Behavioral Finance, Decumulation and the Regulatory Strategy for Robo- Advice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities A Financial System That T OF EN TH M E A Financial System T T R R A E P A E S That Creates Economic Opportunities D U R E Y H T Nonbank Financials, Fintech, 1789 and Innovation Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation Nonbank Financials, Fintech, TREASURY JULY 2018 2018-04417 (Rev. 1) • Department of the Treasury • Departmental Offices • www.treasury.gov U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE TREASURY A Financial System That Creates Economic Opportunities Nonbank Financials, Fintech, and Innovation Report to President Donald J. Trump Executive Order 13772 on Core Principles for Regulating the United States Financial System Steven T. Mnuchin Secretary Craig S. Phillips Counselor to the Secretary T OF EN TH M E T T R R A E P A E S D U R E Y H T 1789 Staff Acknowledgments Secretary Mnuchin and Counselor Phillips would like to thank Treasury staff members for their contributions to this report. The staff’s work on the report was led by Jessica Renier and W. Moses Kim, and included contributions from Chloe Cabot, Dan Dorman, Alexan- dra Friedman, Eric Froman, Dan Greenland, Gerry Hughes, Alexander Jackson, Danielle Johnson-Kutch, Ben Lachmann, Natalia Li, Daniel McCarty, John McGrail, Amyn Moolji, Brian Morgenstern, Daren Small-Moyers, Mark Nelson, Peter Nickoloff, Bimal Patel, Brian Peretti, Scott Rembrandt, Ed Roback, Ranya Rotolo, Jared Sawyer, Steven Seitz, Brian Smith, Mark Uyeda, Anne Wallwork, and Christopher Weaver. ii A Financial System That Creates Economic -

Forum Participants

FORUM PARTICIPANTS David Blanchett Robin Diamonte Melissa Kahn Cristina Martin-Firvida Head of Retirement Research Chief Investment Officer Managing Director and Director, Financial Security Morningstar United Technologies Retirement Policy Strategist and Consumer Affairs Corporation State Street Global Advisors AARP Alison Borland Head of Defined Contribution Kenneth Forsythe Ray Kanner Lisa Massena Aon Hewitt AVP, Retirement Product Former Managing Director Executive Director Strategy & Ideation and CIO OregonSaves Ray Boshara Empower Retirement IBM Senior Adviser and Director Scott Matheson of the Center for Household Karen Friedman Michael Kiley Defined Contribution Practice Financial Stability Executive Vice President President Leader Federal Reserve Bank and Policy Director Plan Administrators, Inc. CAPTRUST Financial of St. Louis Pension Rights Center Advisors Gary Koenig Senior Fellow John Galateria Chris Mercer Aspen Institute Financial Vice President, Security Program Head of North America Financial Security Manager – Savings Plan Institutional AARP Public Policy Institute Verizon Anthony Bunnell Invesco James Lockhart Lew Minsky Chief Product Officer Diane Garnick Honest Dollar Vice Chairman President and CEO Managing Director and WL Ross & Co. LLC Defined Contribution Chip Castille Chief Income Strategist Institutional Investment Lori Lucas Managing Director, TIAA Association Executive Vice President Chief Retirement Strategist Fiona Greig and Defined Contribution Alicia Munnell BlackRock Director of Consumer Practice Leader Director, Center for Cindy Cattin Research Callan Associates Retirement Research JPMorgan Chase Institute Boston College Managing Director of Lathan Mahaffey Investment Operations Seth Harris Katherine Newman and Risk Management Executive Director, Head of Defined Contribution Exelon Attorney Provost and Senior Vice Seth Harris Law and Policy Investment Solutions Advisor Chancellor for Academic Harry Conaway Sales Affairs Catherine Harvey J.P. -

