Pat Schuler, Ph.D., NCC, LMNC Creative Insights 257-2018 [email protected] Greenmeadow Park 1654 Columbia Turnpike Castleton-on-Hudson, NY 12033 1 Social-Emotional Needs/Issues of Gifted Children

• Gifted children have cognitive/academic needs, personal-social needs, and experiential needs •

Only a small proportion of gifted children have psychological adjustment problems, so why is it important to address their social and emotional needs? • our culture is ambivalent about giftedness • gifted and talented children do not automatically realize their potential abilities • lack of validation may result in negative self-image, low self-esteem • too much pressure, overcommitment, loneliness, dependence on external motivation, extreme competitiveness, and other stressors may result in depression • alienation, humiliation, isolation, or depression when experienced with intensity can be fatal • some gifted are at risk for: underachievement, dysfunctional perfectionism, eating disorders, school drop-out, depression, suicide • the more highly gifted- the more vulnerable to problems • the possible strain on family dynamics

Giftedness Affects Psychological Well-Being and Development (Neihart, 1998) • Goal of Classroom Teacher: support positive social and emotional growth of students • Objectives to do so for gifted students: 1. Teacher accepts that gifted children are different from other children in some ways. 2. Teacher has a basic understanding of how giftedness affects development and psychological well-being. 3. Teacher has practical strategies for supporting the student in the regular classroom. Three Factors: 1. Particular way person is gifted 2. Degree of giftedness 3. How well a gifted person's needs are being met

Overexcitabilities (Dabrowski) 1. Psychomotor (e.g., fast games and sports, acting out, impulsive actions) 2. Intellectual (e.g., introspection, avid reading, curiosity) 3. Imagination (e.g., fantasy, animistic and magical thinking, mixing truth and fiction, illusions) 4. Emotional (e.g., strong affective memory, concern with death, depressive and suicidal moods, sensitivity in relationships, feelings of inadequacy and inferiority) 5. Sensual (e.g., sensory pleasure)

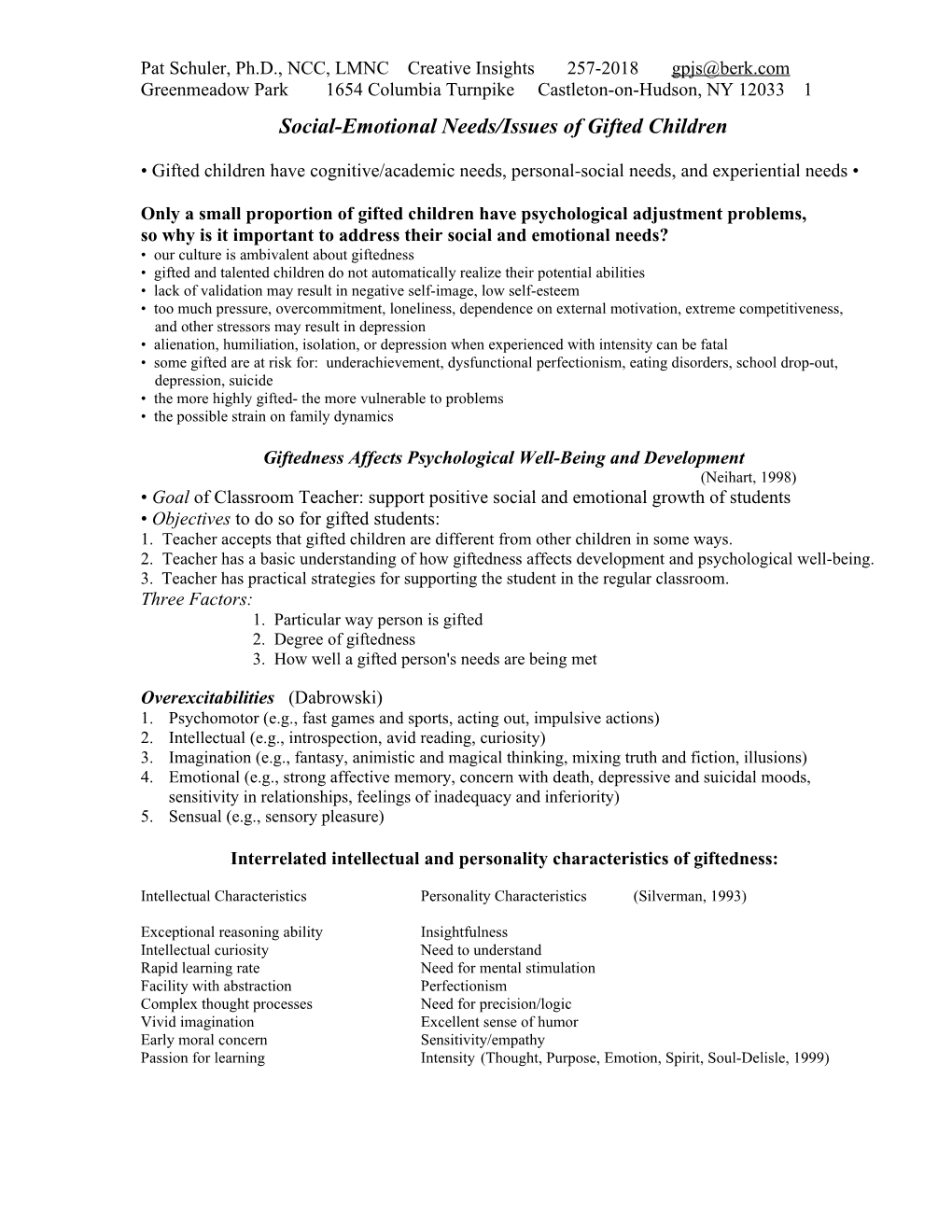

Interrelated intellectual and personality characteristics of giftedness:

Intellectual Characteristics Personality Characteristics (Silverman, 1993)

Exceptional reasoning ability Insightfulness Intellectual curiosity Need to understand Rapid learning rate Need for mental stimulation Facility with abstraction Perfectionism Complex thought processes Need for precision/logic Vivid imagination Excellent sense of humor Early moral concern Sensitivity/empathy Passion for learning Intensity (Thought, Purpose, Emotion, Spirit, Soul-Delisle, 1999) Pat Schuler, Ph.D., NCC, LMNC Creative Insights 257-2018 [email protected] Greenmeadow Park 1654 Columbia Turnpike Castleton-on-Hudson, NY 12033 2 Accelerated and Enriched Learners “… qualitatively different needs and learning styles of gifted youngsters and not simply methods of how to provide for those needs.” (Colangelo and Zaffran in Schmitz & Galbraith, 1988)

