J E F F Ly N N E

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Ai 13 U Ivis

AI_13 U IVIS Rabbit," and Alison Mosshart THE JOY JESSIE J glistens on Lennon & McCartney's FORMIDABLE Who You Are "Tomorrow Never Knows," while The Big Roar Producers: various Björk's "Army of Me" is sub- Producers: The Joy Lava/Universal Republic jected to an aggressive remix Formidable, Neak Menter, Release Date: April 12 that blends perfectly with the Rich Costey The latest product of London's star - new tracks. The soundtrack's Canvasback/Atlantic making BRIT School arrives in America most tender moment begins Release Date: March 15 with no shortage of at -home hype: Even before the U.K. with a male voice, Yoav, who Anyone who saw the Joy For - release of her debut album, "Who You Are," Jessie J won trades verses packed with vul- midable's blistering set at Bill- the BBC's Sound of 2011 poll and the Critics' Choice BRIT nerability with Browning on the board's South by Southwest Award, and when it came out last month in the United Pixies' "Where Is My Mind ?" showcase in late March knows Kingdom, the set debuted at No. 2 -right behind fellow Amid a rush of male- targeted that this Welsh trio doesn't do BRIT brat Adele's "21." Like that "Chasing Pavements" female power, it's the rare mo- anything small. Even the band's singer, Jessie J owns a big voice rich with old -soul intensity. ment that asks the audience to 2009 indie debut mini -LP, "A Here, she uses it most powerfully in "Mamma Knows Best," pause for reflection. -

English Song Booklet

English Song Booklet SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER SONG NUMBER SONG TITLE SINGER 100002 1 & 1 BEYONCE 100003 10 SECONDS JAZMINE SULLIVAN 100007 18 INCHES LAUREN ALAINA 100008 19 AND CRAZY BOMSHEL 100012 2 IN THE MORNING 100013 2 REASONS TREY SONGZ,TI 100014 2 UNLIMITED NO LIMIT 100015 2012 IT AIN'T THE END JAY SEAN,NICKI MINAJ 100017 2012PRADA ENGLISH DJ 100018 21 GUNS GREEN DAY 100019 21 QUESTIONS 5 CENT 100021 21ST CENTURY BREAKDOWN GREEN DAY 100022 21ST CENTURY GIRL WILLOW SMITH 100023 22 (ORIGINAL) TAYLOR SWIFT 100027 25 MINUTES 100028 2PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 100030 3 WAY LADY GAGA 100031 365 DAYS ZZ WARD 100033 3AM MATCHBOX 2 100035 4 MINUTES MADONNA,JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE 100034 4 MINUTES(LIVE) MADONNA 100036 4 MY TOWN LIL WAYNE,DRAKE 100037 40 DAYS BLESSTHEFALL 100038 455 ROCKET KATHY MATTEA 100039 4EVER THE VERONICAS 100040 4H55 (REMIX) LYNDA TRANG DAI 100043 4TH OF JULY KELIS 100042 4TH OF JULY BRIAN MCKNIGHT 100041 4TH OF JULY FIREWORKS KELIS 100044 5 O'CLOCK T PAIN 100046 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100045 50 WAYS TO SAY GOODBYE TRAIN 100047 6 FOOT 7 FOOT LIL WAYNE 100048 7 DAYS CRAIG DAVID 100049 7 THINGS MILEY CYRUS 100050 9 PIECE RICK ROSS,LIL WAYNE 100051 93 MILLION MILES JASON MRAZ 100052 A BABY CHANGES EVERYTHING FAITH HILL 100053 A BEAUTIFUL LIE 3 SECONDS TO MARS 100054 A DIFFERENT CORNER GEORGE MICHAEL 100055 A DIFFERENT SIDE OF ME ALLSTAR WEEKEND 100056 A FACE LIKE THAT PET SHOP BOYS 100057 A HOLLY JOLLY CHRISTMAS LADY ANTEBELLUM 500164 A KIND OF HUSH HERMAN'S HERMITS 500165 A KISS IS A TERRIBLE THING (TO WASTE) MEAT LOAF 500166 A KISS TO BUILD A DREAM ON LOUIS ARMSTRONG 100058 A KISS WITH A FIST FLORENCE 100059 A LIGHT THAT NEVER COMES LINKIN PARK 500167 A LITTLE BIT LONGER JONAS BROTHERS 500168 A LITTLE BIT ME, A LITTLE BIT YOU THE MONKEES 500170 A LITTLE BIT MORE DR. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home -

