African Perspectives on Global Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I the Use of African Music in Jazz from 1926-1964: an Investigation of the Life

The Use of African Music in Jazz From 1926-1964: An Investigation of the Life, Influences, and Music of Randy Weston by Jason John Squinobal Batchelor of Music, Berklee College of Music, 2003 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Ethnomusicology University of Pittsburgh 2007 i UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This thesis was presented by Jason John Squinobal It was defended on April 17, 2007 and approved by Dr. Nathan T. Davis, Professor, Music Department Dr. Akin Euba, Professor, Music Department Dr. Eric Moe, Professor, Music Department Thesis Director: Dr. Nathan T. Davis, Professor, Music Department ii Copyright © by Jason John Squinobal 2007 iii The Use of African Music in Jazz From 1926-1964: An Investigation of the Life, Influences, and Music of Randy Weston Jason John Squinobal, M.A. University of Pittsburgh, 2007 ABSTRACT There have been many jazz musicians who have utilized traditional African music in their music. Randy Weston was not the first musician to do so, however he was chosen for this thesis because his experiences, influences, and music clearly demonstrate the importance traditional African culture has played in his life. Randy Weston was born during the Harlem Renaissance. His parents, who lived in Brooklyn at that time, were influenced by the political views that predominated African American culture. Weston’s father, in particular, felt a strong connection to his African heritage and instilled the concept of pan-Africanism and the writings of Marcus Garvey firmly into Randy Weston’s consciousness. -

Fact Sheet: African Union Response to the Ebola Epidemic in West Africa, As of 1/26/2015

AFRICAN UNION: Support to EBOLA outbreak in West Africa ASEOWA FACT SHEET: AFRICAN UNION RESPONSE TO THE EBOLA EPIDEMIC IN WEST AFRICA, AS OF 1/26/2015 The Ebola outbreak was first reported in December 2013 in Guinea. meetings are held under the guidance of the Director of Social Affairs, As the African Union has stressed, the current outbreak of the Ebola Dr Olawale Maiyegun. Virus Disease is the worst that has ever been experienced since the first outbreak in 1976. Through its Peace and Security Council and the Dr. Julius Oketta, who has previous experience in dealing with Ebola,was Executive Committee and the various mechanisms put in place, the AU appointed ASEOWA Head of Mission. Mrs Wynne Musabayana is the is working alongside other major actors to bring an end to the spread of ASEOWA communications lead. the disease. CONCEPT OF OPERATIONS DONE MEETING OF MINISTERS OF HEALTH The ASEOWA Concept of Operations (CONOPs) envisages having up The AU response to Ebola started in April 2014 at the first 1st African to 1000 health workers in the field, on a rotational basis over a six month Ministers of Health Meeting jointly convened by the African Union period (December 2014-May 2015), to be assessed based on whether Commission (AUC) and the World Health Organisation (WHO) in Luanda, the affected countries are declared Ebola free. The ASEOWA deployment Angola. A strong Communiqué and an appeal to Member States with cycle is divided into three stages: Pre-deployment, Deployment and Exit experience in handling Ebola disease to assist were issued. -

Africa South Africa, Kenya, Tanzania, Namibia, Zimbabwe, Egypt & Morocco

AFRICA SOUTH AFRICA, KENYA, TANZANIA, NAMIBIA, ZIMBABWE, EGYPT & MOROCCO YOUR 2020 VACATION Africa_Cover_2020_CA.indd 1 11/04/2019 09:39 OUR AFRICA. 73 YEARS IN THE MAKING WELCOME ON A JOURNEY TO DISCOVER THE REAL AFRICA IN A WAY THAT ONLY WE CAN SHOW YOU. WELCOME TO OUR AFRICA, THE PLACE WE CALL HOME. Behind the Trafalgar brand is a passionate African family who Through our family roots, connections and stories born on delights in bringing their homeland to life through awe-inspiring this very continent, we show you the Africa many others will trips that give you a deeper understanding of this dynamic land. never see. Experience the Africa of your dreams come to life as the sun sets over golden-hued plains, as you savor a second Founded by Stanley Tollman, The Travel Corporation (TTC) is an helping of a home-cooked meal, as your feet tap along to the award-winning portfolio of brands, including Trafalgar, that hypnotic rhythms of African drums, feeling the spirit of Africa is 100% African-owned and operated, and driven by passion, that has lived on in our family for generations. We share the family values and providing exceptional service to more than magic so you can feel the same passion we feel; to gain an two-million guests each year. understanding of how it fuels the soul in unimaginable ways. To discover more about our other brands, see page 35. The Best of Africa SHARING OUR HOMELAND Meet the Tollman family, Trafalgar’s owners, pictured here in the wilds of Southern Africa. -

