Africa Census Processing Handbook – II. Editing Handbook, page 38

II. Africa Census Editing Handbook

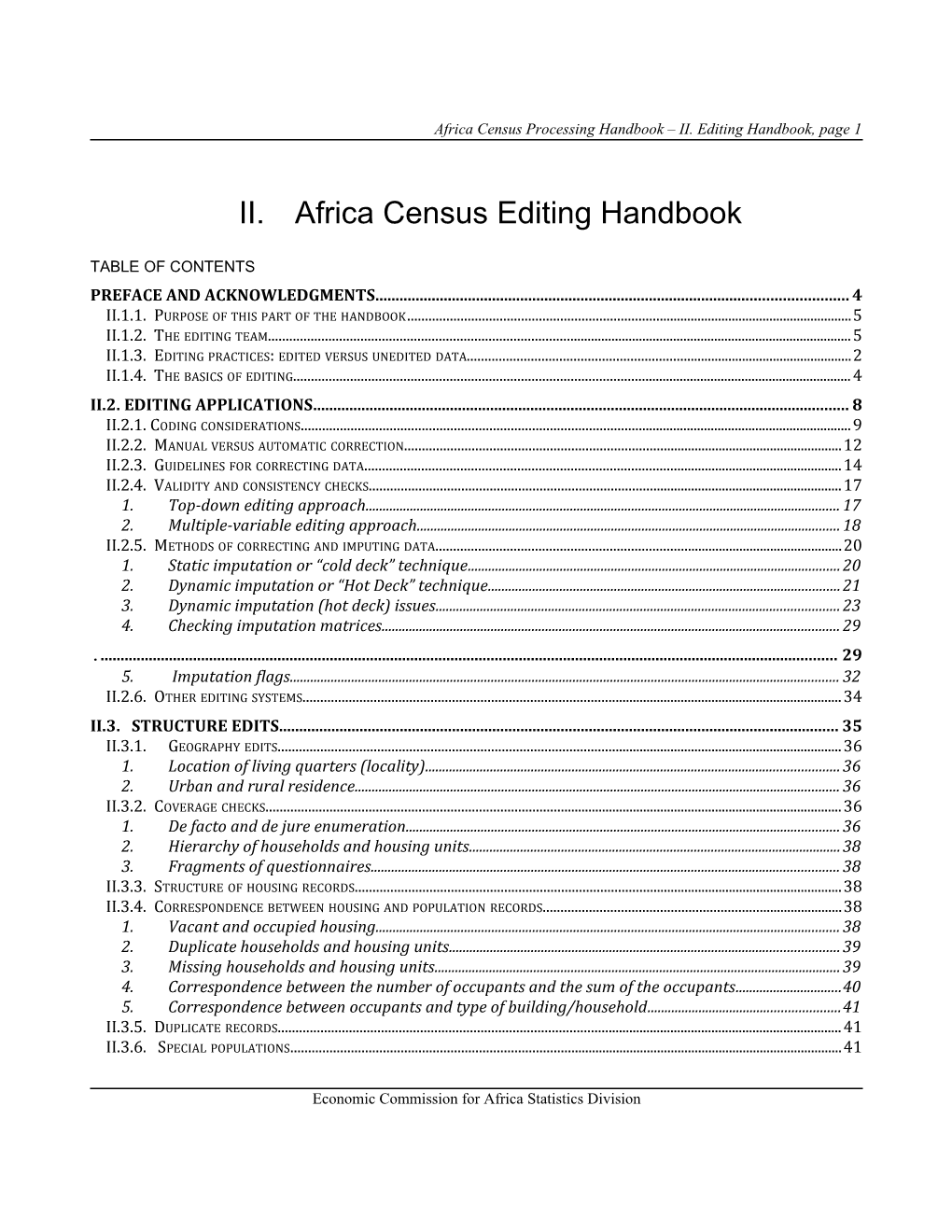

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS 4

II.1.1. Purpose of this part of the handbook 5

II.1.2. The editing team 5

II.1.3. Editing practices: edited versus unedited data 2

II.1.4. The basics of editing 4

II.2. EDITING APPLICATIONS 8

II.2.1. Coding considerations 9

II.2.2. Manual versus automatic correction 12

II.2.3. Guidelines for correcting data 14

II.2.4. Validity and consistency checks 17

1. Top-down editing approach 17

2. Multiple-variable editing approach 18

II.2.5. Methods of correcting and imputing data 20

1. Static imputation or “cold deck” technique 20

2. Dynamic imputation or “Hot Deck” technique 21

3. Dynamic imputation (hot deck) issues 23

4. Checking imputation matrices 29

. 29

5. Imputation flags 32

II.2.6. Other editing systems 34

II.3. STRUCTURE EDITS 35

II.3.1. Geography edits 36

1. Location of living quarters (locality) 36

2. Urban and rural residence 36

II.3.2. Coverage checks 36

1. De facto and de jure enumeration 36

2. Hierarchy of households and housing units 38

3. Fragments of questionnaires 38

II.3.3. Structure of housing records 38

II.3.4. Correspondence between housing and population records 38

1. Vacant and occupied housing 38

2. Duplicate households and housing units 39

3. Missing households and housing units 39

4. Correspondence between the number of occupants and the sum of the occupants 40

5. Correspondence between occupants and type of building/household 41

II.3.5. Duplicate records 41

II.3.6. Special populations 41

1. Persons in collectives 41

