a global supply source does not exist, there may be opportunities to commonize or standardize specifications across the two locations. Step 3, requests for proposals, features the development, sending, and analysis of formal proposals to the most promising suppliers identified in Step 2. The average number of proposals forwarded to suppliers per project is 20-30. Suppliers typically require six weeks to analyze and return the RFPs. The teams strive for a high percentage of returned proposals, similar to the RFIs. Team leaders, representing the project teams, report RFP progress to the executive steering committee at a weekly meeting.

Teams are responsible for analyzing the returned supplier proposals. Like the

RFIs, teams can set their own evaluation criteria and weights, but members must reach consensus in their choices. The proposal allows suppliers to provide design suggestions.

The teams usually meet via video or audio conferencing to review the proposals.

Engineers again take a lead role in evaluating technical merits. Complex purchase requirements may require teams to meet face-to-face for a second time. Using standardized spreadsheet tools that are available to all teams, each team analyzes its proposals and decides, based on the analysis, which suppliers will be invited to negotiations.

A negotiation workshop takes place at VCI’s European learning center during this step. This session has several objectives—team members receive training in negotiation, the project teams develop their negotiating strategy, and the teams select a negotiation leader. If a team determined that a sourcing opportunity was regional, negotiation will occur separately by region. Teams select regional negotiation leaders if the project is a regional opportunity or a single negotiator if the project is global. The decision of who should be the negotiating leader is based on discussion and consensus rather than voting. Of the first 27 projects, fully one-third of the negotiating leaders were selected from outside the project teams. Step 4 involves recommending a strategy and negotiating with selected suppliers. Project teams make a recommendation to an executive committee, specifically the vice presidents of purchasing and engineering from VCI and Ellison. The executive committee may ask questions but to date has not overturned any team recommendations. Team recommendations include the selected supplier(s) with expected savings and timings identified. The teams also identify whether the suppliers are regional or global but do not recommend contract length.

In this step the negotiating team probes and discusses in-depth the proposals submitted by suppliers. Suppliers can be disqualified if engineering determines the supplier cannot satisfy technical requirements, or the team is not satisfied with the commercial issues

All negotiation in Step 4 is conducted face to face with suppliers at VCI/Ellison sites. Half the negotiations so far have occurred in the U.S. and half in Europe. Before suppliers arrive they receive feedback concerning the competitiveness of their proposal, which they are allowed to revise before negotiations commence. Suppliers may be excused if they are informed that they are not competitive and choose not to revise their proposal. Once the lead negotiator takes over, the team leader’s role begins to diminish

(unless the team leader is also the lead negotiator). The team leader usually remains as part of the negotiating team.

Step 5, called supplier certification, features purchasing and engineering groups receiving the team’s recommendation and preliminary terms of the negotiated agreement. At this time functional directors will begin to budget expected savings from the proposed contract into their financial projections. Supplier site visits can occur during this step by representatives of the functional groups. For example, engineering, procurement, and quality assurance may want to validate a number of topics during this step. The time frame for this step varies from one month to over a year. Step 6, finalizing the contract, involves crafting the final contract based on the outcome of the negotiations. The negotiation leader remains with the process until the contract is complete. While the legal department is also involved, a buyer writes the contract using an agreement template. Contracts are typically three years in duration.

Both sides of the ocean are involved in formalizing the contract if the agreement is global rather than regional.

Global agreements differ from traditional contracts. They include productivity improvement requirements to offset material increases. The agreements also encourage technical advancements by the supplier to further reduce material costs or enhance product performance. This process also includes a formal process to manage improvements, whereas the process for previous or non-global agreements has been informal. And, in a somewhat significant departure from previous contracting practices, incentives such as 50/50 improvement sharing are starting to appear.

Step 7, sample testing and approval, assesses the samples provided by the selected supplier. Production facilities go through a production readiness stage, initial sample inspection reports are developed, parts are checked off of production tooling, and the negotiation leader develops a production rollout plan with help from his or her counterpart on the other side of the ocean.

Step 8, the concluding step of a global project, is the production readiness stage.

The selected supplier may send a day or weeks worth of supply to be used in actual production. Logistics becomes part of the implementation team if there is a switch from one supplier to another.