Bballdipaf2020 Syra Sylla

“Basketball Diplomacy in Africa: An Oral History from SEED Project to the Basketball Africa League (BAL)” An Information & Knowledge Exchange project funded by SOAS University of London. Under the direction of Dr J Simon Rofe, Reader in Diplomatic and International Studies, Centre for International Studies and Diplomacy, SOAS University of London [email protected] Transcript: Syra Sylla Basketball Storyteller Founder, The Lady Hoop Founder, Women’s Sport Story Conducted by Dr Lindsay Sarah Krasnoff Research Associate, Centre for International Studies and Diplomacy, SOAS University of London [email protected] Dr Lindsay Sarah Krasnoff For the record, could you start by just giving us your name, your age and how your first arrived to the basketball world? Syra Sylla My name is Syra Sylla. My parents are from Senegal, and I’m 36 years old. I first arrived in the basketball world when I was 18. One of my friends brought me to a basketball game, and that’s how I fell in love with basketball. The day after, I got on the basketball team, and since this day, I’ve played basketball, and am working in basketball. Dr Lindsay Sarah Krasnoff Right, doing all kinds of work in and around the basketball world. And so you grew up mostly in France. Could you just explain a little bit to our listeners, how did you first become involved with basketball in Africa? And you’ve done a lot of work there, especially in Senegal, what has driven your work on the continent thus far? Syra Sylla So, as you said, I grew up in France, but as a kid I went to Senegal in the summer every two years with my parents, so it was only for holidays that I was with my family [there]. -

African Musicology On-Line

AFRICAN MUSICOLOGY ON-LINE (An international, peer-reviewed, e-journal on African Musicology) (Vol. 2, No. 2) ISSN: 1994-7712 ___________________________________________________________ Bureau for the Development of African Musicology (BDAM) C/o H.O. Odwar, Department of Creative & Performing Arts, Maseno University, Kenya. ‘African Musicology Online’ 2(2), 2008 ii ________________________________________________________________________ 'AFRICAN MUSICOLOGY ON-LINE' Vol.2, No.2 [2008] (An international, peer-reviewed e-journal on African Musicology) is published by: Bureau for the Development of African Musicology (BDAM) C/o H.O. Odwar, Department of Creative & Performing Arts, Maseno University, Kenya. © 2008. All Rights Reserved. BDAM. ISSN: 1994-7712 The aims and objective of 'African Musicology Online' are as follows: - To serve as the voice of Africans at the international level in the study of their own Music; - To publish original research papers and reviews by Africans on their own music (encompassing all categories of African music); - To foster mutual co-operation among African scholars in the field of African Musicology; - To promote and develop the concept and practice of African Musicology, by Africans. All enquiries and correspondences should be directed to: The Editor <[email protected]> ‘African Musicology Online’ 2(2), 2008 iii EDITORIAL Editor in Chief Dr. Hellen Otieno Odwar Editorial Board Prof. Akosua O. Addo (U.S.A) Dr. Hellen O. Odwar (Kenya) Dr. ‘Femi Adedeji (Nigeria) Dr. Richard Amuah (Ghana) Edward L. Morakeng (South-Africa) Dr. John Baboukis (Egypt) Prof. Minette Mans (Namibia) Other Editors (Review) Dr. William O. Anku (Ghana) Dr. Zabana Kongo (Ghana) Prof. C. E. Nbanugo (Nigeria) Dr. A. A. Ogisi (Nigeria) Dr. -

Au Echo 2021 1 Note from the Editor

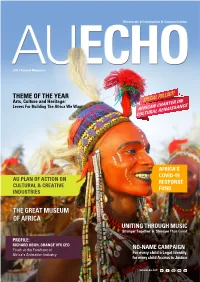

Directorate of Information & Communication 2021 Annual Magazine THEME OF THE YEAR Arts, Culture and Heritage: Levers For Building The Africa We Want AFRICAN CHARTER ON CULTURAL RENAISSANCE AFRICA’S COVID-19 AU PLAN OF ACTION ON RESPONSE CULTURAL & CREATIVE FUND INDUSTRIES THE GREAT MUSEUM OF AFRICA UNITING THROUGH MUSIC ‘Stronger Together’ & ‘Stronger Than Covid’ PROFILE: RICHARD OBOH, ORANGE VFX CEO Youth at the Forefront of NO-NAME CAMPAIGN Africa’s Animation Industry For every child a Legal Identity, for every child Access to Justice www.au.int AU ECHO 2021 1 NOTE FROM THE EDITOR he culture and creative industries (CCIs) generate annual global revenues of up to US$2,250 billion dollars and Texports in excess of US$250 billion. This sector currently provides nearly 30 million jobs worldwide and employs more people aged 15 to 29 than any other sector and contributes LESLIE RICHER up to 10% of GDP in some countries. DIRECTOR Directorate of Information & In Africa, CCIs are driving the new economy as young Africans Communication tap into their unlimited natural resource and their creativity, to create employment and generate revenue in sectors traditionally perceived as “not stable” employment options. taking charge of their destiny and supporting the initiatives to From film, theatre, music, gaming, fashion, literature and art, find African solutions for African issues. On Africa Day (25th the creative economy is gradually gaining importance as a May), the African Union in partnership with Trace TV and All sector that must be taken seriously and which at a policy level, Africa Music Awards (AFRIMA) organised a Virtual Solidarity decisions must be made to invest in, nurture, protect and grow Concert under the theme ‘Stronger Together’ and ‘Stronger the sectors. -