Accelerated • interested in mastering & integrating increasingly complex material • ability to learn fast • recall large amounts of information fast • highly efficient information-processors • crave new information, harder problems • sense of fulfillment: mastering higher & higher levels of material & applying it to solve problems of increasing difficulty • high achievers in well-defined discipline • succeed in curricular systems-stress knowledge acquisition, linear skill building, logical analysis • may be indifferent to academic subject areas • sources of stress: lock-step learning, endless drill & practice, fear of failure, socially immature • need: help setting realistic goals, social skills Enriched • wholly involved or immersed in a problem- forms a “relationship” with a problem • focus on the problem as an end in itself rather than as a means to obtain more knowledge • their relationship to problem • and the learning process • highly emotional, imaginative, internally motivated, curious, driven to explore • reflective and emotionally mature • passionate about a subject, project, cause • aren’t especially concerned with achievement • invest great deal of emotional energy • require teachers who are sensitive to intensity • feelings: frustration, passion, enthusiasm, idealism, anger, despair • need: adult support to persist and/or harness energies more efficiently

Specific problems that may result can be external or internal -- Difficulty with social relationships -- Refusal to do routine, repetitive assignments -- Inappropriate criticism of others -- Lack of awareness of impact on others -- Lack of sufficient challenge in schoolwork -- Depression (often manifested in boredom) -- High levels of anxiety -- Difficulty accepting criticism -- Hiding talents to fit with peers -- Nonconformity and resistance to authority -- Excessive competitiveness -- Isolation from peers -- Low frustration tolerance -- Poor study habits -- Difficulty in selecting among a diversity of interests (Silverman, 1987)

External Barriers for Cognitive/Affective Growth of Gifted Students (Nevitt, 1999; Roberts, 2001) 1) Low expectations-parents, family members; teachers; stereotypic beliefs and myths 2) Grouping by age 3) Policy-national, state, local (one-size fits all; fear of causing arrogance?) 4) Lack of understanding of social/emotional/cognitive needs • family conditions: perceived lack of support and nurturance; family problems

“Top Criticisms” Aimed at Gifted People (Jacobsen, The Gifted Adult, 1999) • Who do you think you are? • Where do you get those wild ideas? • You’re so driven! • Can’t you ever be satisfied? • You’re so demanding! • You have to do everything the hard way. • You’re so sensitive and dramatic! • Can’t you just stick with one thing? • You worry about everything! • Why don’t you slow down? Pat Schuler, Ph.D., NCC, LMNC Creative Insights 257-2018 [email protected] Greenmeadow Park 1654 Columbia Turnpike Castleton-on-Hudson, NY 12033 3

Eight Great Gripes of Gifted Children (Schmitz & Galbraith, 1985) 1. No one explains what being gifted is all about-it's kept a big secret. 2. School is too easy and too boring. 3. Parents, teachers, and friends expect us to be perfect all the time. 4. Friends who really understand us are few and far between. 5. Kids often tease us about being smart. 6. We feel overwhelmed by the number of things we can do in life. 7. We feel different, alienated. 8. We worry about world problems and feel helpless to do anything about them. (Dirkes, 1983)

Stress

• The effect of any one stressor is exacerbated if it is accompanied by other stressors. • Adolescents who have other resources-either internal (high self-esteem, healthy identity development, strong feelings of competence) or external (social support from others) are less likely to be adversely affected by stress than their peers. • Adolescents who have warm and close family relationships are less likely to be distressed by stressful situations than those without familial support. • Presence of a close parent-adolescent relationship-probably single most important factor in protecting adolescents from harm. (in Steinberg, Adolescence)

Stress Experienced by Gifted People • easy learning conditions them to effortless existence • expectations- higher, “should know better” • shame and abandonment- should succeed without help • generalizations- high performance in all areas • differences from peers- frightening and alienating • cope with more possibilities, more meanings • hypersensitivities-trouble screening out; view as less able to cope • deal with more alternatives-potential for more mistakes • more curious, more questions, process slower- less smart • frustration-want to actualize greater number of options • personalize situations-feel more responsible • waiting –boredom (toxic to brain, low grade “mad”) • aware of others’ incongruities-confusion how to respond • more conscious of whole situation-more ambiguity • perfectionistic- feel valued by their accomplishments

Stress Experienced by Highly Gifted People • enormous capacity for consciousness- intensity • highly sensitive-deep, emotional responses • curious, process more information • learn easily-expect less effort • abilities are generalized-higher expectations • tension with peers-differences in abilities, emotions, realities • vivid imagination-pursue more possibilities • compromise ideals-resources and time limitations • confused on how to respond to others’ incongruencies • more conscious of whole situation-complexity, multiple solutions; paradoxical ideas & situations • perfectionistic tendencies Pat Schuler, Ph.D., NCC, LMNC Creative Insights 257-2018 [email protected] Greenmeadow Park 1654 Columbia Turnpike Castleton-on-Hudson, NY 12033 4 • hesitate to ask for help: “should know better” • feelings of shame and abandonment • personalize situations-feel responsible

Stress Experienced by Families of Highly Gifted Children • experiences contradict or challenge what we think about gifted kids • lack of established body of expertise for guidance • perceptions often disqualified • lack of experience and expertise in program options • severely isolated from ordinary support systems • anger at community and at child • conflicting expertise + personal wisdom + road blocks = feeling of too few options • beleaguered by critical, unsympathetic appraisal - blame • more energy and involvement needed = depletion • financial burden = resentment • hopelessness and helplessness (E. Meckstroth)

Symptoms of undesirable levels of anxiety in gifted children:

-- decreased performance -- expressed desire to be like teen-agers -- reluctance to work in a team -- expressions of low self-concept -- excessive sadness or rebellion -- reluctance to make choices or suggestions -- extremes of activity or inactivity -- a change in noise or quietude -- repetition of rules and directions to make sure that they can be followed -- avoidance of new ventures unless certain of the outcome -- other marked changes in personality

Stress Management and Gifted Children

Understanding Stress and Stressors 1. Stress can be good. 2. Excessive stress can cause problems. 3. Physical responses to stress include accelerated heartbeat, cold extremities, tight muscles, tense shoulders, a “pressure” headache, dry mouth, clammy hands, and/or stomach or intestinal disorders. 4. Prolonged periods of stress can lead to significant physical problems. 5. Most people seem to be vulnerable to excessive stress in a particular way. 6. Stress can develop from having to do “something different”. • Describe your own physical and emotional responses to stress: • What tells you that you are under stress? • How do you behave? • How do you feel? • How does your body react? • Questions to consider: • Do you feel stress from competition (academic, athletic, arts, etc.)? • Do you feel as if you are ahead intellectually but behind socially? • Do you feel great pressure to achieve? From others? From yourself? • Do you work slowly? • Is needing/trying to please everyone a problem for you? Peterson, J. S. (1993). Talk With Teens About Self and Stress. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit. Pat Schuler, Ph.D., NCC, LMNC Creative Insights 257-2018 [email protected] Greenmeadow Park 1654 Columbia Turnpike Castleton-on-Hudson, NY 12033 5

Strategies • Encourage "one-thing-at-a-time" thinking. • Practice muscle relaxation. • Practice deep breathing. • Remember good old-fashioned exercise! • Encourage a stress-reducing diet. • Allow the "space" for daydreaming. • Respect your child's heightened sensitivities. • Be a role model.

