PDF Hosted at the Radboud Repository of the Radboud University Nijmegen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hoofdstuk 2 VOORGESCHIEDENIS

Hoofdstuk 2 VOORGESCHIEDENIS Vanaf hoofdstuk drie komen vele aspecten van het leven in Geleen-Zuid aan bod. Dit hoofdstuk gaat over ”alles wat er al was”. We beginnen met een samenvatting over de zware industrie, die voor de ontwikkeling van heel Geleen van groot belang was en is. Dit stuk is geschreven door Herman de Rooij, voormalig medewerker van DSM-Research. Daarna volgen stukken over bewoning aan de zuidzijde van Geleen voorafgaande aan de realisatie van Plan-Zuid. Met heel lang geleden sporen van Bandkeramiek en van recenter datum o.a. de beschrijving van het oude gehucht Spaans Neerbeek. Dit hoofdstuk wordt afgesloten met een vogelvlucht over de Christus Koningparochie, de jongste parochie van Geleen voordat Geleen- Zuid ontwikkeld werd. VAN STAATSMIJN MAURITS TOT CHEMELOT Voorwoord In 1915 besloot de Nederlandse regering om in Geleen-Lutterade een nieuwe mijn aan te leggen, die de naam Maurits kreeg. Geleen telde toen 3700 inwoners. De voornaamste bron van inkomsten was de landbouw. Een aardig beeld van die tijd, aan de vooravond van de mijnbouw, geeft het boek en de latere TV-serie ”Uit het dagboek van een herdershond”. Honderd jaar later wonen er tien maal zoveel mensen en is Geleen opgegaan in de gemeente Sittard-Geleen. De staatsmijnen heten nu DSM, de mijnbouw is verleden tijd, de fabrieken voor bulkchemie zoals kunstmest (SBB), naftakrakers, polyetheen en de polypropeen-fabrieken zijn verkocht en er is overgebleven een modern inter- nationaal opererende chemische onderneming, die als werkgebieden heeft: hoog- waardige kunststoffen, voeding en farma. De geschiedenis van Geleen is onlosmakelijk verbonden met de komst en groei van de staatsmijnen in Limburg, de latere DSM. -

Bereikbaarheid Zuyderland

versie maart 2021 Zuyderland Medisch Centrum 1 Sittard-Geleen Dr. H. van der Hoffplein 1, 6162 BG Sittard-Geleen T. 088 459 7777 2 Heerlen Henri Dunantstraat 5, 6419 PC Heerlen T. 088 459 7777 3 Kerkrade Wijngracht 45, 6461 AL Kerkrade T. 088 459 7777 Roermond 4 Brunssum Prins Hendriklaan 376, 6443 AE Brunssum T. 088 459 7777 5 Buitenpoli de Egthe De Egthe 1, 6101 EX Echt T. 0475 41 7887 Revalidatie 6 Revalidatie Dr. H. van der Hoffplein 1, 6162 BG Sittard - Geleen T. 088 459 7777 5 19 18 Echt Geestelijke Gezondheidszorg 7 Sittard-Geleen Dr. H. van der Hoffplein 1, 6162 BG Sittard - Geleen T. 088 459 9393 Susteren 8 Heerlen Henri Dunantstraat 5, 6419 PC Heerlen T. 088 459 7777 9 Kerkrade Wijngracht 45, 6461 AL Kerkrade T. 088 459 7777 Born 39 28 10 Brunssum Prins Hendriklaan 376, 6443 AE Brunssum T. 088 459 7777 20 11 Hostel & Inloop Stationsstraat 18-20, 6131 AZ Sittard T. 088 459 4040 35 12 DAC het Karwei Kastelenweg 1-3, 6136 BK Sittard T. 046 451 8914 13 13 Het Arbeidscentrum Millenerweg 8, 6131 KW Sittard T. 046 458 2789 21 15 22 14 16 14 Kinderpsych. dagbeh. Valkstraat 2a, 6135 GC Sittard (Het Drakennest & Het Vossenhol) T. 046 451 8914 12 15 Deeltijdbeh. Ouderen Gelderhof 2, 6136 CC Sittard T. 046 458 3011 Sittard 38 24 16 Kind en Adolecent Geerweg 5, 6135 KB Sittard T. 088 459 0330 32 11 31 17 23 6 zuyderland Geleen 7 1 Zuyderland Zorgcentra 30 27 34 Stein 37 17 Zorgcentra Kantoor Parklaan 10, 6131 KG Sittard T. -

