Perspectives on Politics (forthcoming, March, 2010) 1

Changing Mass Priorities: The Link between Modernization and Democracy

RONALD INGLEHART University of Michigan

CHRISTIAN WELZEL Jacobs University Bremen

Introduction. Rich countries are much likelier to be democracies than poor countries. Why this is true is debated fiercely. Simply reaching a given level of economic development could not itself produce democracy; it can do so only by bringing changes in how people act. Accordingly, Seymour Martin Lipset (1959) argued that development leads to democracy because it produces certain socio-cultural changes that shape human actions. The empirical data that would be needed to test this claim did not exist then, so his suggestion remained a passing comment.1 Today, large-N comparative surveys make the relevant data available for most of the world’s population, and there have been major advances in analytic techniques. But social scientists rarely put the two together, partly because of a persisting tendency to view mass attitudinal data as volatile and unreliable. In this piece we wish to redress this situation. We argue that certain modernization-linked mass attitudes are stable attributes of given societies that are being measured reliably by the large-N comparative survey projects, even in low-income countries, and that these attitudes seem to play important roles in social changes such as democratization. Our purpose here is not to demonstrate the impact of changing values on democracy so much as to make a point about the epistemology of survey data with important ramifications for the way we analyze democracy. Unlike dozens of articles we’ve published that nail down one hypothesis about one dependent variable, this piece analyzes data from almost 400 surveys to demonstrate that modernization-linked attitudes are stable attributes of given societies and are strongly linked with many important societal-level variables, ranging from civil society to democracy to gender equality. Direct measures of these attitudes enable us to test arguments about the role of culture, such as Lipset’s assumption that economic development leads to democracy by changing people’s goals and behavior. In this regard, our argument is relevant to all scholars interested in explaining the sources of democratization. Why are economic development and democracy so strongly correlated? A century and a half ago, Karl Marx argued that industrialization brings the rise of the bourgeoisie which brings democracy. Karl Deutsch (1964) argued that urbanization, industrialization and rising mass literacy transform geographically scattered and illiterate peasants into participants who become increasingly able to play political roles. But

1 More recently, using state of the art econometric techniques, Acemoglu and Robinson also conclude that both economic development and democracy reflect deep-rooted institutional/cultural factors. Perspectives on Politics (forthcoming, March, 2010) 2 representative democracy is only one possible outcome. As Barrington Moore Jr., (1966) noted long ago, industrialization can lead to fascism, communism or democracy. The evidence underlying this earlier work was largely illustrative. Recent research employing quantitative analysis has been done by Boix, (2003), Przeworski et al. (2000) and others, but Acemoglu and Robinson’s work (2000, 2001, 2006; cf. Robinson, 2006), may be the most advanced methodologically.2 And it suggests that institutional and cultural factors play crucial roles. Using new sources of data, Acemoglu and Robinson attempt to determine whether economic development leads to democracy, or whether democratic institutions lead to economic growth. They conclude that neither causal path holds up: both economic development and democracy can be attributed to “fixed national effects,” which reflect a society’s entire historical, institutional and cultural heritage. This suggests that cultural variables (deeply-instilled mass attitudes) might play an important role in democratization-- but they remain lumped together with many other things. Evidence in this article indicates that a given society’s institutional and cultural heritage is remarkably enduring. But in order to analyze its impact, one needs direct measures of certain mass orientations. Today, the large-N comparative surveys provide empirical measures of key attitudinal variables for almost 90 percent of the world’s population. As we will demonstrate, certain mass orientations are powerful predictors of a society’s level of democracy. They provide the missing link between economic change and democratization. Nevertheless, they are rarely used in econometric analysis. Why? (1) One reason is a tendency to omit mass publics from models, viewing democratization as simply a matter of elite bargaining. (2) Another reason is a tendency to view subjective mass orientations as volatile factors that are not stable attributes of given societies. In addition, (3) the models cited above assume that mass demand for democracy is a constant that can’t explain changes such as democratization. Or (4) if it is recognized that mass demand for democracy does vary, it is claimed that democratic institutions give rise to pro-democratic mass attitudes, not the other way around. Mass attitudes are assumed to be either irrelevant or too unstable to shape democratization. As we will argue, these assumptions are false: during the decades before 1990, mass emphasis on democracy became increasingly widespread in many authoritarian societies, and contributed to their subsequent downfall. Many survey variables are unstable. Presidential popularity varies dramatically from week to week. But as this article demonstrates (1) certain modernization-linked mass orientations are fully as stable as standard social indicators; (2) using national-level mean scores on these variables is justifiable on both methodological and theoretical grounds; (3) these attitudes have strong predictive power with important societal-level variables such as democracy. But before demonstrating these claims, let us outline the theory that points to them, expanding upon a revised version of modernization theory that has generated a sizeable body of literature3 (Inglehart, 1997; Inglehart and Baker, 2000;

2 We do not discuss the large and flourishing literature on democratization in this brief overview of that and nine other dependent variables. For a discussion of how the democratization literature relates to our thesis, see Inglehart and Welzel (2005) and Haerpfer, Bernhagen, Inglehart and Welzel (2009). Perspectives on Politics (forthcoming, March, 2010) 3

Welzel, Inglehart and Klingemann, 2003; Norris and Inglehart, 2004; Inglehart and Welzel, 2005; Welzel and Inglehart, 2008, 2009).

