0666d73c299e1a1df1b16f7db322595f.doc Page 1 of 57

REMEMBER TO SAVE THE BLANK WORKSHEET TEMPLATE USING THE FILENAME FORMAT

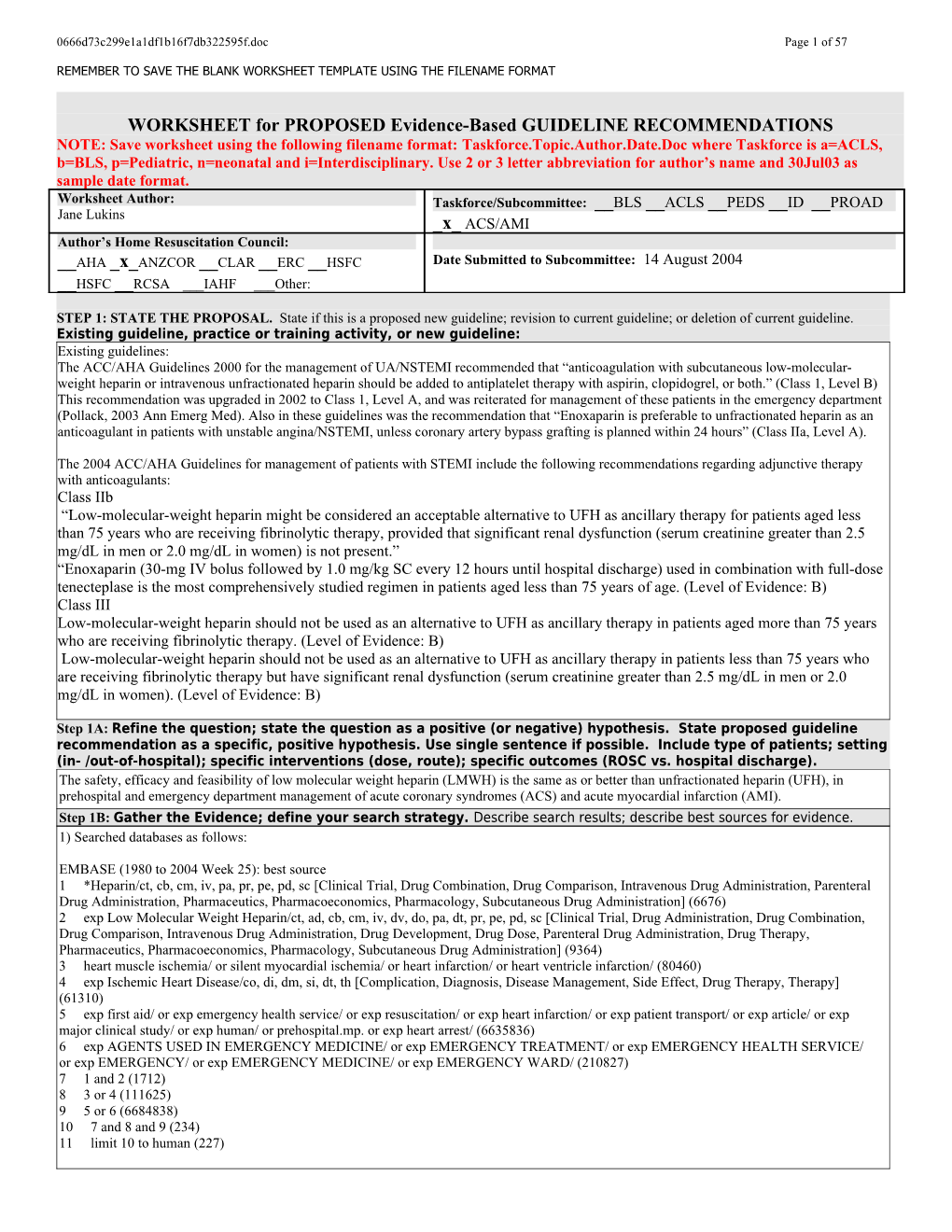

WORKSHEET for PROPOSED Evidence-Based GUIDELINE RECOMMENDATIONS NOTE: Save worksheet using the following filename format: Taskforce.Topic.Author.Date.Doc where Taskforce is a=ACLS, b=BLS, p=Pediatric, n=neonatal and i=Interdisciplinary. Use 2 or 3 letter abbreviation for author’s name and 30Jul03 as sample date format. Worksheet Author: Taskforce/Subcommittee: __BLS __ACLS __PEDS __ID __PROAD Jane Lukins _x_ ACS/AMI Author’s Home Resuscitation Council: __AHA _x_ANZCOR __CLAR __ERC __HSFC Date Submitted to Subcommittee: 14 August 2004 __HSFC __RCSA ___IAHF ___Other:

STEP 1: STATE THE PROPOSAL. State if this is a proposed new guideline; revision to current guideline; or deletion of current guideline. Existing guideline, practice or training activity, or new guideline: Existing guidelines: The ACC/AHA Guidelines 2000 for the management of UA/NSTEMI recommended that “anticoagulation with subcutaneous low-molecular- weight heparin or intravenous unfractionated heparin should be added to antiplatelet therapy with aspirin, clopidogrel, or both.” (Class 1, Level B) This recommendation was upgraded in 2002 to Class 1, Level A, and was reiterated for management of these patients in the emergency department (Pollack, 2003 Ann Emerg Med). Also in these guidelines was the recommendation that “Enoxaparin is preferable to unfractionated heparin as an anticoagulant in patients with unstable angina/NSTEMI, unless coronary artery bypass grafting is planned within 24 hours” (Class IIa, Level A).

