1. Population we serve: Census 2006 showed Auckland City’s population to be 428,310 people, a growth of 10.2% from Census 2001. The growth is expected to slow down to 8.4% through to year 2011 with a population estimated number of 464,296 in 2011.

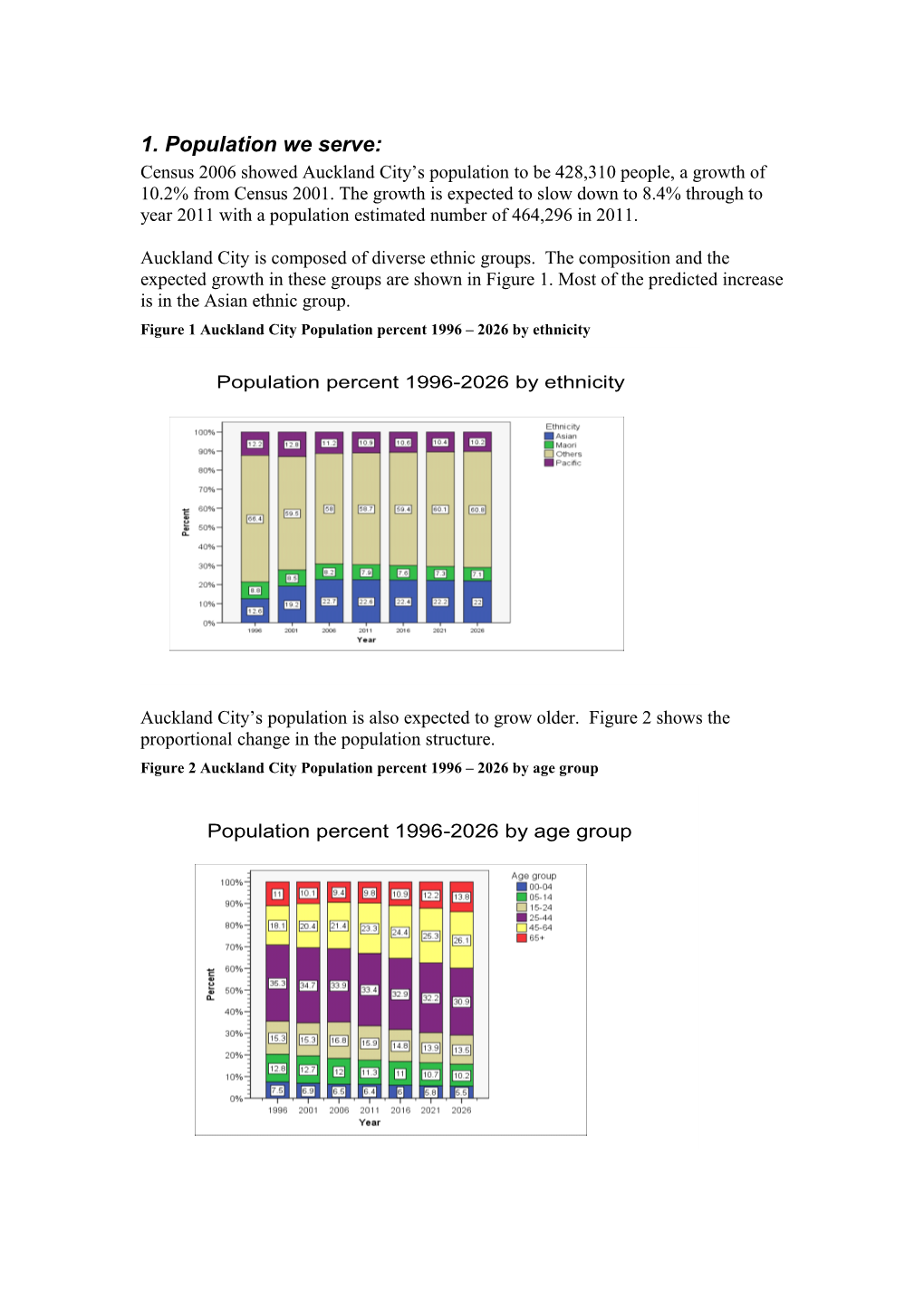

Auckland City is composed of diverse ethnic groups. The composition and the expected growth in these groups are shown in Figure 1. Most of the predicted increase is in the Asian ethnic group. Figure 1 Auckland City Population percent 1996 – 2026 by ethnicity

Population percent 1996-2026 by ethnicity

Auckland City’s population is also expected to grow older. Figure 2 shows the proportional change in the population structure. Figure 2 Auckland City Population percent 1996 – 2026 by age group

Population percent 1996-2026 by age group Hauraki Gulf

The distribution of Auckland City’s population by ward, ethnicity and NZDep06 is shown in Table 1 and Figure 3. Out of the 7 wards, three were highly populated. These are Avondale Roskill, - 23% of Auckland City population, and Hobson and Tamaki-Maungakiekie at 20% of the population each. The least populated ward is Hauraki Gulf Islands with only 2% of the Auckland population. More than half of the population living in Tamaki were living in the most deprived areas, compared to the total for Auckland of 31% living in the most deprived areas. Table 1 Auckland City population distribution by ward, ethnicity and NZDep06, year 2006 d r a w

t a h t

n i

. p n e o c s d p i i i

n r t n f e t r i a e a % a i d s o l i c

h d a t o t d u s d a r r n s p P A M M I O a a

o o W P W % % % % % M % Avondale Roskill 96,913 23% 20% 29% 33% 46% 17% 37,165 38% Hobson 84,240 20% 9% 3% 32% 9% 23% 19,196 23% Western Bays 41,286 10% 9% 8% 3% 3% 12% 4,244 10% Eastern Bays 48,682 11% 8% 3% 9% 3% 15% 4,050 8% Tamaki-Maungakiekie 86,688 20% 39% 46% 20% 26% 13% 48,127 56% Eden-Albert 61,374 14% 12% 10% 2% 13% 18% 16,864 27% Hauraki Gulf Islands 9,148 2% 4% 1% 0% 0% 3% 4,724 52% Total Auckland city 428,331 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 100% 134,370 31% Total Auckland city 428,331 29,856 50,196 56,374 29,892 262,013

Figure 3 Auckland City map by Mesh Block, NZDep06 and Wards

Western bays

Eastern bays Hobson

Eden-Albert

Avondale-Roskill

Tamaki-Maungakiekie 2. Who provides the service?

2.1 Medical practitioners

Table 2 shows the number of active medical practitioners by primary employment by DHB using results from the Medical Council Work force Survey (MCWS), 2003. An active medical practitioner is a person who holds an annual practising certificate and works four or more hours per week in NZ in medical or related work. Table 2: Number of active medical practitioners by primary employment and DHB (MCWS, 2003)

House DHB GP MOSS Registrar Specialist Other Primary Care Not stated Total Officer Auckland 400 178 39 355 670 77 51 15 1,785 CM 252 69 22 141 206 18 12 6 726

313 38 26 64 201 19 15 * 679 Waitemata

116 21 14 20 62 * * * 239 Northland NZ 3,006 842 303 1,319 2873 244 138 65 8,790

Table 3 shows the percentage of medical practitioners by ethnic group for NZ. Table 3: Percentage of medical practitioners in NZ by ethnic group (MCWS, 2003)

Ethnic group Percentage Maori 2.7

Pacific 1.1

Chinese 5.4

Indian 4.9

Other 9.1

NZ European 60.0

Other European 14.6

Not stated 2.1 Total 100

2.2 General practitioners

General practitioners (GPs) make up the largest group of medical practitioners accounting for 34.2% of the medical workforce responding to the workforce survey. There were 2,958 active medical practitioners working mainly as GPs in NZ in 2005 (2,851 FTEs). Auckland DHB has a high rate of GP FTEs (83 per 100,000) compared to the national rate (70 per 100,000). 2.3 Specialists

A specialist is a medical practitioner who is generally understood to require membership of a relevant specialist college, although self-reporting leads to broader usage in survey results. This section only includes medical practitioners who practise as specialists at their main employment location, and excludes those who practise as specialists in their second or third employment location. Table 4: Specialists by work type and DHB (Medical Workforce Survey, 2003)

Specialist Work Type Northland Waitemata Auckland CMDHB Total

Not Answered 0 * 9 * 42 Other * * 4 * 19 Accident and medical practice 0 0 * 0 * Anaesthesia 8 25 83 34 373 Basic medical science 0 0 4 0 8 Breast medicine 0 * 5 0 6 Cardiothoracic surgery 0 0 8 0 18 Dermatology 0 5 12 * 43 Diagnostic and interventional radiology 6 27 48 17 208 Emergency medicine * 4 6 10 41 General surgery 5 10 22 5 142 Intensive care medicine * * 5 * 18 Internal medicine 8 32 125 40 504 Medical administration 0 0 4 0 12 Musculoskeletal medicine 0 * * 0 9 Neurosurgery 0 0 5 0 11 Obstetrics and gynaecology 5 18 42 9 170 Occupational medicine 0 4 10 * 36 Ophthalmology * * 20 * 85 Orthopaedic surgery 5 4 29 17 157 Otolaryngology head and neck surgery * 5 15 * 63 Paediatric surgery 0 0 5 0 9 Paediatrics 7 * 47 12 157 Palliative medicine 0 * 5 * 19 Pathology * * 36 9 146 Plastic and reconstructive surgery 0 * 4 13 37 Primary Care 0 * 4 * 12 Psychiatry 4 38 44 14 288 Public health medicine * * 24 5 102 Radiation oncology 0 0 9 0 25 Rehabilitation medicine 0 0 * 0 7 Sexual health medicine 0 0 * 0 7 Sports medicine 0 0 * * 8 Surgery: Other 0 * 12 * 34 Surgery: Urology * * 10 0 39 Vascular surgery 0 0 4 * 13 Total number of specialists 62 201 670 206 2873

Specialists made up the second largest group of medical practitioners reported in the annual workforce survey, accounting for 32.7% of the medical workforce responding to the workforce survey. There were 2,873 active medical practitioners working as specialists in NZ in 2003. Auckland has the highest rate of specialists (174.6 per 100,000) compared to the national rate (72.9 per 100,000). The high rate in the Auckland area could be due to the fact that Auckland DHB provides many national and regional highly specialised services. 2.4 Registered nurses and midwives

This data was obtained from the 2004 nursing and midwifery workforce survey (NMWS). A registered nurse is defined by the Nurses Act 1977 as a nurse whose name is recorded on the Register of Nurses. A midwife may be a registered general and obstetric comprehensive nurse who has undertaken further education to gain midwifery qualifications, or a graduate of a direct-entry midwifery course. Direct- entry midwives may have graduated in another country before 1995 and subsequently gained NZ registration.