Task Force Recommends GT Savannah Cuts

Friday, April 8, 2011 • Volume 96, Issue 28 • nique.net Global goods Students experienced different cultures at AIESEC’s Global Village.415 TechniqueThe South’s Liveliest College Newspaper Task force recommends GT Savannah cuts By Vijai Narayanan placing them with co-op and intern- shared communications with students, News Editor ship opportunities that are in line with faculty and staff of the Savannah cam- the needs of local industry and gov- pus reassuring them of the Institute’s The future of Tech’s Savannah cam- ernment. Another suggested proposal commitment to the Savannah and pus will be determined in the coming is to add professional master’s degree coastal Georgia area, but informing months as the Institute reviews the programs, professional and executive them that the mission of the campus mission of its satellite campus in rela- certificate programs and research ac- is under review,” said Institute spokes- tion to other long-term initiatives and tivities. The task force is also explor- person Matt Nagel. goals. A task force created by the Pro- ing the potential of expanding applied According to Nagel, these recom- vost’s Office in Dec. 2010 issued a se- research activities to drive economic mendations will be finalized in the ries of preliminary recommendations development in the region. coming weeks. Once approved by this past week regarding the future of According to a statement released Institute President G.P. “Bud” Peter- the Savannah campus. by the Institute, the realignment is son, they must also be approved by the Photo courtesy of Communications & Marketing Among the options being consid- meant to ensure that the Savannah Board of Regents before being imple- ered are phasing out undergraduate program is financially viable. -

Britney Spears Nya Singel: ”Till the World Ends”

2011-03-07 11:30 CET Britney Spears nya singel: ”Till The World Ends” Singeln nummer två från Britney Spears nya album ”Femme Fatale” är nu släppt. ”Till The World Ends” heter den nya singeln som är skriven och producerad av Dr. Luke och Max Martin. ”Till The World Ends” följer upp miljonsäljande ”Hold It Against Me” och dessa två singlar leder nu väg till albumreleasen av Britney Spears sjunde album ”Femme Fatale” den 25 mars. Britney Spears om nya albumet: ”I think Femme Fatale speaks for itself… I wanted to make a fierce dance record where each song makes you want to get up and move…” I fredags gästade Britney Spears Ryan Seacrests radioshow för en liveintervju. Lyssna på när Britney pratar om samarbetet med will.i.am, Max Martin, nya singeln ”Till The World Ends” - och Britney svarar också på frågan om det blir någon turné framöver. Lyssna på hela intervjun här. “Femme Fatale” tracking list: 1. Till The World Ends (Produced by Dr. Luke, Max Martin and Billboard) 2. Hold It Against Me (Produced by Dr. Luke, Max Martin and Co-produced by Billboard) 3. Inside Out (Produced by Dr. Luke, Max Martin and Billboard) 4. I Wanna Go (Produced by Max Martin and Shellback) 5. How I Roll (Produced by Bloodshy, Henrik Jonback and Magnus) 6. (Drop Dead) Beautiful featuring Sabi (Produced by Benny Blanco, Ammo, JMIKE and Billboard) 7. Seal It With A Kiss (Produced by Dr. Luke, Max Martin and Dream Machine) 8. Big Fat Bass featuring will.i.am (Produced by will.i.am) 9. -

Til the World Ends Pdf Free Download

TIL THE WORLD ENDS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Julie Kagawa,Ann Aguirre,Karen Duvall | 361 pages | 29 Jan 2013 | Luna Books | 9780373803491 | English | Don Mills, Ont., Canada Til the World Ends PDF Book Retrieved January 30, Archived from the original on March 14, As the second verse begins, she dances provocatively with her male dancers. Swiss Hitparade. Retrieved April 7, Slant Magazine. Pieces of April When I hear that, I fucking blow the speakers out and I order everybody to dance. Retrieved May 18, Retrieved May 22, Retrieved March 14, Then they added the Nicki Minaj verse. Entertainment Weekly. She also joined Spears to perform the verse in select cities. It stayed for seventeen weeks on the chart. Sweden Sverigetopplistan [38]. Retrieved September 24, As the second verse begins, she dances provocatively with her male dancers. Boston Herald. The melody's cross-rhythm continues into a chant-like segment, in which "whoa-oh-oh-oh" is repeated. The New York Times Company. Israeli Airplay Chart. Retrieved July 17, Artist: Three Dog Night. An accompanying music video for the "Till the World Ends" was released on April 6, Like, when I hear my own songs on the radio I have to kind of turn it down or change the radio or whatever. US Billboard Hot [63]. Retrieved May 4, Plus, sweaty dancers in tunnels pulsing and writhing in sync to the music? Yes No. December 13, Irish Singles Chart. Recorded Music NZ. Archived from the original on May 10, Select "Tutti gli anni" in the "Anno" drop-down menu. Luke production, but "somehow it's Brit that manages to come out on top. -