Alvino, J. (1995). Considerations and strategies for parenting the gifted child. Storrs, CT: The National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented.

Approach: Importance of helping gifted children develop an awareness of their own personal priorities and values. (Webb, Meckstroth, & Tolain. Guiding the Gifted Child)

• Covering up problems usually creates stress; talking about them generally helps. • "What is the worst things that could happen in that situation?" • "You feel you should ... but it sounds as if that is not what you want."

• Teach children tools for making decisions. • Creative problem solving process • SCAMPER: S... Substitute (What similarities exist; what could be substituted?) C... Combine (Might something be combined or brought together?) A... Adjust (What changes or adjustments could be made to help?) M... Magnify, Minify, Modify (What could happen in these conditions?) P... Put to other uses (In what other ways might parts be used?) E... Eliminate, Elaborate (What could be removed or enhanced?) R... Reverse, Rearrange (What effects would come from changing the sequence?) • Teach them to set short-term, intermediate objectives, as well as long-term goals. • Help them reward themselves for their attempts at success as well as for achieving success. • One specific goal should always be to "try again." • Blaming others is not helpful for reducing stress. • Teach them that a problem situation can work for them, rather than against them. • Perhaps there are ways of using the situation to achieve some goal that is not immediately apparent. • Even in problem situations, she has choices. • Compartmentalized thinking can be developed. • Immediate calming techniques are helpful. • Counting to ten, vigorous physical exercise, meditation or conscious concentration on controlling breathing, physically relaxing parts of your body • HALT (Hungry, Angry, Lonely, Tired): a warning signal to slow down and to watch for stress effects • Sleep • Tension situations can be handled with humor. • The gifted child can control tense situations by expressing appreciation & understanding for others who are upset or critical of him. • Cope with stressful situations through "active ignoring." • Learn to question "Whose problem is it?" • "Just because they say something about me doesn't make it so. I'll decide if I think it is accurate. Then I will decide what, if anything, I want to do about it."

Coping Strategies (Steinberg) Problem-focused coping: taking steps to change source of stress • active mastery of the stressor (treatment of the problem) Emotion-focused coping: efforts to change one’s emotional response to the stress • passive avoidance or distraction (treatment of the symptom) Pat Schuler, Ph.D., NCC, LMNC Creative Insights 257-2018 [email protected] Greenmeadow Park 1654 Columbia Turnpike Castleton-on-Hudson, NY 12033 6 Seven Strategies for Stress Management 1. Help your children to identify their values, hopes, and dreams so that they live a life consistent with their values and goals. 2. Create opportunities to identify and explore the issues with your children. 3. Use family meetings to discuss issues. 4. Establish weekly “walk and talks.” 5. Create balance in your life. 6. Encourage your children to have a creative outlet. 7. Teach and model the use of stress busters. • Deep breathing • Disassociation (visualization) • Finding someone to talk to • Neck rolls Nichols, H. J. & Baum, S. (December 2000). High achievers actively engaged but secretly stressed: Keys to helping youngsters with stress reduction. Parenting for High Potential.

Anger: Responses by Gifted Children (Ellen Fiedler, 1998) • Intellectualize • Bury anger under apparently calm façade • Reject acknowledgement of/expression of anger- desire to be non-judgmental, open-minded, positive, and accepting of others • Blow up with hurricane-force intensity at a moment’s notice • Inwardly wrestle with underlying beliefs that anger is uncontrollable, dangerous, & primarily destructive • Being acutely aware of pain that others feel as the result of being the target of anyone’s anger • Some or all of above • Other? Strategies to help gifted children cope with their anger General: • Techniques-greater self-understanding and acceptance • Be available, accepting, and LISTEN • Guide them in identifying when they are angry, how that feels for them, and what helps them, specifically to work their way through it • Be authentic about your own experience with anger; model ways of coping that honor your Self • Provide multiple opportunities for them to interact in a psychologically safe environment with others who are like them • Develop effective communication & collaboration between parents & teachers Specific: • Journaling/tape recording • Creative expression of all sorts • Guided group work with other gifted kids • Bibliotherapy • Literature studies and Junior Great Books • Self-help books for kids • Biography studies • Mentorships • Social action, service learning • “Centering” techniques • Permission for self-selected time out-“as needed” basis

Bright Kids and the Attraction to Violent Games Reasons for the Attraction: • Provides the intellectual challenge they crave • Able to use their creativity in problem solving • Able to use their vivid imaginations through the fantasy • Opportunity to socialize with comparable peers • Able to use their learning style: visual, spatial, global, bodily-kinesthetic • Opportunity to release stress from being “different” and/or teased/bullied (Schuler, 1999) Pat Schuler, Ph.D., NCC, LMNC Creative Insights 257-2018 [email protected] Greenmeadow Park 1654 Columbia Turnpike Castleton-on-Hudson, NY 12033 7

Medical Conditions Masked by Anxiety Hyperthyroidism = Hypothyroidism = (Thyrotoxicosis) (Myxedema) All anxiety symptoms except cold sweats Anxiety with irritability Clients are “hot” to the touch Lethargy Occasional hyperactive or grandiose behavior Thought disorder Increased appetite & intake, but losing weight Somatic delusion Hair is fine Hallucinations Eyeballs protrude Puffy face Constantly anxious (not attacks) Dry skin Weight loss of ten pounds in a year Cold intolerance Loss of strength Heat intolerance

Hypo-Parathyroidism = Kidney Disease = Anxiety, hyperactivity Anxious, depressed, irritable Irritability Hyperventilation Confusion, disorientation Parathesias (numbness and tingling Clouded sensorium of the extremities) Rarely produces aberrant behavior Chronically nauseous Constantly constipated Parathesias does not abate when hyperventilation ends