In 2004 there were 34,660 active registered nurses and midwives working in nursing and midwifery in NZ. This included 196 midwives who gained a direct-entry midwifery qualification. Auckland has a low rate of active registered nurses and midwives working in nursing and midwifery (772 per 100,000) compared to the national rate (854 per 100,000).

2.5 Enrolled nurses

An enrolled nurse is defined in the Nurses Act 1997 as a nurse whose name is recorded on the Roll of Nurses. Legislation restricts the scope of practice for enrolled nurses requiring them to practise under the supervision of a registered nurse or medical practitioner. Up until recently there had been no enrolled nursing education programmes offered in NZ since 1993.

In 2004 there were 3824 active enrolled nurses in NZ (94.1% female, 3.1% male and 2.7% unknown). The Auckland region has a low rate of active enrolled nurses (55.9 per 100,000) compared to the national rate (94.2 per 100,000).

2.6 Midwives

Nurses in the workforce are classified as midwives because of their qualifications. They need not be working as a midwife to be included here. Nurses with midwifery qualifications were also included in Section 6.4 ‘registered nurses and midwives’, but the data for them is analysed further in this section.

There were 3,780 nurses who held a midwifery qualification in 2004 and met the criteria for an active nurse or midwife (97.4% female, 0.3% male and 2.3% unknown). Included in the 3,780 were 196 midwives who gained their midwifery qualifications from a direct-entry course. The Auckland region has a lower rate of active nurses with midwifery qualifications working in nursing and midwifery (88.6 per 100,000) than the national rate (93.1 per 100,000). An additional 19 active nurses with midwifery qualifications would be needed to bring Auckland up to the national average.

2.7 Dentists The data presented in this section on the active dentist workforce in NZ was obtained from the Dental Council of New Zealand annual workforce survey 2003 and the Dental Register. The overall response rate for the survey was 95.2 percent. An active dentist is defined as a person who is on the Dental Register and holds an annual practising certificate (APC) in NZ.

In 2003 a total of 1,662 dentists were on the Dental Register and had a current APC, and the survey response rate was 95.2% i.e. 1582 dentists responded. Auckland DHB had a much higher rate of active dentists (111.1 per 100,000) than the national rate (54.8 per 100,000).

2.8 Primary Care Organisations:

Table 5 shows that around 78% of the Auckland City population are currently enrolled with one of the five Auckland City PHOs and 22% of our population are enrolled with a PHO outside of Auckland City. Seventy percent of our enrolled population were enrolled with ProCare PHO. Most Maori (54%) were enrolled with ProCare and 26% with Tamaki Healthcare Trust. Most Pacific people (46%) were enrolled with ProCare, while 21% were enrolled with AuckPAC Health Trust and 18% with Tamaki Healthcare Trust. Table 5: Number of working doctors in Auckland City primary care organisations by enrolled populations and ethnicity.

Ethnicity

N Drs (Full PHO name Maori % Maori Pacific % Pacific Other % Other Total Enrolled % Total Time)* Auckland PHO Limited 2,425 0 5,089 0 35,658 0 43,172 0 41 AuckPAC Health Trust Board 2,378 10% 12,716 21% 22,079 6% 37,173 9% 20 Procare Network Auckland Limited 13,173 54% 28,395 46% 261,167 76% 302,735 70% 272 Tongan Health Society Incorporated 18 0% 4,816 8% 121 0% 4,955 1% 5 Tamaki Healthcare Charitable Trust 6,218 26% 10,915 18% 26,447 8% 43,580 10% 55

Total enrolled population, Auckland DHB 24,212 100% 61,931 100% 345,472 100% 431,615 100% 393 Total Aucklanders enrolled with Auckland DHB PHO 19,021 79% 43,652 70% 273,391 79% 336,064 78%

Total non Aucklanders enrolled with Auckland DHB PHO 5,191 21% 18,279 30% 72,081 21% 95,551 22%

The distribution of GPs and the rate per 1,000 by Ward is shown in Table 6 and Figure 4. The highly populated areas with the highest deprivation had the least number of doctors per 1,000 populations. Hauraki Gulf

Table 6: Auckland City populations by wards, NZDep06, number of doctors and rate per 1,000 populations d r a w

t a h t

n i r

0 . D 0

p f n 0 e o o 1 p d

i

r t r e t e a % e d s l

b p t o d u d

r r s m p e M a a t

o u o a W P W M % N r Avondale Roskill 96,913 23% 37,165 38% 69 0.7 Hobson 84,240 20% 19,196 23% 102 1.2 Western Bays 41,286 10% 4,244 10% 57 1.4 Eastern Bays 48,682 11% 4,050 8% 50 1.0 Tamaki-Maungakiekie 86,688 20% 48,127 56% 60 0.7 Eden-Albert 61,374 14% 16,864 27% 52 0.8 Hauraki Gulf Islands 9,148 2% 4,724 52% 10 1.1 Total Auckland city 428,331 100% 134,370 31% 400 0.9

Figure 4 Auckland City Practices with free under sixes by CAU and NZDep06 (Y=Yes, N=No, U=unknown)

U U Y U U Y U U U U N UU U U U U U Western bays N U N N U U U U U N N N Y Y U Y U N U Y Eastern bays U Y Hobson U U N N U U Y Y U U U Y Y U U U U Eden-Albert UU U U Y U N N U U U U U U Y N Y U U Y U U U Avondale-RoskillY N N N Y Avondale-Roskill Y N U U N U U U Y Y U U Y U U U Y U Tamaki-MaungakiekieU N Y Y U N U U N Y N Y N U Y N

U

N

U Hauraki Gulf

Figure 5 Auckland City practices by Wards for VLCA by CAU and NZDep06 (Y=Yes, N=No, U=unknown)

U U U N U N U U U Y UU U U U WesternU bays UU U Y U U U NY U Y U N U Y U Eastern bays N NU Hobson U U Y Y U U N N N U U U N U U U Eden-Albert U U UU U U N Y U U U U Y U N U U U N U N U U Y Avondale-RoskillN N Avondale-Roskill Y N Y Y Y U Y U U U U N U U N U U U N U N Y Tamaki-MaungakiekieU U N U U Y N Y N N Y Y U N Y

U

Y

U

Pharmacies

Table 7 and Figure 6 show the distribution of the 119 pharmacies in Auckland City. Table 7 Distribution of Auckland city pharmacies by wards populations, number of scripts and reimbursement value, year 2007. d l n t a a p l t i k o r c c T

u s l

m r A a

t e o r o p m f

s T o

e e t r d f i f r u s

o l c a o n a a n s o v C % t W o i

m t t t t p r s r i a r n n n e r a l e e e e p c h u

p S p

p m m m s

r t f f e e e n o e p o s s s o o p i

i p r r r r r r t d u u u c e s e a r l t b b b s b b a

u p d f i m m m r m m p i i i r W o a

u e e e u o c W P % N % S R R R N Avondale Roskill 96,913 23% 743,772 25% 8 $20,411,944 24% $ 27 22 Eastern Bays 48,682 11% 351,012 12% 7 $10,003,739 12% $ 28 12 Eden-Albert 61,374 14% 338,514 12% 6 $10,869,628 13% $ 32 14 Hauraki Gulf Islands 9,148 2% 47,186 2% 5 $1,715,958 2% $ 36 2 Hobson 84,240 20% 472,520 16% 6 $14,512,450 17% $ 31 33 Tamaki-Maungakiekie 86,688 20% 699,155 24% 8 $19,131,793 22% $ 27 24 Western Bays 41,286 10% 270,833 9% 7 $8,540,448 10% $ 32 12 Total Auckland city 428,331 100% 2,922,992 100% 7 $85,185,960 100% $ 29 119 Hauraki Gulf

Figure 6 Auckland City Pharmacy distributions by wards and CAU.

Western bays

Eastern bays Hobson

Eden-Albert

Avondale-Roskill

Tamaki-Maungakiekie Hauraki Gulf

Laboratory services

There are 32 laboratory sample collection centres. Their distribution is shown in Table 8 and Figure 7.

Table 8 Auckland city populations with number of laboratory tests ordered and $ cost, year 2007. d n a l l k a t c o u T A

m m m n o o o r o r f o f s r

r d n r e n o a p o i l n

i s t t r t a s W o a t

c e s l s r o m e r e p u i l e

T l e T p a

p e

l f o p f n o

u s C o l r o C o p

t

i a f e r r t s d % v o p e e a e r

l t b b a e s d u m m f t i i r u m m p l s W o a a a

u l l u o a e W P % N % T V C C N Avondale Roskill 96,913 23% 574,899 22% 6 $2,829,608 22% $29 4 Eastern Bays 48,682 11% 382,984 15% 8 $1,915,209 15% $39 2 Eden-Albert 61,374 14% 313,334 12% 5 $1,611,802 12% $26 3 Hauraki Gulf Islands 9,148 2% 51,556 2% 6 $268,066 2% $29 2 Hobson 84,240 20% 495,058 19% 6 $2,594,102 20% $31 8 Tamaki-Maungakiekie 86,688 20% 532,385 21% 6 $2,646,118 20% $31 5 Western Bays 41,286 10% 244,860 9% 6 $1,262,555 10% $31 4 Total Auckland city 428,331 100% 2,595,076 100% 42 $13,127,460 100% $31 28

Figure 7 Auckland city collections centres by wards, year 2007.

Western bays

Eastern bays Hobson

Eden-Albert

Avondale-Roskill

Tamaki-Maungakiekie 3. How we use our health services This section presents data on the frequency of visits to the following health providers, obtained from the New Zealand Health Survey (NZHS) 2002/03: GPs, Maori and Pacific health providers, medical specialists, nurses, and public/private hospitals.

3.1 General practitioners

The percentage of people who had seen their GP was identified from the NZHS 2002/03 as those who stated they had seen a GP or their family doctor in the last 12 months. In total people living in Auckland DHB were slightly less likely to have seen their GP in the last 12 months than those in the whole of New Zealand (Table 9).