The 2004 ACC/AHA Guidelines for management of patients with STEMI include the following recommendations regarding adjunctive therapy with anticoagulants: Class IIb “Low-molecular-weight heparin might be considered an acceptable alternative to UFH as ancillary therapy for patients aged less than 75 years who are receiving fibrinolytic therapy, provided that significant renal dysfunction (serum creatinine greater than 2.5 mg/dL in men or 2.0 mg/dL in women) is not present.” “Enoxaparin (30-mg IV bolus followed by 1.0 mg/kg SC every 12 hours until hospital discharge) used in combination with full-dose tenecteplase is the most comprehensively studied regimen in patients aged less than 75 years of age. (Level of Evidence: B) Class III Low-molecular-weight heparin should not be used as an alternative to UFH as ancillary therapy in patients aged more than 75 years who are receiving fibrinolytic therapy. (Level of Evidence: B) Low-molecular-weight heparin should not be used as an alternative to UFH as ancillary therapy in patients less than 75 years who are receiving fibrinolytic therapy but have significant renal dysfunction (serum creatinine greater than 2.5 mg/dL in men or 2.0 mg/dL in women). (Level of Evidence: B)

Step 1A: Refine the question; state the question as a positive (or negative) hypothesis. State proposed guideline recommendation as a specific, positive hypothesis. Use single sentence if possible. Include type of patients; setting (in- /out-of-hospital); specific interventions (dose, route); specific outcomes (ROSC vs. hospital discharge). The safety, efficacy and feasibility of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is the same as or better than unfractionated heparin (UFH), in prehospital and emergency department management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) and acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Step 1B: Gather the Evidence; define your search strategy. Describe search results; describe best sources for evidence. 1) Searched databases as follows:

EMBASE (1980 to 2004 Week 25): best source 1 *Heparin/ct, cb, cm, iv, pa, pr, pe, pd, sc [Clinical Trial, Drug Combination, Drug Comparison, Intravenous Drug Administration, Parenteral Drug Administration, Pharmaceutics, Pharmacoeconomics, Pharmacology, Subcutaneous Drug Administration] (6676) 2 exp Low Molecular Weight Heparin/ct, ad, cb, cm, iv, dv, do, pa, dt, pr, pe, pd, sc [Clinical Trial, Drug Administration, Drug Combination, Drug Comparison, Intravenous Drug Administration, Drug Development, Drug Dose, Parenteral Drug Administration, Drug Therapy, Pharmaceutics, Pharmacoeconomics, Pharmacology, Subcutaneous Drug Administration] (9364) 3 heart muscle ischemia/ or silent myocardial ischemia/ or heart infarction/ or heart ventricle infarction/ (80460) 4 exp Ischemic Heart Disease/co, di, dm, si, dt, th [Complication, Diagnosis, Disease Management, Side Effect, Drug Therapy, Therapy] (61310) 5 exp first aid/ or exp emergency health service/ or exp resuscitation/ or exp heart infarction/ or exp patient transport/ or exp article/ or exp major clinical study/ or exp human/ or prehospital.mp. or exp heart arrest/ (6635836) 6 exp AGENTS USED IN EMERGENCY MEDICINE/ or exp EMERGENCY TREATMENT/ or exp EMERGENCY HEALTH SERVICE/ or exp EMERGENCY/ or exp EMERGENCY MEDICINE/ or exp EMERGENCY WARD/ (210827) 7 1 and 2 (1712) 8 3 or 4 (111625) 9 5 or 6 (6684838) 10 7 and 8 and 9 (234) 11 limit 10 to human (227)

0666d73c299e1a1df1b16f7db322595f.doc Page 2 of 57

REMEMBER TO SAVE THE BLANK WORKSHEET TEMPLATE USING THE FILENAME FORMAT

MEDLINE (1966 – June week 3 2004): 1 heparin/ and exp heparin, low-molecular-weight/ (1555) 2 myocardial ischemia/ or coronary disease/ or exp angina pectoris/ or exp myocardial infarction/ (212837) 3 1 and 2 (170) 4 limit 3 to human (169) Note: If also tried to combine with Emergency Medicine or Prehospital terms, no articles were found

Cochrane database (CDSR, ACP Journal Club, DARE, CCTR) 1 heparin/ and exp heparin, low-molecular-weight/ (290) 2 myocardial ischemia/ or coronary disease/ or exp angina pectoris/ or exp myocardial infarction/ (10371) 3 1 and 2 (50)

AHA Endnote 7 Master Library 1 searched all fields that contain acute coronary syndrome or myocardial infarction or myocardial ischemia or angina (1453) 2 searched within 1 all fields that contain heparin or low molecular weight heparin or enoxaparin or fraxaparin or dalteparin (150) 3 searched within 2, all fields that contain emergency or prehospital (17)

2) Combined the end results of the above database searches in my own Endnote library where I deleted duplicates. 3) Reviewed titles electronically and deleted those clearly unrelated to question 4) Identified 236 articles. Reviewed abstracts electronically excluded 126 using criteria below. 5) Of 110 articles obtained, 50 were suitable for critical appraisal and inclusion in worksheet. 6) 4 additional articles obtained after initial worksheet completion, 3 were suitable for inclusion in worksheet. Total 53.

List electronic databases searched (at least AHA EndNote 7 Master library [http://ecc.heart.org/], Cochrane database for systematic reviews and Central Register of Controlled Trials [http://www.cochrane.org/], MEDLINE [http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/PubMed/ ], and Embase), and hand searches of journals, review articles, and books. Embase 1980 to 2004 Week 25 Medline 1966 to June Week 3 2004 Cochrane database (reviews and trials) AHA Endnote 7 Master Library Reference lists of articles hand searched to obtain other relevant clinical trials. • State major criteria you used to limit your search; state inclusion or exclusion criteria (e.g., only human studies with control group? no animal studies? N subjects > minimal number? type of methodology? peer-reviewed manuscripts only? no abstract-only studies?)

The searches were limited to human studies, peer and non-peer reviewed manuscripts cited in the world’s literature. Articles excluded were abstract only studies, all narrative reviews and published systematic reviews without a meta-analysis and those that had no relevance to emergency department or prehospital settings (Specifically, in-hospital studies more than 72 hours after patient presentation, post percutaneous angiography trials, trials investigating changes in coagulation factors without clinical end points and long-term outpatient care). • Number of articles/sources meeting criteria for further review: Create a citation marker for each study (use the author initials and date or Arabic numeral, e.g., “Cummins-1”). . If possible, please supply file of best references; EndNote 6+ required as reference manager using the ECC reference library.

Searches narrowed after title/ abstract review to 53 articles

STEP 2: ASSESS THE QUALITY OF EACH STUDY Step 2A: Determine the Level of Evidence. For each article/source from step 1, assign a level of evidence—based on study design and methodology. Level of Definitions Evidence (See manuscript for full details) Level 1 Randomized clinical trials or meta-analyses of multiple clinical trials with substantial treatment effects Level 2 Randomized clinical trials with smaller or less significant treatment effects Level 3 Prospective, controlled, non-randomized, cohort studies Level 4 Historic, non-randomized, cohort or case-control studies Level 5 Case series: patients compiled in serial fashion, lacking a control group Level 6 Animal studies or mechanical model studies Level 7 Extrapolations from existing data collected for other purposes, theoretical analyses Level 8 Rational conjecture (common sense); common practices accepted before evidence-based guidelines 0666d73c299e1a1df1b16f7db322595f.doc Page 3 of 57

REMEMBER TO SAVE THE BLANK WORKSHEET TEMPLATE USING THE FILENAME FORMAT

Step 2B: Critically assess each article/source in terms of research design and methods. Was the study well executed? Suggested criteria appear in the table below. Assess design and methods and provide an overall rating. Ratings apply within each Level; a Level 1 study can be excellent or poor as a clinical trial, just as a Level 6 study could be excellent or poor as an animal study. Where applicable, please use a superscripted code (shown below) to categorize the primary endpoint of each study. For more detailed explanations please see attached assessment form.