Modernization: a revised view Modernization theory needs to be revised for several reasons. First, modernization is not linear, moving indefinitely in the same direction. Industrialization leads to one major process of change, bringing bureaucratization, hierarchy, centralization of authority, secularization, and a shift from traditional to secular-rational values. But the postindustrial phase of modernization brings increasing emphasis on individual autonomy and self-expression values, which erode the legitimacy of authoritarian regimes and make effective democracy increasingly likely to emerge. The process is not deterministic; a given country’s leaders and nation-specific events also matter. Moreover, modernization’s changes are not irreversible. Economic collapse can reverse them, as happened during the Great Depression in Germany, Italy, Japan, and Spain-- and during the 1990s in most Soviet successor states. Second, socio-cultural change is path dependent. Although economic development tends to bring predictable changes in people’s worldviews, a society’s religious and historic heritage leaves a lasting imprint. Although the classic modernization theorists thought that religion and ethnic traditions would die out, they were wrong. Third, modernization is not Westernization, contrary to early ethnocentric concepts. The process of industrialization began in the West, but during the past few decades East Asia has had the world’s highest economic growth rates and Japan leads the world in life expectancy. Fourth, modernization does not automatically bring democracy. Industrialization can lead to fascism, communism, theocracy or democracy. But postindustrial society brings socio-cultural changes that make truly effective democracy increasingly probable. Knowledge societies cannot function effectively without highly-educated workers, who become articulate and accustomed to thinking for themselves. Furthermore, rising levels of economic security bring growing emphasis on self-expression values that give high priority to free choice. Mass publics become increasingly likely to want democracy, and increasingly effective in getting it. Repressing mass demands for liberalization becomes increasingly costly and detrimental to economic effectiveness. These changes link economic development with democracy. The core concept of modernization theory is that economic development produces systematic changes in society and politics. If so, one should find pervasive differences between the beliefs and values of people in low-income and high-income societies. The World Values Survey and European Values Study (henceforth referred to as the WVS/EVS)4 provide evidence that the transition from agrarian to industrial society produces one set of changes, and the rise of postindustrial societies produces another set

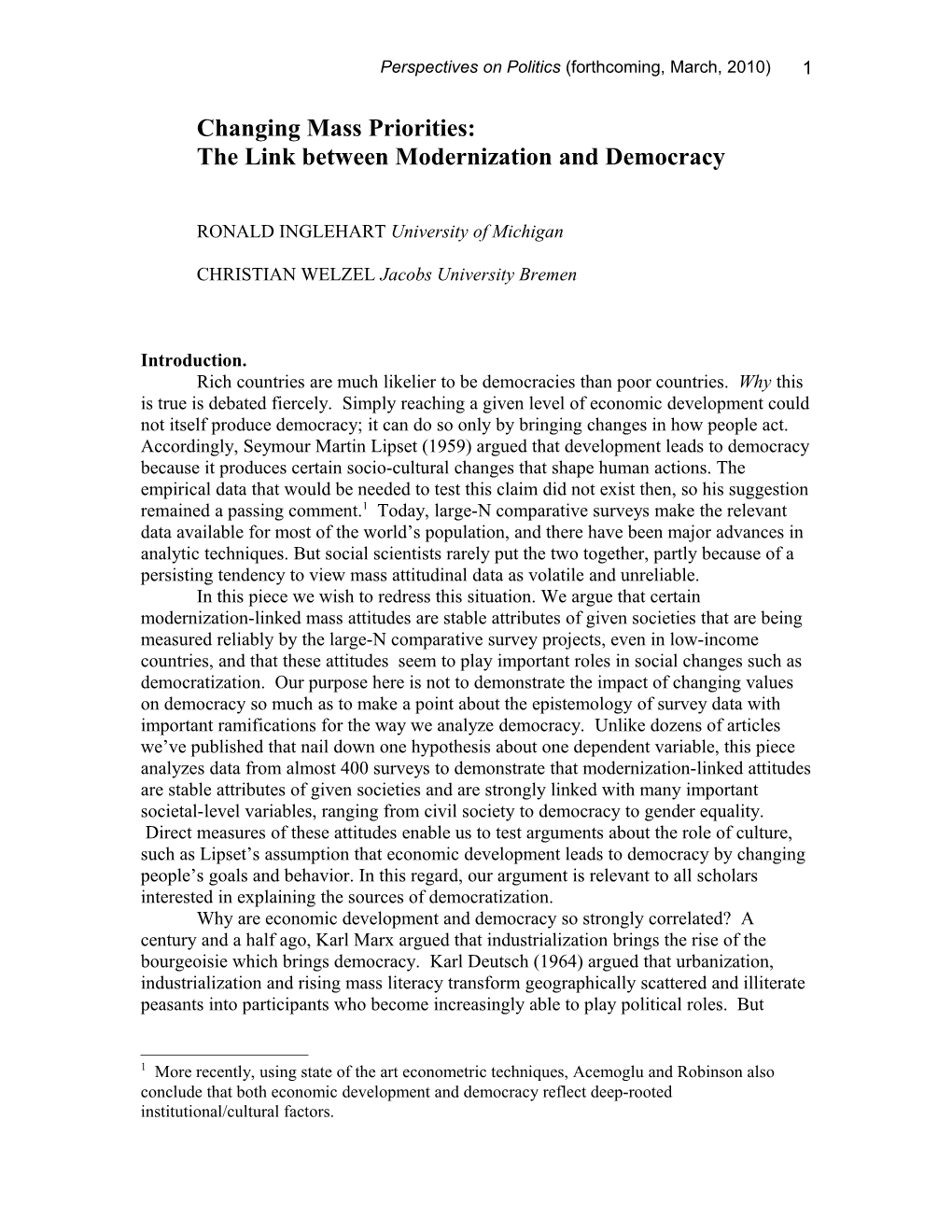

3 The two-dimensional global map of cross-cultural differences derived from this work has appeared in at least a dozen political science, sociology and cultural anthropology textbooks. 4 Both the WVS and the EVS grew out of the 1981 EVS and the two groups collaborated in their 1990-1991 and 1999-2001 waves. For an excellent account of the evolution of the large-N comparative survey programs, see Norris, 2009. Perspectives on Politics (forthcoming, March, 2010) 4 of changes in peoples’ values and motivations. Analyses of WVS/EVS data reveal two major dimensions of cross-cultural variation: (1) a traditional versus secular-rational values dimension and (2) a survival versus self-expression values dimension. These two dimensions tap scores of attitudinal variables, and are robust enough that one obtains similar results using various combinations of these variables.5 Theoretically, the Traditional/Secular-rational dimension reflects changes linked with the transition from agrarian to industrial society, associated with bureaucratization, rationalization, and secularization. Accordingly, the publics of agrarian societies emphasize religion, national pride, obedience and respect for authority, while the publics of industrial societies emphasize secularism, cosmopolitanism, autonomy, and rationality. With the emergence of postindustrial society, unprecedented levels of prosperity plus the welfare state bring high levels of existential security. When survival is insecure, it tends to dominate people’s life strategies. But the younger birth cohorts of these societies have grown up taking survival for granted, allowing other goals to become more prominent. This trend is reinforced by the fact that in knowledge societies, one’s daily work requires individual judgment and innovation, rather than following routines prescribed from above. Both factors bring increasing emphasis on self-expression. The survival versus self-expression dimension reflects polarization between emphasis on order, economic security, and conformity-- versus emphasis on self-expression, participation, subjective well-being, trust, tolerance, and quality of life concerns. In recent decades the publics of virtually all rich countries have gradually moved toward increasing emphasis on self-expression values, but the relative positions of given countries were remarkably stable. Thus, Survival/Self-expression values and Traditional/Secular-rational values show autocorrelations of .95 and .92 across successive waves of the WVS/EVS. The mean autocorrelation for their ten indicators is .88. This is comparable to the stability of standard social indicators such as GDP/capita or democracy measures. Factor analysis of data from the 43 societies in the 1990 WVS/EVS found that these two dimensions accounted for over half of the cross-national variance in scores of variables (Inglehart 1997). When this analysis was replicated with data from the 1995- 1998 surveys, the same two dimensions emerged—although the new analysis included 23 additional countries (Inglehart & Baker 2000). The same two dimensions emerged in analysis of data from the 2000-2001 surveys (Inglehart & Welzel 2005). Figure 1 about here Figure 1 shows the locations of 52 countries on these two dimensions, using the data from the 2005-2007World Values Survey. Comparing this cultural map with the map based on the 1999-2001 surveys, one might think they are the same.6 Actually, Figure 1 is based on new surveys, including 13 new countries and dropping several other