Table 9: Percentage of people who visited a GP in the past 12 months

DHB GP visit: age-standardised prevalence (%) Males Females Total M P A O T M P A O T M P A O T Auckland 68.9 70.8 58.4 78.3 73.7 83.9 81.2 68.4 87.7 83.4 77.0 76.5 63.8 83.1 78.8 Counties– 66.8 64.5 68.7 80.2 74.7 81.4 83.7 73.6 85.8 83.4 74.8 74.6 71.3 83.0 79.2 Manukau Waitemata 68.7 66.9 53.8 76.3 73.2 82.4 80.8 68.2 88.1 85.3 75.9 74.5 61.6 82.4 79.5 Northland 67.7 66.1 61.2 82.3 78.7 81.8 88.8 64.5 85.4 84.2 75.4 74.7 63.2 83.9 81.6 New Zealand 67.8 75.1 63.8 77.7 75.7 82.5 83.7 73.8 87.0 85.5 75.7 79.6 69.2 82.4 80.8

The percentage of people who visited a GP in the previous 12 months was similar for Auckland DHB (78.8%) and the rest of the Auckland region, but slightly less than Northland (81.6%), and nationally (80.8%). Females were significantly more likely to visit a GP (83.4%) than males (73.7%) in Auckland DHB, the other Auckland DHBs, and nationally.

Figure 8 shows that within Auckland DHB fewer Maori (77%), Pacific (76.5%) and Asians (63.8%) visited a GP than Others (83.1%). The difference between Asian and Others was significant. While a higher prevalence of females than males had visited a GP for all ethnic groups, this difference was only significant for European and others (females 87.7%, males 78.3%). Figure 8 Percentage of people who visited a GP in the previous 12 months in Auckland DHB by sex and ethnic group

Nationally, in both males and females, adults aged 65 years and over were significantly more likely than adults aged 15–24 years to have seen a GP in the last 12 months. Up to age 44 years, females were significantly more likely than males to have seen a GP in the last 12 months. In both males and females, there was no significant difference in the use of GP services between NZDep01 quintile 1 (least deprived) and quintile 5 (most deprived).

Using NatMedCa data, published year 2001/02 by the Ministry of Health, Table 10 presents the percentage distribution of visits, by age group and gender, as a ratio of the age and gender distribution of the population. The consultation rate is twice the average in the first five years of life. It also increases substantially above average in women from age 55 and in men from age 65.

Table 10: Ratio of visits to national population, by age and gender

ll ags 0-4 5-14 5-24 25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65-74 75+ Male 0.86 1.96 0.6 0.48 0.52 0.62 0.75 1.06 1.45 2 Female 1.14 1.92 0.6 0.85 0.95 0.91 1.07 1.33 1.73 2.29

Using the above table and assuming utilisation in Auckland City is similar to the national rate Table 11 shows the expected number of visits per age and gender groups, year 2006. The number of visits in year 2011 would be expected to be 465,477 visits per year. Table 11: Auckland City population, expected number of visits by gender and age group, year 2006

ll ags 0-4 05-14 5-24 25-34 35-44 45-54 55-64 65-74 75+ Male 180,290 27,910 15,846 16,963 19,328 20,888 20,228 19,313 14,660 14,980 Female 249,284 25,862 14,898 31,025 37,269 32,141 29,917 24,645 18,822 27,366 Total 429,574 53,773 30,744 47,988 56,597 53,029 50,145 43,958 33,482 42,346 3.1.1 Number of visits

Overall, the mean number of GP visits among adults who had seen a GP in the last 12 months was four visits (3.8–4.1). The mean number of visits to a GP was significantly higher in females (4.3 visits; 4.1–4.5) than in males (3.5 visits; 3.3–3.8).

In males, the mean number of GP visits was highest in Maori (4.2 visits; 3.7–4.8), followed by Pacific (4.1 visits; 3.3–5.0), Asian (3.8 visits; 2.4–5.2) and European/Other (3.4 visits; 3.2–3.6) ethnic groups. In females, the mean number of GP visits was highest in Maori (5.3 visits; 4.4–6.2), followed by Pacific (4.8 visits; 4.1–5.6), European/Other (4.2 visits; 4.0–4.4) and Asian (3.5 visits; 3.0–4.1) ethnic groups.

3.1.2 Seen more than one general practitioner

Overall, three out of 10 adults (31.4%; 30.1–32.7) who had seen a GP in the last 12 months reported seeing more than one GP. Females (36.1%; 34.4–37.8) were significantly more likely than males (28.1%; 26.0–30.3) to have seen more than one GP in the last 12 months. Maori males were most likely to have seen more than one GP in the last 12 months, followed by European/Other, Pacific and Asian males, although these differences were not significant. European/Other and Maori females were significantly more likely than Pacific and Asian females to have seen more than one GP.

3.2 Maori health providers

The percentage of Maori people who had attended a Maori health provider was identified from the NZHS 2002/03 as those who had seen a healthcare worker at a Maori health provider in the last 12 months. Results were presented for the Maori ethnic group only due to the small number of non-Maori using these services (Table 12). Table 12: Percentage of Maori people who saw a healthcare worker at a Maori health provider in the past 12 months (NZHS 2002/03)

DHB Maori health provider visit: age-standardised prevalence (%) Maori males Maori females Maori total Auckland 5.6 10.4 8.2 Counties–Manukau 13.0 20.2 16.9 Waitemata 5.2 8.6 7.0 Northland 14.6 20.3 17.7 New Zealand 10.9 16.1 13.7

Nationally, one in seven Maori adults (13.7%; 11.3–16.0) had seen a healthcare worker from a Maori health provider in the last 12 months. Doctors were the most common type of healthcare worker seen at a Maori health provider. 3.3 Pacific health providers

The percentage of Pacific people who had attended a Pacific health provider was identified from the NZHS 2002/03 as those who stated they had seen a healthcare worker at a Pacific health provider in the last 12 months. Results were presented for the Pacific ethnic group only due to the small number of non-Pacific using these services (Table 13). Table 13 Percentage of Pacific people who saw a healthcare worker at a Maori health provider in the past 12 months

DHB Pacific health provider visit: age-standardised prevalence (%) Pacific males Pacific females Pacific total Auckland 6.9 8.4 7.7 Counties–Manukau 13.7 12.2 12.9 Waitemata 6.4 8.2 7.3 Northland 18.0 15.8 16.9 New Zealand 9.1 9.6 9.4

3.4 Medical specialists

The percentage of people who had seen a medical specialist was identified from the NZHS 2002/03 as those who stated they had seen a medical specialist in the last 12 months. As shown in Table 14, in Auckland DHB, Maori, Pacific, and particularly Asian males and females were less likely to have seen a specialist in the last 12 months than their counterparts in the rest of the Auckland region. People of Other ethnic groups were more likely to have visited a specialist than people of other ethnicities across all DHBs. Table 14 Percentage of people who visited a medical specialist in past 12 months

DHB Specialist visit: age-standardised prevalence (%) Males Females Total M P A O T M P A O T M P A O T Auckland 16.9 16.5 13.5 31.0 25.9 29.5 17.8 16.8 35.9 30.3 23.8 17.2 15.3 33.5 28.2 Counties– 25.5 24.8 31.4 31.5 29.7 28.1 19.8 17.9 34.8 29.4 27.0 22.2 24.3 33.2 29.5 Manukau Waitemat 14.5 17.1 12.8 30.7 27.2 26.4 18.0 17.0 36.8 33.0 20.7 17.6 15.0 33.9 30.2 a Northland 24.5 27.9 42.7 28.9 28.1 27.7 22.0 24.8 34.4 32.5 26.2 25.7 31.9 31.7 30.4 New 22.9 20.5 18.3 29.8 28.0 27.3 20.1 20.4 35.1 32.6 25.3 20.2 19.4 32.5 30.4 Zealand

Table 14 shows that the percentage of people who visited a medical specialist in the previous 12 months was slightly low for Auckland DHB (28.2%) compared to other Northern Region DHBs and the whole of New Zealand. Except in Counties– Manukau DHB a greater percentage of females than males had visited a medical specialist, with this difference being significant in Auckland, Waitemata, and nationally (females 32.6%, males 28.0%). This may be due to a lower use of specialists in pregnancy-related care in Counties–Manukau. In Auckland DHB Other ethnic groups were more likely to visit a medical specialist (33.5%) than Maori (23.8%), Pacific (17.2%), and Asian (15.3%) groups. However, the only significant difference was between European/Others and Pacific/Maori/Asian ethnic groups. Females in all the ethnic groups tend to visit a medical specialist more than males. However, the difference was not significant.

3.5 Pharmacists

Most adults (85.4%; 83.9–86.9) had been to a pharmacy or chemist for a health product or health information or advice in the last 12 months. Females (90.5%; 89- 92) were significantly more likely than males (79.7%; 77–82.4) to have been to a pharmacy or chemist in the last 12 months. Asian males were significantly less likely than Pacific and European/ Other males to have been to a pharmacy or chemist in the last 12 months. European/Other females were more likely than females from other ethnic groups to have been to a pharmacy in the last 12 months, but this was statistically significant only with Asian females.

Among adults who had visited a pharmacy or chemist in the last 12 months, the overall mean number of visits was 6.7 visits (6.5–6.9). The mean number of visits to a pharmacy or chemist was significantly higher in females (7.7 visits; 7.4–8.0) than in males (5.3 visits; 5.0–5.5).

Table 7 shows the distribution of pharmaceuticals utilisation by wards for year 2007.

WHERE IS TABLE?

3.6 Nurses

The percentage of people who had seen a nurse was identified from the NZHS 2002/03 as those who stated they had seen a nurse at a GP’s practice or at home in the last 12 months (excluding midwives and nurses seen in hospital) is shown in Table 15. Table 15 Percentage of people who were seen by a nurse in the past 12 months

DHB Nurse visit: age-standardised prevalence (%) Males Females Total M P A O T M P A O T M P A O T Auckland 30.9 33.7 20.0 40.5 35.9 47.9 38.7 26.2 49.6 44.3 40.1 36.5 23.3 45.2 40.3 Counties– 31.8 19.2 15.8 37.4 31.3 49.9 34.3 28.0 50.9 45.3 41.8 27.2 22.3 44.3 38.6 Manukau Waitemata 30.1 37.1 15.6 41.1 37.8 49.7 35.3 27.0 49.4 46.4 40.4 36.1 21.7 45.4 42.2 Northland 33.1 22.3 10.5 39.9 37.8 50.6 34.3 26.6 52.4 51.4 42.7 26.8 20.3 46.2 44.8 New Zealand 33.9 27.0 22.2 38.5 36.6 49.2 36.2 29.8 49.9 48.0 42.1 31.9 26.3 44.4 42.5

The percentage of people seen by a nurse in Auckland DHB (40.3%) was lower than Waitemata, Northland and nationally (42.5%), although, Counties–Manukau DHB was the lowest (38.6%). The difference was not statistically significant (Table 13). Significantly more females (48.0%) than males (36.6%) were seen by a nurse, and males in Auckland DHB were the second least likely after Counties–Manukau to have been seen by a nurse, 35.9% and 31.3% respectively.