2. Groups Difficult to Enumerate 42

II.3.7. Determining head of household and spouse 44

1. Editing the head of household variable 44

2. Editing the spouse 47

II.3.8. Age and birth date 48

II.3.9. Counting invalid entries 49

II.4. EDITS FOR POPULATION ITEMS 49

II.4.1. Demographic characteristics 50

1. Relationship 51

2. Sex 53

3. Birth date and age 56

4. Marital status 61

5. Age at first marriage 64

6. Fertility: children ever born and children surviving 65

These tests would normally be run first. Once the program determines that all three pieces of information are valid and consistent, the edit is finished. See below for an example. 69

8. Fertility: age at first birth 75

9. Mortality 75

10. Maternal or paternal orphanhood (P5G) and mother’s line number 77

B. Migration characteristics 78

1. Place of birth 78

2. Citizenship 80

3. Duration of residence 82

4. Place of previous residence 83

5. Place of residence at a specified date in the past 84

6. Year of Arrival 84

7. Relationship of Duration of Residence to Year of Arrival 86

7. Usual Residence 86

C. Social characteristics 86

1. Ability to read and write (literacy) 87

2. School attendance 87

3. Educational attainment (highest grade or level completed) 88

4. Field of education and educational qualifications 89

5. Religion 90

6. Language 91

7. Ethnicity and Indigenous peoples 92

8. Disability 94

II.4.4. Economic characteristics 95

1. Activity status 95

(a) Paid employment. Paid employment is of two types: 95

(b) Self-employment. Self employment is also of two types: 96

The edits for “not currently active” have been incorporated into the above edits for economic activity. 97