Tuberculosis = Heart Disease = All anxiety symptoms Anxiety, depression Night sweats Hyperventilation with parethesias Chronic Fatigue If paresthesias does not disappear or abate after Recent weight loss hyperventilating or anxiety, refer to physician Alcoholism prevalent for possible heart and/or kidney problems Such symptoms with profuse sweating and chest Pheochromocytoma = pain could be a heart attack in progress and (Extremely Rare Adrenal Tumor) medical treatment immediately Fear and dread Short bouts of anxiety daily Panic Hypoglycemia = Apprehension Anxiety Persistent headaches Fear and dread Sweating during elevated blood pressure Depression with fatigue Trembling Sugar relieves symptoms in 10seconds to 1/2 hour Strange smells before anxiety attacks Anxiety medicines will not alter true hypoglycemia Blurred vision or other problems with eyesight Symptoms are prevalent before breakfast Confusion during anxiety attacks Dramatic mood lability Pat Schuler, Ph.D., NCC, LMNC Creative Insights 257-2018 [email protected] Greenmeadow Park 1654 Columbia Turnpike Castleton-on-Hudson, NY 12033 8 Strategies for Addressing Social/Emotional Problems of Gifted Students (Neavitt, 1999; NAGC National Conference) • Educating teachers regarding: • true characteristics and needs of gifted students • appropriate expectations • differentiated curriculum • appropriate educational environment • acknowledging and addressing individual needs in the classroom • Educating parents, when children are identified, regarding: • characteristics and needs • appropriate expectations • importance of valuing the child as a person, not just for “gifted performance” • recognizing that problems, between parents, or within family, need to be addressed, not ignored (A bright perceptive child will be more aware of, and disturbed by, problems than most parents realize.) • Incorporating affective components into the curriculum • what it means to be gifted • respect for individual differences • understanding self and others • relationships with others • Counseling, if needed • school counseling may not be enough • family counseling may be most productive, even without school counseling • counselors who work with gifted students should have knowledge and skills to address the social/emotional needs of these students • Incorporating a multiple component approach to problems which seriously affect school performance, utilizing a cooperative plan involving the student, home, and school

Cognitive/Academic Needs: Removing the Learning Ceiling (J. Roberts, Keynote Address, Kentucky AGATE, 2/22/01) Strategies to Lift the Learning Ceiling: • Continuous progress (level and pace appropriate) • Cluster grouping (vs. “sprinkling”) • Grouping for instruction (achievement occurs when instruction matches readiness) • Thinking and Problem Solving • Pre-assessment (document of need) • Differentiation (modifications that are specific) • Different categories of giftedness (academic, creativity, leadership, visual/performing arts) • Multiple delivery systems • Individual Education Plan • Challenge requiring hard work

Suggestions for Educators, Parents, Counselors (Cross, 1998-Working on Behalf of Gifted Students, Gifted Child Today)

1. Encourage controlled risk-taking (build same and opposite sex relationships & communicate with other students & teachers). • safeguards: accepting environment, supportive school climate 2. Provide myriad social experiences for gifted students. 3. Inventory family similarities and differences as compared to schoolmates. • within context of diversity, giftedness can be accepted as normal, rather than aberrant Pat Schuler, Ph.D., NCC, LMNC Creative Insights 257-2018 [email protected] Greenmeadow Park 1654 Columbia Turnpike Castleton-on-Hudson, NY 12033 9 4. Encourage reading of biographies of eminent people (form of bibliotherapy). • opportunities to understand how experiences impact one’s development • similar struggles reduces feelings of isolation & provides options for dealing with difficulties 5. Provide mentorship opportunities for gifted students. • opportunities to learn about individual pathways 6. Love and respect gifted students for who they are. • emphasis how one develops one’s abilities and talents that make them virtuous • encourage avocation talent to avoid identity foreclosure 7. Encourage a self-concept that extends far beyond the academic self-concept. • understand gifted children develop over time and deserve the right to develop various aspect of their being

Resiliency Research

Protective Factors: 3 Categories (Benard, 1996)

• Caring and supportive relationships • Positive and high expectations • Opportunities for meaningful participation

• Caring and supportive relationships

• make family involvement in schooling a priority through actively recruiting parents • establish meaningful roles in the schools for parents and children • contact parents periodically to share some good news about their children

• Positive and High Expectations

• acknowledge strengths and assets as opposed to problems and deficits • set and communicate high expectations by letting students know that they are capable and that it matters that they can do well • develop growth plans, celebrate success and talent • make curriculum adjustments to accommodate students’ individual profiles • provide security of what is expected and communicate it on a regular basis (Benard, 1996; Henderson & Milstein, 1996)

• Opportunities for Meaningful Participation

Important for students and families to:

• believe that they are doing things that matter • be challenged to contribute to their fullest capacity • recognize the value of participating • have a sense of the impact of the overall organizational dynamics on their own futures • feel free to probe assumptions • be encouraged to experiment and take risks (Henderson & Milstein, 1996) Pat Schuler, Ph.D., NCC, LMNC Creative Insights 257-2018 [email protected] Greenmeadow Park 1654 Columbia Turnpike Castleton-on-Hudson, NY 12033 10

Strategies that Work! • peer support groups • altered school structure • group counseling • bibliotherapy • cinematherapy • moral exemplars • moral exemplars • mentorships • internships • peer counseling • family counseling

Coping skills Use Creative Decision-Making • Try it out in your mind 1. Define the problem • Use positive self-talk 2. Find the facts • Change the channel 3. Brainstorm ideas • Read about it 4. Consider the best ideas 5. Make a plan 6. Review how the plan has worked 7. Try again

Smutny, Meckstroth, Walker (1997). Teaching young gifted children in the regular classroom. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit.

Strategies used at Creative Insights

• Degree of Intensity, Discomfort, Pleasure, Challenge, etc. (1-5) • How would you represent your level of feeling using a scale of 1 through 5 (1- 5) with 1 representing very little intensity, discomfort, pleasure, challenge, etc., to 5 representing almost unbearable intensity, discomfort, or the greatest pleasure or positive challenge?

• “Who Am I?” • Review intellectual and personality characteristics of giftedness

• “Build” yourself • Using Legos ™ the student will “create” themselves-strengths and limitations. What do the pieces, colors, design, etc. symbolize?

• Venn Diagrams • How are you similar and different to others (peers, family, friends, etc.) in interests, abilities, strengths, limitations, etc. • Use Inspiration software to create graphic organizers

• Strengths/ Limitations

• Collections • Student creates exhibit of his/her collectibles • How does this collection help to define a “puzzle piece” -strengths, interests, learning style, etc.

• Great Goof-Ups • Great Goof-Ups is a multidimensional tool to de-emphasize unhealthy perfectionism in and out of the classroom • Encourages self-acceptance, risk-taking, and acceptance of others. Helps to create a safe environment in which it is permissible to be imperfect. • Exercise is a 5 to 20 minute activity which can be used on a daily or weekly basis. • To order instructional manual, send a check or money order for $15 to: Sharon Lind 12302 South East 237th Place Kent, Washington 98031 Pat Schuler, Ph.D., NCC, LMNC Creative Insights 257-2018 [email protected] Greenmeadow Park 1654 Columbia Turnpike Castleton-on-Hudson, NY 12033 11

• “What’s On Your Plate?” • In a graphic way, show all the things/activities/responsibilities that are happening in your life • Designate which ones take up the most time • Designate which ones are most/least stressful • Variation: on the back, show in a graphic way your “ideal” world-what activities/responsibilities would give you enjoyment/pleasure • Variation: on the back, show in a graphic way how you deal with stress of all the things on your plate

• “Perfect Day” • Describe your ideal day-at school, at home, a trip, etc. • What does it look like? Who will be with you? What will you do? How will it end?