In Auckland DHB Others (45.2%) and Maori (40.1%) were more likely to have seen a nurse in the previous 12 months than Pacific (36.5%) or Asian people (23.3%). Female prevalence (44.3%) was higher than male prevalence (35.9%) in all ethnic groups and was significantly higher for Others (49.6%) females.

3.7 Practice nurses

Nationally, about one in four adults (27.4%; 26.2–28.5) had seen a practice nurse alone as part of a consultation with the GP in the last 12 months. Females (29.5%; 27.9–31.1) were significantly more likely than males (23.8%; 22.1–25.5) to have seen a practice nurse as part of a GP consultation. The overall mean number of visits to a nurse in the last 12 months as part of a GP consultation was 2.7 visits (2.5–2.9). There was no significant difference in the mean number of nurse visits between males (2.6 visits; 2.3–3.0) and females (2.7 visits; 2.4–3.1).

Overall, one in six adults (16.4%; 15.3–17.4) had seen a nurse in the last 12 months without seeing a GP at the same time. Females (18.8%; 17.4–20.2) were significantly more likely than males (12.0%; 10.7–13.3) to have seen a nurse without seeing a GP. Overall, the mean number of visits to a nurse in the last 12 months without seeing a GP was 2.8 visits (2.6–3.1). There was no significant difference in the mean number of nurse visits between males (2.9 visits; 2.5–3.3) and females (2.6 visits; 2.4–2.9).

3.8 Other nurses

Overall, one in nine adults (11.2%; 10.1–12.2) had seen another type of nurse (ie, not a practice nurse, midwife or nurse in hospital) in the last 12 months. Females (12.8%; 11.5–14.2) were significantly more likely than males (9.4%; 8.0–10.8) to have seen other types of nurse. Among adults who had seen other nurses, the common types of nurse were: Plunket nurse (females 22.5%; 18.6–26.3) district nurse (16.5%; 13.8–19.2) occupational health nurse (15.4%; 12.8–18.1) dental nurse or therapist (9.9%; 7.2–12.6) public health nurse (8.2%; 6.1–10.3) diabetes nurse (7.3%; 5.4–9.1).

3.9 Public hospitals

The percentage of people who had utilised a public hospital was identified from the NZHS 2002/03 as those who stated they had used a service at, or been admitted to, a public hospital in the last 12 months. As shown in Table 16, in Auckland DHB Maori males and females and Pacific females tended to be high hospital users. Table 16 Percentage of people who utilised a public hospital in the past 12 months

DHB Public hospital utilisation: age-standardised prevalence (%) Males Females Total M P A O T M P A O T M P A O T Auckland 20.5 10.3 9.1 20.4 17.6 25.7 28.6 14.2 23.0 22.2 23.3 20.4 11.8 21.8 20.0 Counties– 20.2 13.3 10.5 18.6 17.0 28.3 26.0 26.7 24.9 25.8 24.6 20.0 19.1 21.9 21.6 Manukau Waitemata 16.5 9.5 6.6 19.6 17.7 18.3 27.9 13.4 22.8 21.8 17.5 19.7 10.3 21.2 19.8 Northland 20.5 13.9 8.6 21.2 20.8 28.5 21.5 33.3 25.8 26.6 24.9 16.7 23.5 23.6 23.8 New Zealand 20.6 14.4 10.9 19.7 19.1 27.8 26.2 17.9 24.9 24.9 24.4 20.6 14.7 22.4 22.1

A greater proportion of people in Auckland DHB (20%) and nationally (22.1%) utilised a public hospital than in Waitemata (19.8%), although results were not statistically significantly different. Females in all regions shown were more likely to utilise public hospitals (24.9%) than males (19.1%), and this difference was significant between males and females in Auckland DHB (males 17.6%, females 22.2%) and nationally.

In Auckland DHB Maori (23.3%) and Other (21.8%) were more likely to utilise a public hospital than Pacific (20.4%) and Asian (11.8%) although differences were not significant, except among European/Others and Asian ethnic groups. Females were more likely than males to utilise public hospital services in all ethnic groups (males 17.6%, females 22.2%), although this difference was greatest for Maori (males 20.5%, females 25.7%) and Pacific (males 10.3%, females 28.2%).

Table 17 and 17A show the distributions of hospital discharges, case weights and bed days by wards as acute and electives. Avondal-Roskill and Tamaki-Maungakiekie wards reported higher proportions than their population proportions on hospital discharges, case weights and bed days. However, the other five wards showed lower percentages on all the previously mentioned parameters. It is well known fact that Avondale-Roskill and Tamaki-Maungakiekie wards are highly populated with Maori, Pacific People and other ethnic minorities and they are also the most deprived areas in Auckland City. Table 17 Auckland city wards populations by hospital discharges, case weights and bed days, year 2007. e l p o e p e

g 0 r d s 0 a n e 1 h

a g r l c r e k s a i c p

h D u

s c e l A d e s

i e p e g l t s d r m o

p h y a e o s d o a r g h p e e i f e

d

t c g

e p 0 s r s n h

d i 0 e a W o g 0 e

i 1 i s D g h 0

t

e r e B y r c 1 a

d s

a l a f e s w r e i a h u d o p t e

e c D C p h

s d e p s s f f o g i e e g a i s o o p a D g b c e y

t t t r f f d f a n n n a W r o o o

e e e D a h d e c c c c r m m s m d r r r W s a

e i a u e u e u e W % S P D S P C S P B Avondale-Roskill 23% 18,005 24% 19 15,973 25% 16 47,147 25% 49 Eastern bays 11% 7,354 10% 15 6,693 11% 14 19,971 11% 41 Eden-Albert 14% 9,536 13% 16 7,644 12% 12 21,913 12% 36 Hauraki Gulf 2% 1,301 2% 14 1,403 2% 15 4,102 2% 45 Hobson 20% 10,621 14% 13 8,826 14% 10 24,822 13% 29 Tamaki-Maungakiekie 20% 20,380 28% 24 17,119 27% 20 50,270 27% 58 Western bays 10% 6,761 9% 16 5,784 9% 14 17,026 9% 41 Total 100% 73,958 100% 63,442 100% 185,251 100% e l

p d Table 17A o e n a p e l

Acute g k 0 r c s 0 a e 1 u h

g r A c r

e l s a i p a

h t D

s c o e l t d e s

i e p e g l t d s r m o

p h y a e o s d o a r g h p e e i f e

d

t c g e 0 p r s n s h

d i 0 a W e o g 0 e

i 1 i s D h 0 g t

e e y B r r c 1 a

d s

l a f a e w s r e

i a u d o h p t e

e C D p c h

e p s d s s f f o g i e e g a i s o o p d g b a c e y

t t t r d f f f a n n n a W r o o o

e e e D a h d e c c c c r m m s m d r r r W s a

e i a u e u e e u W % S P D S P C S P B Avondale-Roskill 23% 14,929 24% 15 12,576 25% 13 42,918 25% 44 Eastern bays 11% 6,318 10% 13 5,441 11% 11 18,341 11% 38 Eden-Albert 14% 8,173 13% 13 6,150 12% 10 20,153 12% 33 Hauraki Gulf 2% 967 2% 11 993 2% 11 3,422 2% 37 Hobson 20% 9,425 15% 11 7,470 15% 9 23,042 14% 27 Tamaki-Maungakiekie 20% 17,415 28% 20 13,770 27% 16 45,795 27% 53 Western bays 10% 5,835 9% 14 4,703 9% 11 15,637 9% 38 Total 100% 63,062 100% 0 51,103 100% 0 169,308 100% 40 Elective Avondale-Roskill 23% 3,076 28% 3 3,397 28% 4 4,229 27% 4 Eastern bays 11% 1,036 10% 2 1,252 10% 3 1,630 10% 3 Eden-Albert 14% 1,363 13% 2 1,494 12% 2 1,760 11% 3 Hauraki Gulf 2% 334 3% 4 410 3% 4 680 4% 7 Hobson 20% 1,196 11% 1 1,356 11% 2 1,780 11% 2 Tamaki-Maungakiekie 20% 2,965 27% 3 3,349 27% 4 4,475 28% 5 Western bays 10% 926 8% 2 1,081 9% 3 1,389 9% 3 Total 100% 10,896 100% 12,340 100% 15,943 100% 3.10 Private hospitals

The percentage of people who had utilised private hospital services was identified from the NZHS 2002/03 as those who had used a service at, or been admitted to, a private hospital in the last 12 months is shown in Table 18. It is difficult to interpret the result with small numbers. However the Auckland DHB rate was slightly higher than the national rate, 6.3% and 5.9% respectively. Table 18 Percentage of people who utilised a private hospital in the past 12 months

DHB Private hospital utilisation: age-standardised prevalence (%) Males Females Total M P A O T M P A O T M P A O T Auckland ND ND ND 6.7 5.1 2.9 ND 5.4 8.9 7.4 1.6 4.3 3.2 7.8 6.3 Counties– 4.2 ND ND 6.7 4.9 3.7 ND ND 6.3 4.2 3.9 ND ND 6.5 4.5 Manukau Waitemata ND ND ND 7.2 6.0 5.4 ND 5.1 9.1 8.2 3.0 5.2 3.0 8.2 7.2 Northland 2.7 ND ND 6.6 5.6 3.1 ND ND 5.0 4.4 2.9 ND ND 5.8 5.0 New Zealand 2.9 2.9 ND 6.0 5.3 3.1 1.9 4.2 7.3 6.4 3.0 2.4 2.6 6.7 5.9

As shown in Table 18, Counties–Manukau DHB had the smallest proportion of people who had utilised private hospital services (4.5%) compared with Northland (5.0%), Auckland (6.3%), Waitemata (7.2%), and nationally (5.9%), although the only significant difference was between Counties–Manukau and Waitemata. In Auckland, Waitemata, and nationally, females were more likely to utilise private hospital services than males, but in Counties–Manukau and Northland this trend was reversed. However the differences between males and females were not significant.

Within Auckland DHB, Others (7.8%) were more likely than Asian (3.2%) or Maori (1.6%) to utilise private hospital services, with males in the Other ethnic group being a little less likely to do so than females (males 6.7%, females 8.9%). However difference was not significant.

3.11 Complementary and alternative medicine providers

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) healthcare providers include providers not generally considered part of the mainstream health system. Overall, one in four adults (21.9%; 20.2–23.6) had seen a CAM healthcare provider in the last 12 months. Females (26.5%; 24–29) were significantly more likely than males (16.9%; 14.8–19.0) to have seen a CAM healthcare provider in the last 12 months.