2. Time worked. 99

3. Occupation. 99

4. Industry. 100

5. Status in employment. 101

6. Income 102

7. Institutional sector 103

8. Employment in the Informal Sector 103

if INFORMAL_SECTOR in 1:2 then {whether working in informal sector known} 103

9. Place of work 103

II.6. HOUSING EDITS 104

C. Occupied and vacant housing units 119

II.7 DERIVED VARIABLES 119

A. Derived variables for housing records 120

B. Derived variables for population records 127

1. Economic Activity Status or Economic Status Recode (ESR) 127

Economically active 127

CONCLUSIONS 134

PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This document has been written as part of collaboration with the Economic Commission for Africa’s Statistics Division’s interest in providing guidelines for Africa’s National Statistical Offices as they develop their Data Capture, Editing, and Tabulation and Dissemination procedures. Statistics South Africa developed the initial first volume on Data Capture which was expanded afterwards as the Africa Census Data Capture Handbook. This second volume covers census editing as the Africa Census Editing Handbook, and will include actual edits from previous African censuses as illustration. A third volume covers tabulation, dissemination, analysis, and archiving. Every effort has been made to include “real” examples from African country edits. As will be seen, not all countries use all edits based on the items in the UN Principles and Recommendations, and, in some cases, none of the countries cited could provide an edit to illustrate a particular Recommendation. It is useful to note that while all of the examples here are from African countries (or, in a few cases from the US Bureau’s Popstan); these tables should also be of interest to Pacific Islands and Caribbean countries, among others.

Michael J. Levin, Senior Census Trainer, Harvard Center for Population and Development wrote this version of the document. Anthony Matovu, Uganda Bureau of Statistics and Steven Lwendo, Harvard University, contributed to earlier versions of the document.

This document is in draft and does not represent the position of the Economic Commission for Africa’s Statistics Division. The document is being distributed – in draft – to elicit comments, corrections, and suggestions for improvement. Since it is the first document of this sort to be developed, it is definitely a work in progress.

II.1. INTRODUCTION

Economic Commission for Africa Statistics Division

Africa Census Processing Handbook – II. Editing Handbook, page 38

Economic Commission for Africa Statistics Division

Africa Census Processing Handbook – II. Editing Handbook, page 38

II.1.1. Purpose of this part of the handbook

A well-designed census or survey[1], with minimal errors in the final product, is an invaluable resource for a nation. To obtain accurate census or survey results data must be free, to the greatest extent possible, from errors and inconsistencies, especially after the data processing stage. The procedure for detecting errors in and between data records, during and after data collection and capture, and on adjusting individual items is known as population and housing census editing

No census or survey data are ever perfect. Countries have long recognized that data from censuses and surveys have problems, so have adopted various approaches for dealing with data gaps and inconsistent responses. However, because of the long interval between censuses, the procedures that were used to edit the data are often not properly documented. Hence, countries have to reinvent the process used in earlier data collection activities for a new census or survey.

Every Census Editing Process should: (1) give users high quality census data; (2) identify the types and sources of error; and (3) provide adjusted census results. If the census editing process achieves these three goals – goals that we will stress throughout this handbook, the census editing will have been successful.

The African Census Editing Handbook is designed to bridge this gap in census and survey data editing methodology and to provide information for officials on the use of various approaches to census editing. It is also intended to encourage countries to retain a history of their editing experiences, enhance communication between subject-matter and data processing specialists, and document the activities carried out during the current census or survey in order to avoid duplication of effort in the future.

The Handbook is a reference for both subject-matter [2] and data processing specialists as they work as teams to develop editing specifications and programs for censuses and surveys. It follows a “cookbook” approach, which permits countries to adopt the edits most appropriate for their own country’s current statistical situation. The present publication is also designed to promote better communication between these specialists as they develop and implement their editing programme.

II.1.2. The editing team

As national statistical offices prepare for a census, they need to consider a variety of potential improvements to the quality of their work. One of these is the creation of an editing team. The editing process should be the responsibility of an editing team that includes census managers, subject-matter specialists and data processors. This team should be set up as soon as preparations for the census begin, preferably during the drafting of the questionnaire. The editing team is important from the beginning, and remains so throughout the editing process. Care in putting together the team and in developing and implementing the editing and imputation rules assures a census that is faster and more efficient.

Meetings between census officials and the user community concerning tabulations and other data products can provide insight into the edits that need to be performed. Frequently, users request a particular table or type of tables, that requires extra editing to eliminate potential inconsistencies. The editing team should plan to implement these tables during the initial editing period rather than implementing them at special tables after census processing. Developing the editing rules and the computer programs during a pretest or dress rehearsal makes it possible to test the programs themselves and leads to faster turn-around times for various parts of the editing and imputation process. The editing team then ascertains the impact of these various processes and takes remedial action if necessary.