Organizational Enablers VCI/Ellison has put in place certain enablers that support global sourcing. This includes the formation of an executive steering committee, the use of global teams, formally selected team leaders, and the creation of a business analyst’s position to support the operational and analytical needs of the teams. An executive steering committee at each unit reviews and prioritizes projects for study. A sourcing director at VCI and a counterpart at Ellison drive the process at both organizations. Working jointly, these executives recommend projects for study, solicit input from functional areas in terms of cost savings and quality improvement opportunities, develop a plan to pursue the project (including assembling a cross- functional team), track the status of each project through weekly progress updates, and manage the global process to ensure its continued success. The executive steering committee members conduct a video conferencing meeting each week for two hours.

This meeting also involves team leaders for projects that are in process.

Cross-functional teams are an integral part of this process. Two teams, one from

VCI and one from Ellison, work simultaneously on the same sourcing opportunity, each with a formal team leader, two functional members (usually from engineering and purchasing), and a business analyst that supports both teams. Each project consists of seven combined positions across two teams. The team leader and business analyst are full-time assignments while the buyer and engineer provide a part-time commitment.

Teams are responsible only for the first four steps of the global sourcing process.

The two teams usually come together physically two or three times over a project’s duration. Both sides agree, however, that face to face interaction is time consuming. At the conclusion of each project the teams are required to write a “white book” documenting the lessons learned from their experience.

With any team-based approach the role of the team leader is critical to success.

Project leaders are responsible for planning team meetings, which are held once or twice a week depending on the phase of the project, and reporting project status to the executive steering committee. Planning includes setting the meeting agenda, ensuring the global process steps are followed, and working with team members to meet time lines and achieve project goals. The leader also communicates with each member’s management when necessary to ensure commitment. Agreement is widespread that the team leader is a critical part of the process, particularly when the leader must work with members to balance their priorities while still challenging the team to achieve demanding performance improvement targets.

Each set of teams that works on three projects simultaneously has a business analyst assigned to support the effort. The time required for managing requests for information (RFIs) and requests for proposals (RFPs) across two continents is extensive.

