AHS 02 02 Content 20140102

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Silen Tvalle Y

S ilent Va lle y H otels & Resorts Our mission is to completely delight and satisfy our guests … www.silenvalley.com Hotels & Resorts Court Jn. Mannarkkad, Palakkad.Kerala. INDIA . Tel- 94447962613, 04924- 226819, 226 771 S ilent Va lle y Email: [email protected]. S ilent Valley We Belive in Quality S ilent Vallelley Welcome to Silent Valley Specialised Multi Cuisine Restaurant You should stay once at Hotel Silent Valley to experience this divine sensation. There are two State of the art amenities, star things you should never miss in life, the sea and the restaurant, shopping complex and silent valley. deluxe facilities. Located in the western ghats in the heart of Malabar, It is in this valley that the ultimate forest experience Hotel Silent Valley is strategically awaits you with all its grandeur. Pure air, crystal placed at Mannarkkad along Palakkad clear water, greenest visions, animals, you have only - Kozhikode National Highway heard of sounds you have never heard - We welcome Mannarkkad is the stepping stone to you to the nature's treasure trove. the perennial Rain forests of the Silent Valley National park. It is a piece of land, sandwiched between the Arabian sea and Western Ghats in Southern India is Hotel Silent Valley is centrally known as Kerala, which is also known as GOD’S situated so much so that Malampuzha OWN COUNTRY and Hotel Silent Valley is Gardens, Tippu's Fort, Siruvani situated in Mannarkkad of Pallakkadu District is Dam Meenvallam Water Falls, River one of the serene valleys of Western Ghats, which Wood Resorts, Kanjirapuzha Gardens precisely can be called as the LAP OF MOTHER etc are easily approachable from it. -

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with Financial Assistance from the World Bank

KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT (KSWMP) INTRODUCTION AND STRATEGIC ENVIROMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE Public Disclosure Authorized MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA VOLUME I JUNE 2020 Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by SUCHITWA MISSION Public Disclosure Authorized GOVERNMENT OF KERALA Contents 1 This is the STRATEGIC ENVIRONMENTAL ASSESSMENT OF WASTE MANAGEMENT SECTOR IN KERALA AND ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL MANAGEMENT FRAMEWORK for the KERALA SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT PROJECT (KSWMP) with financial assistance from the World Bank. This is hereby disclosed for comments/suggestions of the public/stakeholders. Send your comments/suggestions to SUCHITWA MISSION, Swaraj Bhavan, Base Floor (-1), Nanthancodu, Kowdiar, Thiruvananthapuram-695003, Kerala, India or email: [email protected] Contents 2 Table of Contents CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION TO THE PROJECT .................................................. 1 1.1 Program Description ................................................................................. 1 1.1.1 Proposed Project Components ..................................................................... 1 1.1.2 Environmental Characteristics of the Project Location............................... 2 1.2 Need for an Environmental Management Framework ........................... 3 1.3 Overview of the Environmental Assessment and Framework ............. 3 1.3.1 Purpose of the SEA and ESMF ...................................................................... 3 1.3.2 The ESMF process ........................................................................................ -

Malaria Control in South Malabar, Madras State

Bull. Org. mond. Sante | 1954, 11, 679-723 Bull. Wld Hlth Org. MALARIA CONTROL IN SOUTH MALABAR, MADRAS STATE L. MARA, M.D. Senior Adviser and Team-leader, WHO Malaria-Control Demonstration Team, Suleimaniya, Iraq formerly, Senior Adviser and Team-leader, WHO Malaria-Control Demonstration Team, South Malabar Manuscript received in January 1954 SYNOPSIS The author describes the activities and achievements of a two- year malaria-control demonstration-organized by WHO, UNICEF, the Indian Government, and the Government of Madras State- in South Malabar. Widespread insecticidal work, using a dosage of 200 mg of DDT per square foot (2.2 g per m2), protected 52,500 people in 1950, and 115,500 in 1951, at a cost of about Rs 0/13/0 (US$0.16) per capita. The final results showed a considerable decrease in the size of the endemic areas; in the spleen- and parasite-rates of children; and in the number of malaria cases detected by the team or treated in local hospitals and dispensaries. During December 1949 a malaria-control project, undertaken jointly by WHO, the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), the Govern- ment of India, and the Government of Madras State, started operations in the malarious areas among the foothills and tracts of Ernad and Walavanad taluks in South Malabar. During 1951 the operational area was extended to include almost all the malarious parts of Ernad and Walavanad as well as the northernmost part of Palghat taluk (see map 1 a). The staff of the international team provided by WHO consisted of a senior adviser and team-leader and a public-health nurse. -