In both males and females, European/Other and Maori ethnic groups were more likely than Pacific and Asian ethnic groups to have seen a CAM healthcare provider in the last 12 months.

Nationally, among all adults, the most common types of CAM healthcare provider visited were: massage therapists (9.1%; 8.3–9.9) chiropractors (6.1%; 5.6–6.7) osteopaths (4.9%; 4.3–5.5) homeopaths or naturopaths (4.5%; 3.9–5.0).

3.12 Other providers

Nationally, six out of 10 adults (60.9%; 59.6–62.1) had seen other types of healthcare providers in the past 12 months. Among adults who had seen other types of healthcare providers, the most common types seen were dentists or dental therapists, opticians or optometrists, and physiotherapists.

3.12.1 Dentists and dental therapists

Overall, four out of 10 adults (40.4%; 39.1–41.7) had seen a dentist or dental therapist in the last 12 months. Females (44.8%; 42.9–46.6) were significantly more likely than males (36.8%; 35.1–38.6) to have seen a dentist or dental therapist in the last 12 months. In both males and females, European/Other were significantly more likely to have seen a dentist or dental therapist in the last 12 months than other ethnic groups.

3.12.2 Opticians and optometrists

Nationally, one in five adults (18.4%; 17.3–19.4) had seen an optician or optometrist in the last 12 months. Females (20.4%; 18.8–22.0) were significantly more likely than males (14.0%; 12.5–15.6) to have seen an optician or optometrist in the last 12 months. In both males and females, European/Other were significantly more likely to have seen an optician or optometrist in the last 12 months than Maori and Pacific ethnic groups.

3.12.3 Physiotherapists

Overall, one in seven adults (14.8%; 13.9–15.6) had seen a physiotherapist in the last 12 months. There was no significant difference in the proportion of males (15.6%; 13.9–17.4) and females (14.6%; 13.2–16.0) who had seen a physiotherapist in the last 12 months. European/Other males and females were most likely to have seen a physiotherapist in the last 12 months, followed by Maori, Pacific and Asian males and females.

3.12.4 Telephone helplines

Overall, one in six adults (15.5%; 14.5–16.6) had used a telephone helpline in the last 12 months. Females (20.9%; 19.3–22.6) were significantly more likely than males (9.8%; 8.5–11.14) to have used a telephone helpline. In males, there were no significant differences between ethnic groups in the use of telephone helplines. European/Other and Maori females were significantly more likely than Pacific and Asian females to use telephone helplines.

Among adults who had used a telephone helpline, the most common services used were: GP’s nurse (55.5%; 52.2–58.7) Quitline (13.4%; 11.1–15.7) after-hours medical centre (9.3%; 7.4–11.2) accident and emergency (8.2%; 6.3–10.1) Plunketline (7.9%; 6.4–9.5).

4. Reasons for visiting the health providers

4.1 Reasons for visiting general practitioner

Overall, the most common reasons for seeing a GP were a short-term illness or temporary condition, a routine check-up or health advice, a chronic condition or disability, or an injury or poisoning.

Overall, a GP wrote a prescription for seven out of 10 adults (69.2%; 67.8–70.5) on their last visit. Females (70.9%; 69.2–72.6) were significantly more likely than males (66.5%; 64.0–68.9) to have received a prescription from the doctor on their last visit.

4.2 Health checks

Overall, in the last 12 months: one in two adults (52.0%; 50.7–53.3) had their blood pressure measured one in four adults (25.1%; 24.2–26.0) had their cholesterol tested one in six adults (17.8%; 16.7–18.9) had a diabetes test one in five adults (19.8%; 18.8–20.8) had a flu injection and six out of 10 adults aged 65 years and over (60.5%; 57.8–63.2) had a flu injection one in seven males (14.3%; 13.1–15.5) had a blood test for prostate cancer and over one-third of males aged 65 years and over (37.9%; 33.6–42.2) had a blood test for prostate cancer

one in 13 adults (7.9%; 7.3–8.5) had been counselled about smoking.

Females were significantly more likely than males to have had their blood pressure measured, whereas males were significantly more likely to have had their cholesterol tested. There was no significant difference in the proportion of males and females who had had a diabetes test or flu injection or been counselled about smoking.

A routine check-up was the most common reason Maori males and females gave for visiting a Maori health provider. The most common reasons Pacific adults gave for seeing a healthcare worker at a Pacific health provider were: a routine check-up or health advice (51.1%; 35.6–66.6) a short-term illness or temporary condition (27.4%; 7.7–47.1) a disability, long-term illness or chronic condition (15.4%; 4.7–26.0).

The most common reasons for visiting a pharmacy or chemist were: collected a prescription for themselves (76.9%; 75.6–78.2) purchased a non-prescription medicine (excluding medicines that had to be signed for) (41.9%; 40.5–43.3) collected a prescription for someone else (41.1%; 39.8–42.4) got advice on non-prescription medicines (22.6%; 21.3–23.8) purchased vitamin or herbal supplements (19.9%; 18.9–21.0).

4.3 Prescriptions

Nationally, seven out of 10 adults (71.8%; 70.6–73.0) said they had received a prescription for themselves in the last 12 months. Females (77.7%; 76.3–79.2) were significantly more likely than males (64.7%; 62.6–66.8) to have received a prescription in the last 12 months. In males, there were no significant differences between ethnic groups in the proportion receiving a prescription in the last 12 months. Asian females were significantly less likely than European/Other and Pacific females to have received a prescription in the last 12 months.

Among adults who had a prescription in the last 12 months, 48.1% (46.7–49.4) had one to four items, 15.9% (14.8–17.0) had five to nine items, and 36.1% (34.8–37.4) had 10 or more items.

Among adults who had received a prescription for themselves in the last 12 months, 17.2% (15.9–18.5) did not collect one or more of the items from the chemist or pharmacy. Females (21.4%; 19.4–23.5) were significantly more likely than males (13.5%; 11.6–15.4) to have not collected a prescription item. Maori males were significantly more likely than European/ Other and Asian males to not collect one or more of their prescription items in the last 12 months. European/Other, Maori and Pacific females were significantly more likely than Asian females not to collect a prescription item. The proportion of males and females who did not collect one or more of their prescription items in the last 12 months declined with age, particularly in females. The most common reasons given for seeing a practice nurse as part of a GP consultation were: blood test (38.2%; 35.7–40.7) immunisation or vaccination (18.9%; 17.0–20.7) cervical smear (females, 13.0%; 11.1–14.9) bandaging (11.6%; 9.9–13.3) health advice (8.6%; 7.2–9.9).

The most common reasons given for seeing a nurse without seeing a GP at the same time were: immunisation or vaccination (24.9%; 22.3–27.5) blood test (18.6%; 16.4–20.9) cervical smear (females, 16.9%; 14.2–19.6) health advice (10.0%; 8.0–12.1) bandaging (9.6%; 7.9–11.3).

Nationally, among all adults, the most common types of CAM healthcare provider visited were: massage therapists (9.1%; 8.3–9.9) chiropractors (6.1%; 5.6–6.7) osteopaths (4.9%; 4.3–5.5) homeopaths or naturopaths (4.5%; 3.9–5.0).

Overall, the most common reasons for seeing a CAM healthcare provider were: a disability, long-term illness or chronic condition (32.5%; 30.3–34.8) a short-term illness or temporary condition (28.3%; 26.1–30.6) an injury or poisoning (23.9%; 21.5–26.3).

Among adults who had used a telephone helpline, the most common services used were: GP’s nurse (55.5%; 52.2–58.7) Quitline (13.4%; 11.1–15.7) after-hours medical centre (9.3%; 7.4–11.2) accident and emergency (8.2%; 6.3–10.1) Plunketline (7.9%; 6.4–9.5).

5. Barriers to visit

5.1 Experience of barriers to usage of general practitioners

A survey of Auckland City residents in 2004 found that a fifth (20%) reported that, in the preceding 12 months, there had been at least one instance when they had wanted to visit a doctor but had not done so. Groups least likely to have visited a GP when they wanted to were Maori (nearly 30%) and people with an income of between $70,001–$100,000.

The highest proportion of residents experiencing these barriers was in Avondale- Roskill (27%). The lowest proportion was those living in Eastern Bays (6%).

Older people were the least likely to say that they experience barriers to visiting a GP. Younger people, in the 15–24 year age group, were most likely to say that they had experienced barriers to visiting a GP.

Nearly one-third of Maori (32%) said that they had experienced barriers to using a GP at least once in the preceding 12 months. Europeans were least likely to have experienced barriers (17%).

There was little difference in the experience of barriers between the genders, with one-fifth of both males (21%) and females (20%) having experienced barriers.

Those with a high household income, of $100,001 or more, were least likely to have experienced barriers to visiting a GP at least once in the preceding 12 months (11%). Of the other four income groups, those with an annual household income of between $70,001 and $100,000 were most likely to have experienced barriers (27%). 5.2 Barriers to usage of general practitioners

Cost was the most common reason identified by those who had not visited their GP when they wanted to (56%). Other reasons included being too busy (17%), or the condition improving on its own (9%).

Across all wards with the exception of Hauraki Gulf, cost was the most dominant reason identified by residents who had not visited their GP when they wanted to. Of the four groups, residents aged 25–49 years were most likely to identify cost as a barrier to visiting their GP (59%) and to say that they were too busy to go to the doctor/couldn’t take time off work (19%).

Cost was more likely to be a barrier for females to visiting a GP (65%), than males (45%). By contrast, males were more likely to respond that they were too busy/couldn’t take time off work (20%, compared with 13% of females) and that the problem got better on its own (12%, compared to 7% of females).

Those with a household income of $70,001–$100,000 were most likely to cite cost as a barrier (74%) to visiting a GP. Residents with a household income of $50,001– $70,000 were most likely to say that they had been too busy/couldn’t take time off work.

The most common reasons given by Maori adults for not being able to see a Maori health provider when needed were: . “couldn’t get an appointment soon enough or at a suitable time or it was after hours” (33.3%; 18.5–48.1) . “had no transport to get there” (31.5%; 16.5–46.6) . “I couldn’t spare the time” (11.5%; 4.1–18.8) . “didn’t want to make a fuss or couldn’t be bothered” (18.7%; 3.0–34.4) . “couldn’t get in touch with the provider” (15.8%; 6.8–24.9) . “costs too much” (12.2%; 3.2–21.2). . Among the few Pacific adults who reported an unmet need for a Pacific health provider, the most common reasons given were: . “couldn’t get in touch with the provider” . “none in my area” . “couldn’t get an appointment soon enough or at a suitable time or it was after hours” . “had no transport to get there”.