Malaysian Securities - Unlisted

MALAYSIAN SECURITIES - UNLISTED Bursa Malaysia Berhad As at 04 September 2019 Malaysian National Numbering Agency No. Company Malaysian ISIN 1 18M Enhanced Income Fund 1 MYU930000DL4 2 Aberdeen World Equity Fund MYU9000AG006 3 Aberdeen World Equity Fund (AUD Denominated) MYU9003AG000 4 Aberdeen Emerging Markets Corporate Bond Fund MYU9000AK008 5 Aberdeen Emerging Markets Corporate Bond Fund (USD Denominated) MYU9002AK004 6 Aberdeen Global Diversified Growth Fund MYU9000AJ000 7 Aberdeen Global Diversified Growth Fund (SGD Denominated) MYU9001AB005 8 Aberdeen Global Diversified Growth Fund (AUD Denominated) MYU9003AH008 9 Aberdeen Global Diversified Growth Fund (EURO Denominated) MYU9004AA001 10 Aberdeen Global Diversified Growth Fund (GBP denominated) MYU9005AH003 11 Aberdeen Global Diversified Growth Fund (USD Denominated) MYU9002AJ006 12 Aberdeen Indian Equity Fund - Class A MYU9000AI002 13 Aberdeen Indian Equity Fund - Class A (USD denominated) MYU9002AI008 14 Aberdeen Islamic Asia Pacific ex Japan Equity Fund - A Class MYU9000AH004 15 Aberdeen Islamic Asia Pacific ex Japan Equity Fund - A Class (USD Denominated) MYU9002AH000 16 Aberdeen Islamic Malaysia Equity Fund - A share MYU9000AC005 17 Aberdeen Islamic Malaysia Equity Fund - I share MYU9000AD003 18 Aberdeen Islamic World Equity Fund - A Share MYU9000AA009 19 Aberdeen Islamic World Equity Fund - A Share MYU9000AE001 20 Aberdeen Islamic World Equity Fund - A Share MYU9000AF008 21 Aberdeen Islamic World Equity Fund - A Share (AUD Denominated) MYU9003AA003 22 Aberdeen Islamic World -

Products, Tools and Strategies That Address Retirement Risks

Aging and Retirement Products, Tools, and Strategies that Address Retirement Risks - Essay Collection May 2020 Contents 1 Introduction 36 Tontine Savings Accounts Andrea Sellars and John Cutler Jonathan Barry Forman and Richard K. Fullmer 4 FIRST PRIZE: A Risk-Based Framework for Making 40 A Danish Perspective on Investment-Based Retirement Income Decisions Retirement Income: Innovative DC Retirement R. Evan Inglis Income Solutions From Denmark Per U.K. Linnemann 11 SECOND PRIZE: SeLFIES: A-New(-ity) Look for Retirement 45 Aromer: Solving the Catch-22 of the 401(k) Robert Merton, Arun Muralidhar, Paula Hogan Kalon McMahon 16 THIRD PRIZE: New Approaches to Communicating 50 Take Ownership of Your Retirement Process: to Workers About Pensions Oversight Tool to Understand Risks Yael Hadass, Marion Laboure, Sally Shen, John Max J. Rudolph Turner 57 Introducing the Total Benefit Account: A Single 21 Collective Defined Contribution: Time to Take Source of Employer Funding for Employee Needs Action Doug Spencer and Greg Ward Elizabeth Bauer 60 Think Like an Actuary to Assess and Mitigate 25 Hedging Against Inflation Risk With Real Annuities Retirement Risks Zvi Bodie and Dirk Cotton Ken Steiner 32 The 100-Month Protection Plan: A Private Social 66 Strategies for Addressing Retirement Risks Security Annuity Anil Suri and Nevenka Vrdoljak John Cutler 73 Layered Liquidity Management in Retirement Gwen Yun Weng This publication is provided for informational and educational purposes only. Neither the Society of Actuaries nor the respective authors’ employers make any endorsement, representation or guarantee with regard to any content, and disclaim any liability in connection with the use or misuse of any information provided herein. -

Annual Report for the Financial Year Ended 31 December 2020

United Global Diversified Portfolios United Income Focus Trust United Global Stable Select Equity Fund United Global Quality Growth Fund Annual Report for the financial year ended 31 December 2020 United Global Diversified Portfolios (Constituted under a Trust Deed in the Republic of Singapore) MANAGER UOB Asset Management Ltd Registered Address: 80 Raffles Place UOB Plaza Singapore 048624 Company Registration No. : 198600120Z Tel: 1800 22 22 228 DIRECTORS OF UOB ASSET MANAGEMENT LTD Lee Wai Fai Eric Tham Kah Jin PehKianHeng Thio Boon Kiat TRUSTEE State Street Trust (SG) Limited 168 Robinson Road #33-01, Capital Tower Singapore 068912 CUSTODIAN / ADMINISTRATOR / REGISTRAR State Street Bank and Trust Company, acting through its Singapore Branch 168 Robinson Road #33-01, Capital Tower Singapore 068912 AUDITOR PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP 7 Straits View, Marina One East Tower, Level 12 Singapore 018936 SUB-MANAGER (UNITED INCOME FOCUS TRUST AND UNITED GLOBAL QUALITY GROWTH FUND) Wellington Management Singapore Pte. Ltd. 8 Marina Boulevard #03-01, Tower 1, Marina Bay Financial Centre Singapore 018981 -1- United Income Focus Trust (Constituted under a Trust Deed in the Republic of Singapore) A) Fund Performance Class SGD Acc Since Inception 30 November 3yr 5yr 10 yr 2015 3mth 6mth 1yr Ann Ann Ann Ann Fund Performance/ % % % Comp Comp Comp Comp Benchmark Returns Growth Growth Growth Ret Ret Ret Ret United Income Focus Trust 2.49 1.23 -3.84 0.44 3.00 N/A 2.82 Benchmark 3.72 5.72 10.16 9.13 7.57 N/A 7.44 Source: Morningstar. Note: The performance returns of the Fund are in Singapore Dollar based on a NAV-to-NAV basis with dividends and distributions reinvested, if any. -