Building a Reliable Storage Stack

Building a Reliable Storage Stack Ph.D. Thesis David Cornelis van Moolenbroek Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, 2016 This work was supported by the European Research Council Advanced Grant 227874. This work was carried out in the ASCI graduate school. ASCI dissertation series number 355. Copyright © 2016 by David Cornelis van Moolenbroek. ISBN 978-94-028-0240-5 Cover design by Eva Dienske. Printed by Ipskamp Printing. VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT Building a Reliable Storage Stack ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. V. Subramaniam, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van de promotiecommissie van de Faculteit der Exacte Wetenschappen op maandag 12 september 2016 om 11.45 uur in de aula van de universiteit, De Boelelaan 1105 door David Cornelis van Moolenbroek geboren te Amsterdam promotor: prof.dr. A.S. Tanenbaum To my parents Acknowledgments This book marks the end of both a professional and a personal journey–one that has been long but rewarding. There are several people whom I would like to thank for accompanying and helping me along the way. First and foremost, I would like to thank my promotor, Andy Tanenbaum. While I was finishing up my master project under his supervision, he casually asked me “Would you like to be my Ph.D student?” during one of our meetings. I did not have to think long about the answer. Right from the start, he warned me that I would now have to conduct original research myself; only much later did I understand the full weight of this statement. -

Free Software Philosophy, History and Practice

Introduction (and some quick reminders) History and philosophy Legal aspects Free Software Philosophy, history and practice Luca Saiu [email protected] http://ageinghacker.net GNU Project Screencast version Paris, October 2014 Luca Saiu <[email protected]> Free Software — Philosophy, history and practice Introduction (and some quick reminders) History and philosophy Legal aspects Introducing myself I’m a computer scientist living and working somewhere around Paris... ...and a GNU maintainer. I’m also an associate member of the Free Software Foundation, a fellow of the Free Software Foundation Europe and an April adherent. So I’m not an impartial observer. Luca Saiu <[email protected]> Free Software — Philosophy, history and practice Introduction (and some quick reminders) History and philosophy Legal aspects Contents 1 Introduction (and some quick reminders) 2 History and philosophy The hacker community The GNU Project and the Free Software movement Linux and the Open Source movement 3 Legal aspects Copyright Free Software licenses Luca Saiu <[email protected]> Free Software — Philosophy, history and practice Introduction (and some quick reminders) History and philosophy Legal aspects Reminders about software — source code vs. machine code Source code vs. machine code Quick demo Luca Saiu <[email protected]> Free Software — Philosophy, history and practice Programs are linked to libraries static libraries shared libraries Libraries (or programs) request services to the kernel Programs invoke with other programs Programs communicate with other programs... ...on the same machine ...over the network We’re gonna see that this has legal implications. Introduction (and some quick reminders) History and philosophy Legal aspects Reminders about software — linking In practice, programs don’t exist in isolation. -

