Rooibos and Honeybush Tea United Nations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Finding Fynbos of the Western Cape, Via Grootbos

Finding Fynbos Of The Western Cape, Via Grootbos A Professional & Personal Journey To South Africa September 13th - 21st October 2018 By Victoria Ind !1 Table Of Contents 1………………………Itinerary 2………………………Introduction 3…………………….. Grootbos - My Volunteering - Green Futures Plant Nursery & Farms 4…………………….. Botanising - Grootbos Conservation Team - Hike With Sean Privett - Milkwood Forest - Self-Guided Botanising 5…………………….. Fernkloof Flower Festival 6……………………Garden Visits - Vergelegen - Lourensford - Stellenbosch - Dylan Lewis Sculpture Garden - Kirstenbosch - Green Point Diversity Garden - The Company’s Garden 7…………………… Conclusion 8…………………… Breakdown Of Expenses 9……………………. Appendix & Bibliography 10………………….. Acknowledgments !2 1: ITINERARY 13th-15th September 2018: Travel from Dublin Ireland to Cape Town. x2 nights in Cape Town. 15th September 2018: Collection from Cape Town by Grootbos Foundation, transport to Grootbos staff accommodation, Gansbaai. 16th September-15th October 2018: Volunteer work with Green Futures, a division of the Grootbos Foundation. Mainly based on the Grootbos Nature Reserve & surrounding areas of Gansbaai & Masakhane township. 20-23rd September 2018: Weekend spent in Hermanus, attend Fernkloof Flower Festival. 15th October 2018: Leave Grootbos, travel to Cape Town. 16th October 2018: Visit to Vergelegen 17th October 2018: Visit to Lourensford & Stellenbosch 18th October 2018: Visit to Dylan Lewis Sculpture Garden 19th October 2018: Visit to Kirstenbosch Botanic Garden 20th October 2018: Visit to Green Point Diversity Garden & Company Gardens 21st October 2018: Return to Dublin Ireland. Fig: (i) !3 2: INTRODUCTION When asked as a teenager what I wanted to do with my life I’d have told you I wanted to be outdoors and I wanted to travel. Unfortunately, as life is wont to do, I never quite managed the latter. -

House Specials : Original Blend Teas

House Specials : Original House Specials : Original Blend Teas <Black> Blend Teas <Green > Lavegrey: Jasmine Honey: Our unique Creamy Earl Grey + relaxing Lavender. Jasmine green tea + honey. One of the most popular Hint of vanilla adds a gorgeous note to the blend. ways to drink jasmine tea in Asia. Enjoy this sweet joyful moment. Jasmine Mango: London Mist Jasmine + Blue Mango green tea. Each tea is tasty in Classic style tea: English Breakfast w/ cream + their own way and so is their combination! honey. Vanilla added to sweeten your morning. Strawberry Mango: Lady’s Afternoon Blue Mango with a dash of Strawberry fusion. Great Another way to enjoy our favorite Earl Grey. Hints combination of sweetness and tartness that you can of Strawberry and lemon make this blend a perfect imagine. afternoon tea! Green Concussion: Irish Cream Cherry Dark Gun Powder Green + Matcha + Peppermint Sweet cherry joyfully added to creamy yet stunning give you a little kick of caffeine. This is a crisp blend Irish Breakfast tea. High caffeine morning tea. of rare compounds with a hidden tropical fruit. Majes Tea On Green: Natural Raspberry black tea with a squeeze of lime Ginger green tea + fresh ginger and a dash of honey to add tanginess after taste. to burn you calories. Pomeberry I M Tea: Pomegranate black tea with your choice of adding Special blend for Cold & Flu prevention. Sencha, Blackberry or Strawberry flavoring. Lemon Balm and Spearmint mix help you build up your immunity. Minty Mint Mint black tea with Peppermint. A great refreshing Mango Passion: drink for a hot summer day. -