Component of Study and Rating Excellent Good Fair Poor Unsatisfactory Design & Highly appropriate Highly appropriate Adequate, Small or clearly Anecdotal, no sample or model, sample or model, design, but biased population controls, off randomized, proper randomized, proper possibly biased or model target end-points controls controls Methods AND OR OR OR OR Outstanding Outstanding accuracy, Adequate under Weakly defensible Not defensible in accuracy, precision, and data the in its class, limited its class, precision, and data collection in its class circumstances data or measures insufficient data collection in its or measures class

A = Return of spontaneous circulation C = Survival to hospital discharge B = Survival of event D = Intact neurological survival E = Other

Step 2C: Determine the direction of the results and the statistics: supportive? neutral? opposed?

DIRECTION of study by results & statistics: SUPPORT the proposal NEUTRAL OPPOSE the proposal Outcome of proposed guideline Outcome of proposed guideline Outcome of proposed guideline Results superior, to a clinically important no different from current inferior to current approach degree, to current approaches approach

Step 2D: Cross-tabulate assessed studies by a) level, b) quality and c) direction (ie, supporting or neutral/ opposing); combine and summarize. Exclude the Poor and Unsatisfactory studies. Sort the Excellent, Good, and Fair quality studies by both Level and Quality of evidence, and Direction of support in the summary grids below. Use citation marker (e.g. author/ date/source). In the Neutral or Opposing grid use bold font for Opposing studies to distinguish them from merely neutral studies. Where applicable, please use a superscripted code (shown below) to categorize the primary endpoint of each study. Supporting Evidence for UA/NSTEMI

The safety, efficacy and feasibility of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is the same as or better than unfractionated heparin (UFH), in prehospital and emergency department management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) and acute myocardial infarction (AMI).

Magee(04)# k,l,s,t Excellent Petersen(04)# e,t,f,s Antman(99; 1)e Antman(99; 2)# e,g,s,t Antman(02)# e Cohen(97) e,t 0666d73c299e1a1df1b16f7db322595f.doc Page 4 of 57

REMEMBER TO SAVE THE BLANK WORKSHEET TEMPLATE USING THE FILENAME FORMAT e c

n Goodman(00; 2) e

d Good e,t Klein(03) f,k,p,s,t

i Campos(02)n,s,t O'Brien(00)i,u, v Goodman(03)

E f,g,e,s,t,v

f o Goodman(00; 1) y t

i e,t Bozovich(00)e,f,g l

a Fair Gurfinkel(95) Brosa(02)i,t u j,g,s,t Detournay(00)i,u

Q Malhotra (01; 1) Mark(98) i,u e,f,g,i,s,t,u Spinler(03)e,t Mattioli(99)e,j,t 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Level of Evidence A = Return of spontaneous circulation B = Survival of event C = Survival to hospital discharge D = Intact neurological survival E = Composite (Death/MI±recurrent angina)F = Major hemorrhage G = Minor hemorrhage H = Bleeding post intervention/surgery I = Cost J = Recurrent ischaemia K = Myocardial Infarction L = Revascularisation M = Thrombotic marker difference N = Composite E + F (incl ICH) O = TIMI flow P = Mortality S = Safety T = Efficacy U = Feasibility V = +G2b3a inhibitor X = STEMI, no reperfusion Y = STEMI + Fibrinolytic therapy Z = STEMI + PCI Citations in italic = studies not performed in ED/Prehospital settings or intervention not initiated within 24 hours of qualifying symptom. * = Trial done in prehospital setting # = Meta-analysis Neutral or Opposing Evidence for UA/NSTEMI The safety, efficacy and feasibility of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is the same as or better than unfractionated heparin (UFH), in prehospital and emergency department management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) and acute myocardial infarction (AMI). e c

n Eikelboom(00)#

e e,f,s,t

d Excellent Berkowitz(01)f i FRAIS

v Ferguson (04) Investigators(99)

E e,t,m,s e,f,s,t f

o Le Nguyen(01)#

y e,f,s,t t i l a u Good Blazing(04)e,f,s, Q Kovar(02)e,f,s,t,v t,v

Cohen(99)v Cohen(02)v,f,g Fair Gurfinkel(99)e,k Klein(97)e,f,g,s, Malhotra(01; Brieger(02)h,s Jones(02)h, t 2)# e,f,g,s,t Clark(00)h,s s Montalescot(03) e,f,g,m,s,t Suvarna(97)j,k,l, t 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Level of Evidence A = Return of spontaneous circulation B = Survival of event C = Survival to hospital discharge D = Intact neurological survival E = Composite (Death/MI±recurrent angina)F = Major hemorrhage 0666d73c299e1a1df1b16f7db322595f.doc Page 5 of 57

REMEMBER TO SAVE THE BLANK WORKSHEET TEMPLATE USING THE FILENAME FORMAT

G = minor hemorrhage H = Bleeding post intervention/surgery I = Cost J = Recurrent ischaemia K = Myocardial Infarction (outcome) L = Revascularisation M = Thrombotic marker difference N = Composite E + F (incl ICH) P = Mortality S = Safety T = Efficacy U = Feasibility V = +G2b3a inhibitor X = STEMI, no reperfusion Y = STEMI + Fibrinolytic therapy Z = STEMI + PCI Citations in italic = studies not performed in ED/Prehospital settings or intervention not initiated within 24 hours of qualifying symptom. * = Trial done in prehospital setting # = Meta-analysis

Supporting Evidence for STEMI

The safety, efficacy and feasibility of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is the same as or better than unfractionated heparin (UFH), in prehospital and emergency department management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) and acute myocardial infarction (AMI). e c n e

d Excellent Theroux(03)# Wallentin(03; 2)* i e,j,k,t,f,g,s,y e,t,u,y,s v E

f o

y t i

l Baird(02)*e,y

a Good Van deWerf Wallentin(03; 1) Klein(03) u (01)e,j,k,l,n,s,t, k,o,s,t,y f,p,s,t Q y