Overall, the most common reasons for not collecting a prescription item were: . “costs too much” (26.9%; 23.8–29.9) (this should be reduced after PHO implementation) . “will pick up medication if needed or prescription written just in case” (21.1%; 17.7–24.4) . “can only pick up one month’s prescription at a time” (16.4%; 13.2–19.6) (should be reduced after the application of three months prescription mediciations) . “condition got better by itself” (16.1%; 13.0–19.2) . “don’t like taking drugs” (11.0%; 8.6–13.5). The proportion of males and females who did not collect one or more of their prescription items in the last 12 months did not vary significantly across NZDep01 quintiles.

6. Characteristics of GP visits “NatMedCa MOH, 2001 / 02”

6.1 Characteristics of patients

Nearly 50% of the visiting patients hold either Community Cards or High Utilisation Health Card. Table 19 shows this distribution

Table 19: Percentage distribution of all patients, by ethnicity and card status Total* Card status No card 51.6 CSC 41.6 HUHC 2.8 Both cards 2.3 Missing 1.8 Total 100%

Table 20 summarises three measures of social well-being. Social support was judged to be good or very good in 75.7% of patients and poor or very poor in only 5.5%. The area measure of deprivation (NZDep01) by decile was fairly evenly spread, with just a suggestion that people from poorer areas consult more frequently. Approximately 4% of patients were not fluent in English.

Table 20: Social support, NZDep2001 of residence, and fluency in English: percentage of all patients Whole survey Social support 5. Very good 47.7 4. Good 28 3. Average 15.5 2. Poor 4.8 1. Very poor 0.7 Unknown 3.3 Total 100% Quintile Q1 20.6 Q2 20 Q3 19.8 Q4 20 Q5 19.7 Total 100% % Not fluent in English 4.00% The distribution of numbers of visits reported by patients is presented in Table 21. The largest percentage of patients (16.9%) reported only one visit to the GP in the previous year, and two-thirds reported six or fewer visits in that time. Ten or more visits were reported by more than a fifth (21.4%) and the largest number reported was 154 (almost three per week). The mean number of visits reported for the previous year was 6.6. Table 21: Patient-reported number of visits to practice in previous 12 months: percentage distribution

Number * Total 1 16.9 2 9.7 3 10.5 4 10.6 5 8.2 6 9.2 7 4.5 8 6 9 3 > 9 21.4 Total 100% Mean 6.6

Table 22 shows the source and type of payment. Most of the visits, 88.3%, were paid by cash or GMS. However, ACC payment was for 9.4% and maternity visits at 2.3%. Table 22: Source and type of payment cited, as percentage of visits

Source of payment* Total % visits cash/ GMS 88.3 Under 6 (Y) 17.9 Child, card (J1) 4.6 Child, no card (J3) 5.9 Adult, card (A1) 36.2 Adult, no card (A3) 35.7 Total cash/GMS 100% % visits ACC payment 9.4 % visits maternity care 2.3 Total 100%

Mean visit duration was 14.9 minutes and varied little across practice types (Table 23). Two-thirds of visits took between 10 and 15 minutes, while about a tenth lasted beyond 20 minutes. Table 23: Duration of visit: percentage distribution

Duration Total Shorter < 10 minutes 12 Average 10–15 minutes 61.7 Longer 15–20 minutes 15 Longest > 20 minutes 11.3 Mean duration (minutes) 14.9 About one in 20 visits was judged very urgent (ASAP) and an additional third required same-day attention (Table 24). About one-sixth allowed latitude of one month. About one in fifty visits included life-threatening problems (these were defined to include acute problems, such as sudden chest pain, or new symptoms of serious import, such as rectal bleeding, but to exclude serious conditions already being managed). Fully a third of visits were judged to be for conditions that were self-limiting, even though the most serious of multiple problems was scored.

Figure 24: Urgency and severity of visit: percentage distribution

Total Urgency 4. ASAP 5.1 3. Today 32.6 2. This week 43.5 1. This month 18.7 Total 100% Severity 4. Life-threatening 2 3. Intermediate 41 2. Self-limiting 34.4 1. Not applicable 22.6 Total 100% An additional measure of the significance of the visit is the patient’s level of disability (Table 25). Among those for whom data were provided, 33.9% had no disability. Among those with disability, for only a quarter was it permanent. For 67.4% of those with a disability, the effect was minor and temporary (affecting 43% of all patients). In this same group, 9.3% had a major, permanent disability (accounting for 6% of patients overall). Table 25: Level of disability as percentage distribution

Level of disability Total None 33.9 Minor 55.1 Major 11 Total 100% Temporary 75.1 Permanent 24.9 Total 100% Minor temporary 67.4 Major temporary 7.8 Minor permanent 15.6 Major permanent 9.3 Total 100% Table 26 shows the frequency of reason for visit (RfV) grouped by READ2 chapter (first digit level). The first column gives the occurrence of any reason cited in each grouping as a percentage of all visits, and the second gives their frequency as a percentage of all reasons. Where possible, an item is attributed to an anatomical system (e.g. musculoskeletal) or process (e.g. cancer) recognised by the initial alphabetical digit of the READ code; a considerable number of RfV were actions (e.g. examination or prescription) or non-specific symptoms identified by numerical codes. In the table, sub-chapter headings (identified by the second digit of the code) are included if they reach a frequency of 0.5%.

The largest grouping of RfV was “Actions”, which made up 20.3% of all RfV and were reported at 25.8% of visits. Within this large category, therapeutic procedures accounted for 8.4% of RfV, preventive procedures for 5.8%, operations for 3.5%, and administrative activities for 2.5%.

Non-specific symptoms accounted for 12.4% of RfV and occurred at 16.7% of visits. Investigations, including history and examination, made up 7.7% of RfV and occurred at 10.7% of visits.

The most common system-based grouping was Respiratory. Respiratory RfV made up 12.5% of RfV and occurred at 17.1% of visits. The commonest sub-chapters were respiratory symptoms at 7.1% of RfV, infections at 2.7%, chronic obstructive airway disease at 1.1%, and pneumonia and influenza at 0.9%.

Other systems reported frequently as RfV were musculoskeletal (7.2%), nervous system (7%), skin (4.5%), digestive (4.3%), genito–urinary (3.8%) and cardiovascular (3.7%). Injury or poisoning made up 4.8% of RfV. In general, the percentage of visits at which each category was recorded was about a third higher than the percentage of all visits; no group seemed to have a much greater tendency to occur alone (as represented by a narrower than average gap between the rate per 100 visits and the percentage of RfV). Table 26: Distribution of reasons-for-visit chapters and sub-chapters RfV grouping, READ2 chapters and sub-chapters* RfV RfV grouping as % of grouping, reasons % of visits Actions 25.8 20.3 Therapeutic procedures 8.4 Preventive procedures 5.8 Operations 3.5 Administration 2.5 Respiratory 17.1 12.5 Respiratory symptoms, COPD, Pneumonia and Influenza 7.1, 2.7, 1.1, 0.9 Symptoms non-specific 16.7 12.4 Investigations 10.7 7.7 Musculoskeletal / connective tissue 9.8 7 Rheumatism, excluding the back, vertebral column syndroms, Arithropathies 2.5, 2.5, 1.9 Nervous system / sense organs 9.7 7 Central nervous system (CNS) symptoms ear diseases, disorders of eye 3.6, 1.7, 1.1 Injury/poisoning 6.7 4.8 Abrasions, sprains and strains 0.5, 0.5 Unspecified conditions 6.3 4.5 Skin / subcutaneous tissue 6.2 4.5 Digestive 6 4.3 Genito-urinary 5.2 3.8 Cardiovascular/circulatory 4.9 3.7 Cardiovascular symptoms, blood pressure 1.4, 1.2 Mental 3.2 2.4 Neurotic, personality, other non-psychotic disorders, Non-organic psychoses 1.3,1 Infectious/parasitic 2.2 1.6 Viral and chlamydial diseases 0.8 Endocrine/nutritional/metabolic/immunity 2.1 1.5 Cancers/neoplasms 1.7 1.2 Benign neoplasms 0.8 Pregnancy/childbirth/puerperium 0.2 0.2 Congenital 0.2 0.1 Blood / blood-forming organs 0.2 0.1 Perinatal 0.01 0.01 Not coded 0.4 0.3 100%

Table 27 classifies RfV by “components” (i.e. type of reason rather than anatomical system implicated). RfV were most commonly symptoms (31.2%), diseases (31.3%) or treatments (12%). Table 27: Comparison of reason for visit components as percentage of all reasons

RfV component Total Disease 31.3 Symptoms 31.2 Treatments 12 Investigations 7.7 Prevention 5.8 Injury/poisoning 4.8 Administrative 2.5 Unspecified conditions 4.5 Not coded 0.4 Total 100%

The visit form made provision for recording up to four diagnoses/ problems, and GPs were encouraged to include all sorts of problems, including well-person care, psycho- social difficulties and practitioner-identified issues, as well as defined pathology. The term “problem” is used hereafter, rather than the more traditional “diagnosis”. Table 28 gives the distribution of the number of problems per visit. Almost 56% of patients had a single problem, about 27% had two, 12% three and 6% four. The mean number of problems was close to 1.7 per visit for each type of practice.

Table 28: Percentage distribution of number of problems per visit

Number of problems Total No problem 0.3 1 problem 55.5 2 problems 26.6 3 problems 11.7 4 problems 5.9 Total 100% Mean number of problems 1.67

Table 29 shows the frequency of problems grouped by READ2 chapter (first digit level). The first column gives the occurrence of any problem in the grouping as a percentage of visits, the second gives their frequency as a percentage of all problems, and the third gives their frequency as a percentage of new problems. As with RfV, where possible an item is attributed to an anatomical system (e.g. musculoskeletal) or process (e.g. cancer), recognised by the initial alphabetical digit of the READ2 code; a significant number of problems could not be attributed in this way and are presented under Actions, Investigations or Non-specific symptoms. In the table, sub-chapter headings (identified by the second digit of the code) are included if they reach a frequency of 0.5% of all problems.

Respiratory problems were the most common at 14.7% of all problems, followed by actions at 11.3%, cardiovascular at 9.2%, nervous system and sense organs at 8.2%, injury/poisoning at 7.1%, skin at 6.7%, musculoskeletal at 5.7% and investigations at 5.3%.