• Goal Sheet: Area Goal + / - Strategies • Academic • Physical • Social • Emotional • Spiritual • Other • Understanding Anxiety • Research and discuss what anxiety is and how it impacts mind, body, spirit

• Positive Self-Talk (We become what we tell ourselves we are.) • mental images we send ourselves before, during, and after events • gives us advice, assesses our progress, evaluates our performance, suggests future actions and explanations • can be positive or negative • connect self-talk to choice of coping strategies • Modeling (audio tapes of appropriate scripts, visualization, peer coaching, oral reflection, oral metacognition, practice) • What you take away must be replaced by other mental messages • What is your daily litany? How do you begin your day? What do you say to your peers about your abilities or beliefs? (adapted from Burrus, 2001)

• Principles for Class Success • Discuss their perceptions of the Principles • How to implement the Principles while still being true to themselves

• Self-Evaluation • Evaluate intellectual challenge of work: GMM (Give Me More), TC (Too Challenging) WTE (Way Too Easy), WTH (Way Too Hard)

• Nutrition • Provide opportunities for research, discussion, meeting with nutritionist about specific issues (Ex., allergies)

• Imagery • Relaxation exercises • Relax your feet

• Stress Boxes Pat Schuler, Ph.D., NCC, LMNC Creative Insights 257-2018 [email protected] Greenmeadow Park 1654 Columbia Turnpike Castleton-on-Hudson, NY 12033 12 • Checklist of Symptoms of Student Burnout • My Needs, My Wish List

• Student Needs Assessment

• Weekly Evaluation Sheet

• Adolescent Coping Strategies

• Gifted Kids with Individuals with Disabilities • Provide opportunities for research, discussion, meeting with gifted individuals who have disabilities

Depression and Gifted Children/Adolescents

Sadness and Depression

• Sadness- universal emotion; conflict-free emotion where we are aware of what sometimes feels like inescapable pain at a sense of loss or disappointment which can usually be explained by the circumstances.

• Depression- refers to intense feelings of despair, guilt, hopelessness, and a sense of worthlessness. A depressed person recognizes that things are not as they should be, but feels helpless to correct the situation. • a cognitive-affective disorder: related to the thoughts & feelings that individuals have about themselves & their circumstances • cognitive-affective changes • result in lowered self-esteem, distortions of perceptions, & a devaluation of self • accompanied by feelings of helplessness & hopelessness • a state of being pressed down; a notion of conflict; aggression against self or others • "anger" with no place to go

Possible Causes • result from too much pressure, over-commitment, loneliness, dependence on extrinsic motivation, extreme competitiveness, & other stressors • physical causes: low thyroid condition, hypoglycemia, anemia, drug reactions, changes in endocrine system

Three kinds of depression associated with gifted children/adolescents: • perfectionism: desire to live up to standards of morality, responsibility & achievement they may have set impossibly high • alienation: feeling cut off from other people • existential: intense concerns about the basic problems of human existence; personal worry about the meaning of the child's own life

Existential Depression • their capacity for absorbing information about disturbing events is greater than their capacity to process and understand it • can result from not only their advanced reading ability but also from their participation in activities that call for greater maturity Pat Schuler, Ph.D., NCC, LMNC Creative Insights 257-2018 [email protected] Greenmeadow Park 1654 Columbia Turnpike Castleton-on-Hudson, NY 12033 13 • result of trying to understand: meaning of life, inevitability of death, & the beginning & end of the universe • results from incongruence between the child's developmental stage & intellectual abilities • cognitive development may still be "dualistic" (sees world in terms of absolutes such as right and wrong or good and bad) • pervasive sense of loneliness, accompanied by depression & anger

• to cope with it- find meaning in their own lives & in their relation to others • must develop a sense of belonging in the universe

Suggestions • Do not pass off a child's depression as a "stage," or tell child to "just snap out of it." • Do not try to argue a child out of depression. • Adopt a posture of "I'm sorry you feel that way," instead of trying to reason the child out of her/his depression. • Helpful technique- bibliotherapy • Speak with school counselor/psychologist/administrator in order to get family involved with treatment. • Teachers-do not take on the role of therapist • School mental health professionals and administrators: know when to refer to outside professionals • locate professional who has experience and training in working with gifted kids

Grief and Mourning • allow and encourage the expression of grief • responses to grief- show feelings by withdrawal or changes in eating or sleeping patterns • talk and listen: tell them what is happening- and as far as possible-why

Suicide and Gifted Children/Adolescents

• gifted students may be particularly at risk • unusual sensitivity to perfectionism • isolationism related to extreme introversion • overexcitabilities (Dabrowski) • heightened sensitivity and awareness-particularly when there is instability, trauma, and lack of control • result of the intensity and duration of psychological & situational problems they have been experiencing • die more often • more effective planners of their own suicide • may engage in more deception & may be much more careful in their planning • characteristics that can make them vulnerable to suicide: • non-productive coping strategies • deficit social skills or social isolation • unhealthy: unrealistic expectations

Additional factors/behaviors for suicide potential for gifted: • self-imposed perfection as the ultimate standard, to the point that the only tasks enjoyed are the ones completed perfectly • distorted perceptions of failure; fear of making mistakes; self-doubt • socially prescribed perfectionism Pat Schuler, Ph.D., NCC, LMNC Creative Insights 257-2018 [email protected] Greenmeadow Park 1654 Columbia Turnpike Castleton-on-Hudson, NY 12033 14 • developmental dysplasias (gaps between social, emotional, or physical & cognitive abilities) • success depression • conflict between trying to please parents by doing well & fitting in with peers by not doing well • deep concern with personal powerlessness to affect adult situations &world events • inappropriate educational settings • loneliness; alienation from others • narcissism- total preoccupation with self & with fantasy • unusual fascination with violence • eating disorders • rigidly compulsive behaviors • previous attempt(s) which can be in the form of any self-inflicted injury • suicidal behavior- comes from repeated stressful situations with which she/he feels unable to cope • anger within depression grows so great- punished herself/himself or some else in the most dramatic way possible • greater number of risk factors, greater the risk of suicide • suicidal gesture- cry for help; should not be ignored, minimized, ridiculed • professional help is needed

Danger signals of seriously depressed or suicidal children/adolescents:

• Decreased school performance • Sudden gain or loss of weight • Loss of interest in activities • Decreased energy • Accident proneness • Irritability • Low self-esteem • Excessive risk-taking behavior • Concentration problems • Neglect of appearance • Talking or reading about death • Sleep problems • Aggression • Headaches, stomach and body aches • Temper tantrums • Anxiety • Suicidal thoughts or behavior • Threats by writing or hinting • History of abuse & neglect • Use of drugs or alcohol • Verbal expressions of self-death statements • History of learning disabilities and a sense of failure • Depressed mood • No longer concerned about the future • Feelings of guilt, hopelessness & helplessness • Withdrawal from family and friends • inability to see options & alternatives • feelings of being a burden on others • Giving things away • signify an abandonment of the present, & wanting something to be taken care of for the future