Native Goat Breeds of Kerala

taluk and on the west by Mannarghat taluk of Pudur, Agali and Sholayur panchayaths, of the Palaghat District and Eranad taluk of which have scanty vegetation. They are the Malappuram district. tailored to grazing habit. When food is limited, these animals are good at adapting This region is inhabited by some of the to the available fodder. major tribal communities of thew State known as Irules, Mudukas and Kurumbas. Facing Extinction The tribal economy is dependent mainly on goat rearing and agricultural activities. They The uncontrolled natural breeding of female treat goats as their family members and goats by non-descript bucks which occur call kids a ectionately as “vava” (Baby). The during grazing time has led to the dilution goat has cultural values too. The wealth of of the breed at a faster rate. Attappady a tribal family is measured by the number Black goats represents only 40% of the total of goats reared in the house. Many times, goat population in the area now. According they are gifted to newly married couples. to a recent survey by Kerala Agricultural Tribal communities believe that milk and University the estimated total population Native Goat meat of the goat act as a certain extent, the of Attappady black goats in their breeding milk and meat of the goat as a safeguard tract is as low as 5,595, putting this breed Breeds of against malnutrition in thses remote areas. of goats under the insecure category listed by the FAO. Kerala The local goat variety envolved and developed solely by the these tribes over the During the year 1989 a Government Goat ages are medium sized, lean, slender bodied Farm was established at Attappadi with a Attappadi Black Goat and black in the color. -

A Checklist of Birds of Kerala, India

Journal of Threatened Taxa | www.threatenedtaxa.org | 17 November 2015 | 7(13): 7983–8009 A checklist of birds of Kerala, India Praveen J ISSN 0974-7907 (Online) B303, Shriram Spurthi, ITPL Main Road, Brookefields, Bengaluru, Karnataka 560037, India ISSN 0974-7893 (Print) Communication Short [email protected] OPEN ACCESS Abstract: A checklist of birds of Kerala State is presented in this pa- significant inventory of birds of Kerala was by Ferguson per. Accepted English names, scientific binomen, prevalent vernacular & Bourdillon (1903–04) who provided an annotated names in Malayalam, IUCN conservation status, endemism, Wildlife (Protection) Act schedules, and the appendices in the CITES, pertain- checklist of 332 birds from the princely state of ing to the birds of Kerala are also given. The State of Kerala has 500 Travancore. However, the landmark survey of the states species of birds, 17 of which are endemic to Western Ghats, and 24 species fall under the various threatened categories of IUCN. of Travancore and Cochin by Dr. Salim Ali in 1933–34 is widely accepted as the formal foundation in ornithology Keywords: CITES, endemism, Malayalam name, vernacular name, of Kerala. These surveys resulted in two highly popular Western Ghats, Wildlife (Protection) Act. books, The Birds of Travancore and Cochin (Ali 1953) and Birds of Kerala (Ali 1969); the latter listed 386 species. After two decades, Neelakantan et al. (1993) compiled Birds are one of the better studied groups of information on 95 bird species that were subsequently vertebrates in Kerala. The second half of 19th century recorded since Ali’s work. Birds of Kerala - Status and was dotted with pioneering contributions from T.C. -

The Flask Security Architecture: System Support for Diverse Security Policies

The Flask Security Architecture: System Support for Diverse Security Policies Ray Spencer Secure Computing Corporation Stephen Smalley, Peter Loscocco National Security Agency Mike Hibler, David Andersen, Jay Lepreau University of Utah http://www.cs.utah.edu/flux/flask/ Abstract and even many types of policies [1, 43, 48]. To be gen- erally acceptable, any computer security solution must Operating systems must be flexible in their support be flexible enough to support this wide range of security for security policies, providing sufficient mechanisms for policies. Even in the distributed environments of today, supporting the wide variety of real-world security poli- this policy flexibility must be supported by the security cies. Such flexibility requires controlling the propaga- mechanisms of the operating system [32]. tion of access rights, enforcing fine-grained access rights and supporting the revocation of previously granted ac- Supporting policy flexibility in the operating system is cess rights. Previous systems are lacking in at least one a hard problem that goes beyond just supporting multi- of these areas. In this paper we present an operating ple policies. The system must be capable of supporting system security architecture that solves these problems. fine-grained access controls on low-level objects used to Control over propagation is provided by ensuring that perform higher-level functions controlled by the secu- the security policy is consulted for every security deci- rity policy. Additionally, the system must ensure that sion. This control is achieved without significant perfor- the propagation of access rights is in accordance with mance degradation through the use of a security decision the security policy. -