5 For technical reasons, later work derived the dimensions from ten of these variables. The resulting cross-cultural map is so robust that, using a completely different way of measuring basic values, different types of samples and a different type of dimensional analysis, Schwartz (2006) finds very similar transnational groupings among 76 countries. 6 Compare the map based on the1999-2001 data at http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org. Also see the 1995 map in Inglehart and Baker (2000), p. 29 and the 1990 map in Inglehart (1997), p. 98. The similarity of the four maps, based on data from different sets of surveys, is striking. Perspectives on Politics (forthcoming, March, 2010) 5 countries. Relative scores on these two dimensions have been stable attributes of given countries throughout the period from 1981 to 2007. Our revised version of modernization theory holds that rising levels of existential security are conducive to a shift from traditional values to secular-rational values, and from survival values to self-expression values. Accordingly, virtually all of the high- income countries rank high on both dimensions, falling into the upper-right region of the chart-- while virtually all of the low and lower-middle-income countries rank low on both dimensions, falling into the lower-left region of the chart. But the evidence also supports the Weberian view that a society’s religious values leave a lasting imprint. The publics of Protestant Europe show relatively similar values across scores of questions—as do the publics of Catholic Europe, the Confucian- influenced societies, the Orthodox societies, the English-speaking countries, Latin America, and sub-Saharan Africa.7 The cross-national differences found in the large-N surveys reflect each society’s economic and socio-cultural history. 2.0 Japan Sweden E.Germany 1.5 Confucian W.Germany Protestant Taiwan Hong Kong Norway Europe

s e

u 1.0 l Bulgaria Finland a Slovenia V Netherlands China Switzerland l

a Hungary n S.Korea France o

i 0.5 t Serbia Catholic Europe a Russia Moldova

R Australia - Italy

r Ukraine a

l Orthodox

u 0.0 Britain c Spain N.Zealand e S

South . Canada s Romania v Asia l Vietnam Cyprus a English -0.5 India Uruguay n Iraq

o Thailand

i Indonesia Speaking

t Argentina

i Ethiopia Poland

d Malaysia a Zambia U.S. r Turkey Latin T -1.0 Chile Brazil America Africa Burkina F Mali Rwanda Mexico -1.5 Morocco S. Africa Guatemala 1 standard Egypt Colombia deviation Ghana Trinidad -2.0 -2.0 -1.5 -1.0 -0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0 Survival vs. Self Expression Values Figure 1. Locations of 53 societies on global cultural map in 2005-2007.

7 At first glance, these clusters might seem to reflect geographic proximity, but closer examination indicates that this is only true when geographic proximity coincides with cultural similarity. Thus, the English-speaking zone extends across Europe to North America and Australia, while the Latin American zone extends from Tiajuana to Patagonia, and an Islamic subgroup within the African and South Asian clusters locates Morocco relatively near Indonesia, though they are on opposite sides of the globe. Perspectives on Politics (forthcoming, March, 2010) 6

Source: Data from World Values Survey Perspectives on Politics (forthcoming, March, 2010) 7

Cross-national differences are huge. Thus, the proportion saying that God is very important in their lives ranges from 98 percent in relatively traditional countries to 3 percent in secular-rational countries.8 Cross-national differences dwarf the differences within given societies. The ellipse in the lower right-hand corner of Figure 1 shows the size of the average standard deviation within given countries.9 It occupies a tiny fraction of the map. Two-thirds of the average country’s respondents fall within one standard deviation of their country’s mean score on both dimensions and 95 percent fall within two standard deviations. Despite globalization, nations remain an important unit of shared experiences, and the predictive power of nationality is much stronger than that of income, education, region or sex. Is it justifiable to use national-level mean scores on these variables as indicators of societies’ attributes? One can imagine a world in which everyone with a university- level education had modern values, placing them near the upper right-hand corner of the map-- while everyone with little or no education clustered near the lower left-hand corner of the map. We would be living in a global village where nationality meant nothing. Perhaps some day the world will look like that, but empirical reality today is very different. Thus, Italy is at the center of Figure 1, near Spain but a substantial distance from most other societies. Although individual Italians can fall anywhere on the map, there is surprisingly little overlap between the prevailing orientations of large groups of Italians and their peers in other countries: most nationalities are at least one or two standard deviations away from the Italians. The same holds true of Slovenians, Norwegians, Mexicans, Americans, Russians, British and other nationalities. Figure 2 about here Figure 2 further illustrates this fact, showing the positions of university-educated respondents and the rest of the sample, in the two most populous countries from each cultural zone (the arrow moves from the less-educated to the university-educated group). The basic values of most highly-educated Chinese are quite distinct from those of highly- educated Japanese, and even farther from those of other nationalities. Highly-educated Americans do not overlap much with their European peers; their basic values are closer to those of less-educated Americans. Even today, the nation remains a key unit of shared socialization, and in multiple regression analyses, nationality explains far more of the variance in these attitudes than does education, occupation, income, gender or region. Figure 3 about here When we compare the basic values of urban and rural respondents, the tendency for between-societal differences to dominate within-societal differences is considerably stronger. And though the values of men and women differ, the dominance of between- societal differences is even stronger here, as Figure 3 indicates. Basic values vary far more between societies than within them, and in global perspective a given society’s men and women have relatively similar values. The cross-national differences are so much larger than the within-societal ones that in global perspective, even findings from imperfect samples tend to be in the right ball park.