Fair Cohen(00)e,t,x

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Level of Evidence A = Return of spontaneous circulation B = Survival of event C = Survival to hospital discharge D = Intact neurological survival E = Composite (Death/MI±recurrent angina)F = Major hemorrhage G = minor hemorrhage H = Bleeding post intervention/surgery I = Cost J = Recurrent ischaemia K = Myocardial Infarction (outcome) L = Revascularisation M = Thrombotic marker difference N = Composite E + F (incl ICH) O = TIMI flow P = Mortality S = Safety T = Efficacy U = Feasibility V = +G2b3a inhibitor X = STEMI, no reperfusion Y = STEMI + Fibrinolytic therapy Z = STEMI + PCI Citations in italic = studies not performed in ED/Prehospital settings or intervention not initiated within 6 hours of STEMI onset. * = Trial done in prehospital setting # = Meta-analysis Neutral or Opposing Evidence for STEMI The safety, efficacy and feasibility of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is the same as or better than unfractionated heparin (UFH), in prehospital and emergency department management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) and acute myocardial infarction (AMI). 0666d73c299e1a1df1b16f7db322595f.doc Page 6 of 57

REMEMBER TO SAVE THE BLANK WORKSHEET TEMPLATE USING THE FILENAME FORMAT e c n e

d Excellent Cohen(03)e,s,x i v E

f o

y t i l

a Good Kovar(02)e,f,s,t,

u Ross(01)s,t,y v Q

Fair Peters(01)f,s,y Dubois(03)s,t,y,z

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Level of Evidence A = Return of spontaneous circulation B = Survival of event C = Survival to hospital discharge D = Intact neurological survival E = Composite (Death/MI±recurrent angina)F = Major hemorrhage G = minor hemorrhage H = Bleeding post intervention/surgery I = Cost J = Recurrent ischaemia K = Myocardial Infarction (outcome) L = Revascularisation M = Thrombotic marker difference N = Composite E + F (incl ICH) P = Mortality S = Safety T = Efficacy U = Feasibility V = +G2b3a inhibitor X = STEMI, no reperfusion Y = STEMI + Fibrinolytic therapy Z = STEMI + PCI Citations in italic = studies not performed in ED/Prehospital settings or intervention not initiated within 6 hours of STEMI onset. * = Trial done in prehospital setting # = Meta-analysis

STEP 3. DETERMINE THE CLASS OF RECOMMENDATION. Select from these summary definitions. CLASS CLINICAL DEFINITION REQUIRED LEVEL OF EVIDENCE Class I • Always acceptable, safe • One or more Level 1 studies are present (with rare Definitely recommended. Definitive, • Definitely useful exceptions) excellent evidence provides support. • Proven in both efficacy & effectiveness • Study results consistently positive and compelling • Must be used in the intended manner for proper clinical indications. Class II: • Safe, acceptable • Most evidence is positive Acceptable and useful • Clinically useful • Level 1 studies are absent, or inconsistent, or lack • Not yet confirmed definitively power • No evidence of harm • Class IIa : Acceptable and useful • Safe, acceptable • Generally higher levels of evidence Good evidence provides support • Clinically useful • Results are consistently positive • Considered treatments of choice • Class IIb: Acceptable and useful • Safe, acceptable • Generally lower or intermediate levels of evidence Fair evidence provides support • Clinically useful • Generally, but not consistently, positive results • Considered optional or alternative treatments Class III: • Unacceptable • No positive high level data Not acceptable, not useful, may be • Not useful clinically • Some studies suggest or confirm harm. harmful • May be harmful. • Research just getting started. • Minimal evidence is available Indeterminate • Continuing area of research • Higher studies in progress • No recommendations until • Results inconsistent, contradictory further research • Results not compelling 0666d73c299e1a1df1b16f7db322595f.doc Page 7 of 57

REMEMBER TO SAVE THE BLANK WORKSHEET TEMPLATE USING THE FILENAME FORMAT

STEP 3: DETERMINE THE CLASS OF RECOMMENDATION. State a Class of Recommendation for the Guideline Proposal. State either a) the intervention, and then the conditions under which the intervention is either Class I, Class IIA, IIB, etc.; or b) the condition, and then whether the intervention is Class I, Class IIA, IIB, etc. Indicate if this is a __Condition or _x_Intervention The safety, efficacy and feasibility of low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is the same as or better than unfractionated heparin (UFH), in prehospital and emergency department management of acute coronary syndromes (ACS) and acute myocardial infarction (AMI). Final Class of recommendation: __Class I-Definitely Recommended __Class IIa-Acceptable & Useful; good evidence __Class IIb-Acceptable & Useful; fair evidence __Class III – Not Useful; may be harmful __Indeterminate-minimal evidence or inconsistent

Treatment Recommendations DRAFT FOR DISCUSSION WITH THE TASK FORCE DALLAS 2005:

UFH versus LMWH in UA/NSTEMI Emergency department administration of LMWH compared to UFH for patients with UA/NSTEMI may be helpful in addition to antiplatelet therapy with aspirin, however it is unknown at what time period after the onset of symptoms it is optimal and if it should be standard practice for ED physicians to provide this medical intervention in the ED based on the current science. There is currently no evidence to suggest that treatment with LMWH in UA/NSTEMI is time critical so use in the prehospital setting is not recommended.

UFH versus LMWH in STEMI In the prehospital and early emergency department settings, administration of LMWH for patients with STEMI might be considered an acceptable alternative to UFH as ancillary therapy for patients aged less than 75 years who are receiving fibrinolytic therapy, provided that significant renal dysfunction (serum creatinine greater than 2.5 mg/dL in men or 2.0 mg/dL in women) is not present. UFH is recommended for patients aged 75 years or older as ancillary therapy to fibrinolysis in this setting. In patients with STEMI who are not receiving fibrinolysis, LMWH (specifically enoxaparin) might be considered an acceptable alternative to UFH in the emergency department setting.

REVIEWER’S PERSPECTIVE AND POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: Briefly summarize your professional background, clinical specialty, research training, AHA experience, or other relevant personal background that define your perspective on the guideline proposal. List any potential conflicts of interest involving consulting, compensation, or equity positions related to drugs, devices, or entities impacted by the guideline proposal. Disclose any research funding from involved companies or interest groups. State any relevant philosophical, religious, or cultural beliefs or longstanding disagreements with an individual. Dr. Jane Lukins is credentialed in Emergency Medicine by the Australasian College of Emergency Medicine. She completed an Emergency Medical Services fellowship at University of Toronto, Canada. Dr. Lukins has no financial conflicts of interest involving consulting, compensation or equity positions related to drugs, devices, or entities impacted by the guideline process, or any research funding from involved companies or interest groups. She does not have any relevant intellectual biases. She does not have any relevant philosophical, religious, or cultural beliefs or longstanding disagreements with an individual.

