Viruses That Infect Plants Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 the Global Flower Bulb Industry

1 The Global Flower Bulb Industry: Production, Utilization, Research Maarten Benschop Hobaho Testcentrum Hillegom, The Netherlands Rina Kamenetsky Department of Ornamental Horticulture Agricultural Research Organization The Volcani Center Bet Dagan 50250, Israel Marcel Le Nard Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique 29260 Ploudaniel, France Hiroshi Okubo Laboratory of Horticultural Science Kyushu University 6-10-1 Hakozaki, Higashi-ku Fukuoka 812-8581, Japan August De Hertogh Department of Horticultural Science North Carolina State University Raleigh, NC 29565-7609, USA COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL I. INTRODUCTION II. HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVES III. GLOBALIZATION OF THE WORLD FLOWER BULB INDUSTRY A. Utilization and Development of Expanded Markets Horticultural Reviews, Volume 36 Edited by Jules Janick Copyright Ó 2010 Wiley-Blackwell. 1 2 M. BENSCHOP, R. KAMENETSKY, M. LE NARD, H. OKUBO, AND A. DE HERTOGH B. Introduction of New Crops C. International Conventions IV. MAJOR AREAS OF RESEARCH A. Plant Breeding and Genetics 1. Breeders’ Right and Variety Registration 2. Hortus Bulborum: A Germplasm Repository 3. Gladiolus 4. Hyacinthus 5. Iris (Bulbous) 6. Lilium 7. Narcissus 8. Tulipa 9. Other Genera B. Physiology 1. Bulb Production 2. Bulb Forcing and the Flowering Process 3. Morpho- and Physiological Aspects of Florogenesis 4. Molecular Aspects of Florogenesis C. Pests, Physiological Disorders, and Plant Growth Regulators 1. General Aspects for Best Management Practices 2. Diseases of Ornamental Geophytes 3. Insects of Ornamental Geophytes 4. Physiological Disorders of Ornamental Geophytes 5. Exogenous Plant Growth Regulators (PGR) D. Other Research Areas 1. Specialized Facilities and Equipment for Flower Bulbs52 2. Transportation of Flower Bulbs 3. Forcing and Greenhouse Technology V. MAJOR FLOWER BULB ORGANIZATIONS A. -

Tyler Schmidt, Plant Science Major, Department of Horticultural Science

Interspecific Breeding for Warm-Winter Tolerance in Tulipa gesneriana L. Tyler Schmidt, Plant Science Major, Department oF Horticultural Science 19 December 2015 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Focus on breeding of Tulipa gesneriana has largely concentrated on appearance. Through interspecific breeding with more warm-tolerant species, tolerance of warm winters could be introduced into the species, decreasing dormancy requirements and expanding the range of tulips southward. Additionally, long-lasting foliage can be favored in breeding to allow plants to store more energy for daughter bulbs. Continued virus and fungal resistance breeding will decrease infection. Primary benefits are for gardeners and landscapers who, under the current planting schedule, are planting tulip bulbs annually, wasting money. Producers benefit from this by reducing cooling times, saving energy, greenhouse space, and tulip bulbs lost to diseases in coolers. UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA AQUAPONICS: REPORT TITLE 1 I. INTRODUCTION A. Study species Tulips (Tulip gesneriana L.) are one of the most historically significant and well-known horticultural crops in the world. Since entering Europe via Constantinople in the mid-sixteenth century, the Dutch tulip market became one of the first “economic bubbles” of modern civilization, creating and destroying fortunes in four brief years (Lesnaw and Ghabrial, 2000). Since this time, tulips have remained extremely popular as more improved cultivars are released. However, a problem remains: even though viral resistance and long-lasting cultivars are introduced, few are capable of surviving in a climate with truly mild winters and only select cultivars are able to store enough energy for another year of flowering, even in climates with colder winters. Current planting schemes suggest planting annually, wasting tulip bulbs (Dickey, 1954). -