Annual Return

FORM NO. MGT-7 Annual Return [Pursuant to sub-Section(1) of section 92 of the Companies Act, 2013 and sub-rule (1) of (other than OPCs and Small rule 11of the Companies (Management and Companies) Administration) Rules, 2014] Form language English Hindi Refer the instruction kit for filing the form. I. REGISTRATION AND OTHER DETAILS (i) * Corporate Identification Number (CIN) of the company L85110KA1981PLC013115 Pre-fill Global Location Number (GLN) of the company * Permanent Account Number (PAN) of the company AAACI4798L (ii) (a) Name of the company INFOSYS LIMITED (b) Registered office address ELECTRONICS CITY,HOSUR ROAD, BANGALORE KARNATAKA Karnataka 560100 India (c) *e-mail ID of the company [email protected] (d) *Telephone number with STD code 08041167775 (e) Website www.infosys.com (iii) Date of Incorporation 02/07/1981 (iv) Type of the Company Category of the Company Sub-category of the Company Public Company Company limited by shares Indian Non-Government company (v) Whether company is having share capital Yes No (vi) *Whether shares listed on recognized Stock Exchange(s) Yes No Page 1 of 20 (a) Details of stock exchanges where shares are listed S. No. Stock Exchange Name Code 1 National Stock Exchange of India 1,024 2 BSE Limited 1 (b) CIN of the Registrar and Transfer Agent U72400TG2017PTC117649 Pre-fill Name of the Registrar and Transfer Agent KFIN TECHNOLOGIES PRIVATE LIMITED Registered office address of the Registrar and Transfer Agents Selenium, Tower B, Plot No- 31 & 32, Financial District, Nanakramguda, Serilingampally (vii) *Financial year From date 01/04/2020 (DD/MM/YYYY) To date 31/03/2021 (DD/MM/YYYY) (viii) *Whether Annual general meeting (AGM) held Yes No (a) If yes, date of AGM 19/06/2021 (b) Due date of AGM 30/09/2021 (c) Whether any extension for AGM granted Yes No II. -

2020 Proxy Statement

2020 Proxy Statement Notice of Capital One Financial Corporation’s 2020 Annual Stockholder Meeting Important Notice Regarding the Availability of Proxy Materials for The Stockholder Meeting To Be Held On April 30, 2020 The Proxy Statement and Annual Report to Stockholders are available at www.proxyvote.com The 2020 Annual Stockholder Meeting of Capital One Financial Corporation (“Capital One” or “Company”) will be a virtual meeting conducted exclusively via live webcast at www.virtualshareholdermeeting.com/COF2020 on April 30, 2020, at 10:00 a.m. Eastern Time. Items of Business As a stockholder, you will be asked to: ➊ Elect twelve nominated directors, who are listed in the proxy statement, as directors of Capital One; ➋ Ratify the selection of Ernst & Young LLP as our independent registered public accounting firm for 2020; ➌ Approve, on a non-binding advisory basis, our 2019 Named Executive Officer compensation (“Say on Pay”); ➍ Approve amendments to Capital One’s Restated Certificate of Incorporation to allow stockholders to act by written consent; and ➎ Consider a stockholder proposal regarding an independent Board chairman, if properly presented at the meeting. Stockholders also will transact other business that may properly come before the meeting. Record Date You may vote if you held shares of Capital One common stock as of the close of business on March 3, 2020 (“Record Date”). Proxy Voting Your vote is important. You may vote your shares in advance of the meeting via the Internet, by telephone or by mail, or by attending and voting online at the 2020 Annual Stockholder Meeting. Please refer to the section “How do I vote?” in the proxy statement for detailed voting instructions. -

