Lami Town Cities and Climate Change Initiative Vulnerability and Adaptation Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Central Division

THE FOLLOWING IS THE PROVISIONAL LIST OF POLLING VENUES AS AT 3IST DECEMBER 2017 CENTRAL DIVISION The following is a Provisional List of Polling Venues released by the Fijian Elections Office FEO[ ] for your information. Members of the public are advised to log on to pvl.feo.org.fj to search for their polling venues by district, area and division. DIVISION: CENTRAL AREA: VUNIDAWA PRE POLL VENUES -AREA VUNIDAWA Voter No Venue Name Venue Address Count Botenaulu Village, Muaira, 1 Botenaulu Community Hall 78 Naitasiri Delailasakau Community Delailasakau Village, Nawaidi- 2 107 Hall na, Naitasiri Korovou Community Hall Korovou Village, Noimalu , 3 147 Naitasiri Naitasiri Laselevu Village, Nagonenicolo 4 Laselevu Community Hall 174 , Naitasiri Lomai Community Hall Lomai Village, Nawaidina, 5 172 Waidina Naitasiri 6 Lutu Village Hall Wainimala Lutu Village, Muaira, Naitasiri 123 Matainasau Village Commu- Matainasau Village, Muaira , 7 133 nity Hall Naitasiri Matawailevu Community Matawailevu Village, Noimalu , 8 74 Hall Naitasiri Naitasiri Nabukaluka Village, Nawaidina ELECTION DAY VENUES -AREA VUNIDAWA 9 Nabukaluka Community Hall 371 , Naitasiri Nadakuni Village, Nawaidina , Voter 10 Nadakuni Community Hall 209 No Venue Name Venue Address Naitasiri Count Nadovu Village, Muaira , Nai- Bureni Settlement, Waibau , 11 Nadovu Community Hall 160 1 Bureni Community Hall 83 tasiri Naitasiri Naitauvoli Village, Nadara- Delaitoga Village, Matailobau , 12 Naitauvoli Community Hall 95 2 Delaitoga Community Hall 70 vakawalu , Naitasiri Naitasiri Nakida -

Mainstreaming Adaptation to Climate Change Sofia Bettencourt, World Bank

Mainstreaming Adaptation to Climate Change in Pacific Island Economies Sofia Bettencourt, World Bank Pacific Islands Vulnerability is Rising... Event Year Country Losses ( US$ million) Cyclone Ofa 1990 Samoa 140 Cyclone Val 1991 Samoa 300 Typhoon Omar 1992 Guam 300 Cyclone Kina 1993 Fiji 140 Cyclone Martin 1997 Cook Islands 7.5 Cyclone Hina 1997 Tonga 14.5 Drought 1997 Regional >175 Cyclone Cora 1998 Tonga 56 Cyclone Dani 1999 Fiji 3.5 Sources: Campbell (1999) and World Bank (2000) The costs of extreme weather events in the 1990s exceeded US$1 billion Support Projects 2003 Adaptation Projects 2002 Donor Commitments are also rising… 2001 $4,000 Risk/Disaster Years $3,500 2000 Manag ement $3,000 $2,500 $2,000 1999 $1,500 $1,000 daptation Consultation, Fiji 2003 $500 $0 Commitments (US$’000) Commitments Source: Second High Level A Emerging Key Principles Merge adaptation and hazard management Treat adaptation as a major economic, social and environmental risk Mainstream adaptation into national economic planning House adaptation in a high-level coordinating Ministry Treat adaptation as a long-term process Involve communities and private sector Disseminate information to high-level decision makers and the public Strengthen regulations affecting vulnerability An Example of Mainstreaming The Kiribati Adaptation Program Kiribati Source: http://www.infoplease.com/atlas/country/kiribati.html Kiribati is one of the Most Vulnerable Countries in the World in its Physical Environment… The 33 atolls of Kiribati are less than 500-1,000 meters -

