Women's Employment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parivartan Sangh Also Actively Contributes Towards the “Kanyadaan” in Every Way Possible, Be It in Form of Financial Aid Or Any Other Assistance Required

Established by Bhai Rakesh since 2005 Free Ambulance Services Free Bus Services Free Eye Care Camp Blood Donation Camp Free Medical Services Free Children and Women Education Financial Help for Poor Girls in Marriages Equipments given to Physically Handicapped people Donation for Religious Activities Since 2007, we have undertaken many activities for health care in Gurgaon , Haryana. Our ambulance service can be availed by anyone in need 24X7 by calling on 9717060202. Number of times our ambulance service are served : In 2008 : 134 times In 2010 : 987 times In 2011 : 1683 times In 2012 : 3744 times In 2013 : 5000 times Girls in rural areas are forced to quit studies due to various reasons, the most prominent of them is transportation and the travel time taken in reaching School/Colleges. Since Higher Education couldn't be brought to their door steps, the other option was to provide the girls with a mode of transport which is safe and preferably free. We are providing free transportation facilities to the female students so that they can commute without having any worry about their safety and well being. Different Route Services : Route No. 1 (120 Girls ) : Badhsahpur, Farrukhnagar, Gurgaon, Wazirpur mor, Maarakpur, khera Jhanjhrola, Jurola, Patli, Dhanawas, Khentawas, Jhundsarai, Hayatpur. Route No. 2 (170 Girls) : Gairatpur Bass, Tikli, Aklimpur, Badhshahpur, Fazilpur, Tikri, Islampur, Begampur Khatola. Route No. 3 (140 Girls) : Sikohpur ,Hasanpur, Darbaripur, Palra, Noorpur, Kherki Daula. We have organized 430 eye care camp. 18873 people free cataract (Motiabind) operation. 77 people eye operation of pupil. Eye operation of 27 blind people who lost their eyes through mishappening. -

Raheja Ayana Residences

https://www.propertywala.com/raheja-ayana-residences-gurgaon Raheja Ayana Residences - Sector-79, Gurgaon 3 & 4 BHK apartments available at Raheja Ayana Residences Raheja Developers present Raheja Ayana Residences with 3 & 4 BHK apartments available at Sector-79 Gurgaon. Project ID : J811900431 Builder: Raheja Developers Properties: Apartments / Flats Location: Raheja Ayana Residences, Sector-79, Gurgaon - 122002 (Haryana) Completion Date: Jan, 2016 Status: Started Description Raheja Ayana Residences is one of the super luxury apartments developed by Raheja Developers. The residential development is located in Sector 79 B, Gurgaon. The project offers 3BHK and 4BHK flats at very competitive and affordable price. It is well planned and is built with all modern amenities. Total Area: 5.1 acres Number of Floors: G + 3 Amenities Garden Play Area 24Hr Backup Maintenance Staff Security One of the fastest growing real estate developers in India, Raheja Developers was incorporated in 1990 by Mr. Navin M Raheja. Driven by the values of integrity and ethics, the builders aim at providing luxury residential places within an affordable price. In the span of nearly 25 years, the builders have traversed a path of a steady growth and rapid expansion not only across NCR but also pan-India with winning several awards. Features Luxury Features Security Features Power Back-up Centrally Air Conditioned Lifts Security Guards Electronic Security RO System High Speed Internet Wi-Fi Intercom Facility Fire Alarm Lot Features Lot Private Terrace Balcony Private -

Badshahpur Assembly Haryana Factbook

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/HR-76-0118 ISBN : 978-93-5293-474-4 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 157 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency at a Glance | Features of Assembly as per 1-2 Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps 2 Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency in District | Boundaries 3-8 of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary Constituency | Town & Village-wise Winner Parties- 2014-PE, 2014-AE and 2009-PE Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 9-14 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Towns and Villages by 15-17 Population Size | Sex Ratio (Total -