Southern India Project Elephant Evaluation Report

SOUTHERN INDIA PROJECT ELEPHANT EVALUATION REPORT Mr. Arin Ghosh and Dr. N. Baskaran Technical Inputs: Dr. R. Sukumar Asian Nature Conservation Foundation INNOVATION CENTRE, INDIAN INSTITUTE OF SCIENCE, BANGALORE 560012, INDIA 27 AUGUST 2007 CONTENTS Page No. CHAPTER I - PROJECT ELEPHANT GENERAL - SOUTHERN INDIA -------------------------------------01 CHAPTER II - PROJECT ELEPHANT KARNATAKA -------------------------------------------------------06 CHAPTER III - PROJECT ELEPHANT KERALA -------------------------------------------------------15 CHAPTER IV - PROJECT ELEPHANT TAMIL NADU -------------------------------------------------------24 CHAPTER V - OVERALL CONCLUSIONS & OBSERVATIONS -------------------------------------------------------32 CHAPTER - I PROJECT ELEPHANT GENERAL - SOUTHERN INDIA A. Objectives of the scheme: Project Elephant was launched in February 1992 with the following major objectives: 1. To ensure long-term survival of the identified large elephant populations; the first phase target, to protect habitats and existing ranges. 2. Link up fragmented portions of the habitat by establishing corridors or protecting existing corridors under threat. 3. Improve habitat quality through ecosystem restoration and range protection and 4. Attend to socio-economic problems of the fringe populations including animal-human conflicts. Eleven viable elephant habitats (now designated Project Elephant Ranges) were identified across the country. The estimated wild population of elephants is 30,000+ in the country, of which a significant -

![Temple Entry Movement for Depressed Class in South Travancore [Kanyakumari] Prathika](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3132/temple-entry-movement-for-depressed-class-in-south-travancore-kanyakumari-prathika-703132.webp)

Temple Entry Movement for Depressed Class in South Travancore [Kanyakumari] Prathika

Prathika. S al. International Journal of Institutional & Industrial Research ISSN: 2456-1274, Vol. 3, Issue 1, Jan-April 2018, pp.4-7 Temple Entry Movement for Depressed Class in South Travancore [Kanyakumari] Prathika. S Ph.D. Research Scholar, Department of History and Research Centre, S.T. Hindu College, Nagercoil 629002. Abstract: The four Tamil speaking taluks of Kanyakumari Dist viz;Agasteeswaram, Thovalai, Kalkulam and Vilavancode consisted the erst while South Tavancore. Among the various religions, Hinduism is the predominant one constituting about two third of the total population. The important Hindu temples found in Kanyakumari District are at Kanyakumari, Suchindrum, Kumarakoil,Nagercoil, Thiruvattar and Padmanabhapuram. The village God like Madan,Isakki, Sasta are worshipped by the Hindus. The people of South Travancore segregated and lived on the basis of caste. The whole population could be classified as Avarnas or Caste Hindus and Savarnas or non-caste people. The Savarnas such as Brahmins, Kshatriyas, Vaishyas, and Sudras who enjoyed special powers and privileges of wealth constituted the higher castes. The Avarnas viz the Nadars, Ezhavas, Mukkuvas, Sambavars, Pulayas and numerous hill tribes were considered as the polluting castes and were looked down on and had to perform various services for the Savarnas . Avarnas were not allowed in public places, temples, and the temple roads also. Low caste people or Avarnas were considered as untouchable people. Untouchability, one of the major debilities prevailed among the lower order of the society in South Travancore caused an indelible impact on the society. Keywords: Temple Entry Movement, Depressed Class, Kanyakumari reformers against that oppressive activities. -