Aphid Transmission of Potyvirus: the Largest Plant-Infecting RNA Virus Genus

Supplementary Aphid Transmission of Potyvirus: The Largest Plant-Infecting RNA Virus Genus Kiran R. Gadhave 1,2,*,†, Saurabh Gautam 3,†, David A. Rasmussen 2 and Rajagopalbabu Srinivasan 3 1 Department of Plant Pathology and Microbiology, University of California, Riverside, CA 92521, USA 2 Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology, North Carolina State University, Raleigh, NC 27606, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Entomology, University of Georgia, 1109 Experiment Street, Griffin, GA 30223, USA; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]. † Authors contributed equally. Received: 13 May 2020; Accepted: 15 July 2020; Published: date Abstract: Potyviruses are the largest group of plant infecting RNA viruses that cause significant losses in a wide range of crops across the globe. The majority of viruses in the genus Potyvirus are transmitted by aphids in a non-persistent, non-circulative manner and have been extensively studied vis-à-vis their structure, taxonomy, evolution, diagnosis, transmission and molecular interactions with hosts. This comprehensive review exclusively discusses potyviruses and their transmission by aphid vectors, specifically in the light of several virus, aphid and plant factors, and how their interplay influences potyviral binding in aphids, aphid behavior and fitness, host plant biochemistry, virus epidemics, and transmission bottlenecks. We present the heatmap of the global distribution of potyvirus species, variation in the potyviral coat protein gene, and top aphid vectors of potyviruses. Lastly, we examine how the fundamental understanding of these multi-partite interactions through multi-omics approaches is already contributing to, and can have future implications for, devising effective and sustainable management strategies against aphid- transmitted potyviruses to global agriculture. -

Accumulation of Viral Coat Protein in Chloroplasts of Lily Leaves Infected with Lily Mottled Virus

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURE & BIOLOGY ISSN Print: 1560–8530; ISSN Online: 1814–9596 17F–036/2017/19–5–1265–1269 DOI: 10.17957/IJAB/15.0436 http://www.fspublishers.org Full Length Article Accumulation of Viral Coat Protein in Chloroplasts of Lily Leaves Infected with Lily Mottled Virus Pinsan Xu1,2, Xiuying Xia1, Jiong Song1 and Zhengyao Zhang2* 1School of Life Science and Biotechnology, Dalian University of Technology, Dalian Liaoning 116024, China 2School of Life Science and Medicine, Dalian University of Technology, Panjin Liaoning 124221, China *For correspondence: [email protected]; [email protected] Abstract The symptoms of Lily mottled virus (LMoV) disease are thought to be caused by metabolic changes in leaf chloroplasts. To observe variations in the ultrastructure of cells and the accumulation of viral coat protein (CP) in lily leaves, we examined ultrathin sections of lily leaves infected by LMoV. Immunogold labeling analysis demonstrated that LMoV-CP was localized to the chloroplasts. The chlorophyll fluorescence parameters of LMoV-infected lily, which indicating that the accumulation of LMoV-CP in chloroplasts inhibits PSII activity. We investigated the transmembrane transport of LMoV CP by incubating a gradient of this protein. The lowest concentration of LMoV-CP detected was 30 μg mL-1 and the optimal incubation time was 1 min. High levels of LMoV-CP that accumulate inside chloroplasts may affect photosynthesis in virus-infected lily by inhibiting photosystem activity. © 2017 Friends Science Publishers Keywords: Virus infection; Cell ultrastructure; Chloroplasts; Coat protein Introduction CP concentration and time). However, the molecular mechanism underlying how LMoV causing LMoV Lily mottled virus (LMoV) is one of the main viruses symptoms remains unclear. -

Development of in Vitro Lily Scale Budlets As Related to Virus Elimination

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Joanne C. Ruttum for the degree of Master of Science in Botany and Plant Pathology presented on June 27, 1991. Title: Development of in vitro Lily Scale Bulblets as Related to Virus Elimination -Redacted for Privacy_ Abstract approved: Thomas C. Allen, Jr. Lily hybrids vary in their ability toproduce virus-free (VF) bulblets when grown fromvirus-infected scalesintissue culture. Asiatic hybrids typically produce a higher percentage of in vitro VFscale bulblets than do Lilium longiflorum cultivars. Three hypotheses concerning the cause of this variation are tested onfive lily hybrids: an Asiatic hybrid, two L. longiflorum cultivars, an Oriental hybrid and L. candidum. The first hypothesis states that VFscale bulblets originate from wound tissue that is naturallylow in virus concentration and blocks the passage of virusparticles from one cell to the next. The second hypothesis says that scale-to-bulblet vascular connections, which serve asvirus pathways, occur inhybrids showing high percentages of virus-infected scale bulblets, while connections are absent in those hybridswithlow numbersof virus-infected bulblets. The third hypothesis concerns the virus concentration in the scale at the site of bulblet origin: bulblets of hybrids producing large numbers of VF bulblets originate from scale tissues low in virus concentration; bulblets of low percentage VF bulblet hybrids originate from scale tissues high in virus concentration. The first two hypotheses are not supported by the results of thisstudy. First, lily bulblets do not originate from wound tissue. Second,scale-to-bulblet vascular connections consistently occur in 'Enchantment,' an Asiatic hybrid, and occasionally occur in L. candidum. -