Britney Spears Live: the Femme Fatale Tour Mp3, Flac, Wma

Britney Spears Live: The Femme Fatale Tour mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic / Pop Album: Live: The Femme Fatale Tour Country: Australia Released: 2011 Style: Synth-pop MP3 version RAR size: 1328 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1328 mb WMA version RAR size: 1873 mb Rating: 4.9 Votes: 499 Other Formats: AUD DMF MP2 APE FLAC WMA MMF Tracklist 1 Femme Fatale Video 2 Hold It Against Me 3 Up N' Down 4 3 5 Piece Of Me 6 Sweet Seduction Video 7 Big Fat Bass 8 How I Roll 9 Lace And Leather 10 If U Seek Amy 11 Temptress Video 12 Gimme More 13 (Drop Dead) Beautiful 14 Don't Let Me Be The Last To Know 15 Boys 16 Code Name: Trouble Video 17 ...Baby One More Time 18 S&M 19 Trouble For Me 20 I'm A Slave 4 U 21 I Wanna Go 22 Womanizer 23 Sexy Assassin Video 24 Toxic 25 Till The World Ends Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Shiloh Standing, Inc. Copyright (c) – Shiloh Standing, Inc. Licensed To – RCA Records Distributed By – Sony Music Entertainment Australia Pty Ltd. Pressed By – Sony DADC Australia – A0100968687XA511 Credits Art Direction, Design – Jackie Murphy Design [Logo] – Jeri Heiden, Nick Steinhard* Directed By [Co-Musical Director] – Marc Delcore Directed By [Femme Fatale Tour] – Jamie King Directed By [Musical Director] – Simon Ellis Director Of Photography – Reed Smoot Executive-Producer – Adam Leber, Britney Spears, Gari Ann Douglass, Larry Rudolph, Steve Schklair Film Director, Film Producer – Ted Kenney Film Editor – Don Wilson , George Bellias Management – Adam Leber, Larry Rudolph Photography By [Cover] – Randee St. -

To Search This List, Hit CTRL+F to "Find" Any Song Or Artist Song Artist

To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Song Artist Length Peaches & Cream 112 3:13 U Already Know 112 3:18 All Mixed Up 311 3:00 Amber 311 3:27 Come Original 311 3:43 Love Song 311 3:29 Work 1,2,3 3:39 Dinosaurs 16bit 5:00 No Lie Featuring Drake 2 Chainz 3:58 2 Live Blues 2 Live Crew 5:15 Bad A.. B...h 2 Live Crew 4:04 Break It on Down 2 Live Crew 4:00 C'mon Babe 2 Live Crew 4:44 Coolin' 2 Live Crew 5:03 D.K. Almighty 2 Live Crew 4:53 Dirty Nursery Rhymes 2 Live Crew 3:08 Fraternity Record 2 Live Crew 4:47 Get Loose Now 2 Live Crew 4:36 Hoochie Mama 2 Live Crew 3:01 If You Believe in Having Sex 2 Live Crew 3:52 Me So Horny 2 Live Crew 4:36 Mega Mixx III 2 Live Crew 5:45 My Seven Bizzos 2 Live Crew 4:19 Put Her in the Buck 2 Live Crew 3:57 Reggae Joint 2 Live Crew 4:14 The F--k Shop 2 Live Crew 3:25 Tootsie Roll 2 Live Crew 4:16 Get Ready For This 2 Unlimited 3:43 Smooth Criminal 2CELLOS (Sulic & Hauser) 4:06 Baby Don't Cry 2Pac 4:22 California Love 2Pac 4:01 Changes 2Pac 4:29 Dear Mama 2Pac 4:40 I Ain't Mad At Cha 2Pac 4:54 Life Goes On 2Pac 5:03 Thug Passion 2Pac 5:08 Troublesome '96 2Pac 4:37 Until The End Of Time 2Pac 4:27 To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Ghetto Gospel 2Pac Feat. -

Catalogue Karaoké Mis À Jour Le: 29/07/2021 Chantez En Ligne Sur Catalogue Entier