Smart Chemistry Specialisation Strategy

Smart Chemistry Specialisation Strategy “Report on recommendations for the Involvement of Stakeholders and Governance of Regional Innovation Strategies in Limburg” February 2017 1 Table of Contents 1. Description of RIS Governance ...................................................................................... 3 1.1 General Description ................................................................................................. 3 2. Involvement of regional Stakeholders ........................................................................... 7 2.1 OPZuid ...................................................................................................................... 7 2.2 Participation Challenges ........................................................................................ 12 3. Networks and Clusters .................................................................................................. 13 3.1 Brightlands Chemelot Campus Communities ...................................................... 13 3.2 Cluster SourceB: .................................................................................................... 14 4. Identification of the thematic priorities ........................................................................ 15 5. Conclusions and recommendations ............................................................................ 17 5.1 Strengths and weaknesses ................................................................................... 17 5.2 Needs for improvement ........................................................................................ -

Masterplan Chemelot 2030 16 December 2019 - Finale Versie 5

Masterplan Chemelot 2030 16 december 2019 - finale versie 5 Versie/ datum: 16-12-2019 1 Masterplan Chemelot 16/12/2019 Voorwoord Geachte lezer, Voor u ligt het Masterplan Chemelot 2030. Dit Masterplan is de uitwerking op het gebied van ruimte en logistiek van onze “Visie Chemelot 2025”. Centraal in die visie staat onze ambitie om als Chemelot uit te groeien tot de meest veilige, meest duurzame en meest competitieve chemie- en materialen site in Europa in 2025. We staan als maatschappij -en daarmee ook als site- voor grote uitdagingen om een duurzame toekomst voor onze en toekomstige generaties te bouwen. Centraal daarin staat de maatschappelijke ambitie om een circulaire en klimaat neutrale economie te realiseren. Onze doelen zijn helder, maar de weg erheen zullen we samen moeten vormgeven. Dit Masterplan is voor ons één van de belangrijke uitwerkingen voor die duurzame toekomst. Naast duurzaamheid staat ook veiligheid centraal in ons denken en doen. Chemelot heeft mede naar aanleiding van het rapport van de Onderzoeksraad voor Veiligheid en in samenspraak met de overheden ambitieuze veiligheidsdoelen gesteld. Veiligheid is voor ons een absolute prioriteit. Iedere dag weer zijn wij ons bewust van het belang van veiligheid, voor de medewerkers, de bezoekers, maar ook voor de omgeving. Iedereen is vanuit de eigen rol bezig om de veiligheidsprestaties nog verder te verbeteren om onze ambitie waar te maken. Deze veiligheidsambitie heeft een ruimtelijke impact die ook in dit Masterplan is verwerkt. We zijn ervan overtuigd dat de vooruitstrevende Chemelot ambitie en transitie kansen biedt. Deze kansen moeten echter ook financieel onderbouwd worden om de economische kracht van ons cluster én de groei van de werkgelegenheid op en om de site zeker te stellen. -

The Impacts of CO2 Capture Technologies in Power Generation

Copernicus Institute for Sustainable Development and Innovation The impacts of CO 2 capture technologies in power generation and industry on greenhouse gases emissions and air pollutants in the Netherlands Date 8 July 2009 Author(s) Arjan van Horssen (TNO) Takeshi Kuramochi (UU) Magdalena Jozwicka (TNO) Joris Koornneef (UU) Toon van Harmelen (TNO) Andrea Ramírez Ramírez (UU) Project coordinator Erik Lysen (UCE) Keywords Capture CO 2 Greenhouse gas Transboundary air pollution Customer Ministry of VROM Milieu- en Natuur Planbureau Reference number BOLK Number of pages 164 (incl. appendices) Number of appendices 8 BOLK report on CO 2 capture technologies in the Netherlands Preface This study has been performed for the Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency / Planbureau voor de Leefomgeving (contact: Pieter Hammingh) within Dutch programme entitled Policy Research Programme on Air and Climate / Beleidgericht Onderzoeksprogramma Lucht en Klimaat (BOLK) for the Dutch Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and Environment and Environment / Ministerie van Volkshuisvesting, Ruimtelijke Ordening en Milieubeheer (VROM, contact: Jan Wijmenga). The report presents the final results of a second research phase of one out of four projects conducted within the framework. The first phase report ‘The impacts of CO 2 capture technologies on transboundary air pollution in the Netherlands’ by Toon van Harmelen (TNO), Joris Koornneef (UU), Arjan van Horssen (TNO), Andrea Ramírez Ramírez (UU) and René van Gijlswijk (TNO) was published in May 2008. 3 / 164 BOLK report on CO 2 capture technologies in the Netherlands 4 / 164 BOLK report on CO 2 capture technologies in the Netherlands Executive summary Main conclusions − Changes in the level of NEC emissions (National Emission Ceiling Directive, being SO 2, NO x, Particulate Matter, NMVOC and NH 3) are not a bottleneck for CCS implementation. -