8 This item is one of the indicators of the Traditional/Secular-rational values dimension. 9 The average standard deviation on the traditional vs. secular-rational dimension is smaller than the average standard deviation on the survival vs. self-expression dimension, making the figure an ellipse rather than a circle. Perspectives on Politics (forthcoming, March, 2010) 8

Modernization-linked attitudes tend to be enduring and cross-nationally comparable Certain types of modernization-linked attitudes constitute stable attributes of given societies that are fully as stable as per capita GNP. This is not true of all attitudinal variables. Perspectives on Politics (forthcoming, March, 2010) 9

Japan 2.0 W. Germany

1.5 China

s e u l a V

l 1.0

a Netherlands

n Russia o i t a R - 0.5 France r

a Ukraine l u c

e Britain

S Italy 0.0 . s v

l

a Turkey n o i

t -0.5

i India d a

r U.S.

T Brazil Indonesia Ethiopia -1.0 Mali Rwanda Mexico -1.5 S. Africa

-2.0 -2.0 -1.5 -1.0 -0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0 Survival vs. Self Expression Values

Figure 2. Locations of university-educated vs. rest of sample on global cultural map, 2005-2007 (arrow runs from less-educated to university-educated respondents).

2.0 Japan

W. Germany 1.5 s e u l a V

l 1.0 a

n Netherlands o i t China a R - 0.5 France r Russia a l

u Britain c

e Italy S

Ukraine

. 0.0 s v

l a

n India o i

t -0.5 i Indonesia d a

r U.S.

T Brazil Ethiopia -1.0 Mali Mexico

-1.5 Rwanda S. Africa

-2.0 -2.0 -1.5 -1.0 -0.5 0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5 3.0 Survival vs. Self Expression Values

Figure 3. Location of male vs. female respondents on global cultural map, 2005-2007 (arrow runs from male to female respondents). Perspectives on Politics (forthcoming, March, 2010) 10

Most of them tap transient orientations that could not be used as social indicators. But the forces of modernization have impacted on large numbers of societies in broadly comparable ways. Urbanization, industrialization, rising educational levels, occupational specialization and bureaucratization produce enduring changes in people’s worldviews. They do not make all societies alike, but they do tend to make societies that have experienced them, differ from societies that have not experienced them, in consistent ways. For example, modernization tends to make religion less influential. Specific religious beliefs vary immensely, but the worldviews of people for whom religion is important, differ from those for whom religion is not important, in remarkably consistent ways. Consequently, the beliefs and values linked with modernization have more cross- national similarity than most other attitudes, reducing problems of translation and differential item functioning. Critics have argued against aggregating individual-level attitudes, citing the ecological fallacy as if it meant that aggregating individual-level data to the societal-level is somehow tainted (Seligson, 2002). This interpretation is mistaken. Almost 60 years ago, in his classic article on the ecological fallacy, Robinson (1950) pointed out that the relationships between two variables at the aggregate level, are not necessarily the same as those at the individual level. This is an important insight, and it applies fully as much to objective social and economic indicators as it does to attitudinal data. But it does not mean that aggregating is wrong. It simply means that one can not assume that a relationship that holds true at one level also holds true at another level. Social scientists have been aggregating objective individual-level data to construct national-level indices such as per capita income or mean fertility rates for so long that they seem familiar and legitimate—but they are no more legitimate than aggregated subjective data. National means tell only part of the story. Measures of variance and skew are also informative. But having examined them, we conclude that for present purposes, the most significant aspect of subjective orientations are the differences in national-level means. As mentioned, certain modernization-linked attitudes show high national-level stability within the WVS/EVS surveys. Now let us use an even more demanding test of cross-national reliability, examining whether questions about these orientations produce similar results not only within the same survey program, but across surveys carried out at different times, by different large-N survey programs— sometimes using different measuring scales. If similar cross-national pattern emerge under these circumstances, the measures are truly robust. Let’s start by comparing responses to identical questions from the WVS/EVS and the European Social Survey (ESS).10 Figure 4 about here The publics of 22 societies surveyed in both the WVS/EVS and the ESS were asked how often they attend religious services. Figure 4 shows the percentage saying “never” or “practically never.” The results from the WVS/EVS surveys conducted in

10 A number of other items asked questions used in the WVS, but used different response categories—for example, using an 11-point scale instead of four categories. Such differences in formulation can have a large impact on the responses, weakening comparability but not destroying it completely. We will compare some of the findings below. Perspectives on Politics (forthcoming, March, 2010) 11

199911 correlate almost perfectly with those from the 2002 ESS surveys: r = .97. The mean difference between the WVS/EVS results and the ESS result is only 3.5 percentage points. Since random probability surveys generally have sampling error margins about this large, the results from the WVS/EVS and ESS surveys are effectively identical.

Figure 4. European Social Survey and World Values Survey results: % Never attend Religious Services 60 Czech

Netherlands

s France 50 e

c Britain i v

r Belgium e

S Luxembourg

s

u 40 Denmark o Sweden i

g Germany i

l Hungary

e Spain Norway R

d Estonia n

e 30 t t Switzerland A Austria

r

e Finland v e

N Portugal Slovenia 20 %

) 2

0 Italy 0 2 (

S

S 10 E Ireland

Greece

Poland 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 WVS (1999-2001) % Never Attend Religious Services N = 22 r = .97