International Journal of Legal & Social Studies ISSN 2394

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF LEGAL AND SOCIAL STUDIES VOL I ISSUE II ISSN 2394 -1936 PUBLISHING PARTNER For latest Issue - Click here. International Journal of Legal & Social Studies ISSN 2394 – 1936 Vol. 1 October 2019 Issue II A CRITICAL COUNTERPOINT POSITION OF NEW DELHI ANCIENT LOCAL HOTEL AREA AND WORLD MARK, VULNERABILITIES AND SUSTAINABLE DEVELOPMENT IN THE BOUNDARIES OF MAHIPALPUR VILLAGE – A CONTRASTIVE SOCIOECONOMICAL ANALYSIS CONCERNING EDUCATIONAL PERSPECTIVE BASED ON SOCIAL CAPITAL AND HUMAN RIGHTS ADMINISTRATION OF CRIMINAL JUSTICE IN INDIA- AN ANALYSIS THE MUDDLED NOTIONS ON WRONGFUL DEATH AND ABORTION --A CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS INDECENT REPRESENTATION OF WOMEN- A PERSPECTIVE TRIPLE TALAQ: WHERE IS A WOMAN’S RIGHT TO EQUALITY? RELEVANCE OF INTERNATIONAL HUMANITARIAN LAW VIS-À-VIS SYRIAN CIVIL WAR ____________________________________________ ISSN 2394-1936 EDITORIAL BOARD EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Dr.Kavita Singh Associate Professor (Law), The W.B. National University of Juridical Sciences , Kolkata ASSOCIATE EDITORS Mr. Niteesh Kumar Upadhyay, (Assistant Professor, Galgotias University, Delhi) Dr. Prachi V. Motiyani , (Assistant Professor, University School of Law, Gujarat University, Ahmedabad) Ms. Anita Yadav, (Assistant Professor, D.U. Delhi University ) Ms. MrinaliniBanerjee ( Assistant Professor, GD GoenkaUniversiy, Delhi) ASSISTANT EDITORS Mr. Jagmohan Bajaj, (Special Envoy in Ministry of Education Science and Technology, Republic of Kosovo) Dr. Ali Khaled Ali Qtaishat (Assistant Professor, Attorney & Legal Consultant, District Manger of World Mediation Center, Middle East) Dr. EnasQutieshat, Faculty of Law, Philadelphia University (Amman, Jordan) Dr. MetodiHadji-Janev, Associate Professor, International Law, University GoceDelcev, Macedonia Ms. Maryam Kalhor, (LL.M. Andhra University) Consultant and Legal Practitioner, Republic of Iran Mr. Ashish Kumar Sinha (Assistant Professor of Law BIL, India) Mr. -

Report Integrated Water Resources Management of Sohna Division, Gurgaon District, Haryana

Report Integrated Water Resources Management of Sohna Division, Gurgaon District, Haryana TERI School of Advanced Studies, Plot No. 10 Institutional Area, Vasant Kunj, New Delhi - 110 070, India www.terisas.ac.in Tel. +91 11 71800222 (25 lines), Fax +91 11 26122874 Foreword Mr. Amit Khatri, IAS DC, District Administration Gurugram Gurugram, the millennium city has been struggling with water crisis. The geographical area of Gurugram district as per 2011 Census is 1258.00 square kilometers. With more than 77% of it’s area as rural and under agriculture, yet no perennial river, the district is increasingly relying on the canal water from Western Yamuna Canal system for domestic use and groundwater for agricultural and commercial use. Only about 10 percent of the agricultural area in the district is rainfed, a mighty 98.7% of the irrigated agriculture is through borewells dismally resulting in 100% of the area under the Gurugram district falling in the over-exploited zone. There have been initiatives undertaken by various departments of the Administration be it in terms of Pond rejuvenation, rainwater harvesting structures, plantation etc. However, because of lack of adequate R&D and a holistic strategy it inevitably thus which led to failures inevitably, thus it raised the need for learning from past experiences and to understand the gravity of the situation with on-ground feedback and urgency with specifications owing to the Gurugram land and situation. Thus, GuruJal was conceived an initiative with the objective of addressing the issues of water scarcity, ground-water depletion, flooding and stagnation of water in Gurugram. -