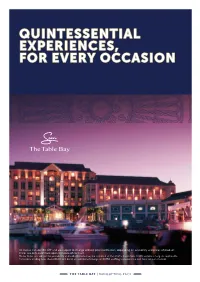

Quintessential Experiences, for Every Occasion

QUINT ESSENTIA L EXP ERIE NCES, FOR EVERY OCC ASION All menus include 15% VAT and are subject to change without prior notification, depending on availability and prices of product. Prices are only confirmed upon sign ature of contract. Menu items are subject to availability and substitutions may be required at the chef’s discretion. A 10% service charge is applicable. Functions ending later than 23h00 will incur an additional charge of R1750 staffing transport fee per hour or part the reo f. THE TABLE BAY | BANQUETING PACK AFRICA’S MOST BEAUTIFUL CITY Cape Town is the Mother Ci ty of Afri ca , regarded as one of the most beauti ful regi ons in the wor ld . The ci ty pro vi des a setti ng for many sceni c wonder s, ma gnif icent seas cape s and panor amic vista s. Home to the iconic Table Mo unta in; a natu ral wonder of the wor ld . Cape Point, the dramati c promo ntory whe re the wa rm Indi an Ocea n meets the cold Atlanti c. Robben Is land, a Wor ld Her itage Site whe re Ne lson Mandela was inc arcer ated from 1964 to 19 82. Cape Town offers the pe rfec t comb in ati on of rich he ri tag e, his tori cal legacy and natural beauty. THE TABLE BAY | BANQUETING PACK A GATEWAY TO THE CAPE’S BREATHTAKING SCENERIES JOURNEY TO THE TOP OF A NATURAL WONDER SEE A POINT WHERE OCEANS ME RGE DISCOVER A SYMBOL OF FREEDOM THE TABLE BAY | BANQUETING PACK BE CAPTI VATE D BY PERENNIAL BEAUT Y The Table Ba y, opened in May 1997 by iconic former South Africa p resident, Nelson Mandela, is situated on the historic Victoria and Alfred Waterf ront. -

Champagne Tea

Champagne Tea SANDWICHES & SAVORIES herb-roasted prime rib horseradish cream, watercress, brioche slider foie gras mousse, black cherry jam, brioche crostini peekeytoe crab, celery, avocado, lemon, sour cream, squid ink cornet porcini mushroom quichette, porchini oil, whipped cream cheese lobster roll, daikon sprouts, buttered potato roll caviar blini daurenki caviar SCONES freshly baked warm seasonal scones, double devonshire cream, lemon curd, preserves PASTRIES & SWEETS mont blanc sablé, chestnut vermicelli, huckleberry compote, vanilla cream carmalized pineapple, coconut rum chouquette, coconut cake daquoise lemon and poppyseed cake, preserved lemon, earl grey tea and bergamot ganache dark chocolate kugelophf, dark chocolate and cognac ganache mandarin orange chocolate and pain d’épice éclair fresh seasonal fruit tart tonka bean and banana gold macaron WITH A GLASS OF NV VEUVE CLICQUOT BRUT CHAMPAGNE or NV MOËT & CHANDON BRUT ROSÉ IMPÉRIAL CHAMPAGNE 99 PER PERSON WITH A GLASS OF KRUG GRANDE CUVÉE CHAMPAGNE 129 PER PERSON 18% GRATUITY WILL BE APPLIED TO A CHECK FOR PARTIES OF 6 OR MORE We invite you to join our online community at Dine at The Plaza @dineattheplaza @theplazahotel The New Yorker Tea SANDWICHES & SAVORIES smoked salmon, pumpernickel, chive whipped cream cheese, dill organic deviled egg salad, dill pickle relish, white bread oven-roasted turkey, granny smith cream cheese, sourdough bread english cucumber, minted goat cheese green goddess, rye bread smoky mountain country ham, comte cheese, spicy mustard, pretzel ficelle -

“Just a South African Girl Living in an Alabama World”

“Just a South African Girl Living in an Alabama World” Earlier this month, a friend battling brain cancer shared that he had become frustrated being unable to visit mountainous areas where he could take in the beautiful colors of fall. His illness restricts him from a number of things he wishes to do. However, in the same breath, he mentioned how he had failed to notice the tree God placed in front of his own home that was absolutely radiant with the various shades fall brings. God’s beauty, so evident! The following weekend I explored Moss Rock, a beautiful preserve with such incredible scenery, a great suggestion from my friend. As I walked, I prayed, thanking the Lord for His immaculate creation. The colors of fall were incredible. I was reminded of my friend’s longing to see the colors, and I “just so happened” to have my camera with me. I snapped a few pictures, excited to share the photos! Such beauty! The deep orange colors of the leaves reminded me of the story in Exodus where the Lord spoke to Moses through the burning bush. I found a comfortable place to sit as I opened the scriptures, desperate to hear from the Lord. Why did He draw me to the story of the burning bush? I soaked in each word, to the extent that I even took my shoes off, as Moses did on Holy ground, longing for the Lord to speak to me as He did with Moses. The following scripture moved my heart: "...Who makes a person's mouth? Who decides whether people speak or do not speak, hear or do not hear, see or do not see? Is it not I, the Lord?" - Exodus 4:11 It was then I felt convicted. -