REVIEWER’S FINAL COMMENTS AND ASSESSMENT OF BENEFIT / RISK: Summarize your final evidence integration and the rationale for the class of recommendation. Describe any mismatches between the evidence and your final Class of Recommendation. “Mismatches” refer to selection of a class of recommendation that is heavily influenced by other factors than just the evidence. For example, the evidence is strong, but implementation is difficult or expensive; evidence weak, but future definitive evidence is unlikely to be obtained. Comment on contribution of animal or mechanical model studies to your final recommendation. Are results within animal studies homogeneous? Are animal results consistent with results from human studies? What is the frequency of adverse events? What is the possibility of harm? Describe any value or utility judgments you may have made, separate from the evidence. For example, you believe evidence-supported interventions should be limited to in-hospital use because you think proper use is too difficult for pre-hospital providers. Please include relevant key figures or tables to support your assessment. 0666d73c299e1a1df1b16f7db322595f.doc Page 8 of 57

REMEMBER TO SAVE THE BLANK WORKSHEET TEMPLATE USING THE FILENAME FORMAT

UFH versus LMWH in UA/NSTEMI Consensus on Science Extrapolation from 7 in-hospital RCTs (LOE 1 and 2) and additional studies (including 7 meta-analyses) which document similar or improved composite outcomes after administration of LMWH, compared with UFH, to patients with UA/NSTEMI within the first 48 hours after symptom onset suggests (LOE 7) that earlier administration of LMWH to patients in the ED may improve outcomes. Extrapolation to the prehospital setting is difficult as often the diagnosis of UA/NSTEMI is not yet clear.

Efficacy There are two excellent in-hospital LOE 1 trials that have shown superiority of the LMWH Enoxaparin, over UFH, in terms of efficacy, TIMI 11B and ESSENCE (Antman 1999; 1 and Cohen 1997), both show a reduction in the composite of death, MI and urgent revascularisation occurring in the acute phase (8 to 14 days) and continuing to the longer term (30 to 43 days). 1 year follow up shows this reduction is sustained. A meta-analysis of the results of these two trials (Antman 1999; 2) and another meta- analysis of the one-year follow up data from the 2 trials (Antman 2002) have also confirmed that enoxaparin significantly reduces the triple composite outcome of death, MI, and recurrent ischaemia needing urgent revascularisation to one year. However, in the largest trial, SYNERGY (Ferguson 2004), which included an early invasive strategy, there was no difference in efficacy between the LMWH Enoxaparin and UFH.

Large trials comparing other LMWHs to UFH have shown no difference in terms of efficacy, between the two anticoagulants, no trials have shown LMWH to be inferior to UFH in terms of efficacy. Three meta-analyses have been done comparing trials of different LMWHs and UFH (Eikelbloom 2000, Le Nguyen 2001 and Magee 2004). Eiklebloom and Le Nguyen found no statistically significant difference in efficacy between LMWH and UFH, although there was a 12% and 14% reduction respectively for the composite outcome of death and MI with LMWH. While Magee also found no difference in overall mortality between LMWH and UFH (OR = 1.0), there was a significant reduction in the occurrence of MI and need for revascularisation procedures (OR = 0.83 and 0.88 respectively).

Safety In the SYNERGY trial (Ferguson 2004) there was modest excess of major bleeding found in the LMWH Enoxaparin group compared to the UFH group. Other trials, however, have not found major bleeding events to be significantly different with LMWH compared to UFH,but have consistently shown an increase in minor bleeding, usually reported as ecchymoses at injection sites, with the use of LMWH.

A Mexican trial (Campos 2002) showed a superior safety profile using a lower dose of enoxaparin (0.8mg/kg/dose) when compared to UFH, while retaining the therapeutic effect and efficacy benefit of the LMWH.

With regard to safety of LMWH compared to UFH in the setting of angiography; Breiger (2002) concluded that omission of LMWH (enoxaparin) on the morning of angiography resulted in vascular complication rates comparable to that of UFH. One trial studying patients undergoing CABGs found a significant increase in post-operative bleeding complications in patients given LMWH (fragmin) within 12 hours of surgery, compared to those who received LMWH more than 12 hours prior to surgery or those being treated with UFH (Clark 2000), and another trial found there was an increased rate of re-exploration for post-op bleeding in patients who had received LMWH (Enoxaparin) within 48 hours of cardiac surgery (Jones 2002).

Feasibility It is well recognised that the twice daily subcutaneous dosing of LMWH is superior in terms of ease of administration in comparison to the intravenous infusion and APTT monitoring required with UFH. The authors of the SYNERGY trial (Ferguson 2004) concluded that “the advantages of convenience should be balanced with the modest excess of major bleeding”.

There have also been several cost analysis studies comparing the anticoagulants in different countries (done as subsets of the ESSENCE and TIMI 11B trials). All have shown an overall cost benefit to health systems in favour of LMWH, mainly due to a decrease in the need for revascularisation procedures. (O’Brien 2000, Brosa 2002, Detournay 2000, Mark 1998).

With regard to the timing of treatment with anticoagulation in patients with UA/NSTEMI there has been no time dependant caveat reported in the literature and although common sense would suggest treatment begin as soon as the condition is recognised, this requires ECG interpretation capability. For this reason it may not be feasible to use UFH or LMWH in the prehospital setting unless long out-of hospital times are expected and ECG capability is present. This could be an area that requires dedicated trials.

Crossover of anti-thrombin therapy Two recent trials comparing the LMWH, Enoxaparin, to UFH (Blazing 2004, Ferguson 2004) have included patients who received anti-thrombin therapy prior to randomization, meaning some patients had a crossover of anti-thrombin therapy. Both of these trials demonstrated neutral efficacy and one documented opposing safety for Enoxaparin compared to UFH. The meta-analysis by 0666d73c299e1a1df1b16f7db322595f.doc Page 9 of 57

REMEMBER TO SAVE THE BLANK WORKSHEET TEMPLATE USING THE FILENAME FORMAT

Petersen 2004 (LOE 1) documented an increased benefit for the combined efficacy outcome in those patients treated with Enoxaparin compared to UFH who did not receive pre-randomisation therapy (number needed to treat = 72). This was compared to the total study population, including patients receiving crossover therapy, where the number needed to treat was 107. The authors theorise that crossover of anti-thrombin therapy may attenuate a benefit of Enoxaparin if anti-thrombin effects fall during crossover, or may increase the risk of bleeding, if anti-thrombin effects rise. Therefore, crossover of antithrombin therapy is not recommended.