Pacific Economic Monitor, December 2013

THE ECONOMIC SETTING 1 BUDGET ANALYSIS December 2013 www.adb.org/pacmonitor The Monitor provides an update of Highlights developments in Pacific economies and Weak global growth is impacting the Pacific largely through lower explores topical policy issues. commodity prices. Fiscal consolidation in the United States (US) and moderating growth in developing economies has slowed growth in the CONTENTS world economy in 2013. Subdued global demand is keeping international Highlights 1 commodity prices low—adversely affecting agriculture, mineral, and The economic setting 3 forestry export earnings of some Pacific economies. The moderation in growth in the People’s Republic of China (PRC) is expected to dampen the Country economic updates 5 outlook for Australia, with possible flow through effects on the Pacific. Policy briefs: Strong revenue performance in smaller Pacific economies has Economics of climate change 18 continued in 2013, while larger economies have struggled. For the second consecutive year, fishing license revenues are exceeding budget Economic indicators 32 targets in Kiribati, the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI), Nauru, and Tuvalu due to rising rates under a regional vessel day scheme. Tax How to reach us collections in the Cook Islands, Fiji, and Vanuatu are also higher than [email protected] expected. In contrast, revenue collections in the large resource exporters of the Pacific are weakening. Revenues from the mineral and petroleum Asian Development Bank sectors are below budgeted levels in Papua New Guinea (PNG), while Pacific Department declining production in major offshore fields is resulting in lower Apia Level 6 Central Bank of Samoa Bldg. petroleum revenue in Timor-Leste. -

Social Policy in the Post-Crisis Context of Small Island Developing States: a Synthesis

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Perch, Leisa; Roy, Rathin Working Paper Social policy in the post-crisis context of small island developing states: A synthesis Working Paper, No. 67 Provided in Cooperation with: International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth (IPC-IG) Suggested Citation: Perch, Leisa; Roy, Rathin (2010) : Social policy in the post-crisis context of small island developing states: A synthesis, Working Paper, No. 67, International Policy Centre for Inclusive Growth (IPC-IG), Brasilia This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/71774 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in -

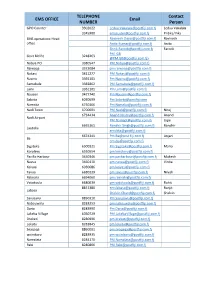

EMS Operations Centre

TELEPHONE Contact EMS OFFICE Email NUMBER Person GPO Counter 3302022 [email protected] Ledua Vakalala 3345900 [email protected] Pritika/Vika EMS operations-Head [email protected] Ravinesh office [email protected] Anita [email protected] Farook PM GB Govt Bld Po 3218263 @[email protected]> Nabua PO 3380547 [email protected] Raiwaqa 3373084 [email protected] Nakasi 3411277 [email protected] Nasinu 3392101 [email protected] Samabula 3382862 [email protected] Lami 3361101 [email protected] Nausori 3477740 [email protected] Sabeto 6030699 [email protected] Namaka 6750166 [email protected] Nadi Town 6700001 [email protected] Niraj 6724434 [email protected] Anand Nadi Airport [email protected] Jope 6665161 [email protected] Randhir Lautoka [email protected] 6674341 [email protected] Anjani Ba [email protected] Sigatoka 6500321 [email protected] Maria Korolevu 6530554 [email protected] Pacific Harbour 3450346 [email protected] Mukesh Navua 3460110 [email protected] Vinita Keiyasi 6030686 [email protected] Tavua 6680239 [email protected] Nilesh Rakiraki 6694060 [email protected] Vatukoula 6680639 [email protected] Rohit 8812380 [email protected] Ranjit Labasa [email protected] Shalvin Savusavu 8850310 [email protected] Nabouwalu 8283253 [email protected] -