Danger signals for some gifted children/adolescents that indicate they may be seriously depressed or suicidal: -- self-imposed isolation from family -- deep concern with personal powerlessness -- unusual fascination with violence -- eating disorders -- chemical abuse -- rigidly compulsive behaviors -- emotionally difficulties, especially anger -- lack of prosocial activities -- excessive introspection and obsessive thinking -- difficulty separating fact from fiction (overidentification with characters, especially antiheroes and aggressive characters) -- self-imposed perfection as the ultimate standard, to the point that only tasks enjoyed are the ones completed perfectly Pat Schuler, Ph.D., NCC, LMNC Creative Insights 257-2018 [email protected] Greenmeadow Park 1654 Columbia Turnpike Castleton-on-Hudson, NY 12033 15

Recommendations for Preventing the Suicides of Gifted Adolescents (Cross, 2001) • Keep an eye out for: • emotional difficulties, especially anger or depression; • lack of prosocial activities; • dissatisfaction with place, situation, school, peers, family, or self; • difficulties in romantic relationships, especially with peers of similar abilities; • non-normative expression of overexcitabilities (predominantly negative, asocial, or antisocial); and • difficulty separating fact from fiction (overidentification with characters, especially antiheroes and aggressive characters). • Err on the side of caution. • Do not overlook potential signs of suicide just because the child is gifted. • Accept the uniqueness of gifted adolescents, but not at the risk of overlooking indicators of emotional, psychological, or suicidal distress. • Be proactive. • Educate gifted adolescents about their emotional experiences and needs. • Communicate, communicate, communicate. • Challenge the idea that suicide is an honorable solution. • Strive for balance of positive and negative themes and characters in curricula, books, and audiovisual materials. • Assess for emotional, psychological, and relational difficulties. • When in doubt, do something! In addition: • Listen! • Offer acceptance • Evaluate (Is this person at risk of making an attempt on his or her life?) • Be direct- ask • Use bibliotherapy (The Bookfinder: When Kids Need Books by Spredemann-Dreyer) • Use positive self-talk • Offer support • Help them find something to live for

Signs that Individual Counseling is Needed

• intense competitiveness • social isolation • alienation within the family • inability to control anger • excessive manipulativeness • chronic underachievement • depression or continual boredom • sexual acting out • evidence of abuse of any kind • recent traumatic experiences/ loss of a loved one Pat Schuler, Ph.D., NCC, LMNC Creative Insights 257-2018 [email protected] Greenmeadow Park 1654 Columbia Turnpike Castleton-on-Hudson, NY 12033 16

Counseling Gifted Children/Adolescents

Characteristics of Giftedness That Can Lead To Misdiagnosis (Webb, 2001) • Sensitivity • Idealism, disappointment • Impatient with self and others; intolerant • Perfectionism • Creative; non-traditional • Challenging; non conformist; disrupts status quo • Strong-willed; power struggles • “Right Brain” non linear learning styles • Neglects duties or people during • Advanced interests; diverse interests periods of intense focus • Boredom if educationally misplaced; resists routine • Asynchronous development; practice scatter of ability levels • Poor handwriting • Unusual sleep patterns • Peer relationship problems; intense; Overexcitabilities

Affective Issues/Problem Areas of Gifted and Talented Children • dyssynchrony: uneven development • avoidance of risktaking/procrastination • feeling different • excessive self-criticism • confusion about meaning of giftedness• ownership of the gift (hiding abilities) • lack of understanding from others (hostility)• multipotentiality • fear of failure; fear of success • peer relations (lack of true peers) • perfectionism; overly responsible for others • social relations • existential depression; boredom • self-concept • lack of study/organizational skills • impostor syndrome • underachievement/nonproduction • gifted children with disabilities (hidden?) • nonconformity • excessive competitiveness

Frequent Misdiagnoses of Gifted Children • Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder • Oppositional Defiant Disorder • Conduct Disorder • Intermittent Explosive Disorder • Obsessive Compulsive Disorder • Bipolar Disorder • Depression • Dysthymic Disorder (Webb, 2001)

Counseling serves to promote positive changes in an individual’s ability to cope with life. Affective Education Counseling

• Oriented toward groups • Oriented toward individual • Directed by an individual trained in counseling • Involves self-awareness and sharing of feelings with • Involves problem solving, making choices, conflict others resolution, and deeper understanding of self • Consists of planned exercises and activities • Consists of relatively unstructured private sessions or group sessions in which content is determined by students • Unrelated to therapy • Closely related to therapy • Students helped to clarify their own values or beliefs • Students helped to change their perceptions or methods of coping

Pat Schuler, Ph.D., NCC, LMNC Creative Insights 257-2018 [email protected] Greenmeadow Park 1654 Columbia Turnpike Castleton-on-Hudson, NY 12033 17

Role of Counselor in Counseling Gifted Children • Know your own giftedness • Have a strong theoretical base/knowledge of characteristics • Be aware of resources • Be creative in approach • Ask for help • Remember-gifted children have exceptional abilities • Be mindful of own value structures • Be an advocate around deviant behavior • Be yourself Issues in the Counseling Process • Identifying Giftedness/Identity • Most significant issue to be addressed • Denial of Giftedness • Child/adolescent and parent • Struggling with Deviance • Develop methods to foster their differences • Family Issues • Family therapy, parent education, support services • Family Deficits • Most delicate theme to deal with, most rewarding (Mahoney, 1994)

Areas of Questioning (Merrell (2001) Interpersonal functioning • Eating/sleeping habits • Unusual or strange perceptions or experiences • Self-attributions • Insight into own problems & circumstances • Clarity/accuracy of thought processes • Emotional status Family relationships • Quality of relationships with parents/siblings • Social support from extended family • Perceptions of family conflict & support • Responsibilities/chores/routines at home Peer relationships • Number of close friends • Preferred activities and friends (by name) • Perceived conflicts & rejection by peers School adjustment • General feelings about school • Preferred and disliked classes, subjects, & teachers • Extracurricular activities • Perceived conflicts at school Community involvement • Involvement in clubs, organizations, • Social support from others in community church, sports, etc. • Level of physical mobility within community • Part-time jobs (for teens)

Intervention Questions (Achenbach) 1. Is child’s behavior really deviant? • No? Parents, family system, teacher, others may need help 2. If child’s behavior is in need of change? • problems: particular: situation or many situations? 3. Which problem areas- highest priority? • degree of deviance- most destructive potential or competencies needing strengthening 4. What are goals of intervention in terms of child’s overall adaptive pattern? • look at entire pattern of competencies and problems • look at specific needs- not diagnostic categories 5. Do changes in child’s reported behavior show that goals of an intervention are being met? • look at unanticipated changes in other behaviors 6. How can experiences with previous cases be used to help in choosing an intervention? • be aware of particular profile patterns Pat Schuler, Ph.D., NCC, LMNC Creative Insights 257-2018 [email protected] Greenmeadow Park 1654 Columbia Turnpike Castleton-on-Hudson, NY 12033 18 Discussion Groups with Gifted Students

Benefits for your students: • PEER = soul mate or mind-mate rather than age-mate. • Differences in verbal ability or the ability for abstract thinking may affect their reluctance to self- disclose. • It may be their first opportunity to not hide who they are. • The competitive, perfectionistic student will have a place to relax. • Those who are perpetually “nice” may have an opportunity to express frustration or anger. • Those who are negative may have an opportunity to express their feelings in a positive way. • Achievers and underachievers will be able to break stereotypes of each other. • They will appreciate the “universality” of experiences.