Phillip Funds Focus

December 2019 34q234q Phillip Funds A MONTHLY NEWSLETTER EXCLUSIVELY FOR INVESTMENT PROFESSIONALS Focus A Brief Synopsis Where to Look Out For… Page The Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act of 2019, signed into law by …Window to the World 2 President Trump, is touted by Congress as a way to deter Beijing’s influence and interference in Hong Kong’s internal affairs. This may implies that the highly anticipated phase 1 trade negotiation will not go as smoothly as market …A Peep into Malaysia 2 expectations. In addition, on 3rd November, Donald Trump also announced that he is willing to wait for another year before striking a trade agreement with China. The signing of phase 1 trade agreement may roll into 2020 while the tariff scheduled on …Lighting Up Your Path 3 15th December may be implemented if things don’t go as planned. …Managed UT 4 Germany’s consumer sentiment rose unexpectedly where the improved mood among buyers is expected to give a boost to household spending and support the export-driven Germany economy, which has come under pressure from U.S.- …Tracking Our Recommendations 5 China trade tensions and Brexit uncertainty. Income expectations also improved in line with a strong labor market, rising wages, and moderate inflation, according to …From the Scoreboard 6-17 the institute, thanks to an unexpected drop in Germany unemployment, where the jobless rate held at 5% near a record low. On top of that, Germany narrowly avoided technical recession in 3Q19 with GDP growth of 0.1%. We expect Tokyo 2020 Olympics will be marked in history where AI-based applications will be deployed on a large scale, ranging from automated aggression detection, autonomous cars, pseudo 3D live broadcasting, humanoids and others. -

2018 RIC Attendees

Attendees’ Titles and Companies Job Title: Company Name: Client Care Accenture Pre-Sales Manager Accenture Sales and Client Management Lead Accenture Life & Annuity Software Senior Manager - Sales Accenture Life & Annuity Software SVP - Individual Annuity Products AIG VP Fixed Annuity Pricing AIG Financial Solutions Product Manager Alight Solutions, LLC Assistant Vice President Product Innovation Allianz Life Market Insights Manager Allianz Life Senior Product & Sales Consultant Allianz Life AVP - Product Development American Equity Investment Life Marketing Special Projects Director American Equity Investment Life Vice President American Equity Investment Life Vice President Regional & Field Marketing American Equity Investment Life VP Product Management American Equity Investment Life Market Intelligence Analyst American National Vice President Ameriprise Financial 2VP & Associate Actuary Ameritas Life Insurance Corp Retirement Plans Platform Specialist Ameritas Life Insurance Corp., Retirement Plans Partner Aon Annuity Specialist Auto-Owners Insurance Lead Director AXA Equitable Life Product & Life Risk AXA Equitable Life Senior Director & Actuary AXA Equitable Life Managing Director Bank of America Merrill Lynch Managing Director, Client Solutions Bank of America Merrill Lynch Insurance Solutions Barclays VP- Cross Asset Sales , US Barclays Account Executive - Pensions & Investments Bermuda Fire & Marine Co-Founder and CEO Blueprint Income Director - Insurance Sales BNP Paribas Managing Director BNP Paribas Managing Director BNP Paribas 1 VP, Equity Sales - Annuities Product Development BNP Paribas Director, Annuity Development Brighthouse Financial Senior Product Consultant Brighthouse Financial Partner Bryan Cave LLP Partner Bryan Cave LLP President CAB Consulting President & CEO Cannex Financial Exchanges Senior Quantitative Analyst CANNEX Financial Exchanges Ltd. Manager, Product Research CANNEX USA President, CANNEX USA Cannex USA Managing Director CAPTRUST Director of Business Strategy Charles Schwab & Co., Inc. -

United Income Plus Fund

United Income Plus Fund Annual Report 31 July 2020 UNITED INCOME PLUS FUND Audited Annual Report and Financial Statements For the Financial Year Ended 31 July 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE NO (A) MANAGER’S REPORT 2 (B) TRUSTEE’S REPORT 10 (C) STATEMENT BY MANAGER 11 (D) INDEPENDENT AUDITORS' REPORT TO THE UNIT HOLDERS 12 (E) FINANCIAL STATEMENTS STATEMENT OF FINANCIAL POSITION 16 STATEMENT OF COMPREHENSIVE INCOME 17 STATEMENT OF CHANGES IN NET ASSET VALUE 18 STATEMENT OF CASH FLOWS 19 NOTES TO THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 20 (F) CORPORATE INFORMATION 47 1 (A) MANAGER’S REPORT Dear Unitholders, We are pleased to present you the Manager’s report and the audited accounts of United Income Plus Fund (the “Fund”) for the financial year ended 31 July 2020. (1) Key Data of the Fund 1.1 Fund name United Income Plus Fund (the "Fund") 1.2 Fund category Fixed Income 1.3 Fund type Income & Growth 1.4 Investment The Fund seeks to provide investors with income and capital appreciation over objective the Medium to Long Term (i.e. a period of three (3) years or more) by investing primarily in fixed income securities with the remaining investing in equities and equity-related securities. 1.5 Performance With effective from 13 August 2015, the performance benchmark of the Fund benchmark has been changed as follows: • 70% 12 month fixed deposit rate by Malayan Banking Berhad; (available at www.maybank2u.com.my) • 30% FTSE Bursa Malaysia Kuala Lumpur Composite Index (FBM KLCI) (available at www.bursamalaysia.com) Prior to that, the performance benchmark of the Fund was: • 35% Quantshop All MGS Index; (available at www.quantshop.com) • 35% J.P. -