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents

Setting Priorities for Marine Conservation in the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion Contents Acknowledgements 1 Minister of Fisheries Opening Speech 2 Acronyms and Abbreviations 4 Executive Summary 5 1.0 Introduction 7 2.0 Background 9 2.1 The Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 9 2.2 The biological diversity of the Fiji Islands Marine Ecoregion 11 3.0 Objectives of the FIME Biodiversity Visioning Workshop 13 3.1 Overall biodiversity conservation goals 13 3.2 Specifi c goals of the FIME biodiversity visioning workshop 13 4.0 Methodology 14 4.1 Setting taxonomic priorities 14 4.2 Setting overall biodiversity priorities 14 4.3 Understanding the Conservation Context 16 4.4 Drafting a Conservation Vision 16 5.0 Results 17 5.1 Taxonomic Priorities 17 5.1.1 Coastal terrestrial vegetation and small offshore islands 17 5.1.2 Coral reefs and associated fauna 24 5.1.3 Coral reef fi sh 28 5.1.4 Inshore ecosystems 36 5.1.5 Open ocean and pelagic ecosystems 38 5.1.6 Species of special concern 40 5.1.7 Community knowledge about habitats and species 41 5.2 Priority Conservation Areas 47 5.3 Agreeing a vision statement for FIME 57 6.0 Conclusions and recommendations 58 6.1 Information gaps to assessing marine biodiversity 58 6.2 Collective recommendations of the workshop participants 59 6.3 Towards an Ecoregional Action Plan 60 7.0 References 62 8.0 Appendices 67 Annex 1: List of participants 67 Annex 2: Preliminary list of marine species found in Fiji. 71 Annex 3 : Workshop Photos 74 List of Figures: Figure 1 The Ecoregion Conservation Proccess 8 Figure 2 Approximate -

Logistics Capacity Assessment VANUATU

LCA - <VANUATU> Version 1.07,5 Logistics Capacity Assessment VANUATU Country Name VANUATU Official Name REPUBLIC of VANUATU Assessment Assessment Dates: From 19th January 2011 To 31st March 2011 Name of Assessor Florent Chané Title & Position Logistics Consultant Email contact [email protected] 1/106 LCA - <VANUATU> Version 1.07,5 1. Table of Contents 1. Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................................................... 2 2. Country Profile .................................................................................................................................................................... 3 2.1. Introduction & Background ....................................................................................................................................... 3 2.2. Humanitarian Background ........................................................................................................................................ 5 2.3. National Regulatory Departments/Bureau and Quality Control/Relevant Laboratories ...................................... 11 2.4. Customs Information ............................................................................................................................................... 11 3. Logistics Infrastructure ..................................................................................................................................................... 35 3.1. Port Assessment -

Shelter and Settlements Risk Profile NATURAL DISASTERS from 1980

Shelter and Settlements Risk Profile ShelterCluster.org Coordinating Humanitarian Shelter HISTORIC EVENTS (ReliefWeb) Dec 2012 1. Tropical Cyclone Evan KEY DEVELOPMENT INDICATORS Tropical Cyclone Evan (TC Evan) − a Category 4 cyclone, wind Full Name: Republic Of The Fiji Islands speeds of 210 km/h (130 mph), impacted Northern Vanua Population: 862,333 (UN, 2012) Levu and Western Viti Levu on 17 December 2012,is Annual Growth Rate: 0.5% considered one of the worst to ever hit Fiji in recent history. Capital: Suva Approximately 60% of the total population were affected in Population In Urban Areas: 52.90% the post-disaster period. The Northern division recorded the Area: 18,376 Sq Km(7,095 Sq.mile) highest percentage of affected population (52%) as a Major Languages: English, Fijian, Hindi proportion of their total population, followed by the Western Division (38%) and the Central and Eastern divisions (23%). Major Religions: Christianity, Hinduism, Islam March 2. Fiji: Floods Life Expectancy: (UN) 67 Years (M)/72 Years (W) 2012 Monetary Unit: 1 Fijian Dollar = 100 Cents Severe flooding in the areas of Ra, Tavua, Ba, Lautoka, Nadi, Main Exports: Sugar, Clothing, Gold, Processed Nadroga, Sigatoka, and Rewa in January 2012 The Fish, Timber Government of Fiji estimated that damage from the 2012 GNI Per Capita: US $3,720 (WB) 5,390 (FS) floods was at approximately F$71 million. This suggests that Human Development Index: 0.6881 Fiji experienced damage of F$146 million in 2012 alone. Rainfall In Capital (Mm): 3040 Jan 3. Fiji: Floods Temperature In Capital City ° C: 22.2/28.7 2012 Average Family Size: 5 March 4. -