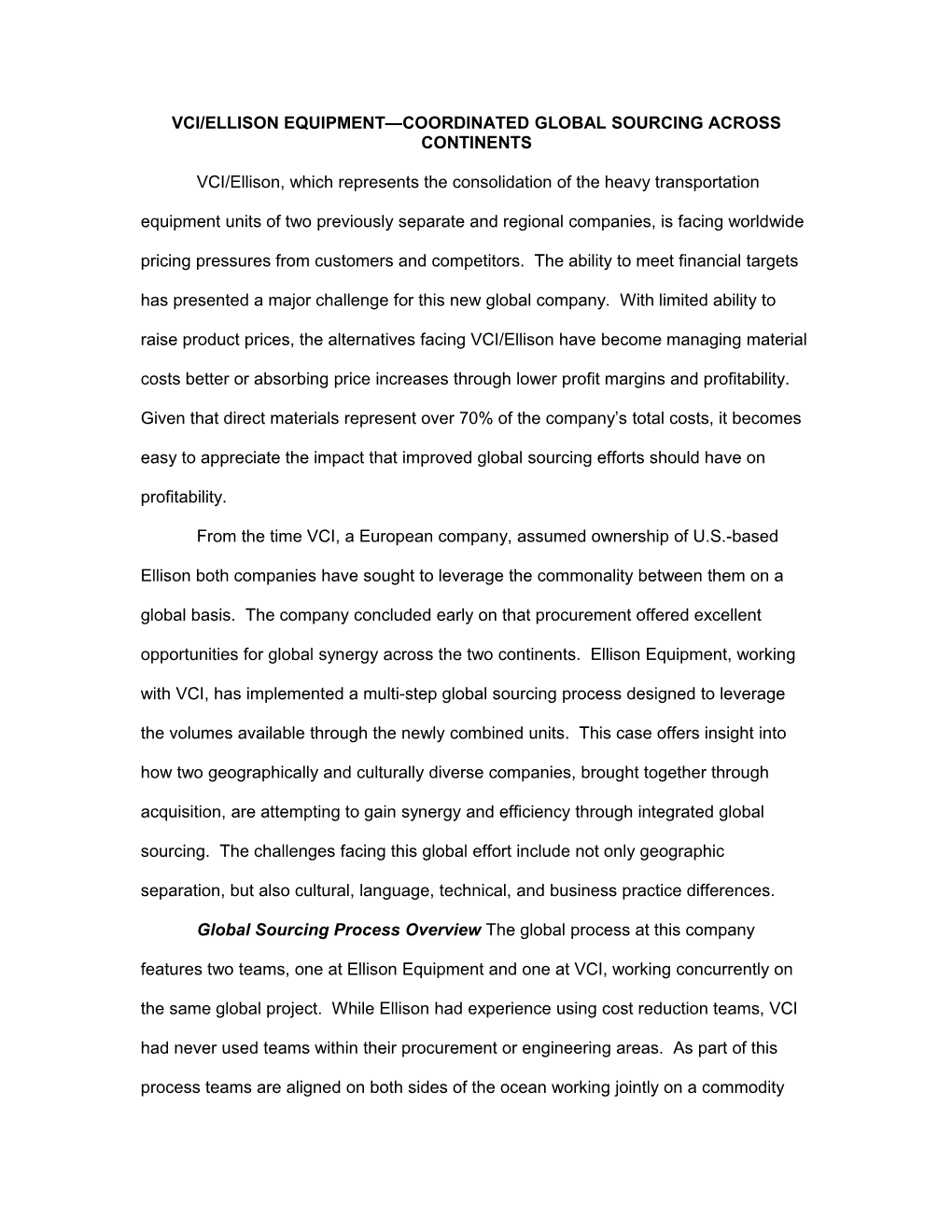

VCI/Ellison created a full-time business analyst position to manage the required tasks when pursuing global agreement. Exhibit 1 outlines the key features of this position.

The analyst is central to the success of the RFI and RFP process. Analysts compile and send RFI and RFP packages to suppliers, track and report response rates, input RFI and RFP response information into a sourcing software system and database, and follow-up with suppliers who are late with their submission. The business analyst also answers any questions that suppliers have or forwards their inquiries to the appropriate procurement or engineering representative. The analyst also provides feedback to suppliers concerning the competitiveness of their initial quotation or proposal. Finally, analysts have responsibility for forwarding the project database to their counterpart team across the ocean on a regular basis. Team members are relieved of extensive analytic and clerical duties, which allows members to commit time to value- adding activities.

While management views the business analyst position as an ideal way for high- potential individuals to gain exposure to purchasing and sourcing, there are some issues with this part of the process. Managing three projects simultaneously creates an intense work pace that affects morale and promotes turnover. Furthermore, one analyst maintained that too many RFPs are forwarded to suppliers, resulting in an intensive work requirement. Obtaining the necessary drawings from engineering is also a time consuming activity. Finally, the process to coordinate team activities between the U.S. and Europe presents some difficulties. The analyst must fax documents daily, manage reams of paper, and use software that was not compatible between the U.S. and

European systems.

Global Sourcing Outcomes A number of themes emerge when managers describe the value of taking an integrated approach to worldwide sourcing. Perhaps most importantly, global sourcing was the first major integrative effort undertaken between VCI and Ellison. This process demonstrated that the two organizations could work jointly to capture the benefits offered by taking a global rather than regional perspective, although the company is somewhat disappointed by the number of opportunities that were determined to be regional rather than global. Second, this process demonstrated that material savings are available from a disciplined approach to worldwide sourcing. Contracts resulting from this process average over 10% in material price savings, which is not as high as the savings that Santek is realizing. Part of this is due to the fact that many of VCI/Ellison’s agreements are regional rather than global.

Global sourcing has also narrowed the differences between Ellison’s and VCI’s sourcing practices. Ellison has historically been more relationship focused with suppliers and viewed negotiation as a means to build upon those relationships. VCI has shown a greater willingness to switch suppliers more frequently and faster due to cost and quality considerations. The global process has enabled the two companies to converge on a consistent sourcing approach that combines the best features of both sourcing philosophies.

A repeated sentiment among managers is that this nine-step process introduced a discipline to sourcing at VCI/Ellison. Each sourcing project moves lock-step over a six- month period with weekly reporting to an executive steering committee. Global sourcing teams must meet deadlines and milestones, make sure information gets to suppliers, and thoroughly research the supply base before negotiating and awarding contracts.