Structuring a Group Session • Obtain parental permission. • Communicate “safety” for comfortable dialogue by having group members respond to question or survey in writing. This will help to sort, assess and objectify their feelings prior to beginning the discussion. • No one is required to speak. Anyone can “pass” in discussion. • Informational prompts from the facilitator can be effective catalysts for discussion. • Vertical self-disclosure Example: “How long have you felt this way?” • Horizontal self-disclosure Example: “Who in the group do you think feels the same way you do?” These questions are horizontal in that they connect students to one another. • Be prepared to make referrals when necessary.

Getting Started • Should they be called counseling groups • Make the groups voluntary. • State a purpose – “catalytic information” to attract them. • Discussion of giftedness becomes an affirmation. • Advertise topics to parents & teachers when beginning a group. • Address concerns about teacher-bashing. • Confidentiality is imperative. • Consider having co-facilitators: counselor and G/T specialist. • Plan on general and specific topics and come prepared with an objective for each session. • There is a need to be equitable in discussion. • Monitor non-verbal cues. • Facilitate discussion – be flexible & conclude with student restating the “focus” of the session.

What Makes the Ideal Group? • Achievers & Underachievers • Optimal size varies according to age: • Homogeneity of Age • high school: 8 – 12 • Mix genders for most purposes • elementary/middle school: 6-8 • Length of session: 40 – 60 minutes Pat Schuler, Ph.D., NCC, LMNC Creative Insights 257-2018 [email protected] Greenmeadow Park 1654 Columbia Turnpike Castleton-on-Hudson, NY 12033 19 Topics for Affective Development Understanding giftedness Social skills Self-expectations Dealing with stress Fear of failure Sensitivity Expectations of others Tolerance Feeling different Family dynamics Uneven development Responsibility for others Introversion Developing study habits Peer pressure Developing leadership ability Competitiveness Career exploration Guilt

Primary Level Intermediate Grades Self-awareness Sensitivity to others Developing friendships Leadership skills Learning to say no to strangers Values clarification Self-protection Understanding giftedness Developing appreciations Feeling different Getting along with others who are not gifted Middle/Junior/Senior High School Concerns World issues Performance Establishing positive relationships with peers Sensitivity and perfectionism Stress, both internal and external Leadership and career exploration

Counseling groups: Initial Questioning 1. What does it mean to be gifted? 1. What do your parents think about your being gifted? Your teachers? Your peers? Your siblings? 2. How is being gifted an advantage for you? A disadvantage? 3. Have you ever deliberately hidden your giftedness? If so, how? Why? 4. Would you rather be gifted girl or a gifted boy? Why? 5. How would it be (or how is it) to be gifted and African American? Latin American? Asian American? Native American? 6. What are common stereotypes of gifted students? Do any fit you? Which ones definitely do not? 7. When did you first realize you were more intelligent than most others your age? Did knowing that change anything in your life? 8. Is there a time in school (elementary, middle school, high school) when it is especially difficult to be gifted? Easier? Why?

Topics that can be adapted for use at any age level: • Giftedness –what it is; what concerns are; what the stereotypes are; how others feel about it; how we feel about it. • Where gifted children can find unconditional support. • Dealing with our own and others’ expectations. • Stress-what it is; coping strategies; sorting out stress points; deciding what can and cannot be changed; looking at “stress rhythms” at home and at school. • Anger-learning to recognize it, express it, talk about it. • Sadness and depression-learning to articulate feelings during “low times”; dealing with others who are sad. • Relationships with others-what a friend is; how one “makes friends”; how we can “read” what others do not put into words. • When we worry that we are “too much” – or too shy, too lazy, too strange, too perfectionistic, too nice, too “too” • Perfectionism-what it is; what is “sacrificed”; what it affects. Pat Schuler, Ph.D., NCC, LMNC Creative Insights 257-2018 [email protected] Greenmeadow Park 1654 Columbia Turnpike Castleton-on-Hudson, NY 12033 20 Resources

Adderholdt-Elliott, M., and Goldberg, J. (1999). Perfectionism: What's bad about being too good? Minneapolis: Free Spirit.

Alvino, J. (1985). Parents' guide to raising a gifted child. New York: Ballantine Books.

Alvino, J. (1995). Considerations and strategies for parenting the gifted child. Storrs, CT: The National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented.

Baum, S., Owen, S., & Dixon, J. (1991).To be gifted & learning disabled: From identification to practical intervention strategies. Mansfield Center, CT: Creative Learning Press.

Berger, S. L. (1999). College Planning for Gifted Students. Reston, VA: Council for Exceptional Children.

Bireley, M., & Genshaft, J. (1991). Understanding the Gifted Adolescent: Educational, Developmental, and Multicultural Issues. New York: Teachers College Press.

Cohen, L.M., & Frydenberg, E. (1996). Coping for Capable Kids: Strategies for Parents, Teachers, and Students). Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.

Coleman, L. J., and Cross, T. L. (2001). Being gifted in school: An introduction to development, guidance, and teaching. Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.

Delisle, J. R. (1992). Guiding the social and emotional development of gifted youth: A practical guide for educators and counselors. New York: Longman.

Galbraith, J. (1983, 1984, 1999). The gifted kids survival guides, I & II. Minneapolis: Free Spirit.

Gordon, T. (1975). P.E.T.: Parent Effectiveness Training. New York: Plume/Penguin.

Greene, R. W. (1998). The Explosive Child. New York: HarperCollins.

Gross, M. U. M. (1993). Exceptionally gifted children. New York: Routledge.

Heacox, D. (1991). Up from underachievement. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit.

Jacobsen, M.E. (1999). The gifted adult. New York: Ballantine Books.

Johnson, G., Kaufman, G. & Raphael, L. (2001). Stick up for yourself! Every kid's guide to personal power and positive self-esteem. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit.

Kerr, B. A. (1991). A handbook for counseling the gifted and talented. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association.

Kerr, B. A. (1985). Smart girls, gifted women. Columbus, OH: Ohio Psychology Press.

Kincher, J. (1990). Psychology for kids: 40 fun tests that help you learn about yourself. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit.