The Aftermath of the Closure of the Dutch Coal Mines in South Limburg: Regional Economic and Social Reconstruction

THE AFTERMATH OF THE CLOSURE OF THE DUTCH COAL MINES IN SOUTH LIMBURG: REGIONAL ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL RECONSTRUCTION Hans Kasper, Maastricht University and Etil BV This case study focuses on 35 years of economic redevelopment, reconversion or restructuring after the closure of the Dutch coal mines in the South Limburg mining district. It explicates what strategic decisions and measures were taken to solve the economic and social problems that occurred in this Dutch area after the closure of the coal mines, a process that was announced on December 17, 1965, by the Dutch government. Based on real-life experiences, this case study discusses the role and relevance of strategic planning, project management, human resource management, labor market policy, social policy, public policy and regional policy in restructuring the economic structure of an area in which a dominant player ended its activities in a rather short period. The case tackles not only the economic impact but also the social impact of the coal mine closures. The case is intended to be used as the basis for class discussion rather than to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of a management situation. Copyright © 2012, ECCH No part of this publication may be copied, stored, transmitted, reproduced or distributed in any form or medium whatsoever without the written permission of the copyright owner. Case study on the aftermath of the closure of the Dutch coal mines in South Limburg 1 1. The coal industry in the Netherlands 1.1 General overview The production of coal originally began in the Netherlands in the 12th century on a very small scale. -

Maastricht-Aachen Airport

Arial photo (2003) Maastricht-Aachen Airport 1:20.000 MAASTRICHT-AACHEN AIRPORT 42 MST - MAASTRICHT-AACHEN AIRPORT AIRPORT-ORGANIZATION Name / Address Maastricht Aachen Airport, Vliegveldweg 90, NL-6199 AD Maastricht, Netherlands Website www.maa.nl IATA / ICAO code MST / EHBK Position (LAT/LONG) 50°54´57”N / 005°46´37”E Opening hours 06:00-23:00 hrs (Noise) restrictions Night curfew 23:00-06:00 hrs Ownership NV Luchthaven Maastricht Operator NV Luchthaven Maastricht (civil) users Nederlandse Luchtvaartschool (NLS), European air traffic control center Eurocontrol + General aviation License Article 33 Air traffic law, 28-04-2000* Shareholders** - NV Industriebank LIOF -Provincie Limburg - KVK Limburg-Zuid -Gemeente Maastricht - KvK Aachen (D) -Gemeente Tongeren(B) Comments: *New definite license airfield is planned at the end of 2004. **In 2004 is Holding Businesspark Luchthaven Maastricht (Maastricht Aachen Airport BV and Businesspark MAA BV) sold to a private partner. FINANCE (x €1.000,-, 2003): Company results: 10.677 Company costs: 12.717 -Airport charges 4.028 -Salaries & social costs 8.704 -Rentals & concessions 1.142 -Others (e.g. car parking) 553 Investments: 6.046 REGION Regional profile EURegion Nearest city: Maastricht -Population (x 1.000): 122,2 -Potential market area 1hr by car 2hrs by car 1hr by train 2hrs by train weighted with distance decay (2004, x 1 million pax): 7,3 36,0 3,1 23,5 10,9 Business (airport linked): TechnoPortEurope, Bamford Employment (2003)*: *(Source: Maastricht Aachen Airport, 2004) -Employed direct 171 -