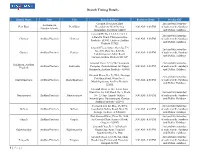

Branch Timing Details

Branch Timing Details Branch Name State City Branch Address Business Hours Weekly Off Ground Floor And First 2nd and 4th Saturday Andaman & Port Blair Port Blair Floor,Survey No 104/1/2, 9:30 AM - 3:30 PM of each month, Sundays Nicobar Islands Junglighat, Port Blair 744103 and Public Holidays Ground Flr No 8-8-1,8-8-2 & 8-8- 2nd and 4th Saturday 3,Gandhi Road, Chittoorandhra Chittoor Andhra Pradesh Chittoor 9:30 AM - 4:30 PM of each month, Sundays Pradesh - 517001 Chittoor Andhra and Public Holidays Pradesh 517325 Ground Floor, Satya Akarsha, T S 2nd and 4th Saturday No. 2/5, Door No. 5-87-32, Guntur Andhra Pradesh Guntur 9:30 AM - 4:30 PM of each month, Sundays Lakshmipuram Main Road, and Public Holidays Guntur,Andhra Pradesh 522 007 Ground Floor, 2/27/14-2 Koppana 2nd and 4th Saturday Kakinada, Andhra Andhra Pradesh Kakinada Complex, Gokula Street, Sri Nagar, 9:30 AM - 4:30 PM of each month, Sundays Pradesh Kakinada, Andhra Pradesh - 533003. and Public Holidays Ground Floor, No. 7/473-1, Godugu 2nd and 4th Saturday Pet Main Road, Ward No.7, Machilipatnam Andhra Pradesh Machilipatnam 9:30 AM - 4:30 PM of each month, Sundays Machilipatnam, Andhra Pradesh and Public Holidays 521001 Ground Floor, H. No. 9-9-2, New Ward No. 16, Old Ward No. 4, Block 2nd and 4th Saturday Narsaraopet Andhra Pradesh Narasaoropet No. 2, Opp. Angele Talkies, 9:30 AM - 3:30 PM of each month, Sundays Arundalpeta, Narasaraopet, Guntur, and Public Holidays Andhra Pradesh – 522601. -

DBA-VOTING-LIST-2018.Pdf

Sl.No. Name Address Bar Council Bar No. Phone Phone T.U.P. H.No-322/14, Jacubpura, 1 A.L.Sahni P/1007/1983 2 2321473 9313401837 Gurgaon H.No-763-A, Ist Floor, 2 Aakash Aggarwal Block-H, Palam Vihar, P/695/1999 4 9350840785 9910991353 Gurgaon. V.P.O. Dhunela, Post 3 Aakil Ali P/3239/2014 4051 9050300395 9813313823 Office Sohna, Gurgaon H.No-249,Sector-17-A 4 Aarti Bhalla P/2016/2015 4246 9350320004 Gurgaon. H.No-224/7, H.B. 5 Aarti Hans Colony, Sec-7 Ext, P/1398/2011 3061 9910383914 Gurgaon Vill- Udaka, PO-Sohna, 6 Aazad P/3601/2009 2544 9711115701 Distt- Gurgaon Gandhi Nagar Ward No. 7 Abdul Hamid 8 Opp Mewat Model P/778/1994 4054 8860481185 School Tauru. Vill-Rewasan, Teh -Nuh, 8 Abdul Rehman P/95/1998 6 9416256151 9813039030 Distt-Gurgaon PWO Housing Complex, B-2/301, Sector 43, 9 Abha Sinha Sushant Lok-I, Gurgaon P/1800/1999 4751 9871957449 At(P) C-6/6360, Vasant Kunj, New Delhi H.No-645/20, Gali No-6, 10 Abhai singh Yadav P/514/1977 3100 9250171144 Shivji Park, Gurgaon Abhey singh H.No.1434, Sec-15, Part- 0124- 11 P/1132/2001 8 9811198319 Dahima II, Gurgaon. 6568432 Resi-Vill-Dhanwa Pur, Abhey Singh 12 Po-Daulta Bad, Distt- P/857/1995 9 9811934070 Dahiya Gurgaon H.No-209/4, Subhash 13 Abhey Singla P/420/2007 2008 9999499932 9811779952 Nagar, Gur. H.No. 225, sector 15, 14 Abhijeet Gupta P/4107/2016 4757 9654010101 Part-I, Gurgaon. -