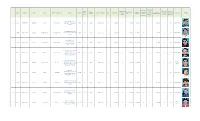

ADIP Beneficiary Data 2017-18

Boarding Travel cost Age / Fabrication/ and No. of days whether Monthly Total Cost of Subsidy paid to out Totel of State District Date Name Father's / Husband's Address Gender Birth Type of Aid Given Qty. Cost of Aid Fitment Loadging for which accompanie Category PHOTO Income Aid Provided station (12+13+14+15) Year Charge Expences stayed d by escort beneficiary paid Puthenpeedika, Tana, 1 Kerala Malappuram 10-01-18 Nuhman Muhammed Pullippadam, Malappuram- Male 16 2,666 TLM 12 - 18 1 6,140.00 0 6140.00 6,140.00 0 0 6,140.00 0 YES Muslim (OBC) 676542 Nediyapparambil House, 2 Kerala Malappuram 10-01-18 Akshay Dev V K Damodaran N P Nilambur Post, Malappuram- Male 17 3,500 TLM 12 - 18 1 6,140.00 0 6140.00 6,140.00 0 0 6,140.00 0 YES Muslim (OBC) 679329 Veluthedath House, Vadakkumpadam Post, 3 Kerala Malappuram 10-01-18 Akshaya K R Radhakrishnan Female 16 4000 TLM 12 - 18 1 6,140.00 0 6140.00 6,140.00 0 0 6,140.00 0 YES Muslim (OBC) Vandoor, Nilambur, Malappuram Panthalingal, Kaattumunda, Pallippad, Naduvath, 4 Kerala Malappuram 10-01-18 Aslah P Mustafa P Male 12 2,500 TLM 12 - 18 1 6,140.00 0 6140.00 6,140.00 0 0 6,140.00 0 YES Muslim (OBC) Mambad Village, Thiruvali, Malappuram-679328 Cheenkanniparackal, Kattmunda, Naduvath Post, Christian 5 Kerala Malappuram 10-01-18 Sneha Philipose Philipose Female 17 4000 TLM 12 - 18 1 6,140.00 0 6140.00 6,140.00 0 0 6,140.00 0 YES Vandoor Village, Thiruvali, General Malappuram-679328 Palakkodan, Chenakkulangara, Naduvath 6 Kerala Malappuram 10-01-18 Linju P Narayanan Female 14 1500 TLM 12 - 18 1 6,140.00 -

Assessment of Biodiversity Loss Along the Flood and Landslide-Hit Areas of Attappady Region, Palakkad District, Using Geoinformatics

ASSESSMENT OF BIODIVERSITY LOSS ALONG THE FLOOD AND LANDSLIDE-HIT AREAS OF ATTAPPADY REGION, PALAKKAD DISTRICT, USING GEOINFORMATICS Report submitted To Kerala State Biodiversity Board, Thiruvananthapuram. Submitted By Government College Chittur, Palakkad. Project summary Assessment of biodiversity loss along the flood and 1 Title landslide-hit areas of Attappady region, Palakkad district using geoinformatics. Kerala State Biodiversity Board 2 Project funded by L-14, Jai Nagar Medical College P.O. Thiruvananthapuram-695 011 3 Project period January 2019 – March 2019 Dr. Richard Scaria (Principal Investigator) Sojan Jose (Co-Investigator) Aswathy R. (Project Fellow - Zoology) Smitha P.V. (Project Fellow - Botany) Vincy V. (Project Fellow - Geography) 4 Project team Athulya C. (Technical Assistant - Zoology) Jency Joy (Technical Assistant - Botany) Ranjitha R. (Technical Assistant - Botany) Krishnakumari K. (Technical Assistant - Botany) Hrudya Krishnan K. (Technical Assistant - Botany) Identification of the geographical causes of flood and landslides in Attappady. Construction of maps of flood and landslide-hit areas and susceptible zones. Proposal of effective land use plans for the mitigation of flood and landslides. 5 Major outcomes Estimation of damages due to landslides and flood. Assessment of the biodiversity loss caused by flood and landslides. Diversity study of major floral and faunal categories. Post flood analysis of soil fertility variation in riparian zones. Prof. Anand Viswanath. R Dr. Richard Scaria Sojan Jose Principal, (Principal Investigator) (Co-Investigator) Govt. College, Chittur, Department of Geography, Department of Botany, Palakkad. Govt. College, Chittur, Govt. College, Chittur, Palakkad. Palakkad. 1. Introduction Biodiversity is the immense variety and richness of life on Earth which includes different animals, plants, microorganisms etc.