Groups of problems at the sub-chapter level that reached a threshold of 3% included acute respiratory infections (7.9%), preventive procedures (5.5%), hypertensive disease (4.6%), ear diseases (3.8%) and chronic obstructive airways disease (3.2%).

Many categories of problem were less frequent as new problems, indicating they were commonly followed up. However, respiratory, nervous system, injury, skin, infections, genito-urinary and non-specific symptoms appeared relatively more frequently as new problems. Table 29: Distribution of problems managed, by READ2 chapter and sub-chapter

Problem grouping, by READ2 chapter* Problem Percent of all Percent of grouping – problems new % of visits problems

Respiratory 22.8 14.7 23.1 Acute respiratory infections 7.9 16.7 Chronic obstructive airways disease 3.2 0.9 Pneumonia and influenza 1.4 2.4 Respiratory symptoms 1.2 1.9 Actions 17 11.3 5.7 Preventive procedures† 5.5 3 Operations 2.3 1.2 Therapeutic procedures 1.9 0.5 Administration 1.1 0.8 Cardiovascular/circulatory 13.7 9.2 3.1 BP hypertensive disease 4.6 0.6 Arteriosclerotic heart disease 1.5 0.3 Cardiovascular symptoms 0.5 0.9 Nervous system / sense organs 13.2 8.2 10 Ear diseases 3.8 5.3 Disorders of eye and adnexa 1.6 2.4 CNS symptoms 1.4 1.5 Injury/poisoning 11.6 7.1 10.1 Sprains and strains of joints and adjacent muscles 2.4 3.7 Abrasions 0.6 1 Contusions 0.6 1.1 Skin / subcutaneous tissue 10.7 6.7 9.3 Dermatitis/dermatoses 2.5 3.1 Skin and subcutaneous tissue infections 1.4 2.5 Musculoskeletal / connective tissue 8.9 5.7 4.4 Arthropathies and related disorders 2.1 1.1 Rheumatism, excluding the back 1.7 1.8 Vertebral column disorders 1.4 1.2 Osteopathy/chondropathy / acquired musculoskeletal deformity 0.5 0.4 Investigations 8.5 5.3 4.2 History 2.5 1.7 Examination 1.7 1.8 Diagnostic procedures/ lab test / radiology 1.2 0.8 Mental 7.7 4.9 3.1 Neurotic, personality and other non-psychotic disorders 2.5 2.2 Non-organic psychoses 2.3 1 Genito-urinary 7.4 4.6 5.3 Female genital tract disorders 1.4 1.2 Urinary system diseases 1.3 1.9 Genito-urinary symptoms 0.8 0.9 Digestive 7.2 4.4 4.5 Duodenal diseases 1.5 1.1 Gastro-intestinal tract (GIT) symptoms 1.2 1.9 Diseases of intestines and peritoneum 0.5 0.4 Infectious/parasitic 6.8 4.3 7.1 Viral and chlamydial diseases 1.3 2 Mycoses 1 1.6 Bacterial food poisoning 0.9 2 Viral diseases with exanthema 0.5 0.7 Endocrine/nutritional/metabolic/immunity 6.1 4 1 Endocrine gland diseases, including goitre 2.2 0.4 Metabolic and immunity disorders 1.7 0.4 Symptoms non-specific 5.6 3.5 4.2 Ear, nose and throat symptoms 0.5 0.9 Cancers/neoplasms 3.9 2.4 2.5 Benign neoplasms 0.8 1.2 Unspecified conditions 3.8 2.3 1.5 Health status and contact with health services factors 2.1 1.4 Blood / blood-forming organs 0.8 0.5 0.3 Pregnancy/childbirth/puerperium 0.5 0.3 0.3 Congenital 0.3 0.2 0.1 Perinatal 0.06 0.03 0.05 Not coded 0.7 0.4 0.3 Total 100% 100% The visit questionnaire provided space to record the type of problem. New problems made up around 35% of all problems and short-term follow-up 15%. Long-term follow-up accounted for 23%, long-term with flare-up 8%, and preventive 5% (table 30). Table 30: Comparison of percentage of problem status across practice types

Status Total New problem 34.8 Short-term follow-up 14.5 Long-term follow-up 23.2 Long-term with flare-up 8 Preventive 4.9 (Not given) 14.5 Total 100% Infectious diseases were similar across the genders and decreased after the 25- 34 age group, being much the highest in childhood and early adulthood. Digestive problems had a stable occurrence across age groups and between genders. Endocrine problems manifested most frequently across age groups 45-74 and were similar for both males and females. Problems related to neoplasia increased progressively after the twenties; rates were similar across the genders.

The reason for visits and seasonality is shown in table 31. The only condition showed seasonality was respiratory related diseases, mostly in winter.

r ) )

Table 31: Seasonal variation: groups of problems as a percentage of all problemsy r e n r e b t a ) m ) r n u m u i g r e t e n b Problem grouping w u i v ( m e r

a o t ( F p m

s N s

u y o ( u t s o a

g ( t r

M u r

e e A o b

t b

o m t h m

e c e e c r t n e a p u D e M J S

(READ2 chapter) Respiratory 14.7 18.4 14.9 10.3 Actions 12.9 9.2 11 12.1 Cardiovascular 9.2 9.3 9 9.5 Nervous / sense organs 8.1 8.3 8.6 7.7 Injury/poisoning 7 7.6 7.2 6.8 Skin / subcutaneous tissue 6.9 5.7 6.3 8 Musculoskeletal 5.4 4.7 6.9 5.8 Investigations 5.2 5.1 5.2 5.9 Mental 4.9 5.1 3.9 5.8 Digestive 4.6 4.2 4.7 4 Genito-urinary 4.2 4.7 4.4 5.2 Endocrine/nutritional, etc. 3.9 4.9 3.6 3.7 Symptoms non-specific 3.8 2.8 3.8 3.5 Infectious/parasitic 3.6 4.6 4.2 4.8 Unspecified conditions 2.3 1.9 2.4 2.6 Cancers/neoplasms 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.9 Blood / blood-forming 0.4 0.3 0.5 0.5 Pregnancy/childbirth, etc. 0.3 0.3 0.2 0.3 Congenital 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.3 Perinatal 0.1 0 0 0.1 Not coded 0.3 0.5 0.7 0.2 Total 100% 100% 100% 100% 6.2 Laboratory Tests and Other Investigations

The visit questionnaire recorded laboratory tests and other investigations; Table 32 shows the categories used. A test or investigation was ordered in 24.8% of visits and a laboratory test was ordered for 17.2%. The frequencies of the different types of laboratory tests were: haematology 9.1%, biochemistry 11.0%, and other laboratory 5.3%. Imaging was ordered at 4.1% of visits, and other non-laboratory at 8.2%. Table 32: Rate per 100 visits at which tests and investigations were ordered

Test group* Rate per 100 Test sub-group

Any laboratory test 17.2 Haematology 9.1 8.7 Full blood count 3.8 Sed rate 2.9 Fe, B12, folic acid Biochemistry 11 5.4 Serum glucose 6 Creatinine/urea 5 Liver function 5.1 Lipids 4.1 Thyroid 3.6 Other chemistry Other 5.3 4.1 Culture 1.9 Pap smear Imaging 4.1 2.9 Plain X-ray 0.1 Contrast 1.2 Ultrasound Other 8.2 0.4 ECG 0.1 Spirometry 7.8 Other Any test/investigation 24.8

6.3 Pharmacological Treatment

This section analyses the treatments recommended. First the frequency of drug and non-drug treatments is given, then the types of drug are described.

Space was provided on the visit report for up to four problems, but any number of drugs could be entered. Drugs were classified according to the Pharmacodes/ATC system. The purpose-designed software mentioned in the Methodology section was used to code each item. Note (Table 33) that a prescription was given at 66.2% of visits, and “other treatments” were recorded at 62% of visits. Both pharmacological and “other treatments” together were recorded at 36.2%. No treatment was recorded at 8% of visits. Table 33: Percentage of visits at which treatments were given, by treatment modality and practice type

Treatment All visits No treatment 8.0% Prescription only 30.0% Other treatments only 25.9% Both types of treatment 36.2% Total 100.0%

Table 34 shows the frequency of use of drugs types, by level 1 group, as the percentage both of prescription items and of all visits. Systemic anti-infectives were the commonest drugs reported, making up 18.4% of script items and being prescribed at 21.6% of all visits. Other common groups were nervous system drugs (14.4% and 15.8%), cardiovascular system drugs (13.1% and 10.8%), respiratory system drugs (10.8% and 10%) and alimentary tract drugs (8.4% and 8.8%). Each group is considered below. Table 34: Distribution of drugs, by group (Pharmacodes/ATC level 1)

Drug group Percent of all Percent of all Rate per 100 – all prescription items visits visits Infections agents for systemic use 18.4 21.6 23.7 Nervous system 14.4 15.8 18.6 Cardiovascular system 13.1 10.8 17 Respiratory system and allergies 10.8 10 14 Alimentary tract and metabolism 8.4 8.8 10.9 Musculoskeletal system 6.4 7.6 8.3 Blood and blood-forming organs 6.1 6 7.8 Dermatologicals 5.9 6.4 7.7 Systemic hormone preparations 4.4 5.3 5.7 Genito-urinary system Sensory organs 3.7 4 4.8 Extemporaneously compounded preparations and galenicals 1.3 1.6 1.7 Oncology agents and immunosuppressants 1 1.1 1.3 Special foods Medication non-specific 0.3 0.3 0.4 0.1 0.1 0.1 5.6 6.8 7.2 Total 100%

Table 35 gives the distribution of the most frequently prescribed drug sub-groups at the second level of grouping. Anti-bacterials head the list, being prescribed at a rate of 21.9 per 100 visits and making up 17.0% of prescription items. The next most frequent were analgesics, prescribed at a rate of 9.8 per 100 visits and making up 7.6% of prescription items. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, most commonly used as analgesics, were used at a rate of 6.7 per 100 visits and made up 5.2% of scripts.