Domestic Air Services Domestic Airstrips and Airports Are Located In

Domestic Air Services Domestic airstrips and airports are located in Nadi, Nausori, Mana Island, Labasa, Savusavu, Taveuni, Cicia, Vanua Balavu, Kadavu, Lakeba and Moala. Most resorts have their own helicopter landing pads and can also be accessed by seaplanes. OPERATION OF LOCAL AIRLINES Passenger per Million Kilometers Performed 3,000 45 40 2,500 35 2,000 30 25 1,500 International Flights 20 1,000 15 Domestic Flights 10 500 5 0 0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Revenue Tonne – Million KM Performed 400,000 4000 3500 300,000 3000 2500 200,000 2000 International Flights 1500 100,000 1000 Domestic Flights 500 0 0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Principal Operators Pacific Island Air 2 x 8 passenger Britton Norman Islander Twin Engine Aircraft 1 x 6 passenger Aero Commander 500B Shrike Twin Engine Aircraft Pacific Island Seaplanes 1 x 7 place Canadian Dehavilland 1 x 10 place Single Otter Turtle Airways A fleet of seaplanes departing from New Town Beach or Denarau, As well as joyflights, it provides transfer services to the Mamanucas, Yasawas, the Fijian Resort (on the Queens Road), Pacific Harbour, Suva, Toberua Island Resort and other islands as required. Turtle Airways also charters a five-seater Cessna and a seven-seater de Havilland Canadian Beaver. Northern Air Fleet of six planes that connects the whole of Fiji to the Northern Division. 1 x Britten Norman Islander 1 x Britten Norman Trilander BN2 4 x Embraer Banderaintes Island Hoppers Helicopters Fleet comprises of 14 aircraft which are configured for utility operations. -

Human Activities and Flood Hazards and Risks in the South West Pacific: a Case Study of the Navua Catchment Area, Fiji Islands

HUMAN ACTIVITIES AND FLOOD HAZARDS AND RISKS IN THE SOUTH WEST PACIFIC: A CASE STUDY OF THE NAVUA CATCHMENT AREA, FIJI ISLANDS Katalaine Duaibe A thesis submitted to Victoria University of Wellington in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Science in Physical Geography School of Geography, Environment and Earth Science Victoria University of Wellington 2008 Abstract Human activity is increasingly becoming a factor contributing to ‘disasters’ that occur worldwide. As evident in the Asian Tsunami of 2004, the high levels of loss of life and livelihood, and damage to property were largely due to the population density and human development of the physical landscape of the stricken region. The magnitude of natural hazards coupled with the high population density and low levels of development can have disastrous or catastrophic impacts on a nation as a whole, especially in small island states. Furthermore, the lack of governance structures, legislative compliance, and regulatory land use and planning coupled with the perception of risk of the general public, can all contribute to the magnitude of disasters. The flood plains of Navua, a small rural town outside of Fiji’s capital and prone to all types of flooding, are explored to determine the extent to which human activities impact on the magnitude of flooding and flood damage. Human activities such as land degradation, deforestation of catchment areas, increased population density along the Navua riverbanks inadequate land use planning, zoning, and control of flood plain development; and inadequate drainage, and management of discharges are examined when determining the factors that have contributed to the increased incidence of flooding of the past 100 years until 2004. -