Interceptation of Viruses on Foreign Tulips in Brazil

InterceptationSCIENTIFIC of viruses COMMUNICATION on foreign tulips in Brazil. 501 INTERCEPTATION OF VIRUSES ON FOREIGN TULIPS IN BRAZIL E.B. Rivas, S.R. Galleti, M.A.V. Alexandre, L.M.L. Duarte, C.M. Chagas Instituto Biológico, Centro de Pesquisa e Desenvolvimento de Sanidade Vegetal, Av. Cons. Rodrigues Alves, 1252, CEP 04014-002, São Paulo, SP, Brasil. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT Sixty-seven tulip samples intercepted from the Netherlands by the Brazilian Agriculture Ministry, between 2004 and 2006, and two samples from São Paulo local market, Brazil, were assayed by serological and biological techniques, as well as by electron microscopy observations, for virus screening. In bulbs from the Netherlands potexviruses were detected in five samples and tobamoviruses in other three. Symptoms induced in some differential hosts were similar to those caused by Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV), while serological results indicated an infection by Tulip virus X. In two tulip samples from local flower shops, a Potyviridae was identified based on the presence of flexuous particles and cytoplasmic cylindrical inclusions. Mechanical transmission tests to potyvirus hosts in the Amaranthaceae, Chenopodiaceae and Solanaceae species were negative, making possible to exclude a possible infection by Turnip mosaic viru, a common virus species in tulips. Although TVX could be detected in intercepted tulip bulbs from the Netherlands, the virus is only reported in Scotland, Japan and USA. KEY WORDS: Ornamental plant, Potexvirus, Tobamovirus, Potyviridae. RESUMO INTERCEPTAÇÃO DE VÍRUS EM TULIPAS IMPORTADAS PELO BRASIL. Sessenta e sete amostras de tulipas interceptadas da Holanda pelo Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abaste- cimento, entre os anos de 2004 e 2006, e duas amostras, adquiridas no comércio local de São Paulo, foram avaliadas para a presença de vírus por meio de ensaios biológicos, sorológicos e observações ao microscópio eletrônico. -

'Broken'tulips and Tulip Breaking Virus

‘Broken’tulips and Tulip breaking virus ue to their beauty, range popular in Europe and, soon after, of colours and early bulbs were distributed from Vienna to flowering, tulips have Augsberg, Antwerp and Amsterdam, remained popular as and subsequently to other European garden plants and cut cities. blooms since they were DDfirst imported into Europe from Asia Tulip breaking virus Minor and Persia more than four and a Of the viruses now known to infect half centuries ago. Their introduction is tulips and cause ‘breaking’, the best usually attributed to Ogier de Bus- known is Tulip breaking virus (TBV) becque who, in 1554, first sent tulip which induces leaf chlorosis and, in bulbs and seeds to Vienna. This, of coloured cultivars, ‘broken’ flowers. course, was only a few years after the Breaking, or rectification as it was also deaths of great historical figures such earlier known, describes the appear- as Henry VIII, Martin Luther, Pope ance of the flowers in which the petals, Clement VII and Francis I of France, instead of being uniformly coloured, and when Tsar Ivan IV (Ivan the are variegated due to the irregular Terrible) was at his most powerful. It distribution of anthocyanin. Such is interesting that Busbecque, Ambas- ‘broken’ flowers are known to have ᭡ Illustration of ‘Tulip cv. Semper Augustus’ sador of Ferdinand I, the Holy Roman occurred in tulips in Europe within a taken from The Tulip Book (circa 1630– Emperor, to the great Sultan Souleiman, decade or so of their introduction and It’s hard to believe that in the 17th century people yearned 1639). -