Subject-matter and data processing specialists should work together to develop the editing and imputation rules. The editing team elaborates an error scrutiny and editing plan early in the census preparations. The census or survey editing team creates written sets of consistency rules and corrections.

In addition to developing the editing and imputation rules, the subject-matter and data processing specialists must work together at all stages of the census or survey, including during the analysis. The risk of doing too much editing is as great as the risk of doing too little editing and having unedited or spurious information in the dataset. Hence, both groups must take responsibility to maintain their metadatabases properly. The editing team must also use available administrative sources and survey registers efficiently in order to improve subsequent census or survey operations.

Communication between subject-matter and data processing specialists was limited when national statistical/census offices used mainframe computers. This division continued for some time after the advent of microcomputers, but computer program packages have become more user-friendly, and now many subject-matter personnel can actually develop and test their own tabulation plans and edits. While subject-matter specialists usually do not process the data, they often understand the steps the data processing specialists take to process the data.

II.1.3. Editing practices: edited versus unedited data

Countries perform census edits to improve the data and its presentation. In this section, the Handbook highlights a problem facing national census/statistical offices when unedited census data is released. The issues are illustrated using a hypothetical set of data.

The national census/statistical office of a fictional country faces the dilemma of trying to serve multiple users. Some users may want unknown entries included for analysis or research and some others may want data with minimum noise (possible error) for their planning or policy purposes. If the national census/statistical office disseminates an unedited table, such as that on the left side of table 1, both the analysts and the policy makers will have to make assumptions when using the data. Table 1 illustrates this point with only a small number of persons. It shows that for 23 persons in this country sex[3] was not reported and for 15 age was not reported. These omissions may have resulted from non-responses or from keying errors. Of these, two cases reported neither sex nor age.

Economic Commission for Africa Statistics Division

Africa Census Processing Handbook – II. Editing Handbook, page 38

Table 1. Sample population by 15-year age group and sex, using unedited and edited data

Unedited data / Edited dataAge group / Total / Male / Female / Not reported / Total / Male / Female

Total / 4,147 / 2,033 / 2,091 / 23 / 4,147 / 2,045 / 2,102

Less than 15 years / 1,639 / 799 / 825 / 15 / 1,743 / 855 / 888

15 to 29 years / 1,256 / 612 / 643 / 1 / 1,217 / 603 / 614

30 to 44 years / 727 / 356 / 369 / 2 / 695 / 338 / 357

45 to 59 years / 360 / 194 / 166 / 0 / 341 / 182 / 159

60 to 74 years / 116 / 54 / 59 / 3 / 114 / 53 / 61

75 years and over / 34 / 12 / 22 / 0 / 37 / 14 / 23

Not reported / 15 / 6 / 7 / 2

Economic Commission for Africa Statistics Division

Africa Census Processing Handbook – II. Editing Handbook, page 38

Economic Commission for Africa Statistics Division

Africa Census Processing Handbook – II. Editing Handbook, page 38

Most users would make their own decisions about what to do with the unknowns. A logical, possibly naïve, approach would be to distribute the unknowns in the same proportion as the known values. If the national census/statistical office chooses to impute for the unknowns, the editing team may decide to have 12 males and 11 females, a figure that is about half-and-half, but skewed because the census enumerated more females. The results will then be consistent with the edited data shown on the right side of table 1.

Other options are available for handling the unknowns. For example, the editing team may decide to impute based on the sex distribution alone, ignoring other available information, such as the relationship between spouses, whether a person of unknown sex is reported as a mother of another person or whether a person of unknown sex has a positive entry for number of children ever born. An alternative imputation strategy would be to take one or more of these other variables into account.

Another alternative the national census/statistical office could choose would be to base the imputation on the age distribution. For sample population illustrated in table 1, a total of 15 cases occurred with unreported age. These data could also be distributed in the same proportions as the known values, again, a logical strategy for imputation. Still, the editing team could probably obtain better results by considering other variables and combinations, such as the relative age of husband and wife, of parent and child or grandparent and grandchild, or the presence of school age children, retirees and persons in the labour force.