Destination Guide Spectacular Mountain Pass of 7 Du Toitskloof, You’Ll See the Valley and Surrounding Nature

discover a food & wine journey through cape town & the western cape Diverse flavours of our regions 2 NIGHTS 7 NIGHTS Shop at the Aloe Factory in Albertinia Sample craft goods at Kilzer’s permeate each bite and enrich each sip. (Cape Town – Cape Overberg) (Cape Town – Cape Overberg and listen to the fascinating stories Kitchen Cook and Look, (+-163kms) – Garden Route & Klein Karoo) of production. Walk the St Blaize Trail The Veg-e-Table-Rheenendal, Looking for a weekend break? Feel like (+-628kms) in Mossel Bay for picture perfect Leeuwenbosch Factory & Farm store, a week away in an inspiring province? Escape to coastal living for the backdrops next to a wild ocean. Honeychild Raw Honey and Mitchell’s We’ve made it easy for you. Discover weekend. Within two hours of the city, From countryside living to Nature’s This a popular 13.5 km (6-hour) hike Craft Beer. Wine lover? Bramon, Luka, four unique itineraries, designed to you’ll reach the town of Hermanus, Garden. Your first stop is in the that follows the 30 metre contour Andersons, Newstead, Gilbrook and help you taste the flavours of our city the Whale-Watching Capital of South fruit-producing Elgin Valley in the along the cliffs. It begins at the Cape Plettenvale make up the Plettenberg and 5 diverse regions. Your journey is Africa. Meander the Hermanus Wine Cape Overberg, where you can zip-line St. Blaize Cave and ends at Dana Bay Bay Wine Route. It has recently colour-coded, so check out the icons Route to the wineries situated on an over the canyons of the Hottentots (you can walk it in either direction). -

The Way of Tea

the way of tea | VOLUME I the way of tea 2013 © CHADO chadotea.com 79 North Raymond Pasadena, CA 91103 626.431.2832 DESIGN BY Brand Workshop California State University Long Beach art.csulb.edu/workshop/ DESIGNERS Dante Cho Vipul Chopra Eunice Kim Letizia Margo Irene Shin CREATIVE DIRECTOR Sunook Park COPYWRITING Tek Mehreteab EDITOR Noah Resto PHOTOGRAPHY Aaron Finkle ILLUSTRATION Erik Dowling the way of tea honored guests Please allow us to make you comfortable and serve a pot of tea perfectly prepared for you. We also offer delicious sweets and savories and invite you to take a moment to relax: This is Chado. Chado is pronounced “sado” in Japanese. It comes from the Chinese words CHA (“tea”) and TAO (“way”) and translates “way of tea.” It refers not just to the Japanese tea ceremony, but also to an ancient traditional practice that has been evolving for 5,000 years or more. Tea is quiet and calms us as we enjoy it. No matter who you are or where you live, tea is sure to make you feel better and more civilized. No pleasure is simpler, no luxury less expensive, no consciousness-altering agent more benign. Chado is a way to health and happiness that people have loved for thousands of years. Thank you for joining us. Your hosts, Reena, Devan & Tek A BRIEF HISTORY OF CHADO Chado opened on West 3rd Street in 1990 as a small, almost quaint tearoom with few tables, but with 300 canisters of teas from all over the globe lining the walls. In 1993, Reena Shah and her husband, Devan, acquired Chado and began quietly revolutionizing how people in greater Los Angeles think of tea. -