Is the Foliar Yellow Vein of Some Ornamental Plants Caused by Plant

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School 2014 Is the foliar yellow vein of some ornamental plants caused by plant viruses? Favio Eduardo Herrera Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Plant Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Herrera, Favio Eduardo, "Is the foliar yellow vein of some ornamental plants caused by plant viruses?" (2014). LSU Master's Theses. 218. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/218 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IS THE FOLIAR YELLOW VEIN OF SOME ORNAMENTAL PLANTS CAUSED BY PLANT VIRUSES? A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in The Department of Plant Pathology and Crop Physiology by Favio Herrera Egüez B.S., Pan American School of Agriculture Zamorano, 2010 May 2014 To my grandparents, Cesar and Sara ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thanks to God for giving the health and strength to accomplish step in important task in my life. Thanks for giving me a family who supports me from the distance. I would like to thank Dr. Rodrigo Valverde for his patience, effort and guidance during this time and for giving me a chance to continue with my studies besides my expertise in this field. -

Virus Groups 2 1 Group Name Group Strain Type Shape No

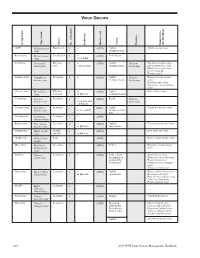

VIRUS GROUPS 2 1 Group Name Group Strain Type Shape No. of Particles Inclusions Nucleic Acid Vector Features Members in this Handbook AMV Alfalfa mosaic Baciliform 4 + ssRNA Aphid Alfalfa mosaic virus virus (nonpersistent) Bromovirus Brome mosiac Isosahedral 3 + ssRNA Some beetle virus crystalline Carlavirus Carnation Flexous 1 + ssRNA Aphid Narrow Blackberry calico virus latent virus rod various types (nonpersistent) host range Lily symptomless virus Blueberry scorch virus Potato virus M Potato virus S Caulimovirus Cauliflower Isometric 1 + dsDNA Aphid Narrow Blueberry red ringspot mosaic virus (nonpersistent) host range virus Dahlia nosaic virus Strawberry vein-banding virus Closterovirus Beet yellows Filamen- 1 + ssRNA Aphid Beet yellows virus virus tous rod in phloem (semipersistent) Comovirus Cowpea Isometric 2 + ssRNA Beetle Narrow mosaic virus vacuolate and host range crystalloid Cucumovirus Cucumber Isometric 3 + sRNA Aphid Cucumber mosaic virus mosaic virus in mesophyll (nonpersistent), Sap Dianthovirus Carnation Isometric 2 + ssRNA ringspot virus Enamovirus Pea enation Isometric 2 + ssRNA Aphid Pea enation mosaic virus mosaic virus in phloem (persistent) Geminivirus Maize streak Double 1 + ssDNA Beet curly top virus virus particle in phloem Hordeivirus Barley stripe Rod 3 ssRNA Barley stripe mosaic virus mosaic Ideaovirus Raspberry Isometric 3 ssRNA Pollen Raspberry bushy dwarf bushy dwarf virus virus Ilarvirus Tobacco Isometric 3 + ssRNA Pollen, Seed Apple mosaic virus streak virus (transmission Blueberry shock ilarvirus mediated -

Automatic Detection of Tulip Breaking Virus (TBV) in Tulip Fields Using Machine Vision

Automatic detection of tulip breaking virus (TBV) in tulip fields using machine vision Gerrit Polder1*, Gerie W.A.M. van der Heijden1, 2 2 Joop van Doorn , Ton A.H.M.C. Baltissen 1Biometris, Wageningen University, PO Box 100, Wageningen, 6700 AC The Netherlands 2Applied Plant Research, Wageningen University, PO Box 85, 2160 AB Lisse, The Netherlands *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Tulip breaking virus (TBV) causes severe economic losses for the Netherlands. Infected plants must be removed from the field as soon as possible to prevent further spread by aphids. Until now screening is done by visual inspection in the field. As the availability of human experts is limited there is an urgent need for a rapid, automated and objective method of screening. Based on laboratory experiments in 2008, we developed a vision method for use in the open field. From 2009 – 2011 field trials were carried out and the techniques were tested and improved. The final score of our system in the last experiment (2011) approached the scores obtained by the human crop experts. Key words: Plant virus, Image processing, Autonomous robot. 1. Introduction Tulip and other bulbous ornamental crops are often infected by viruses. One of the most important viruses in tulips is the potyvirus TBV (tulip breaking virus). Symptoms of the virus can manifest themselves in different ways, including striping of the leaves and abnormal flowers (Dekker et al. 1993). The presence of viruses causes a reduction in the quantity and quality of the product, which leads to sales and export restrictions. -