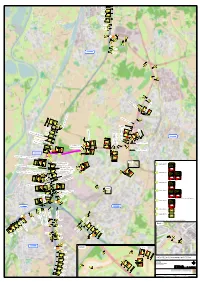

Definitief - Projectplan Waterwet

Definitief - Projectplan Waterwet Herinrichting Geleenbeek deelgebied 20 fase 1 te Sittard-Geleen 1 december 2019 1 Inhoudsopgave Deel 1 Herinrichting Geleenbeek........................................................................................ 4 1.1 Voorgeschiedenis ................................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Beschrijving plangebied ...................................................................................................... 4 1.3 Projectdoelen ........................................................................................................................ 7 1.4 Beschrijving van de waterstaatswerken (gewenste situatie) ......................................... 8 1.5 Beschikbaarheid gronden ................................................................................................... 9 1.6 Effecten van het plan ........................................................................................................... 9 1.7 Wijze waarop het werk zal worden uitgevoerd .............................................................. 10 1.8 Beschrijving van de te treffen voorzieningen ................................................................. 10 1.8.1 Beperken nadelige gevolgen van het plan ............................................................. 10 1.8.2 Beperken nadelige gevolgen van de uitvoering..................................................... 10 1.8.3 Financieel nadeel ...................................................................................................... -

Commission Supports Industrial Restructuring in Zuid-Limburg (NL)

IP/97/275 Brussels, 9 April 1997 Commission Supports Industrial Restructuring in Zuid-Limburg (NL) The Dutch region of Zuid-Limburg is to receive ECU 65.52 million from the EU’s Structural Funds to cope with industrial and structural change. The aid comes under a programme approved by the European Commission today in principle and aims at improving the employment prospects for the working population, increasing the competitiveness of SME’s and protecting the environment of the region. The programme will contribute to the creation of 4000 new jobs, 1577 temporary jobs and will provide training for 4970 employees and 2270 unemployed. In addition, seven new technology or training centres will be set up and more than 170 ha of business sites created or renovated. The programme approved in principle today completes the series of EU-programmes for Dutch regions in industrial decline (obj. 2) and brings the total EU-funding for these regions up to about ECU 361.97 million. Regional socio-economic situation The Objective 2 region Zuid-Limburg still bears the traces of its mining past. Its labour market encompasses parts of the Heerlen and Sittard districts and more specifically the municipalities of Beek, Born, Brunssum, Geleen, Heerlen, Kerkrade, Landgraaf, Nuth, Schinnen, Sittard and Stein. About 15% of the working population is officially unemployed. The hidden unemployment is also very high, and total unemployment is probably in the region of 20%. On average, unemployment among women is 4 percentage points higher than among men. The economy is highly dependent on industry, thus making it vulnerable to business cycles. -

Decarbonisation Options for Large Volume Organic Chemicals Production, Sabic Geleen

DECARBONISATION OPTIONS FOR LARGE VOLUME ORGANIC CHEMICALS PRODUCTION, SABIC GELEEN Carina Oliveira, Ton Van Dril 04 May 2021 Manufacturing Industry Decarbonisation Data Exchange Network Decarbonisation options for Large Volume Organic Chemicals production, SABIC Geleen © PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency; © TNO The Hague, 2021 PBL publication number: 3718 TNO project no. 060.33956 / TNO 2021 P10361 Authors Oliveira, C. and van Dril, A.W.N Acknowledgements We would like to thank Bert Bosman (SABIC), Bart Eurlings (SABIC), Herbert Zondag (TNO), Marija Saric (TNO), Octavian Partenie (TNO), Rajat Bhardwaj (TNO) and Kira West (TNO) for their help and valuable input. MIDDEN project coordination and responsibility The MIDDEN project (Manufacturing Industry Decarbonisation Data Exchange Network) was initiated and is also coordinated and funded by PBL and ECN part of TNO (which is named TNO EnergieTransitie after 1-1-2020). The project aims to support industry, policymakers, analysts, and the energy sector in their common efforts to achieve deep decarbonisation. Correspondence regarding the project may be addressed to: D. van Dam (PBL), [email protected] or S. Gamboa Palacios (TNO), [email protected] This publication is a joint publication by PBL and TNO EnergieTransitie and can be downloaded from: www.pbl.nl/en. Parts of this publication may be reproduced, providing the source is stated, in the form: Oliveira, C. & van Dril, A.W.N. (2021), Decarbonisation options for large volume organic chemicals production, SABIC Geleen. PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency and TNO EnergieTransitie, The Hague. PBL Netherlands Environmental Assessment Agency is the national institute for strategic policy analysis in the fields of the environment, nature and spatial planning. -