Theme of the Year the Great Museum of Africa the Great Museum of Africa

Directorate of Information & Communication 2021 Annual Magazine THEME OF THE YEAR Arts, Culture and Heritage: Levers For Building The Africa We Want AFRICAN CHARTER ON CULTURAL RENAISSANCE AFRICA’S COVID-19 AU PLAN OF ACTION ON RESPONSE CULTURAL & CREATIVE FUND INDUSTRIES THE GREAT MUSEUM OF AFRICA UNITING THROUGH MUSIC ‘Stronger Together’ & ‘Stronger Than Covid’ PROFILE: RICHARD OBOH, ORANGE VFX CEO Youth at the Forefront of NO-NAME CAMPAIGN Africa’s Animation Industry For every child a Legal Identity, for every child Access to Justice www.au.int AU ECHO 2021 1 NOTE FROM THE EDITOR he culture and creative industries (CCIs) generate annual global revenues of up to US$2,250 billion dollars and Texports in excess of US$250 billion. This sector currently provides nearly 30 million jobs worldwide and employs more people aged 15 to 29 than any other sector and contributes LESLIE RICHER up to 10% of GDP in some countries. DIRECTOR Directorate of Information & In Africa, CCIs are driving the new economy as young Africans Communication tap into their unlimited natural resource and their creativity, to create employment and generate revenue in sectors traditionally perceived as “not stable” employment options. taking charge of their destiny and supporting the initiatives to From film, theatre, music, gaming, fashion, literature and art, find African solutions for African issues. On Africa Day (25th the creative economy is gradually gaining importance as a May), the African Union in partnership with Trace TV and All sector that must be taken seriously and which at a policy level, Africa Music Awards (AFRIMA) organised a Virtual Solidarity decisions must be made to invest in, nurture, protect and grow Concert under the theme ‘Stronger Together’ and ‘Stronger the sectors. -

Growth and Development in Africa

HIS YEAR has seen a unique convergence Tof events for the ‘Africa Agenda’ and it may very well be the year that determines the continent’s future. In March, the UK’s Commission for Africa published its recommendations, providing a much- needed platform for the global community to reassess its views on Africa. Tony Blair is “African governments must unleash the strong committed to placing Africa at the top of his entrepreneurial spirit of Africa’s people. To promote agenda during the UK’s presidency of the G8 and the EU, and with the Commission for Africa’s this, donor governments and the private sector report he now has the material with which to work. should co-ordinate the efforts behind the proposed A new generation of increasingly democratically Investment Climate Facility (ICF) of the African elected African leaders are recognising that they must commit to good governance, investment and Union’s NEPAD programme…” Our Common Interest: growth. Notwithstanding deeply-rooted poverty and Commission for Africa Report conflict in many areas, a sea change in economic and political governance has begun in many African countries, with a number of real improvements in macro-economic stability and growth. The World Bank’s World Development Report 2005, A better investment climate for everyone Growth and helped to raise and renew awareness of the fundamentals for sustainable growth and poverty reduction. Investment climate reforms help explain China’s achievement in lifting 400 million people development out of poverty, India’s success in doubling its growth and Uganda’s ability to grow eight times the average of other sub-Saharan countries over the last decade. -

West African Music in the Music of Art Blakey, Yusef Lateef, and Randy Weston

West African Music in the Music of Art Blakey, Yusef Lateef, and Randy Weston by Jason John Squinobal Batchelor of Music, Music Education, Berklee College of Music, 2003 Master of Arts, Ethnomusicology, University of Pittsburgh, 2007 Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Ethnomusicology University of Pittsburgh 2009 ffh UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES This dissertation was presented by Jason John Squinobal It was defended on April 14, 2009 and approved by Dr. Nathan T. Davis, Professor, Music Department Dr. Akin Euba, Professor, Music Department Dr. Eric Moe, Professor, Music Department Dr. Joseph K. Adjaye, Professor, Africana Studies Dissertation Director: Dr. Nathan T. Davis, Professor, Music Department ii Copyright © by Jason John Squinobal 2009 iii West African Music in the Music of Art Blakey, Yusef Lateef, and Randy Weston Jason John Squinobal, PhD University of Pittsburgh, 2009 Abstract This Dissertation is a historical study of the cultural, social and musical influences that have led to the use of West African music in the compositions and performance of Art Blakey, Yusef Lateef, and Randy Weston. Many jazz musicians have utilized West African music in their musical compositions. Blakey, Lateef and Weston were not the first musicians to do so, however they were chosen for this dissertation because their experiences, influences, and music clearly illustrate the importance that West African culture has played in the lives of African American jazz musicians. Born during the Harlem Renaissance each of these musicians was influenced by the political views and concepts that predominated African American culture at that time. -