In combination with G2b3a Inhibitors Five trials have compared UFH and LMWH in patients with NSTEMI who were treated with a G2b3a inhibitor (Blazing 2004, Goodman 2003, Cohen 2002, Kovar 2002, Cohen 1999). In terms of efficacy, LMWHs compared favourably or were non inferior to UFH, and in terms of safety, there were similar or less frequent major bleeding events with LMWH, but again an increased frequency of minor bleeding complications defined as cutaneous (ecchymoses at injection or catheterization sites) or oropharyngeal (mostly epistaxis).

In the Emergency Department setting There are no trials specifically done in the prehospital or very early ED setting (first 4 hours from presentation in the ED). However, as many patients with UA/NSTEMI may call 911 or present to the Emergency Department up to 24 hours after the onset of symptoms, it is reasonable to draw efficacy conclusions from trials that have been conducted in other settings (eg inpatient/cardiology) if the time from qualifying symptoms to initiation of intervention is within 24 hours. The TIMI 11B trial (LOE 1, Antman 99; 1) reported a median time of 11 hours from qualifying symptom to first dose of study medication, which places it in a time frame relevant to ED. Unfortunately, this time interval is rarely reported in the literature and in its place, the time to randomisation from qualifying symptom is more commonly reported. This time interval can be used as a surrogate recognising that delays from randomisation to time of treatment can occur. Thus, this surrogate interval will underestimate the actual time to treatment. In the trial by Gurfinkel (1995) there was a mean time of 6 hours from qualifying symptoms to randomisation, FRAXIS (FRAIS investigators 1999) reported that 53% of patients were randomised within 6 hours of symptoms, SYNERGY (LOE 2, Ferguson 2004) had a median time of 14.7 hours from symptom onset to enrollment and the trial by Survana (1997) randomised patients within 24 hours of symptoms. Of these trials, TIMI 11B (LOE 1, Antman 1999; 1) and Gurfinkel 1995 (LOE 2) are supportive of LMWH compared to UFH in terms of efficacy, the others are neutral.

It should be noted that although the ESSENCE trial (LOE 1, Cohen 1997) randomised patients within 24 hours of the qualifying symptom, it was reported that 96% received the study medication within 12 hours of randomisation (which could mean up to 36 hours from symptom onset). There were four other trials that randomised patients within 48 to 72 hours of qualifying symptoms (Montalescot 2003, Mattoli 1999, Klein 1997 and Malhotra 2001; 1). These trials are therefore less relevant, and the evidence that they provide must be extrapolated to the ED setting.

Given this, it can be recommended that high risk patients with UA/NSTEMI (those with a clear history of unstable angina, a known significant past history of coronary artery disease or ischaemic ECG changes, or those with a cardiac enzyme rise) should be treated with LMWH (Enoxaparin) in preference to UFH as soon as the condition is realised, as long as CABG surgery is not planned within 24 hours. (Class 11b)

It is also recommended that future trials should attempt to define whether there is a time critical benefit to anticoagulation therapy in UA/NSTEMI and that it should be standard to measure and report the time interval from qualifying symptom to intervention.

In the Prehospital setting There are no trials comparing UFH and LMWH in the prehospital setting for UA/NSTEMI. There is also no evidence to suggest that treatment with an anticoagulant in UA/NSTEMI is time critical (such has been established with reperfusion in STEMI). Therefore, the use of an anticoagulant in most prehospital settings for UA/NSTEMI is not recommended. (Class Indeterminate)

UFH versus LMWH in STEMI Consensus on Science Evidence from 3 RCTs (LOE 1 and 2) and additional studies (LOE 1 to 7, including one meta-analysis) document improvement in overall TIMI flow and ischaemic outcomes when LMWH (specifically enoxaparin), compared to UFH, is administered to patients with STEMI in the early hospital setting (within 6 hours of symptom onset).

In the prehospital setting, 2 RCTs (LOE 1 and 2) document improvement in composite outcomes when LMWH (specifically enoxaparin), compared to UFH, is administered as to patients with STEMI as adjunctive therapy to fibrinolysis.

In the Emergency Department setting 0666d73c299e1a1df1b16f7db322595f.doc Page 10 of 57

REMEMBER TO SAVE THE BLANK WORKSHEET TEMPLATE USING THE FILENAME FORMAT

STEMI is a time critical medical condition and trials that have been conducted in the hospital setting have randomised patients within the first 6 hours of symptom onset, this makes them relevant to the ED setting. In-hospital trials in patients with STEMI have compared UFH and LMWH as ancillary treatment with fibrinolysis, during PCI and also in the case where revascularisation is not an option. In combination with Fibrinolytic agents, in terms of efficacy the LMWHs, have been found to be superior to, or as good as UFH in terms of overall TIMI flow (Wallentin 2003; 1, Ross 2001) and also in reducing the frequency of ischaemic complications (Van de Werf 2001), with a trend to a 14% reduction in mortality in a meta-analysis (Theroux 2003). In terms of safety, trials have conflicting results. Some trials have shown no difference (Wallentin 2003; 1 and Ross 2001), ASSENT-3 found the combined efficacy and safety outcome to be in favour of enoxaparin (Van de Werf 2001), but the meta-analysis showed significantly more bleeding complications (major and minor) with Enoxaparin compared to UFH (Theroux 2003). When revascularization is not an option (eg: late presentation, contraindication) one LOE 1 trial showed a similar safety and efficacy profile of LMWH (enoxaparin) to UFH (Cohen 2003).

Therefore, in the early ED setting it is recommended that LMWH (specifically enoxaparin) might be considered an acceptable alternative to UFH as ancillary therapy for patients aged less than 75 years who are receiving fibrinolytic therapy, provided that significant renal dysfunction (serum creatinine greater than 2.5 mg/dL in men or 2.0 mg/dL in women) is not present. (Class IIb) In patients with STEMI who are not receiving fibrinolysis, LMWH (specifically enoxaparin) might be considered an acceptable alternative to UFH. (Class Indeterminate)

In the Prehospital setting Two trials comparing UFH to LMWH as ancillary treatment with fibrinolysis have been conducted in the prehospital setting (Baird 2002 and Wallentin 2003; 2). In the trial by Baird 43% of patients were treated in the prehospital setting by physicians, in ASSENT-3 Plus (Wallentin 2003; 2) all patients were treated in the prehospital setting by physicians, or by nurses or paramedics with on-line medical control.

