Supporting Figure 1. Heat Map analysis of the first 30 bacterial families detected using 16S rRNA gene-based 454 sequencing among CF patient sputum samples. The families in red are those that were successfully cultured at least once during the study. The presence/absence plot shows the bacteria detected in each of the sputum samples. The average copy number per positive sample for each detected bacterial family is shown on the far right.

Supporting Figure 2. Analysis using ClustalW predicted amino acid sequences of PA1396 from clinical isolates of P. aeruginosa. The alignment displays the degree of conservation observed between each of the sequences.

Supporting Figure 3. RT-PCR analysis of the effects of DSF addition to selected P. aeruginosa clinical isolates on transcript levels for PA4774 (black bars) and PA4776 (grey bars). Data were normalized to 16S RNA and each is presented as the fold change with respect to the wild-type P. aeruginosa for each gene. Data (means ± SD) are representative of three independent biological experiments.

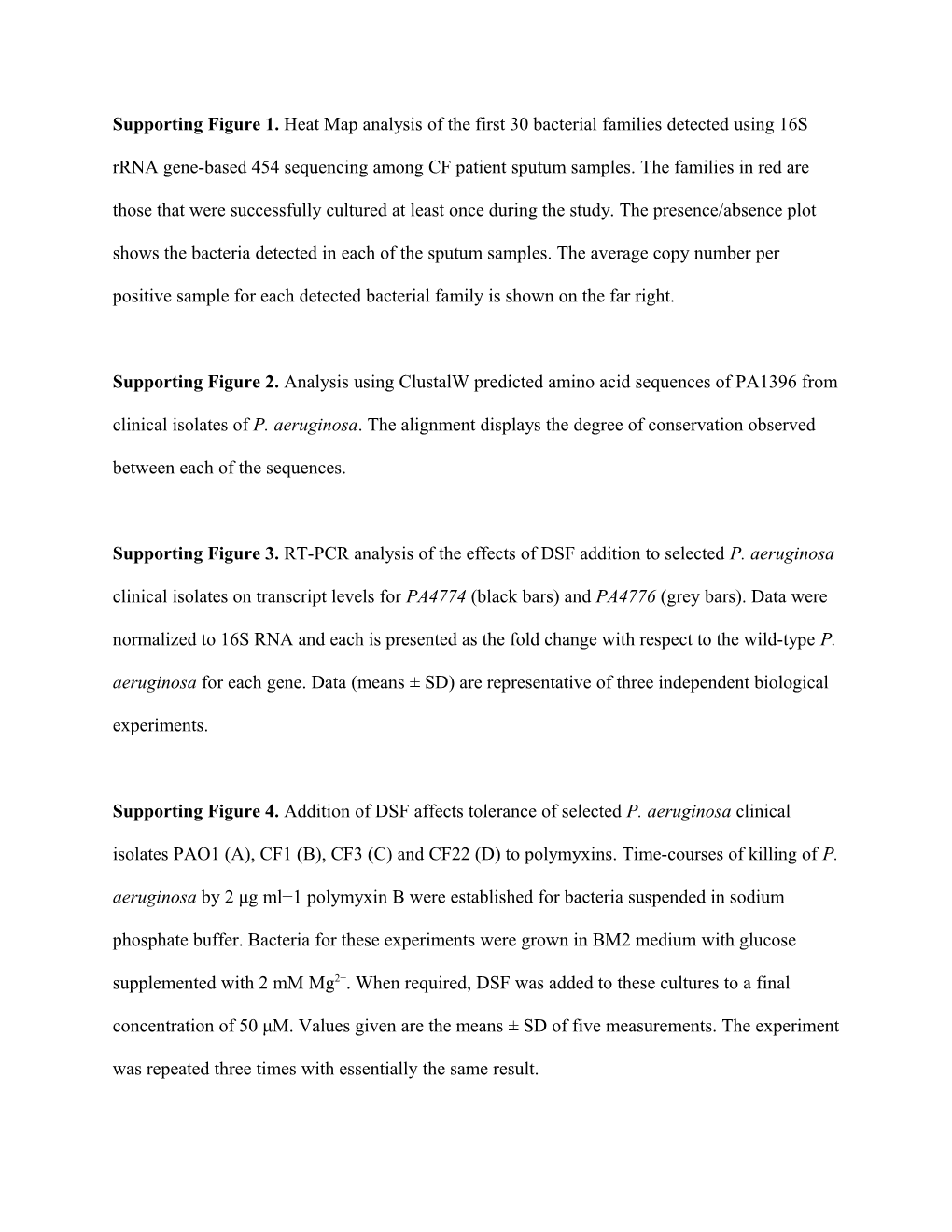

Supporting Figure 4. Addition of DSF affects tolerance of selected P. aeruginosa clinical isolates PAO1 (A), CF1 (B), CF3 (C) and CF22 (D) to polymyxins. Time-courses of killing of P. aeruginosa by 2 μg ml−1 polymyxin B were established for bacteria suspended in sodium phosphate buffer. Bacteria for these experiments were grown in BM2 medium with glucose supplemented with 2 mM Mg2+. When required, DSF was added to these cultures to a final concentration of 50 μM. Values given are the means ± SD of five measurements. The experiment was repeated three times with essentially the same result. Supporting Figure 5. Mutation of PA1396 affects tolerance to polymyxins in clinical isolates of

P. aeruginosa PAO1 (A), CF3 (B), CF9 (C) and CF14 (D). Time-courses of killing of P. aeruginosa by 2 μg ml−1 polymyxin B were established for bacteria suspended in sodium phosphate buffer. Bacteria for these experiments were grown in BM2 medium with glucose supplemented with 2 mM Mg2+. Values given are the means ± SD of five measurements. The experiment was repeated three times with essentially the same result.

Supporting Figure 6. Mutation in PA1396 leads to enhanced persistence and dissemination of

P. aeruginosa in mice. C57BL/6 or CF mice were infected with wild type PAO1 or the PA1396 mutant. Animals were sacrificed at 1, 3, 5, 7 days after infection and 10-fold serial dilutions of lung (A and B) and spleen (C and D) homogenates were plated to determine the bacterial load.

The means and standard deviations of triplicate measurements are shown.

Supporting Figure 7. Real-time RT-PCR analysis of the effects of addition of DSF or trans-11- methyl dodecenoic on transcript levels for PA1709, PA1710, PA1714, PA4599, PA4774,

PA4775, PA4776 and PA4781. Data were normalized to 16S RNA and each is presented as the fold change with respect to the wild-type P. aeruginosa PAO1 for each gene. Data (means ± SD) are representative of four independent biological experiments. Black columns: effects of addition of 50 μM DSF; grey columns: effects of addition of 50 μM trans-11-methyl dodecenoic.

Supporting Figure 8. RT-PCR analysis of the effect mutation of PA1396 on transcript levels for

PA0806, PA0901, PA1560, PA2966, PA4358, PA4359, PA4599, PA4774, PA4775, PA4776 and PA5505. Data were normalized to 16S RNA and each is presented as the fold change with respect to the wild-type P. aeruginosa PAO1 for each gene. Data (means ± SD) are representative of four independent biological experiments.

Supporting Table 1. Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

Supporting Table 2. Sampling depth and biodiversity found by barcoded 454 sequencing of sputum samples from the 40 CF patients and the 10 patients with viral-induced bronchitis.