Table 35: Most frequently prescribed drug subgroups Drug sub-group (Pharmacodes/ATC level 2)* % of script items Per 100 visits Anti-bacterials 17 21.9 Analgesics 7.6 9.8 Anti-inflammatory non-steroidal drugs (NSAIDs) 5.2 6.7 Inhaled corticosteroids 3.5 4.5 Diuretics 3.4 4.4 Agents affecting the renin-angiotensin system 3.3 4.2 Anti-depressants 3.1 4 Beta-adrenoceptor agonists (tablets) 2.9 3.7 Corticosteroids topical 2.8 3.6 Anti-thrombotic agents 2.7 3.5 Beta adrenoceptor blockers 2.6 3.3 Anti-ulcerants 2.5 3.2 Lipid-modifying agents 2.1 2.6 Calcium channel blockers 1.9 2.4 Corticosteroids and related agents 1.8 2.3 Diabetes and diabetes management 1.6 2.1 Contraceptives hormonal 1.5 1.9 Anti-histamines 1.5 1.9 Nitrates 1 1.2 Laxatives 1 1.3

6.4 Non-drug Treatments

The visit questionnaire provided space to record up to four diagnoses/problems. In each case GPs were asked to record actions taken and treatments given. During data entry the GP’s text was recorded in full. Data on drug treatments have been presented above; here data on “other treatments” and “actions” are reported. They were coded on the basis of individual words, although these actions sometimes overlapped (e.g. “school letter” would code twice to “administration”). Only one action of each type (e.g. administration) could be counted for each problem.

Table 36 gives the frequency of non-drug treatments and actions. Health advice was not only given but also recorded at a rate of 38.5 per 100 visits. Investigation, examination and screening was the second most common type of action recorded (29). Referral and follow-up were recorded at 16 and 6.9 per 100 visits, respectively. Minor surgery was relatively common (6.6), as were administrative activities (5.7). “Other procedures” (3.8) and dressings (3.1) were less common. Immunisation and complementary medicine occurred in 2.1 and 1.7 per 100 visits, respectively.

Data on referral and follow-up were specifically requested elsewhere on the visit questionnaire. Data values are virtually identical for referral, which is undoubtedly an action. Follow-up, which might well not be considered to be an action, was under- reported here.

Table 36: Frequency of non-drug treatments Non-drug treatments Percentage of all Frequency Frequency per 100 treatments per 100 visits problems

Health advice 33.7 38.5 23 Investigation/examination/screening 25.4 29 17.3 Referral 14 16 9.6 Follow-up 6.1 6.9 4.1 Minor surgery 5.8 6.6 4 Administration 5 5.7 3.4 Other procedures 3.3 3.8 2.3 Dressing 2.7 3.1 1.9 Immunisation 1.9 2.1 1.3 Complementary medicine 1.5 1.7 1 Physical medicine 0.6 0.7 0.4 Total 100%

Referral occurred most commonly in the 15-44 years age band, suggesting an association with injury and (possibly) pregnancy rather than with illness (Table 37). Table 37: Referral: age- and gender-specific rates (per 100 visits)

All ages < 1 01-04 05-14 15 24 25 34 35 44 45 54 55 64 65 74 75+

Male 15 9 6 10 15 20 21 11 17 19 20 Female 16 9 5 9 14 22 24 20 16 16 14

Elective referral to medical and surgical services increased with age, with peaks at 35- 44 and 65-74 years for men, and at 35-44 years for women (Table 38).

Table 38: Elective medical/surgical referral: age and gender-specific rates (per 100 visits)

All ages < 1 01-04 05-14 1524 2534 3544 4554 5564 6574 75+

Male 8 4 2 5 7 7 13 6 11 12 9 Female 8 3 3 4 6 10 13 10 7 9 8

Among elective referrals, patients with congenital, genito-urinary and neoplasmic and musculoskeletal conditions were referred on in at least 14% of cases. Infectious, respiratory and perinatal problems were referred on in less than 6% of cases (Table 39).

Table 39: Rates of elective referral, by problem grouping Problem grouping (based on READ2 chapters) Percent of problems so Percent of new treated problems so treated Congenital 22 43.6 Genito-urinary 19.3 14.9 Cancers/neoplasms 17.5 16.2 Musculoskeletal / connective tissue 14.2 11 Pregnancy/childbirth/puerperium 13 3.4 Digestive 12.4 11.1 Unspecified conditions 12.4 8.8 Mental 12 14 Symptoms non-specific 11.7 4.9 Blood / blood-forming organs 11.6 0 Cardiovascular/circulatory 10.7 14 Nervous system / sense organs 10.6 8.7 Endocrine/nutritional/metabolic/immunity 10.3 18.1 Investigations 9.1 8.3 Actions 7.2 10 Injury/poisoning 6.6 5.5 Skin / subcutaneous tissue 6.5 4.2 Infectious/parasitic 5.2 2.2 Respiratory 3.8 2.7 Perinatal 0 0 Not coded 18.7 31.8

Rates of emergency referral were fairly consistent across the life course, with a peak in the first year of life and after age 75 (although this was less marked for women) (Table 40).

Table 40: Emergency referral: age- and gender-specific rates (per 100 visits)

All ages < 1 01-Apr May-14 1524 2534 3544 4554 5564 6574 75+

Male 1.4 3.4 1.1 1 1.3 0.5 0.5 0.9 1.3 1.2 3.7 Female 1.3 3.8 0.2 1.8 1.4 1.4 0.6 1.4 1.8 1.1 1.2

Among emergency referrals, only pregnant patients had a high rate of emergency referral (18.4%) (Table 41). Table 41: Rates of emergency referral, by problem grouping

Problem grouping (based on READ2 chapters) Percent of problems so Percent of new treated problems so treated Pregnancy/childbirth/puerperium 18.4 12.5 Cardiovascular/circulatory 2.3 6.3 Genito-urinary 2 3.9 Respiratory 1.4 1.3 Endocrine/nutritional/metabolic/immunity 1.4 11.8 Injury/poisoning 1.3 2 Skin / subcutaneous tissue 1.3 0.9 Digestive 1.1 1 Symptoms non-specific 1 1.3 Nervous system / sense organs 1 1.2 Infectious/parasitic 1 1.1 Musculoskeletal / connective tissue 0.7 1.1 Actions 0.7 0 Mental 0.6 0 Cancers/neoplasms 0.6 1.6 Unspecified conditions 0.6 0 Investigations 0.4 0.9 Blood / blood-forming organs 0 0 Congenital 0 0 Perinatal 0 0 Not coded 0 0 Patients with injuries (15.4%), musculoskeletal (15.2%) and mental (11.1%) problems had the highest rates of non-medical referral (Table 42).

Non-medical referral occurred in 5% of visits. A peak for men in the 15-34 band suggests a relationship with sport and work-related injury. For women the peak occurs later. Table 42: Rates of non-medical referral by problem grouping

Problem grouping (based on READ2 chapters) Percent of problems so Percent of new treated problems so treated Injury/poisoning 15.4 18.5 Musculoskeletal / connective tissue 15.2 21.8 Mental 11.1 16.7 Actions 8.2 7.7 Investigations 7.9 11.7 Endocrine/nutritional/metabolic/immunity 7 8.1 Congenital 6.9 35.1 Symptoms non-specific 6.7 9.1 Genito-urinary 6.5 8.2 Digestive 5.9 5.6 Unspecified conditions 5.7 8.2 Nervous system / sense organs 4.8 5 Pregnancy/childbirth/puerperium 4.5 5.9 Cancers/neoplasms 4.2 5.1 Blood / blood-forming organs 3.9 0 Skin / subcutaneous tissue 3.9 3.7 Cardiovascular/circulatory 3.4 7.3 Respiratory 2 2 Infectious/parasitic 1.6 1.6 Perinatal 0 0 Not coded 7.6 15.6

Table 43 shows the destination of the referrals. Of all visits, 1.3% ended in a referral to the emergency department, 8% in a referral to a medical or surgical specialist, and 5.7% in a non-medical referral. The commonest specialties cited were orthopaedics and physiotherapy.

Table 43: Destination of referrals: percentage distribution and frequency per 100 visits

Destination Percentage of referrals Frequency per 100 visits Emergency referral 8.2 1.3 Referral unspecified 5.1 0.8 Medical/surgical specialties 50.6 8 Orthopaedics 7.1 1.11 ENT 4.8 0.75 Cardiology 3.8 0.6 Gynaecology 3.5 0.55 Gastroenterology 2.9 0.45 Urology 2.8 0.43 Ophthalmology 2.4 0.38 Paediatrics 2.4 0.38 Psychiatry 2.1 0.33 Dermatology 1.7 0.27 Neurology 1.7 0.27 Rheumatology 1.6 0.25 Plastic surgery 1.4 0.22 Obstetric 1.2 0.19 Non-medical referrals 36.1 5.7 Physiotherapist 11.5 1.8 Radiology 8.9 1.4 Nursing 2.2 0.35 Counselling 2.2 0.34 Midwife 1.4 0.22 Dental 1 0.15 Audiology 1 0.15 Total 100% 15.8 7. Patient satisfaction:

7.1 Satisfaction with general practitioner services

Overall, almost all adults said they have been very satisfied (48.4%; 46.9–49.9) or satisfied (44.8%; 43.2–46.3) with their last GP visit. When adults who were dissatisfied with their last GP visit were asked why, the most common reasons were:

“costs too much” (40.2%; 34.7–45.6)

“ doctor did not spend enough time or wasn’t thorough enough” (40.0%; 34.6– 45.3)

“ doctor gave wrong treatment or didn’t give any treatment or only prescribed drugs” (22.5%; 17.4–27.5)

“didn’t like doctor’s manner or couldn’t talk to doctor or doctor wouldn’t listen” (21.0%; 16.8–25.2). Source: Auckland City Council Survey Overall, the main reasons given by Maori adults for choosing a Maori health provider were:

“I feel more comfortable talking to someone who understands my culture” (34.5%; 25.9–43.1)

“it was cheaper than going to another provider” (27.3%; 21.2–33.4)

“I was referred to them by a friend or relative” (25.9%; 19.3–32.5)

“ they are interested in the impact that my health and its treatments has on my whānau or family” (25.5%; 17.5–33.4)

“I find they are willing to spend more time discussing my health” (18.3%; 12.6– 24.1)

“they were the closest provider” (14.9%; 10.0–19.7)

“they offer specialist services that I need” (11.6%; 7.2–16.1)

“I was referred to them by my doctor” (10.0%; 5.8–14.1).

Among Maori adults who had seen a Maori health provider about their health in the last 12 months, almost all were very satisfied (55.3%; 46.9–63.6) or satisfied (36.9%; 31.8–47.3) with the consultation. The most common reason for any dissatisfaction with a Maori health provider was that the doctor did not spend enough time or was not thorough enough.

Overall, almost all Pacific adults who saw a Pacific health provider about their health were very satisfied (43.6%; 25.8–61.3) or satisfied (55.5%; 37.8–73.3) with the consultation. Of the few Pacific adults dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with the consultation, the reasons given were: “costs too much” “didn’t like doctor or couldn’t talk to doctor or doctor wouldn’t listen”.