Haryana Government Town and Country Planning Department Notification

- 1 - HARYANA GOVERNMENT TOWN AND COUNTRY PLANNING DEPARTMENT NOTIFICATION The 15 November, 2012 No. CCP(NCR)/FDP-2031/GGN-SHN/2012/3543.- In exercise of the powers conferred by sub-section (7) of section 5 of the Punjab Scheduled Roads and Controlled Areas Restriction of Unregulated Development Act, 1963 (Act 41 of 1963) and with reference to Haryana Government, Town and Country Planning Department notification No. CCP(NCR)/DDP-2031/GGN-SHN/2012/2350 dated the 25th July, 2012, the Governor of Haryana hereby publishes the Final Development Plan of Sohna 2031 A.D., after considering the objections and suggestions received on the draft plan, alongwith restrictions and conditions as given in Annexure-A and B proposed to be made applicable to the controlled areas specified in Annexure-„B‟. Drawings 1. Existing Land Use Plan Drawing No. DTP(G)2017/2011 dated the 5th July, 2011 (already published vide Haryana Government, Town and Country Planning Department notification No. CCP(NCR)/DDP- 2031/GGN-SHN/2012/2350 dated the 25th July, 2012). 2. Final Development Plan for Sohna-2031 A.D. Drawing No. DTP (G) 2103/2012 dated the 9th November, 2012. ANNEXURE-A EXPLANATORY NOTE ON THE FINAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2031 A.D. FOR THE CONTROLLED AREAS OF SOHNA INTRODUCTION: In the backdrop of picturesque Aravalli Ranges on its West, Sohna is an important old town. As viewed from the top of the hills, where a tourist/ recreational complex has been developed by the Haryana Tourism, the town amalgamated with its green rural background presents a fascinating scenic beauty. The town is also famous for being blessed with boiling hot sulphur spring in the heart of the town with a temple complex around it. -

19Th Antigen Camp Site W.E.F - 01-12-2020 to 8-12-2020 NAME of NAME of UPHC Total DATE of NAME of Sr.No Sr.No

19th Antigen Camp Site w.e.f - 01-12-2020 To 8-12-2020 NAME OF NAME OF UPHC Total DATE OF NAME OF Sr.No Sr.No. CAMP SITE FOR ANTIGEN CAMP MEDICAL /PHC Site CAMP SUPERVISOR OFFICER 1 1 Haily Mandi Market Near Hanuman Mandir (Haily mandi) 01/12/20 2 2 Haily Mandi Market Under Railway Flyover (Haily Mandi) 02/12/20 3 3 Jatauli Market on Haily Mandi F. Nagar Road (Vill- Jatauli) 03/12/20 4 4 Railway Station Haily Mandi-Pataudi (Vill- Todapur) 04/12/20 Dr. Deepak 1 Haliy Mandi 5 5 Govt. Hospital Haily Mandi (Haily Mandi) 05/12/20 Puri 6 6 Govt. Hospital Haily Mandi (Haily Mandi) 06/12/20 7 7 On JK Filling Petrol Pump (Haily Mandi) 07/12/20 8 8 Near ICICI Bank Pataudi Road Haily Mandi (Vill- Todapur) 08/12/20 1 9 Sushila ki Aganwadi Gali No. 1 Hans Enclave 04/12/20 2 10 Dev ka Ghar Hans Enclave 05/12/20 Dr. Anita 2 Naharpur Rupa 3 11 Shiv Colony Gali No. 1 Near Anita ki Aganwadi 06/12/20 Dr. Amit Sharma 4 12 Near Dharam Kanta Naharpur Roopa 07/12/20 5 13 Sunita Niwas Near Chaupal 08/12/20 1 14 Sub center Baslambi 01/12/20 2 15 PHC Bhangrola 02/12/20 3 16 GRAM Sachiwaley, Aliyar 03/12/20 4 17 Gurgaon 1 Society, Sec 84, Sikanderpur Bada 04/12/20 3 Bhangrola Dr. Shalu 5 18 Sub Center, Kankrola Village 05/12/20 6 19 Kuldep ki Baithak, khawaspur Village 06/12/20 7 20 Shiv Mandir, Tatarpur Village 07/12/20 8 21 Ramsons Society Sec. -