11 Norway, Switzerland and Greece were surveyed in 1995. Perspectives on Politics (forthcoming, March, 2010) 12

This remarkable similarity of results from two different survey programs is no fluke. Both programs asked another almost identical question about how often people pray. The responses of the various publics again were very similar, correlating at r = .91. Here, the WVS/EVS results varied from the 2002 ESS results by a mean of only 2.2 points. The two programs asked a number of other questions about religion, without using identical wording or response scales. Since they used different scales the levels are not comparable, but the countries’ relative positions are very similar. Across 20 pairs of questions, the correlations have a mean of .88. Although the questions weren’t identical and the surveys were carried out several years apart, questions concerning the importance of religion in the two programs produced remarkably similar cross-national patterns. Figure 5 about here Another modernization-linked orientation, interpersonal trust, also shows high cross-program stability.12 The responses from ESS surveys in twenty-one European societies and Afrobarometer surveys in seven African societies correlate with those from the WVS/EVS surveys in the same societies at r = .92, despite using different scales and several years elapsing between surveys. Figure 6 about here The ISSP operates on several continents, making it possible to compare findings with the WVS/EVS across a wide range of settings. Figure 6 shows the percentages of 18 publics saying they never pray13 The results from the two programs are almost identical (r = .96). Life satisfaction is another relatively stable modernization-linked orientation. The WVS/EVS and the Gallup World Poll asked, in the same 97 countries: “All things considered, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days?” As Figure 7 indicates, although the WVS/EVS used a 1 to 10 scale and the Gallup scale ranged from 0 to 10,14 the results are strikingly similar, showing an overall correlation of r = .94.

12 The WVS/EVS employed two response categories: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted, or do you need to be very careful?” The ESS used an 11-point scale. The Afrobarometer surveys asked the same question with four response categories. Figure 5 shows the percentage of respondents falling in the upper half of each scale. 13 The questions differed slightly, asking if you “Never pray to God” (the WVS/EVS formulation) or “Never pray” (ISSP formulation). 14 Jordan is a rare exception that scores higher on the 0-10 scale than on the 1-10 scale; Ghana deviates in the opposite direction. It would be impractical to show labels for all 97 societies on this figure, so we have labelled only some extreme cases plus the U.S The following countries were included in both surveys: Albania, Algeria, Andorra, Argentina, Armenia, Australia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia, Brazil, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Canada, Chile, China, Colombia, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Dominican Republic, Egypt, El Salvador, Estonia, Ethiopia, Finland, France, East Germany, Georgia, Ghana, Great Britain, Greece, Guatemala, Hong Kong, Hungary, Iceland, India, Indonesia, Iran, Iraq, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Jordan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Malaysia, Mali, Malta, Mexico, Montenegro, Moldova, Morocco, N. Ireland, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nigeria, Norway, Pakistan, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Rwanda, South Africa, South Korea, Saudi Arabia, Serbia, Singapore, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan, Tanzania, Thailand, Trinidad and Tobago, Turkey, Uganda, Perspectives on Politics (forthcoming, March, 2010) 13

Figure 7 about here 75

Denmark 70 Finland

65

) Sweden I I I

60 r Netherlands e t

e 55

m Ireland o r 50 a b o r f 45 UK A Spain &

40 I I

I Belgium Luxemb. Germany (W.) S 35 S

E Italy (

e 30 France

l Czech R. p Cyprus Russia o

e 25 Slovenia Greece P Portugal

n Mali Hungary i

20 Bulgaria t s Poland u Ghana r 15 T Uganda Zimbabwe Nigeria Zambia 10 Tanzania 5 r = .92***

0 0 5 10 15 20 25 30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 Trust in People (WVS IV & V)

Figure 5. Interpersonal trust levels as measured by the World Values Survey and European Values Study, and the European Social Survey and Afrobarometer Survey.

Ukraine, Uruguay, U.S.A., Venezuela, Vietnam, West Germany, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Perspectives on Politics (forthcoming, March, 2010) 14

Figure 6. International Social Survey Program and World Values Survey results: percentage who Never Pray

70 East Germany

60 Russia Czech y

a 50 r P r e v e Netherlands

N 40 Bulgaria %

) 8

9 Hungary Britain

9 Spain 1

( 30

P West

S Germany S I Canada

20 Austria Northern Ireland Italy U.S.A. Japan 10 Poland Ireland

Philippines 0 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 WVS (1999-2001) % Never Pray to God N = 18 r = .96 Perspectives on Politics (forthcoming, March, 2010) 15

8.50 Denmark 8.00

7.50 U. S. A.

7.00 7

0 6.50 0 2

, l l 6.00 o Ghana

P Jordan

d

l 5.50 r o W 5.00 p u l l

a 4.50 G

4.00

3.50 N = 97, r = .94 3.00 Zimbabwe 3.50 4.00 4.50 5.00 5.50 6.00 6.50 7.00 7.50 8.00 8.50 Values Surveys, 1995 - 2007

Figure 7. 2007 Gallup World Poll, and 1995 – 2007 WVS/EVS results: Mean score on overall life satisfaction scales. N = 97 r = .94

Linkages with societal-level variables Our theory holds that economic development leads to growing emphasis on self- expression values-- a syndrome of trust, tolerance, political activism, support for gender equality and emphasis on freedom of expression, all of which are conducive to democracy. This implies that rising emphasis on self-expression values should be closely correlated with: (a) economic development and (b) civil society, citizen participation and democracy. To test these hypotheses, one would ideally analyze data from societies covering the full range of economic development and democracy. But most poor or authoritarian countries lack a well developed survey research infrastructure so the margin of error may be higher. If one’s sole priority were methodological purity, one would limit research to rich democracies. Nevertheless, some large-N projects attempt to cover the full range of variation in economic and political variation. Doing so enhances one’s analytic leverage. Moreover, bringing survey research into low-income countries helps them develop their survey research capabilities, an important contribution to capacity building. The Afrobarometer program and the WVS have emphasized long-term collaboration with social scientists in developing countries, producing numerous joint publications. Is it possible to obtain Perspectives on Politics (forthcoming, March, 2010) 16 accurate data from low-income societies? Or is the error margin so large as to render the data useless for comparative analysis? Table 1 about here Our theory holds that self-expression values should be strongly correlated with indicators of economic modernization. As Table 1 demonstrates, self-expression values do indeed show strong correlations with many standard indicators of economic modernization. Although measured at different levels and by different methods, we find remarkably strong linkages between individual-level values and the societies’ economic characteristics. Across all available societies, the average correlation between self- expression values and the ten economic modernization indicators is .77. 15 Now let us compare the strength of the correlations obtained from high-income societies, with those obtained from all available societies. Here, two effects work against each other: (a) the presumed loss of data quality that comes from including lower-income societies, which would be expected to weaken the correlations; and (b) the increased analytical leverage that comes from including the full range of societies, which should strengthen the correlations. Which effect is stronger? The results are unequivocal. Among high-income societies the average correlation between self-expression values and ten widely-used economic development indicators is . 57, while across all available societies the average correlation is .77. The data from all available societies explains almost twice as much variance as from the data from high- income societies only. Moreover, the correlations based on all available societies show much smaller standard deviations than do the correlations based on high-income societies — indicating that including the lower-income societies produces more coherent results. Our theory also implies that we should find strong linkages between self- expression values, and the emergence of civil society and the flourishing of democratic institutions. As Table 2 demonstrates, societal-level self-expression values are indeed closely correlated with a wide range of such indicators, including a Global Civil Society index; and World Bank indices of Government Effectiveness and of Non-corrupt and Lawful Governance. They are also correlated with the UNDP Gender Empowerment Measure, and an index of effective democracy.16