4348 Fiji Planning Map 1008

177° 00’ 178° 00’ 178° 30’ 179° 00’ 179° 30’ 180° 00’ Cikobia 179° 00’ 178° 30’ Eastern Division Natovutovu 0 10 20 30 Km 16° 00’ Ahau Vetauua 16° 00’ Rotuma 0 25 50 75 100 125 150 175 200 km 16°00’ 12° 30’ 180°00’ Qele Levu Nambouono FIJI 0 25 50 75 100 mi 180°30’ 20 Km Tavewa Drua Drua 0 10 National capital 177°00’ Kia Vitina Nukubasaga Mali Wainingandru Towns and villages Sasa Coral reefs Nasea l Cobia e n Pacific Ocean n Airports and airfields Navidamu Labasa Nailou Rabi a ve y h 16° 30’ o a C Natua r B Yanuc Division boundaries d Yaqaga u a ld Nabiti ka o Macuata Ca ew Kioa g at g Provincial boundaries Votua N in Yakewa Kalou Naravuca Vunindongoloa Loa R p Naselesele Roads u o Nasau Wailevu Drekeniwai Laucala r Yasawairara Datum: WGS 84; Projection: Alber equal area G Bua Bua Savusavu Laucala Denimanu conic: standard meridan, 179°15’ east; standard a Teci Nakawakawa Wailagi Lala w Tamusua parallels, 16°45’ and 18°30’ south. a Yandua Nadivakarua s Ngathaavulu a Nacula Dama Data: VMap0 and Fiji Islands, FMS 16, Lands & Y Wainunu Vanua Levu Korovou CakaudroveTaveuni Survey Dept., Fiji 3rd Edition, 1998. Bay 17° 00’ Nabouwalu 17° 00’ Matayalevu Solevu Northern Division Navakawau Naitaba Ngunu Viwa Nanuku Passage Bligh Water Malima Nanuya Kese Lau Group Balavu Western Division V Nathamaki Kanacea Mualevu a Koro Yacata Wayalevu tu Vanua Balavu Cikobia-i-lau Waya Malake - Nasau N I- r O Tongan Passage Waya Lailai Vita Levu Rakiraki a Kade R Susui T Muna Vaileka C H Kuata Tavua h E Navadra a Makogai Vatu Vara R Sorokoba Ra n Lomaiviti Mago -

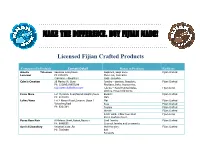

Make the Difference. Buy Fijian Made! ……………………………………………………….…

…….…………………………………………………....…. MAKE THE DIFFERENCE. BUY FIJIAN MADE! ……………………………………………………….…. Licensed Fijian Crafted Products Companies/Individuals Contact Detail Range of Products Emblems Amelia Yalosavu Sawarua Lokia,Rewa Saqamoli, Saqa Vonu Fijian Crafted Lesumai Ph:8332375 Mua i rua, Ramrama (Sainiana – daughter) Saqa -gusudua Cabe’s Creation 20 Marino St, Suva Jewelry - earrings, Bracelets, Fijian Crafted Ph: 3318953/9955299 Necklace, Belts, Accessories. [email protected] Fabrics – Hand Painted Sulus, Fijian Sewn Clothes, Household Items Finau Mara Lot 15,Salato Road,Namdi Heights,Suva Baskets Fijian Crafted Ph: 9232830 Mats Lolive Vana Lot 2 Navani Road,Suvavou Stage 1 Mat Fijian Crafted Votualevu,Nadi Kuta Fijian Crafted Ph: 9267384 Topiary Fijian Crafted Wreath Fijian Crafted Patch work- Pillow Case Bed Fijian Sewn Sheet Cushion Cover. Paras Ram Nair 6 Matana Street,Nakasi,Nausori Shell Jewelry Fijian Crafted Ph: 9049555 Coconut Jewelry and ornaments Seniloli Jewellery Veiseisei,Vuda ,Ba Wall Hanging Fijian Crafted Ph: 7103989 Belt Pendants Makrava Luise Lot 4,Korovuba Street,Nakasi Hand Bags Fijian Crafted Ph: 3411410/7850809 Fans [email protected] Flowers Selai Buasala Karova Settlement,Laucala bay Masi Fijian Crafted Ph:9213561 Senijiuri Tagi c/-Box 882, Nausori Iri-Buli Fijian Crafted Vai’ala Teruka Veisari Baskets, Place Mats Fijian Crafted Ph:9262668/3391058 Laundary Baskets Trays and Fruit baskets Jonaji Cama Vishnu Deo Road, Nakasi Carving – War clubs, Tanoa, Fijian Crafted PH: 8699986 Oil dish, Fruit Bowl Unik