Forest Department, Haryana

FOREST DEPARTME|{T' HARYAI{A O/o PCCF (HoFF), Haryanil) Panchkula Van Bhawan, Plot No. C-18, Sector-06, Panchkula Tele. No. 91 172 2563988 Fax 91 172 2583158 Email ID : No.: D-I-49016213 Dated: 18-06-2020 To, The Registrar, Hon'ble National Green Tribunal, New Delhi. Sub.: In the matter of Sonya Ghosh Vs. State of Haryana & Ors. and Haryali Welfare Society Vs. Union of India & Ors. in OA No. 04/2013 (Suo Moto) (M.A. No. 186t2013,M.A. No. 568/2013, M.A. No.731DA13o M.A. No.7412014, M.A. No.75l2014 & M.A. No. 78712014) and OA No. 2812015 (MA No. 6r./2015). --o-- In reference to subject as stated above, Hon'ble National Green Tribunal vide order dated 23.10.2018 has observed as under: "26. The NotiJication dated 07.05.1992 also refers to the area shown as forest land- According to the State of Haryana itself, the area covered by Notffication under Sections 4 and 5 of the PLPA Act is treated as forest tand by the State. Area covered by PLPA notification is also part of the above table. Moreover, in the judgment of the Hon'ble Supreme Court in M.C. Mehta (supra), after referring to earlier judgment in T.N. Godavarman Thirumulpad Vs. (Inion of India & Ors.2, it was made clear that area covered by the Notification under Sections 4 and 5 of the PLPA Act was to be treated as forest area. 27. In view of above, any construction raised on the forest area or the area otherwise covered by Notification dated 07.05.1992 without permission of the competent authority (after the date of the said Notification) has to be treated as illegal and such forest land has to be restored. -