Kranowitz, C. W. (1998). The Out-of-Sync Child: Recognizing and Coping with Sensory Integration Dysfunction. New York: Perigree Publishing

Kurcinka, M. S. (1991). Raising your spirited child. New York: HarperCollins. Pat Schuler, Ph.D., NCC, LMNC Creative Insights 257-2018 [email protected] Greenmeadow Park 1654 Columbia Turnpike Castleton-on-Hudson, NY 12033 21 Lee, C. & Jackson, R. (1992). Faking it: A look into the mind of a creative learner. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook.

Lind, S. (1987). Great goof-ups. Kent, WA: Lind.

McCutcheon, R. (1985). Get off my brain: A survival guide for lazy students. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit.

Milgram, R. M. (1991). Counseling gifted and talented children: A guide for teachers, counselors, and parents. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Milgram, R. M., Dunn, R., & Price, G. E. (Eds.)(1993). Teaching and counseling gifted and talented adolescents: An international learning style perspective. Westport, CT: Praeger.

Neihart, M., Reis, S., Robinson, N., & Moon, S. (2002). The social and emotional development of gifted children: What do we know? Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.

Nowicki, S., and Duke, M. (1992). Helping the Child Who Doesn’t Fit In. Atlanta, GA: Peachtree.

Peterson, J. S. (1995). Talk with teens about feelings, family, relationships, and the future. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit.

Pipher, M. (1996). The shelter of each other: Rebuilding our families. New York: Ballantine Books.

Schmitz, C.C., & Galbraith, J. (1985). Managing the social and emotional needs of the gifted: A teacher's survival guide. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit.

Schuler, P. A. (1999). Voices of Perfectionism: Perfectionistic Gifted Adolescents in a Rural Middle School. Storrs, CT: The National Research Center on the Gifted and Talented.

Shure, M. (1994). Raising a Thinking Child. New York: Pocket Books.

Silverman, L.K. (Ed.)(1993). Counseling the gifted and talented. Denver: Love Publishing.

Smutny, J. F., Veenker, K. & Veenker, S. (1989). Your gifted child: How to recognize and develop the special talents in your child from birth to age seven. New York: Ballantine Books.

Turecki, Stanley. (1989). The Difficult Child. New York: Bantam.

Vail, R. L. (1987). Smart kids with school problems: Things to know & ways to help. New York: Penguin Books.

VanTassel-Baska, J. (Ed.) (1990). A practical guide to counseling the gifted in a school setting (2nd ed.). Reston, VA: Council for Exceptional Children.

VanTassel-Baska, J. & Olszewski-Kubilius, P. (Eds.)(1989). Patterns of influence on gifted learners: The home, the self, and the school. New York: Teachers College.

Walker, S Y. (2001). The survival guide for parents of gifted kids. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit.

Webb, J., Meckstroth, E. A., & Tolan, S. S. (1982). Guiding the gifted child: A practical source for parents and teachers. Columbus: Ohio Psychology.

Whitmore, J. R. (1980). Giftedness, conflict, and underachievement. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Winner, E. (1996). Gifted children: Myths and realities. New York: HarperCollins. Pat Schuler, Ph.D., NCC, LMNC Creative Insights 257-2018 [email protected] Greenmeadow Park 1654 Columbia Turnpike Castleton-on-Hudson, NY 12033 22 Resources on Anxiety and Stress

Website: www.stress.org

Instruments: • Adolescent Coping Scale • Taylor Manifest Anxiety Scale

Bourne, E. J. (1990). The anxiety & phobia workbook. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.

Cohen, L. and Frydenberg, E. (1996). Coping for capable kids: Strategies for parents, teachers, and students. Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.

Davis, M., Robbins, M. Eshelman, M. & McKay, M. (1998). Relaxation and stress reduction workbook. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.

Galbraith, J. & Delisle, J. Gifted kids’ survival guides. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit.

Hipp, E. (1996). Fighting invisible tigers: A stress management guide for teens. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit.

Kurcinka, M. S. (1991). Raising your spirited child. NY: HarperCollins.

Nichols, H. J. and Baum, S.(December 2001). High achievers actively engaged but secretly stressed: Keys to helping youngsters with stress reduction. Parenting for High Potential, 8- 12, 31.

Peterson, J. S. (1995). Talk with teens about self and stress. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit.

Peterson, J. S. (1995). Talk with teens about feelings, family, relationships and the future. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit.

Rapee, R. M., Spence, S.H., Cobham, V., & Wignall, A. (2000). Helping your anxious child. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.

Rapee, R, M., Wignall, A., Hudson, J.L., & Schniering, C.A. (2000). Treating anxious children and adolescents: An evidence-based approach. Oakland, CA: New Harbinger.

Reira, M. (1997). Surviving high school: Making the most of your high school years. Berkeley, CA: Celestial Arts.

Romain, T. and Verdick, E. (2000). Stress can really get on your nerves. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit.

Vizzini, N. (2000). Teen angst? Naaah… Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit. Pat Schuler, Ph.D., NCC, LMNC Creative Insights 257-2018 [email protected] Greenmeadow Park 1654 Columbia Turnpike Castleton-on-Hudson, NY 12033 23

Depression and Suicide

Appleby, M., & Condonis, M. (1990). Hearing the cry. Sydney: Rose Educational Training and Consultancy.

Blauney, S. R. (2002). How I Stayed Alive When My Brain Was Trying to Kill Me: One Person’s Guide to Suicide Prevention. New York: HarperCollins.

Cross, T. L. (2001). On the social and emotional lives of gifted children. Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.

Cross, T. L., Gust-Brey, K., & Ball, R. B. (2002). A psychological autopsy of the suicide of an academically gifted student: Researchers’ and Parents’ Perspectives. Gifted Child Quarterly, 46 (4), 247-259.

Delisle, J., & Galbraith, J. (2002). When Gifted Kids Don’t Have All the Answers. Minneapolis, MN: Free Spirit.

Koplewicz, H. More Than Moody: Recognizing and Treating Adolescent Depression.

Papolos & Papolos. (1992). Overcoming Depression.

Portner, J. (2001). One In Thirteen: The Silent Epidemic of Teen Suicide. Beltsville, MD: Robins Lane Press.

Special Issue (Suicide) of The Journal of Secondary Gifted Education (Spring 1996, vol. 7, no. 3)

Magazines Understanding Our Gifted Open Space Communications, Inc. 1900 Folsom, Suite 108 Boulder, CO 80302 1-800-494-6178

The Journal of Secondary Gifted Education Gifted Child Today Magazine Creative Kids Prufrock Press P.O. Box 8813 Waco, TX 76714-8813 1-800-998-2208

Parenting for High Potential Roeper Review Gifted Child Quarterly P.O. Box 329 National Association for Gifted Children Bloomfield Hills, MI 48303 1707 L Street NW, Suite 550 248-203-7321 Washington, DC 20036 202-785-4268 Pat Schuler, Ph.D., NCC, LMNC Creative Insights 257-2018 [email protected] Greenmeadow Park 1654 Columbia Turnpike Castleton-on-Hudson, NY 12033 24