Both trials used Enoxaparin as the LMWH and showed superiority in terms of efficacy compared to UFH.

In terms of safety, the Baird trial showed no difference in major bleeding complications, however there was a concerning increase in intracranial hemorrhage in patients > 75 years receiving Enoxaparin in ASSENT–3 Plus. This serious adverse event led to the conclusion in the ASSENT-3 Plus trial that (at least with tenecteplase) UFH is recommended for the prehospital setting. The results of trials investigating a decreased dose of enoxaparin in those older than 75 years are needed to help define the safety profile of Enoxaparin before it can be recommended in this age group.

In terms of feasibility, a cost analysis showed treatment with LMWH to be cheaper in the acute phase (Baird 2002) and in ASSENT-3 Plus patients received reperfusion therapy 47 minutes faster than compared with the in-hospital parallel trial (Van Der Werf 2002) and more patients had received the full dose of enoxaparin compared to UFH by the time they reached the hospital.

Therefore, in the Prehospital environment LMWH (specifically enoxaparin) might be considered an acceptable alternative to UFH as ancillary therapy for patients aged less than 75 years who are receiving fibrinolytic therapy, provided that significant renal dysfunction (serum creatinine greater than 2.5 mg/dL in men or 2.0 mg/dL in women) is not present. (Class Indeterminate) UFH is recommended for patients aged 75 years or older as ancillary therapy to fibrinolysis in this setting. (Class I)

Preliminary draft/outline/bullet points of Guidelines revision: Include points you think are important for inclusion by the person assigned to write this section. Use extra pages if necessary. UFH versus LMWH in UA/NSTEMI Previous Recommendations From the previous ACC/AHA Guidelines 2000 for the management of UA/NSTEMI it was recommended that “anticoagulation with subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin or intravenous unfractionated heparin should be added to antiplatelet therapy with aspirin, clopidogrel, or both.” (Class 1, Level B) This recommendation was upgraded in 2002 to Class 1, Level A, and was reiterated for management of these patients in the emergency department (Pollack, 2003 Ann Emerg Med). Also in these guidelines was the recommendation that “Enoxaparin is preferable to unfractionated heparin as an anticoagulant in patients with unstable angina/NSTEMI, unless coronary artery bypass grafting is planned within 24 hours” (Class IIa, Level A).

CoSTR Statement DRAFT FOR DISCUSSION WITH THE TASK FORCE DALLAS 2005: Consensus on Science Extrapolation from 7 in-hospital RCTs (LOE 1 and 2) and additional studies (including 7 meta-analyses) which document similar or improved composite outcomes after administration of LMWH, compared with UFH, to patients with UA/NSTEMI within the 0666d73c299e1a1df1b16f7db322595f.doc Page 11 of 57

REMEMBER TO SAVE THE BLANK WORKSHEET TEMPLATE USING THE FILENAME FORMAT

first 48 hours after symptom onset suggests (LOE 7) that earlier administration of LMWH to patients in the ED may improve outcomes. Extrapolation to the prehospital setting is difficult as often the diagnosis of UA/NSTEMI is not yet clear.

Treatment Recommendation Therefore, emergency department administration of LMWH compared to UFH for patients with UA/NSTEMI may be helpful in addition to antiplatelet therapy with aspirin, however it is unknown at what time period after the onset of symptoms it is optimal and if it should be standard practice for ED physicians to provide this medical intervention in the ED based on the current science. There is currently no evidence to suggest that treatment with LMWH in UA/NSTEMI is time critical so use in the prehospital setting is not recommended.

UFH versus LMWH in STEMI Recent Guidelines The 2004 ACC/AHA Guidelines for management of patients with STEMI include the following recommendations regarding adjunctive therapy with anticoagulants: Class IIb “Low-molecular-weight heparin might be considered an acceptable alternative to UFH as ancillary therapy for patients aged less than 75 years who are receiving fibrinolytic therapy, provided that significant renal dysfunction (serum creatinine greater than 2.5 mg/dL in men or 2.0 mg/dL in women) is not present.” “Enoxaparin (30-mg IV bolus followed by 1.0 mg/kg SC every 12 hours until hospital discharge) used in combination with full- dose tenecteplase is the most comprehensively studied regimen in patients aged less than 75 years of age. (Level of Evidence: B) Class III Low-molecular-weight heparin should not be used as an alternative to UFH as ancillary therapy in patients aged more than 75 years who are receiving fibrinolytic therapy. (Level of Evidence: B) Low-molecular-weight heparin should not be used as an alternative to UFH as ancillary therapy in patients less than 75 years who are receiving fibrinolytic therapy but have significant renal dysfunction (serum creatinine greater than 2.5 mg/dL in men or 2.0 mg/dL in women). (Level of Evidence: B)

CoSTR Statement DRAFT FOR DISCUSSION WITH THE TASK FORCE DALLAS 2005: Consensus on Science Evidence from 3 RCTs (LOE 1 and 2) and additional studies (LOE 1 to 7, including one meta-analysis) document improvement in overall TIMI flow and ischaemic outcomes when LMWH (specifically enoxaparin), compared to UFH, is administered to patients with STEMI in the early hospital setting (within 6 hours of symptom onset).

In the prehospital setting, 2 RCTs (LOE 1 and 2) document improvement in composite outcomes when LMWH (specifically enoxaparin), compared to UFH, is administered to patients with STEMI as adjunctive therapy to fibrinolysis. This however, must be balanced against the risk of serious adverse events, specifically of an increase in intracranial hemorrhage in patients > 75 years receiving LMWH (Enoxaparin) documented in one of these RCTs (LOE 2).

Treatment Recommendation Therefore, in the prehospital and early emergency department settings, administration of LMWH for patients with STEMI might be considered an acceptable alternative to UFH as ancillary therapy for patients aged less than 75 years who are receiving fibrinolytic therapy, provided that significant renal dysfunction (serum creatinine greater than 2.5 mg/dL in men or 2.0 mg/dL in women) is not present. UFH is recommended for patients aged 75 years or older as ancillary therapy to fibrinolysis in this setting. In patients with STEMI who are not receiving fibrinolysis, LMWH (specifically enoxaparin) might be considered an acceptable alternative to UFH in the emergency department setting.