FODMAP Everyday Low FODMAP Foods List- Full Color 9.26.17

Corn tortillas, with gums or added fiber Corn tortillas, without gums or added fiber All plain fish Gluten free bread, white All plain meats: beef, lamb, pork Gluten free bread, low gi, high fiber All plain poultry Gluten free bread, high fiber Butter beans canned, rinsed Gluten free bread, multigrain Chana dal, boiled Gluten free rice chia bread Chickpeas (garbanzo), canned, rinsed Millet bread Eggs Sourdough oat bread Egg Replacer Sourdough spelt bread Lentils, canned, rinsed Spelt bread 100% Lentils, green, boiled Sprouted multigrain bread Lentils, red, boiled White bread Lima beans, boiled Whole-wheat sourdough Mung beans, boiled Mung beans, sprouted Quorn, minced Salmon, canned in brine, drained This shopping and reference list is updated monthly to conform Sardines, canned in oil, drained with the most up-to-date research gathered from Monash Sausage, German bratwurst University, the USDA and other reputable sources. Almond milk Shrimp/prawns, peeled Coconut milk, canned Tempeh, plain Please refer to the Monash University smartphone app or their Coconut milk, UHT printed booklet for serving size information. Some foods are Tofu, firm & extra firm, drained only low FODMAP in 1-teaspoon amounts, so it is vital that you Cottage cheese Tuna, canned in brine, drained use this in conjunction with a Monash University reference. Cow’s milk, lactose-free Tuna, canned in oil, drained Hemp milk Urid dal, boiled Foods not listed are either high FODMAP or have not been Macadamia milk tested yet. Oat milk We encourage you to eat broadly and test yourself for Quinoa milk, unsweetened tolerances. Working with a registered dietician is the best way Rice milk to monitor your reactions and progress. -

Welkom Bij De Pannekoekenbakker

Welkom bij De Pannekoekenbakker We bakken pannenkoeken voor iedereen. Maak een keuze uit de menukaart, geef uw wensen door aan uw gastheer of gastvrouw en onze keukenbrigade bakt speciaal voor u de gewenste pannenkoek! Onze inventieve chef-koks bedenken steeds weer bijzondere recepten en daarom kent onze menukaart een verrassende, ruime en niet alledaagse keuze. Gastvrijheid en de continue kwaliteit van onze pannenkoeken staan daarbij hoog in het vaandel. Indien u dat wenst dan kunt u onze pannenkoeken ook bestellen in een “spelt” variant. Heeft u speciale (di)eetwensen of bent u overgevoelig voor bepaalde ingrediënten? Meld het ons. Wij zullen ons uiterste best doen om hier rekening mee te houden*. U kunt onze pannenkoeken ook in een kleiner formaat bestellen. Wij rekenen dan 15% minder van de vermelde prijs. Wij wensen u een gezellig verblijf en smakelijk eten! * Aangezien onze keuken niet allergenen vrij is, kunnen wij geen 100% garantie geven dat er geen sporen van allergenen aanwezig kunnen zijn in onze gerechten. Koude- en warme dranken Koude dranken Koffie 430 Coca-Cola 2,20 Zie onze speciale koffie’s op de volgende 431 Coca-Cola light 2,20 bladzijde bij de voor- en nagerechten. 432 Coca-Cola zero sugar 2,20 460 Koffie 2,20 433 Fanta orange 2,20 461 Koffie met slagroom 2,70 434 Fanta cassis 2,20 462 Espresso 2,20 435 Sprite 2,20 463 Caffeïnevrije koffie 2,20 436 Chaudfontaine still 2,20 464 Cappuccino 2,40 437 Chaudfontaine sparkling 2,20 465 Cappuccino groot 3,00 438 Rivella 2,20 466 Koffie verkeerd 3,00 439 Schweppes Indian tonic -

Drinks Menu What's Next?

SOFT DRINKS JUICES DRINKS MENU & BLENDED DRINKS Soda (300ml) 200 TEA & COFFEE *Please ask a member of staff for our coffee menu (500ml plastic) 230 Fresh Fruit Juice (small) 300 Bush Coffee (small/large) 325 / 400 Diet Coke (300ml) 220 (large) 380 (500ml plastic) 250 Freshly brewed Kenyan filter coffee. Mangowizi (500ml) 350 Red Bull 350 Hot Chocolate 300 Fresh mango and Stoney ginger beer Still Water (500ml) 220 Rich, creamy chocolate with hot milk. (available when mangoes are in season) (1 litre) 280 DelMonte Juice Packet 1,000 Pot of Tea 275 Sparkling Water (1 litre) 340 Lime Cordial 100 Kenyan, Pepermint, Rooibos, Chamomile, Earl Grey or Forest Fruit. Enough for two to share. BEERS African Mixed Tea 300 Local beers 380 Kenyan tea brewed with milk, with sugar on the side. International beers 420 MILKSHAKES & SMOOTHIES SPIRITS (per tot) Banana, Honey and Cinnamon Smoothie 450 Johnnie Walker Red 350 Gilberys Gin 350 Whole bananas, honey, yoghurt & fresh milk. Johnnie Walker Black Label 480 Baileys 450 Vanilla Shake 450 Jameson 350 Amarula 450 Vanilla ice cream, fresh milk. Jack Daniels 450 Sambuca 400 Chocolate Shake 450 Glenfiddich 550 Cointreau (Tequila) 400 Chocolate ice cream, fresh milk, chocolate syrup. Myres Rum 300 Camino Real 370 Bacardi white 320 Viceroy (Brandy) 300 Strawberry Shake 450 Malibu 350 Hennessy (Cognac) 600 Strawberry ice cream, fresh fruit, milk, strawberry syrup. Smirnoff Vodka Red 300 Martel (Cognac) 550 Mango Shake 450 Gordons Gin 300 Martini Bianco 300 Vanilla ice cream, fresh mango, milk (available when mangoes are in season). BOOZY COFFEEs Check out the blackboard for today’s special shakes Hot BOOZY SHAKES Irish Coffee 800 WHAT’S NEXT? Coffee, Irish whisky, cream. -