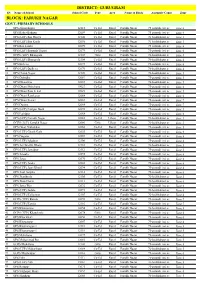

Gurugram Block: Farukh Nagar

DISTRICT: GURUGRAM SN Name of School School Code Type Area Name of Block Assembly Const. Zone BLOCK: FARUKH NAGAR GOVT. PRIMARY SCHOOLS 1 GPS Alimudinpur 12115 Co-Ed Rural Farukh Nagar 75-pataudi (sc) ac Zone 6 2 GPS Babra Bakipur 12089 Co-Ed Rural Farukh Nagar 75-pataudi (sc) ac Zone 4 3 GPS (LEP) Bas Hariya 12100 Co-Ed Rural Farukh Nagar 76-badshahpur ac Zone 3 4 GPS (LEP) Bas Kusla 12098 Co-Ed Rural Farukh Nagar 76-badshahpur ac Zone 3 5 GPS Bas Lambi 12099 Co-Ed Rural Farukh Nagar 75-pataudi (sc) ac Zone 6 6 GPS (LEP) Basunda Tirpari 12079 Co-Ed Rural Farukh Nagar 75-pataudi (sc) ac Zone 6 7 GGPS (LEP) Bhangrola 12103 Girls Rural Farukh Nagar 76-badshahpur ac Zone 4 8 GPS (LEP) Bhangrola 12104 Co-Ed Rural Farukh Nagar 76-badshahpur ac Zone 4 9 GPS Birhera 12073 Co-Ed Rural Farukh Nagar 75-pataudi (sc) ac Zone 6 10 GPS (LEP) Budhera 12070 Co-Ed Rural Farukh Nagar 76-badshahpur ac Zone 4 11 GPS Chand Nagar 12109 Co-Ed Rural Farukh Nagar 76-badshahpur ac Zone 5 12 GPS Dabodha 12081 Co-Ed Rural Farukh Nagar 75-pataudi (sc) ac Zone 5 13 GPS Dhanawas 12057 Co-Ed Rural Farukh Nagar 76-badshahpur ac Zone 5 14 GPS Dhani Mehchana 19027 Co-Ed Rural Farukh Nagar 75-pataudi (sc) ac Zone 6 15 GPS Dhani Ram Ji Lal 19029 Co-Ed Rural Farukh Nagar 75-pataudi (sc) ac Zone 5 16 GPS Dhani Ramkaran 12088 Co-Ed Rural Farukh Nagar 75-pataudi (sc) ac Zone 6 17 GPS Dhani Siwari 12053 Co-Ed Rural Farukh Nagar 75-pataudi (sc) ac Zone 7 18 GPS Dooma 12064 Co-Ed Rural Farukh Nagar 75-pataudi (sc) ac Zone 7 19 GPS (LEP) Fajilpur Badli 12090 Co-Ed Rural Farukh Nagar -

List of Colonies in Villages

Circle rates – Gurgaon from April 1, 2010 onwards LIST OF COLONIES IN VILLAGES Name Year 2010-2011 Residential Commercial 1. Babupur 3500 9000 2. Badshahpur 4800 12000 3. Bajghera 3500 9000 4. Basai 5500 12000 5. Chakkarpur 6500 17000 6. Chauma 4000 9000 7. Dhanwapur 3500 9000 8. Dundahera 6500 18000 9. Garhi Harsaru 2400 9000 10. Gurgaon Village 6500 22000 11. Islampur 6000 13000 12. Jharsa Village 6500 15000 13. Kanhai 6500 15000 14. Kadipur 6000 13000 15. Khandsa 6000 16000 16. Karterpuri 6500 13000 17. Narsing Pur 6000 16000 18. Nathupur 6500 17000 19. Naharpur Roopa 6000 17000 20. Molahera 6500 17000 21. Pawala Khusrupur 3500 11000 22. Sarhaul 6500 16000 23. Samaspur 6500 15000 24. Tikri 4500 9500 25. Tigra 6000 11000 26. Virendra Gram 5500 8500 As is information. Shared as received. You may recheck with competent authority before conducting the transaction. We will not be responsible for the correctness of the content 27. Wazirabad 6500 15000 REVISED RATES FOR AGRICULTURE LAND & PLOT FOR YEAR 2010-11 Name Year 2010-2011 All Type of Land Gair Mumkin Plot 1. Aklimpur 3500000 1900 2. Adampur 12000000 6500 3. Sarai Alwardi 6000000 5500 4. Bindapur 12000000 6500 5. Bashariya 6000000 3500 6. Banskusla 6000000 3500 7. Begampur Khatola 8000000 4000 8. Badshahpur 8000000 4800 9. Behrampur 8000000 3500 10. Bajghera 6700000 ------ 11. Babupur 6700000 ------ 12. Budhera 3000000 1900 13. Basai 6700000 ------ 14. Bamrouli 6700000 3500 15. Bhangroula 6700000 3500 16. Chakkarpur 12000000 ------ 17. Chauma 7800000 ------ 18. Chandu 3000000 1700 19. Dhorka 6700000 3000 20. Dhana 6700000 3500 21.