15 Since these values are correlated with economic indicators, one possibility would be to use the indicators as proxies, without measuring the values themselves. This ignores the fact that democracy does not result from being rich per se; it reflects sociocultural changes that tend to go with economic development but not in a 1:1 relationship. Accurate analysis requires direct measurement of these factors. 16 For a discussion of this index and how it is constructed, see Inglehart and Welzel, 2005: pp. 150-157. Perspectives on Politics (forthcoming, March, 2010) 17

Table 1. Correlations between Self-Expression Values and Key Indicators of a Society’s Economic Development

INDICATORS: HIGH-INCOME ALL AVAILABLE SOCIETIES ONLYa) SOCIETIESb) GDP/capita 2002 in PPP +.43* +.81*** (World Bank) (29) (86) Percent workforce in service sector, +.47* +.72*** 1990 (World Bank) (29) (86) Human Development Index 2000 +.75*** +.75*** (UNDP) (29) (77) Index of Power Resources 1993 +.73*** +.80*** (Vanhanen) (29) (88) Social Development Index 2005 +.71*** +.79*** (World Bank) (21) (79) Index of Knowledge Society 2005 +.65** +.80*** (UN) (22) (39) Social Accountability Index 2005 +.64** +.78*** (World Bank) (21) (79) Global Creativity Index 2000 +.57** +.75*** (Florida) (24) (45) Social Cohesion Index 2005 +.54** +.77*** (World Bank) (21) (79) Internet Use 2003 +.25 +.75*** (World Bank) (23) (65) AVERAGE +.57 +.77 (30) (72) (SD: .16) (SD: .06) a) Per capita GDP in 2002 from $13,500 to $65,000 at PPP. b) Per capita GDP in 2002 from $500 to $65,000 at PPP. * significant at .05 ** significant at .01 *** significant at .001 Perspectives on Politics (forthcoming, March, 2010) 18

Table 2. Correlations between Self-Expression Values and Key Indicators of a Society’s Socio-political Development

INDICATORS: HIGH-INCOME ALL AVAILABLE SOCIETIES ONLYa) SOCIETIESb) Non-corrupt and Lawful Governance +.64** +.82*** 2000-6 (World Bank) (29) (91) Government Effectiveness index 2000-6 +.60** +.81*** (World Bank) (29) (91) Human Rights Index 2000-3 (Cingranelli +.57** +.75*** & Richards) (25) (73) Civil Rights and Political Liberties 2000-4 +.54** +.70*** (Freedom House) (21) (91) Regulatory Quality Index 2000-6 +.53** +.75*** (World Bank) (29) (91) Effective Democracy 2000-6 +.81*** +.85*** (Inglehart & Welzel) (29) (90) Voice and Accountability Index 2000-6 +.79*** +.79*** (World Bank) (29) (91) Global Civil Society Index 2000 +.73** +.84*** (Anheier et al.) (18) (33) Summary Democracy Index 2000-4 +.69*** +.80*** (Welzel) (25) (71) Gender Empowerment Measure 2007 +.68*** +.75*** (UNDP) (28) (68) AVERAGE +.66 +.79 (26) (SD: .10) (79) (SD: .04)

a) Per capita GDP in 2002 from $13,500 to $65,000 at PPP. b) Per capita GDP in 2002 from $500 to $65,000 at PPP. * significant at .05 ** significant at .01 *** significant at .001

Table 2 about here Table 2 also shows another test of the data from low-income societies. If the presumably lower quality of these data outweighed the analytical leverage gained from their inclusion, including them should weaken their correlations with relevant societal phenomena. As comparing the two columns in Table 2 indicates, the correlations obtained from analyzing all available societies are consistently stronger than those obtained by analyzing only the data from high-income countries. The gains obtained by increasing the range of variation, more than compensate for the loss of quality. Space constraints do not permit us to analyze all twenty of the potential causal linkages suggested by these correlations. But for illustrative purposes, we will summarize some findings concerning one such linkage—that between Survival/Self- expression values and effective democracy. Perspectives on Politics (forthcoming, March, 2010) 19

Analyzing the emergence of democracy Analysis of the interplay between politics, economics and culture requires a different approach from the standard pooled time series method. This type of modeling is effective with processes in which an increase in variable X is regularly followed by an increase in variable Y after a time lag. But the linkages between economic growth, cultural change and the emergence of democratic institutions are characterized by threshold effects and blocking factors that do not follow this pattern. Economic development may bring a gradual build-up of cultural changes that reach a potentially significant threshold, but the break-through to democracy may be delayed by societal- level blocking factors until some triggering factor— such as the end of the Cold War— allows changes to occur. The standard pooled time series model does not capture such processes. Though economic growth may be the root cause of democratization, democracy does not usually emerge immediately after a surge of economic growth. On the contrary, high rates of growth can help to legitimate authoritarian regimes, and transitions to democracy may be triggered by recent economic decline. Nevertheless, economic development tends to bring long-term social and cultural changes that eventually tend to bring democracy—producing a strong correlation between the two. Modernization favors democracy because it enhances ordinary people’s abilities and motivation to demand democracy, exerting increasingly effective pressure on elites. Mass attitudes—particularly self-expression values—constitute a mediating variable in the causal path from economic development to democracy. Extensive analyses indicate that, while economic development has a strong impact on self-expression values, its impact on democracy is almost entirely transmitted through its tendency to bring increasing emphasis on self-expression values (Inglehart & Welzel 2005:181-3; Welzel 2007:409). Self-expression values are not, as sometimes claimed, “endogenous” to democratic institutions. (Figure 8 about here) Self-expression values have a strong impact on changes in levels of democracy— even when one controls for the possibility that these values are shaped by previous levels of democracy. Figure 8 demonstrates this point. At first glance, it looks like a cross- sectional analysis, but the dependent variable is change in democracy. The vertical axis shows the change in levels of democracy that occurred from 1984-1988 (before the latest wave of democratization) to 2000-2004 (after this wave).17 The horizontal axis shows each nation’s level of self-expression values in 1990 (the Figure 8. Level of Self-Expression Values and the Direction and Magnitude of Change in Levels of Democracy (controlling for starting levels of democracy with both variables)