Catalogue Karaoké Mis à jour le: 29/07/2021 Chantez en ligne sur www.karafun.fr Catalogue entier TOP 50 J'irai où tu iras - Céline Dion Femme Like U - K. Maro La java de Broadway - Michel Sardou Sous le vent - Garou Je te donne - Jean-Jacques Goldman Avant toi - Slimane Les lacs du Connemara - Michel Sardou Les Champs-Élysées - Joe Dassin La grenade - Clara Luciani Les démons de minuit - Images L'aventurier - Indochine Il jouait du piano debout - France Gall Shallow - A Star is Born Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen La bohème - Charles Aznavour A nos souvenirs - Trois Cafés Gourmands Mistral gagnant - Renaud L'envie - Johnny Hallyday Confessions nocturnes - Diam's EXPLICIT Beau-papa - Vianney La boulette (génération nan nan) - Diam's EXPLICIT On va s'aimer - Gilbert Montagné Place des grands hommes - Patrick Bruel Alexandrie Alexandra - Claude François Libérée, délivrée - Frozen Je l'aime à mourir - Francis Cabrel La corrida - Francis Cabrel Pour que tu m'aimes encore - Céline Dion Les sunlights des tropiques - Gilbert Montagné Le reste - Clara Luciani Je te promets - Johnny Hallyday Sensualité - Axelle Red Anissa - Wejdene Manhattan-Kaboul - Renaud Hakuna Matata (Version française) - The Lion King Les yeux de la mama - Kendji Girac La tribu de Dana - Manau (1994 film) Partenaire Particulier - Partenaire Particulier Allumer le feu - Johnny Hallyday Ce rêve bleu - Aladdin (1992 film) Wannabe - Spice Girls Ma philosophie - Amel Bent L'envie d'aimer - Les Dix Commandements Barbie Girl - Aqua Vivo per lei - Andrea Bocelli Tu m'oublieras - Larusso -

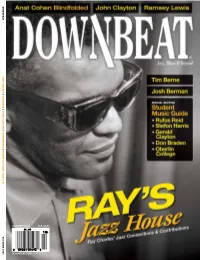

Downbeat.Com October 2010 U.K. £3.50

U.K. £3.50 U.K. ctober 2010 2010 ctober downbeat.com o DownBeat Ray ChaRles // tim BeRne // John Clayton // Josh BeRman // wheRe To StuDy Jazz 2011 oCtoBer 2010 OCTOBER 2010 Volume 77 – Number 10 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Ed Enright Associate Editor Aaron Cohen Art Director Ara Tirado Production Associate Andy Williams Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Kelly Grosser AdVertisiNg Sales Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sue Mahal 630-941-2030 [email protected] offices 102 N. Haven Road Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] customer serVice 877-904-5299 [email protected] coNtributors Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, John McDonough, Howard Mandel Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Michael Point; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, How- ard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Robert Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Jennifer Odell, Dan -

Round Section (Warmup, Punches, Kicks, Turbo, Finesse

Section (Warmup, Side (Right-A, Right-B, Left-A, Round Punches, Kicks, Artist Title Left-B, Right and Left-B) Turbo, Finesse, etc.) 1 Fatboy Slim The Rockafella Skank 1 Armand Van Helden Funk Phenomena 1 The Fugees Ready Or Not 1 DJ Party Delicious 1 INOJ Time After Time To Kool Chris (feat. 1 Ralphi Rosario and D. Gotta Get Up Blakely) 1 Madonna Nothing Really Matters 1 To Kool Chris Keep On Pushin' 1 Klubbheads Kickin' Hard 1 Turbo n/a Fatboy Slim The Rockafella Skank 2 Finesse Both Ricky Martin La Copa de la Vida 2 Yaz Don't Go 2 The Vengaboys Up and Down KC and the Sunshine 2 Get Down Tonight Band 2 To Kool Chris Big Ole Booty Somethin' For the 2 My Love Is the Shhh! People 2 2 Unlimited No Limit 2 Warmup Sesame Street Sesame Street Theme 2 B Rock My Baby Daddy 2 Cooldown Both Enigma The Child In Us 2 Tito Nieves I Like It Like That 2 Brooklyn Bounce Get Ready to Bounce KC and the Sunshine 2 Get Down Tonight Band 2 The Offspring Pretty Fly (For a White Guy) 2 Mousse T. Horny 2 Bang Gang I Like to Move It 3 Cooldown Both Madonna Shanti/Ashtangi 3 Salt-N-Pepa Push It 3 Destiny's Child Bills, Bills, Bills 3 The Vengaboys We Like to Party 3 69 Boyz Beep-Beep 3 Warmup Will Smith Miami C'mon and Ride It (The 3 Warmup Quad City DJ's Train) JT Money and the 3 Shake Whatcha Mama Gave Ya Poison Clan 3 Mighty Dub Katz Magic Carpet Ride 3 Warmup Both Herbie Right Type of Mood The Tamperer (feat.