Symptoms of Virus Diseases in Plants L

SYMPTOMS OF VIRUS DISEASES IN PLANTS WITH INDEXES OF NAMES OF SYMPTOMS IN ENGLISH, DUTCH, GERMAN, FRENCH, ITALIAN, AND SPANISH L. BOS RESEARCH INSTITUTE FOR PLANT PROTECTION, WAGENINGEN, THE NETHERLANDS Contents Preface 7 Introduction 9 definition and significance of symptoms 10 nomenclature of symptoms 11 Pathogenesis 12 definition of disease ' 12 origin of symptoms 13 sequence of symptoms 20 plants may fight back 27 absence of symptoms 30 variation of symptoms 36 Description of symptoms 40 biochemical and metabolic changes 41 anatomical deviations 48 growth reduction 54 . ••'lour deviations 56 in leaves 57 in stems 68 in flowers 70 infruits and seeds 72 water deficiency 73 necrosis 75 in leaves 75 in stems 77 infruits and seeds 84 abnormal cork formation 85 malformations 87 secondary malformations . .' 87 primary malformations 91 witches' broom phenomena 104 miscellaneous abnormalities 113 increased predisposition to non-viral diseases 117 virus particles and inclusion bodies 119 visualization of virusparticles 120 intracellular inclusions 122 submicroscopic virus aggregates andnon-aggregated particles . 138 Deviations resembling symptoms of virusdisease s 144 genetic aberrations 144 physiological non-parasitic disturbances 146 insect toxaemias 147 disorders due to pathogenic micro-organisms 149 multicausal abnormalities 151 Retrospect 152 References 154 Index of nameso f symptoms 183 English index with Dutch, German, French, Italian and Spanish equivalents 183 Dutch index of names of symptoms 198 German index of names of symptoms 201 French index of names of symptoms 205 Italian index of names of symptoms 208 Spanish index of names of symptoms 211 Subject index 215 Preface to the thirdeditio n It was a pleasure to hear sosoo n from the publisher that this book on such a specialized subject as symptoms of virus diseases needed another edition. -

Bulletin 46 (1) Corrected.Cdr

Contents Table des Matières The CanadianBotanical President’s Message Page 1 AssociationBulletin Association News Page 3 News from the Sections Page 7 Bulletin de l’Association Graduate Student Profiles Page 9 Botanique du Canada March/Mars 2013. Volume 46 No.1/No1 A Tribute for Laurie Consaul Message du Président by Lynn Gillespie Page 10 On pourrait douter de l'arrivée du printemps alors que le vent plein de grésil et de neige frappe à nos fenêtres. Cependant, je sais qu'il arrive car il y a de la fièvre dans l'air. Plusieurs membres de l'Association sont occupés à préparer la réunion annuelle. L'évènement est organisé avec les plus grands soins par le comité de Kamloops, et par les directeurs de section qui ont invités de superbes scientifiques pour participer aux colloques. Frédérique Guinel Major Invasive Alien Plants Des courriels ont été échangés, des décisions ont été prises, et les plans vont de of Natural Habitats in l'avant. Cette année, il y aura un colloque spécial coparrainé par les Éditions Canada Sciences Canada (voir l'article de Kelly Bogh p.3) et l'ABC / CBA. Il s'adresse à 6. European Frog-bit l'ensemble des membres et mettra l'accent sur la biologie des arbres. Avec l'aide de Paul M. Catling and tous les directeurs de section, j'ai pu inviter des scientifiques reconnus, et chacun d'eux discutera des arbres à sa manière. Le colloque se terminera par une Gisèle Mitrow discussion à laquelle participeront les orateurs. Je suis impatiente de participer à Page 13 notre réunion annuelle et je vous invite tous à venir nous rejoindre.