17 For stable estimates, we use five-year periods before and after the wave of democratization. In both cases,, the level of democracy reflects the average of three indices of democracy: the Polity autocracy-democracy scores, the Freedom House civil liberties and political rights scores, and the Cingranelli/Richards integrity rights and empowerment rights. All indices are recoded into a range from 0 (the least democratic) to 100 (the most democratic). The change score is calculated by subtracting the level of democracy in 1984-88 from the level in 2000-04. The sign of the shift score indicates the direction of change (negative for movement away from democracy and positive for movement toward democracy). The magnitude indicates the amount of change. Perspectives on Politics (forthcoming, March, 2010) 20

55

50

45 Czech R. Slovakia 40

4 Slovenia 0 ) - 35 Estonia 8 0

8 Hungary 0 - 4 0 30 Latvia 8 2

Chile 9 1 o 25 t Taiwan Poland

n Croatia i Bulgaria 8 20 y 8 Romania - c 4 a 15 S. Africa S. Korea Switzld. r 8 c

9 Norway o

1 10 NL

U.S.A. Sweden m Ireland NZ Denmark e m 5 d Ghana Iceland o Belgium Germany r y Portugal Italy f G.B. b

0 Georgia Mexico y

d Canada c e -5 Philipp. El Salv.

a n Russia i r Bangladesh Japan

a Armenia c l -10 Peru Brazil p o Indonesia Israel x

e Dom. R. m -15 Argentina

n India e u

D -20 Nigeria

Tanzania s

l Turkey n i a

-25 u

e Algeria

d Azerb. i g

s -30 Uganda Belarus n Jordan e Venez. r a (

h -35 C -40 China Zimbabwe -45 y = 203.88x + 0.5558 2 -50 Pakistan R = 0.5174

-55 -0.20 -0.16 -0.12 -0.08 -0.04 0.00 0.04 0.08 0.12 0.16 0.20 Self-Expression Values in about 1990 (residuals unexplained by democracy in 1984-88) Perspectives on Politics (forthcoming, March, 2010) 21 midpoint of this wave) controlling for its level of democracy in 1984-1988. The countries that rank highest on this axis are not those that show the highest levels of self- expression values-- they are the ones with the highest level of self-expression values controlling for previous levels of democracy (which also controls for any variables that shape previous levels of democracy).18 Thus, this figure analyzes the impact of self- expression values on change in levels of democracy from the mid-1980s to the mid- 1990s, controlling for everything that has shaped democracy up to this point. One could interpret scores on the horizontal axis as reflecting unmet mass demand for democracy, which created a political tension that was released when the blocking factors disappeared around 1990. As the data demonstrate, the countries that had the highest unmet mass demand for democracy, were the ones that showed the largest subsequent movement toward democracy. Self-expression values exert pressure for changes in levels of democracy. These values emerge through slow but continuous processes, while democracy often emerges suddenly after long periods of institutional stagnation. Consequently, it is the level of self-expression values at the time of the break-through, not recent changes in these levels, that determines the magnitude of subsequent changes toward democracy.19 The analysis shown in Figure 8 is not the usual way to analyze change, but it is a much more appropriate way to analyze processes involving thresholds and blocking factors, as is true of the relationship between individual-level cultural change and societal-level democratization. The results indicate that a society’s level of self-expression values in 1990 accounts for over half of the change in levels of democracy from the mid-1980s to the mid-1990s The model used by Acemoglu and Robinson (2006) treats mass desire for democracy as a constant that cannot explain why democracy emerges.20 But as our theory implies-- and data from many countries confirms-- emphasize on self-expression values has grown in recent decades, increasing the strength of mass demands for democracy. Around 1990, changes on the international scene opened the way for dozens

18 The countries with the highest absolute levels of Self-expression values were established democracies such as The Netherlands, U.S., Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and Sweden. These countries had high levels of Self-expression values in 1990 but they also had high levels of democracy in 1990—indeed, they were near or at the maximum possible score, and could not rise any higher. Accordingly, they show little or no change (falling near the zero point on the vertical axis). Countries such as the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Slovenia, Estonia and Hungary had relatively high levels of Self-expression values but low levels of democracy, showed the greatest amount of change toward higher levels of democracy. Thus, this figure depicts the impact of the tension between unmet demands for democracy, on subsequent changes toward democracy. 19 Moreover, these values do not result from prior experience under democracy, for which this analysis controls. 20 Their model also leaves an unexplained elephant in the room. At the start of the 20th century, there were only a handful of democracies in the world; by the end of the century there were scores of democracies. If economic development didn’t produce this change, what did? Their model indicates that certain countries have always had the lead in both economic development and democracy, but doesn’t explain what drove the immense increase in democracy. As we argue, the root cause was economic and social modernization, which brought changes in values and social structure that made democracy increasingly likely. Perspectives on Politics (forthcoming, March, 2010) 22 of countries to democratize.21 The extent to which given countries then moved toward higher levels of democracy, reflects the strength of the unmet demand for democracy in these societies when this window of opportunity opened. Acemoglu and Robinson’s game theoretic model of how democracy emerges is powerful and parsimonious and may account for earlier waves of democratization, but it does not seem to explain this most recent wave. They (together with Boix, Weingast and other influential analysts) argue that rising capital mobility makes elites less fearful of economic redistribution and therefore more willing to grant democracy. We believe this is part of the story. But this top-down account underestimates the extent to which modernization also makes the masses increasingly adept at organizing to make effective demands for liberalization—and increasingly motivated to do so. Empirical evidence indicates that when socioeconomic development reaches a threshold at which a large share of the country’s population has grown up taking survival for granted, there is a change in the prevailing motivations for democracy. The most recent wave of democratization does not seem to have been motivated mainly by a desire for greater income equality, as their model holds; it was driven by the fact that a large share of the population gave high priority to freedom itself. This is particularly true of the democratization movements in communist countries, which were acting against regimes that already provided relatively high levels of economic equality-- and installed regimes that provided less economic equality but higher levels of freedom. CONCLUSION Our revised version of modernization theory implies that economic development tends to bring enduring changes in a society’s values that, at high levels of development, make the emergence and survival of effective democracy increasingly likely. Evidence from scores of societies indicates that modernization-linked values and attitudes show sufficient stability over time to be treated as attributes of given societies. Moreover, the self-expression values syndrome shows remarkably strong linkages with a wide range of societal phenomena such as civil society, gender equality and democratization. These correlations suggest that causal linkages are involved. Social scientists have long suspected that people’s beliefs and values play an important role in how societies function, but until recently empirical measures of these orientations were not available from enough countries for statistically-significant analysis at the societal level. When one does so, the linkages between subjective orientations and objective societal phenomena show impressive strength. We have presented evidence that certain modernization-linked mass attitudes are stable attributes of given societies and powerful predictors of effective democracy. While we do not attempt to test the other causal linkages suggested here, other research supports the claim that changing mass attitudes impact on objective gender equality (Inglehart and Norris, 2003), the democratic peace (Inglehart and Welzel, 2009) economic growth rates (Barro and McCleary, 2003) and intergroup cooperation (Zak and Knack, 2001). Much work remains to be done spelling out the ways that these dynamics play out in specific places and times. And we fully expect that scholars will continue to disagree about the relative weight to attach to the attitudinal variables that loom so large in our own theory of