Detail 2 Detail 1

omleiding hmp 229.8 hmp hmp 230.0 hmp dicht (N294) Urmonderbaan N294 hmp 230.4 hmp 13 volg Zuyderland 8 Geleen hmp 230.9 hmp 13 volg Zuyderland 8 Geleen hmp 231.2 hmp 13 hmp 231.8 hmp 13 13 47 Born 12 12 13 13 13 13 hmp 233.1 Born 13 hmp 233.3 13 12 13 12 13 12 13 afkruisen "Maastricht" op ANWB-mast op "Maastricht" afkruisen 12 12 A2 Maastricht A2 volg afkruisen "Maastricht" op ANWB-bord omleiding Toerit 48 Maastricht afkruisen "Maastricht","Geleen" op ANWB-mast op "Maastricht","Geleen" afkruisen dicht omleiding dicht baan (N294) baan Urmonder- volg 12 Maastricht Geleen Zuyderland 8 afkruisen "Maastricht" op ANWB-mast op "Maastricht" afkruisen 13 13 13 omleiding hmp 236.5 hmp afkruisen "Maastricht" op ANWB-bord op "Maastricht" afkruisen omleiding hmp 236.7 hmp dicht dicht A2 Maastricht Toerit 48 Toerit 14 Urmonderbaan hmp 237.0 hmp N294 volg 13 A2 14 omleiding volg op ANWB-portaal op op ANWB-bord - hmp 237.2 hmp - ANWB-bord op afkruisen "Maastricht" afkruisen Maastricht A2 afkruisen "Transferum","Chemelot","Zuid-Limburg" afkruisen dicht Zuyderland 8 Sittard Maastricht Toerit 48 Toerit 14 Geleen hmp 237.2 hmp 13 volg 13 A2 Maastricht Omleiding 14 volg afkruisen "Maastricht" op ANWB-mast afkruisen "Maastricht" op ANWB-bord 13 - hmp 237.5 hmp - afkruisen "Maastricht" op ANWB-bord op "Maastricht" afkruisen Zuyderland 8 afkruisen "Geleen" op ANWB-bord op "Geleen" afkruisen Geleen 14 dicht 14 hmp 237.8 hmp A2 Maastricht 13 A2 afkruisen "Maastricht" op ANWB-mast Toerit 48 Toerit - hmp 238.1 hmp - afkruisen "Geleen" op ANWB-bord op "Geleen" afkruisen -

Historie Nederlandse Steenkolenwinning

12-2014 Lesbrief 2 Historie Nederlandse steenkolenwinning. Bij bodemvondsten in de omgeving van Romeinse villa’s in Zuid-Limburg zijn brokstukken steenkool gevonden. De Romeinen gebruikten klaarblijkelijk al steenkool om hun villa’s te verwarmen. De gevonden steenkool komt in ieder geval overeen met de magere kool die in het Wormdal aan de oppervlakte komt. Daarom ligt het voor de hand dat de Romeinen hun steenkool ook hier vandaan hebben gehaald. In tijden dat hout heel gemakkelijk te krijgen was, raakte steenkool uit de gratie. Alleen als steenkool dicht aan de oppervlakte lag en daardoor gemakkelijk te delven was, was het een goedkopere brandstof dan hout. Toen in middeleeuws Europa de houtvoorraad slonk werd het economisch interessanter om steenkool te gaan winnen. Begin met kolenwinning in Zuid-Limburg Steenkool werd al zeer lang gevonden in Zuid-Limburg. De eerste steenkool werd gewonnen in de buurt van de abdij van Rolduc in Kerkrade. Uit de geschiedenis van Rolduc, die is vastgelegd in de Annales Rodenses, blijkt dat vermoedelijk al rond de 11 de eeuw steenkool in dagbouw werd gewonnen in het dal van het riviertje de Worm, een zijrivier van de Roer. De Annales Rodenses zijn dagboeken van de abdij Kloosterrade (Rolduc), die gesticht werd in 1104. Steenkool in de wanden van het riviertje de Worm Kaart van concessies verleend in de 19de eeuw. In het begin van de 14de eeuw raakten de steenkolenlagen die aan de oppervlakte kwamen min of meer uitgeput, en moest men ondergronds verder. Dit gebeurde in zogenaamde stollenbouw, waarbij in de wand van een heuvel of een rivierdal horizontale mijngangen werden aangelegd.