Rooibos & Raisins

ROOIBOS & RAISINS CRAFTS: MAMMA THEMBA TABLE Cocktail: Rooibos Aqua Martini Buttermilk and Biltong Scones Cape Malay style curry Balsamic Babotie with a buttermilk custard Easy Jam Orange Sultana rice Baked Baby Marrow Individual Cape Velvet Malva’s Brandy ice cream Debbie Hannibal 082 882 2227 [email protected] www.cookstudio.co.za http://pinterest.com/Cookstudio www.facebook.com/cookstudio @thecookstudio Rooibos “Aqua” Martini (2) COOK August 2009 Rooibos & Raisins 1 1 shot (25ml) Cinzano Rosso 2 shots (25ml) Van Der Hum 4 shots (100ml) cold strong rooibos* 1. Shake the ingredients over ice and pour into a martini glass 2. Garnish with a twist of lemon or a slither of naartjie peel COOK’S NOTES: To make rooibos add 1 teabag to 100ml of boiling water and allow to infuse. Add sugar or honey to taste if you would like a sweeter cocktail Buttermilk and Biltong scones (12-15) 3 cups cake flour 5 teaspoons baking powder 5 teaspoons sugar 1 teaspoons salt ½ cup biltong powder/grated biltong 2 extra- large free range eggs 1 cup cream 1 cup buttermilk 1. Preheat the oven to 220˚C 2. Mix all the dry ingredients and make a well in the centre 3. Combine eggs, cream and buttermilk and add to the flour 4. Stir with a knife until the dough comes together 5. Turn the sticky dough out onto a floured surface 6. Lift and drop the dough a couple of times till soft 7. Place enough of the mixture in a greased muffin pan hole, to just reach the top (you should get 12 in a regular muffin pan and 15 in the slightly smaller one-not a mini pan) 8. -

South African Cuisine

University of Buxton, Derby ITM-IHM Oshiwara, Mumbai 2012-2013 SOUTH AFRICAN CUISINE Course Coordinators: Veena Picardo Sanket Gore Submitted by: Prasad Chavan (OSH2012GD-CA2F006) Mahi Baid (OSH2012BA-CA2F014) 1 Contents South Africa and its Food 3 Sunny South Africa 4 History 6 The Rainbow Cuisine 8 South Africa Celebrates 12 Braai and PotJiekos 13 Tourism and South African Delights 14 The Story of the Cultures 15 Bibliography 16 2 SOUTH AFRICA AND ITS FOOD South Africa cannot be defined as a singular culture. The centuries of colonization have rendered it so rich in diversity that now all the disarray in heritage has aligned itself to make it a unique country. The acceptance of the distinct heritages by people of the country does not comply with the discrimination of the apartheid that the country suffered for so long. But today, South Africa has a lot of culture to show and many experiences to share. The Braai and the Potjiekos express the affection for meat; the Atjars and the Sambals show the appreciation of flavour; the Pap shows how a South African loves a hearty meal; and the homebrewed beer reflect upon the importance of social activity for a South African. The country maybe associated with wild life sanctuaries and political convolutedness, but it has many more stories to tell, and many a palates to unveil. The tastes of the country reflect its history and demonstrate the way in which this complicated web of cultures was built. But like a snowflake, South Africa makes this “Rainbow culture” seem natural and yet intriguing, exceptional in all senses of the word.