21 The end of the Cold War removed the most important blocking factor, but this was supplemented by such conditions as the attainment of high levels of development in Taiwan and South Korea. Perspectives on Politics (forthcoming, March, 2010) 23

modernization. But we hope to have shown here that the kind of skepticism about mass attitudes shared by many political scientists is unwarranted, and that there is every reason for these attitudes to be considered in theories of democratization and social change.

REFERENCES Acemoglu, Daron and James A. Robinson. 2000. Why did the West extend the franchise? Growth, inequality and democracy in historical perspective. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 115: 1167-99. Acemoglu, Daron and James A. Robinson. 2001. A theory of political transitions. American Economic Review. 91:938-63. Acemoglu, Daron and James A. Robinson. 2006. Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy. New York: Cambridge University Press. Barro, Robert J. and Rachel M. McCleary . 2003. Religion and Economic Growth across Countries. American Sociological Review, Vol. 68, No. 5, pp. 760-781. Boix, Carles. 2003. Democracy and Redistribution. New York: Cambridge University Press. Deutsch, Karl W. 1964. Social mobilization and political development. American Political Science Review 55, 3 (September):493-514. Haerpfer, Christian, Patrick Bernhagen, Ronald Inglehart and Christian Welzel, (eds.) Democracy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. Inglehart, Ronald and Pippa Norris. 2003. Rising Tide: Gender Equality and Cultural Change Around the World (New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Inglehart, Ronald and Christian Welzel. 2005. Modernization, Cultural Change and Democracy. New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Inglehart, Ronald and Christian Welzel. 2009. “How Development Leads to Democracy: What We Know About Modernization.” Foreign Affairs March/April: 33-48. Inglehart, Ronald and Wayne Baker. 2000. Modernization, Cultural Change and the Persistence of Traditional Values. American Sociological Review. (February): 19-51. Inglehart, Ronald. 1997. Modernization and Postmodernization: Cultural, Economic and Political Change in 43 Societies. Princeton: Princeton University Press. Lipset, Seymour M. 1959. “Some Social Requisites of Democracy: Economic Development and Political Legitimacy.” American Political Science Review 53 (March): 69-105. Moore, Barrington. 1966. The Social Origins of Democracy and Dictatorship: Lord and Peasant in the Making of the Modern World. Boston: Beacon Press. Norris, Pippa. 2009. “The Globalization of Comparative Public Opinion Research.” In Todd Landman and Neil Robinson (eds.) The Sage Handbook of Comparative Politics. Sage Publications, London and Los Angeles. Norris, Pippa and Ronald Inglehart. 2004. Sacred and Secular: Religion and Politics Worldwide. New York: Cambridge University Press. Przeworski, Adam, M. Alvarez, JA Cheibub and F Limongi. 2000. Democracy and Development: Political Institutions and Well-being in the World, 1950-1990. New York: Cambridge University Press. Robinson, James A. 2006. Economic Development and Democracy. Annual Review of Political Science 9:503-527. Perspectives on Politics (forthcoming, March, 2010) 24

Robinson, W.S. (1950). Ecological Correlations and the Behavior of Individuals. American Sociological Review 15: 351-357. Schwartz, Shalom H. (2003). “Mapping and Interpreting Cultural Differences around the World.” in Henk Vinken, Joseph Soeters, and Peter Ester (eds.), Comparing Cultures, Dimensions of Culture in a Comparative Perspective. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill. Schwartz, Shalom H. (2006). A Theory of Cultural Value Orientations: Explication and Applications. Comparative Sociology 5: 137-182. Seligson, Mitchell. 2002. The Renaissance of Political Culture or the Renaissance of the Ecological Fallacy? Comparative Politics 34:273-92. Vanhanen, Tatu (ed.). 1997. Prospects of Democracy: A Study of 172 Countries. London: Routledge. Welzel, Christian, Ronald Inglehart and Hans-Dieter Klingemann (2003). “The Theory of Human Development: A Cross-Cultural Analysis.” European Journal of Political Research 42 (2): 341-380. Welzel, Christian. 2007. “Are Levels of Democracy Influenced by Mass Attitudes?” International Political Science Review 28(4):397-424. Welzel, Christian and Ronald Inglehart (2008). “Democratization as Human Empowerment.” Journal of Democracy 19(1): 126-140. Welzel, Christian and Ronald Inglehart (2009). “Political Culture, Mass Beliefs and Value Change.” In Christian Haerpfer et al. (eds.) Democratization. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp. 126-144. Zak, Paul J. and Stephen Knack. 2001. “Trust and Growth.” The Economic Journal 111: 295- 321.