20190523 ADV Part 2 Update

Form ADV Part 2A – Appendix 1 BETTERMENT WRAP FEE BROCHURE Betterment 61 West 23rd Street 4th Floor New York, NY 10010 646-600-8263 www.betterment.com May 23, 2019 This wrap fee program brochure provides information about the qualifications and business practices of Betterment LLC (“Betterment”), a registered investment adviser. Registration does not imply a certain level of skill or training but only indicates that Betterment has registered its business with state and federal regulatory authorities, including the United States Securities and Exchange Commission. If you have any questions about the contents of this brochure, please contact us at [email protected]. The information in this brochure has not been approved or verified by the United States Securities and Exchange Commission or by any state securities authority. Additional information about Betterment is avAilable on the SEC’s website at www.adviserinfo.sec.gov. 1 Item 2: Summary of Material Changes The most recent annual update of this Wrap Fee Program brochure was March 29, 2019. On May 23, 2019, this brochure was further updated to reflect that Betterment Securities, Betterment’s broker-dealer affiliate, earns revenue for facilitating the processing and delivery of proxies. Updated: May 23, 2019. Copyright © Betterment LLC and Betterment Securities 2010 – 2019. All rights reserved. 2 Wrap Fee Brochure Table of Contents ITEM 2: SUMMARY OF MATERIAL CHANGES ............................................................................................... 2 WRAP FEE BROCHURE -

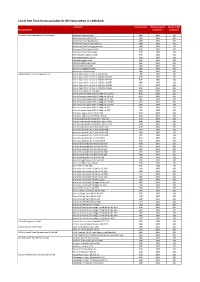

List of Unit Trust Funds Available for SRS Subscription in CIMB Bank

List of Unit Trust Funds available for SRS Subscription in CIMB Bank Fund Name Fund Currency Minimum Initial Minimum RSP Manager Name Investment Investment Aberdeen Asset Management Asia Limited Aberdeen American Opp SGD 1000 100 Aberdeen Asian Smaller Cos SGD 1000 100 Aberdeen China Opportunities SGD 1000 100 Aberdeen European Opportunities SGD 1000 100 Aberdeen Global Emerging Markets SGD 1000 100 Aberdeen Global Opportunities SGD 1000 100 Aberdeen Global Technology SGD 1000 100 Aberdeen India Opportunities SGD 1000 100 Aberdeen Indonesia Equity SGD 1000 100 Aberdeen Japan Equity SGD 1000 100 Aberdeen Malaysian Equity SGD 1000 100 Aberdeen Pacific Equity SGD 1000 100 Aberdeen Singapore Equity SGD 1000 100 Aberdeen Thailand Equity SGD 1000 100 Allianz Global Investors Singapore Ltd Allianz Asian Multi Inc Plus Cl AM Dis USD USD 1000 100 Allianz Asian Multi Inc Plus Cl AMg Dis H2-AUD AUD 1000 100 Allianz Asian Multi Inc Plus Cl AMg Dis H2-EUR EUR 1000 100 Allianz Asian Multi Inc Plus Cl AMg Dis H2-GBP GBP 1000 100 Allianz Asian Multi Inc Plus Cl AMg Dis H2-RMB CNH 1000 100 Allianz Asian Multi Inc Plus Cl AMg Dis H2-SGD SGD 1000 100 Allianz China Equity AT Acc SGD SGD 1000 100 Allianz Dynamic Asian HY Bd Cl AMg Dis H2-AUD AUD 1000 100 Allianz Dynamic Asian HY Bd Cl AMg Dis H2-EUR EUR 1000 100 Allianz Dynamic Asian HY Bd Cl AMg Dis H2-GBP GBP 1000 100 Allianz Dynamic Asian HY Bd Cl AMg Dis H2-RMB CNH 1000 100 Allianz Dynamic Asian HY Bd Cl AMg Dis H2-SGD SGD 1000 100 Allianz Dynamic Asian HY Bd Cl AMg Dis SGD SGD 1000 100 Allianz Dynamic