The process has made everything “official” with suppliers, who have taken VCI/Ellison’s global efforts seriously.

The process is not without less positive outcomes or observations. One issue concerns a lack of knowledge between VCI and Ellison personnel about each other’s supply base. As a result, each side during a project has had a natural tendency to favor its own suppliers. When the two project teams work together face-to-face, they have to spend time sorting out who the best suppliers from each side are globally. This “home market bias” has hindered the process to some degree. Global sourcing teams have been forced to learn more about each other’s suppliers, which requires greater effort and an open mind.

As expected, all 27 global project teams to date have not been equally effective.

One team leader argues that any differences in performance are due to the quality and effort of the team members and leaders rather than project complexity. This highlights the need for careful member evaluation and selection. Unfortunately, team leaders do not receive special training before they assume that critical position. And, team members are usually selected because they are most familiar with the item or category under study rather than their ability to be effective team members.

While external consultants played a critical and highly visible role in developing and using VCI/Ellison’s global process, managers point out that the use of consultants caused some concern. For example, consultants assumed the role of team leader with several early teams, raising questions concerning who should lead the teams and their qualifications. The consultants often dictated what the RFPs should contain, which created some disagreement within project teams. The consulting group also insisted on top management presence at weekly meetings. While this demonstration of executive commitment was valuable for the first few months, later meetings became too detailed to warrant executive attendance. Finally, too much time was spent educating consultants about the heavy equipment industry. There was some surprise initially at the lack of experience of the consultants sent to work with VCI/Ellison on a day-to-day basis.

Concluding Observations An issue that all companies should address is whether the supply base that supports their industry has global capabilities. Most competitors in the heavy equipment industry operate regionally, which the supply community is structured to support. The issue of a regional versus global industry raises a critical question—is the heavy equipment industry, with its regional perspective and different customer tastes and requirements, a true global industry? How much time should VCI/Ellison spend searching for common interests, including in procurement and design, when perhaps limited opportunities are available?

As VCI/Ellison completes the first major iteration of its global process (three waves of nine projects each that addressed the entire product structure), some managers are openly concerned about losing the discipline associated with this process.

When first introduced the global sourcing process was something new that received special attention from executive leadership and suppliers. Some managers have expressed a concern that internal participants and suppliers already perceive the process is “winding down” and that most of the available savings have been captured.

Maintaining momentum rather than succumbing to complacency will likely require a group that is committed to driving this process forward. In all likelihood that group must be the executive steering committee that is responsible for directing VCI/Ellison’s global efforts.

Discussion Questions

1. What is global sourcing? Are there different levels of global sourcing?

2. What are some of the differences between VCI and Ellison? Can these differences affect the success of the company’s global sourcing projects?

3. Why is this company pursuing integrated global sourcing? Describe the global

process that VCI/Ellison has implemented.

4. The assessment of worldwide suppliers creates an extensive workload. Discuss

how VCI/Ellison supports the analysis requirements faced by each global

sourcing team.

5. Discuss the concept of a “wave.” Why does executive management want each

global sourcing project to last six months and move through a lock-step series of

steps?

6. What was the role of consultants when developing and executing VCI/Ellison’s

global process? What are the advantages and disadvantages of relying on

external support?

7. Discuss the importance of negotiation in VCI/Ellison’s global process. How does

the company ensure that its teams are prepared to negotiate?

8. What are some of the advantages and outcomes that VCI/Ellison has realized

from its global efforts? Exhibit 1 Positive and Negative Features Related to the Business Analyst Position

Positive Features Negative Features Experience from the position builds Managing three projects simultaneously expertise about the global sourcing creates an intense work pace process

Full-time commitment to the process Process has some inefficiencies (faxing, helps the business analyst avoid other handling reams of paper, some job distractions software inefficiencies), creating additional and perhaps unnecessary work burden

Team leader and business analyst are Long and stressful days can affect key “point people” to management and morale and promote turnover suppliers

Given the work required to manage Too many RFI suppliers pass to RFP RFIs, RFPs, and negotiations, the stage, creating intensive work global sourcing process would not requirements for the analyst succeed without the analyst position and a strong analyst

Business analyst position prepares Obtaining drawings for RFPs from individuals for future sourcing careers engineers is a time consuming process