Black Power in South Africa: the Evolution of an Ideology

Black power in South Africa: the evolution of an ideology http://www.aluka.org/action/showMetadata?doi=10.5555/AL.SFF.DOCUMENT.crp2b20026 Use of the Aluka digital library is subject to Aluka’s Terms and Conditions, available at http://www.aluka.org/page/about/termsConditions.jsp. By using Aluka, you agree that you have read and will abide by the Terms and Conditions. Among other things, the Terms and Conditions provide that the content in the Aluka digital library is only for personal, non-commercial use by authorized users of Aluka in connection with research, scholarship, and education. The content in the Aluka digital library is subject to copyright, with the exception of certain governmental works and very old materials that may be in the public domain under applicable law. Permission must be sought from Aluka and/or the applicable copyright holder in connection with any duplication or distribution of these materials where required by applicable law. Aluka is a not-for-profit initiative dedicated to creating and preserving a digital archive of materials about and from the developing world. For more information about Aluka, please see http://www.aluka.org Black power in South Africa: the evolution of an ideology Author/Creator Gerhart, Gail M. Publisher University of California Press (Berkeley) Date 1978 Resource type Books Language English Subject Coverage (spatial) South Africa Coverage (temporal) 1943 - 1978 Source Northwestern University Libraries, Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies, 968 G368bl Rights By kind permission of Gail M. Gerhart. Description This book traces the evolution of Africanist and Black Consciousness thinking, from the ANC Youth League and the Pan Afrianist Congress through the Black Consciousness Movement of the 1970s. -

Police, Native and Location in Nairobi, 1844-1906

The Bleaching Carceral: Police, Native and Location in Nairobi, 1844-1906 Yannick Marshall Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2017 © 2017 Yannick Marshall All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Bleaching Carceral: Police, Native and Location in Nairobi, 1844-1906 Yannick Marshall This dissertation provides a history of the white supremacist police-state in Nairobi beginning with the excursions of European-led caravans and ending with the institutionalizing of the municipal entity known as the township of Nairobi. It argues that the town was not an entity in which white supremacist and colonial violence occurred but that it was itself an effect white supremacy. It presents the invasion of whiteness into the Nairobi region as an invasion of a new type of power: white supremacist police power. Police power is reflected in the flogging of indigenous peoples by explorers, settlers and administrators and the emergence of new institutions including the constabulary, the caravan, the “native location” and the punitive expedition. It traces the transformation of the figure of the indigenous other as “hostile native,” “raw native,” “native,” “criminal-African” and finally “African.” The presence of whiteness, the things of whiteness, and bodies racialized as white in this settler-colonial society were corrosive and destructive elements to indigenous life and were foundational to the construction of the first open-air prison in the East -

Religion and Politics in Kenya

Henry Martyn Lectures 2005 Religion and Politics in Kenya Professor John Lonsdale A series of three lectures was given by Professor John Lonsdale of Trinity College, Cambridge on Monday 7th, Tuesday 8th and Wednesday 9th February at the Faculty of Divinity, West Road, Cambridge. The lecture titles were: Foundations , Conflicts and Questions. Guests who attended the reception, which followed the first lecture included: The High Commissioner of Kenya, His Excellency, Mr Joseph Muchemi/Bishop Simon Barrington-Ward/Dr Brian Stanley Mrs Muchemi and Mrs Moya Lonsdale THE HENRY MARTYN LECTURES 2005 "Religion and Politics in Kenya" by John Lonsdale Trinity College, Cambridge LECTURE 1: Monday 7th February 2005 FOUNDATIONS Introduction Two centuries ago, in 1805, the young Henry Martyn left his fellowship at St John's College and curacy at Holy Trinity Church to set sail for India. In his first five years out there, as chaplain to the East India Company, he had translated the New Testament into Urdu and Persian. In his short life he also helped in the translation of the Gospels into Arabic. Much of what I have to say in these three lectures given in his honour is an historian's comment on the consequences of vernacular translations of the Bible, especially their gifts to political identity in Kenya and to that country's sometimes critical, sometimes vainglorious, language of politics. Some of these gifts of the translated Word can be counted as blessings to the people of Kenya, some as hindrances. The ambiguity of the relations between religion and politics in the modern history of that country lies at the core of what I have to say.