Publication: Chapter: Pages:

Topic and subheadings:

UFH versus LMWH in UA/NSTEMI Safety 0666d73c299e1a1df1b16f7db322595f.doc Page 12 of 57

REMEMBER TO SAVE THE BLANK WORKSHEET TEMPLATE USING THE FILENAME FORMAT

Efficacy Feasibility Crossover of antithrombin therapy In combination with G2b3a Inhibitors In the Emergency Department setting In the Prehospital setting

UFH versus LMWH in STEMI In the Prehospital setting: Safety, efficacy, and feasibility In the Emergency Department setting In combination with Fibrinolytic agents In combination with diagnostic angiography and PCI When revascularization is not an option (eg: late presentation, contraindication)

Attachments: . Bibliography in electronic form using the Endnote Master Library. It is recommended that the bibliography be provided in annotated format. This will include the article abstract (if available) and any notes you would like to make providing specific comments on the quality, methodology and/or conclusions of the study. 0666d73c299e1a1df1b16f7db322595f.doc Page 13 of 57

REMEMBER TO SAVE THE BLANK WORKSHEET TEMPLATE USING THE FILENAME FORMAT Citation List

Citation Marker Full Citation* Antman 1999; 1 Antman, E. M., C. H. McCabe, et al. (1999). "Enoxaparin prevents death and cardiac ischemic events in unstable angina/non-Q-wave myocardial infarction. Results of the thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) 11B trial." Circulation 100(15): 1593-1601. BACKGROUND: Low-molecular-weight heparins are attractive alternatives to unfractionated heparin (UFH) for management of unstable angina/non-Q-wave myocardial infarction (UA/NQMI). METHODS AND RESULTS: Patients (n=3910) with UA/NQMI were randomized to intravenous UFH for >/=3 days followed by subcutaneous placebo injections or uninterrupted antithrombin therapy with enoxaparin during both the acute phase (initial 30 mg intravenous bolus followed by injections of 1.0 mg/kg every 12 hours) and outpatient phase (injections every 12 hours of 40 mg for patients weighing <65 kg and 60 mg for those weighing >/=65 kg). The primary end point (death, myocardial infarction, or urgent revascularization) occurred by 8 days in 14.5% of patients in the UFH group and 12.4% of patients in the enoxaparin group (OR 0.83; 95% CI 0.69 to 1.00; P=0. 048) and by 43 days in 19.7% of the UFH group and 17.3% of the enoxaparin group (OR 0.85; 95% CI 0.72 to 1.00; P=0.048). During the first 72 hours and also throughout the entire initial hospitalization, there was no difference in the rate of major hemorrhage in the treatment groups. During the outpatient phase, major hemorrhage occurred in 1.5% of the group treated with placebo and 2.9% of the group treated with enoxaparin (P=0.021). CONCLUSIONS: Enoxaparin is superior to UFH for reducing a composite of death and serious cardiac ischemic events during the acute management of UA/NQMI patients without causing a significant increase in the rate of major hemorrhage. No further relative decrease in events occurred with outpatient enoxaparin treatment, but there was an increase in the rate of major hemorrhage.

TIMI 11B Trial. Multicentre, double blind, randomised controlled trial Hypothesis: to test if LMWH (Enoxaparin) was superior to UFH in patients with unstable angina/Non-STEMI. Enoxaparin given as initial 30mg IV bolus, them 1mg/kg subcutaneously) in the acute phase (first 8 days) and if an extended outpatient course (to 43 days) provided benefit. Primary end points: For efficacy were a composite of all cause mortality, recurrent MI, or urgent revascularisation. For safety, major hemorrhage. Secondary end points: Looked at subgroup outcomes and minor hemorrhage. Outcomes at 48hrs and 14 days also looked at. N=3910 pts, groups were similar. Time from qualifying symptom (>5 mins ischaemic discomfort at rest) to first dose of study medication: median 11 hours (5.8, 18.9). Enoxaparin found to be superior in acute phase, max benefit at 48 hrs, with no increase in major hemorrhage, but an increase in incidence of minor hemorrhage (injection site or sheath site hematoma). No continued benefit in outpatient phase but an increased incidence of major hemorrhage. Drug company sponsored the trial (declared).

Level of Evidence: 1 Quality of Evidence: Excellent in design and methodology, Excellent in terms of appropriateness to ED setting. Direction of Evidence: Supportive of LMWH (enoxaparin) over UFH in terms of efficacy and neutral for safety in the acute phase. (Commencing treatment within 24 hours symptom onset)

Antman 1999; 2 Antman, E. M., M. Cohen, et al. (1602). "Assessment of the treatment effect of enoxaparin for unstable angina/non-Q-wave myocardial infarction: TIMI 11B-essence meta-analysis." Circulation 100(15): 1602-1608. Background - Two phase III trials of enoxaparin for unstable angina/non- Q-wave myocardial infarction have shown it to be superior to unfractionated heparin for preventing a composite of death and cardiac ischemic events. A prospectively planned meta-analysis was performed to provide a more precise estimate of the effects of enoxaparin on multiple end points. Methods and Results - Event rates for death, the composite end points of death/nonfatal myocardial infarction and death/nonfatal myocardial infarction/urgent revascularization, and major hemorrhage were extracted from the TIMI 11B and ESSENCE databases. Treatment effects at days 2, 8, 14, and 43 were expressed as the OR (and 95% CI) for enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin. All heterogeneity tests for 0666d73c299e1a1df1b16f7db322595f.doc Page 14 of 57

REMEMBER TO SAVE THE BLANK WORKSHEET TEMPLATE USING THE FILENAME FORMAT

efficacy end points were negative, which suggests comparability of the findings in TIMI 11B and ESSENCE. Enoxaparin was associated with a 20% reduction in death and serious cardiac ischemic events that appeared within the first few days of treatment, and this benefit was sustained through 43 days. Enoxaparin's treatment benefit was not associated with an increase in major hemorrhage during the acute phase of therapy, but there was an increase in the rate of minor hemorrhage (OR 2.38; 95% CI 1.98 to 2.85; p<0.0001). Conclusions - The accumulated evidence, coupled with the simplicity of subcutaneous administration and elimination of the need for anticoagulation monitoring, indicates that enoxaparin should be considered as a replacement for unfractionated heparin as the antithrombin for the acute phase of management of patients with high-risk unstable angina/non-Q-wave myocardial infarction.

Meta-analysis of ESSENCE and TIMI 11B trials. Trials selected for intervention with enoxaparin as the LMWH intervention group. Minor hemorrhage was not defined in this trial. Level of Evidence: 1 Quality of Evidence: Excellent Direction of Evidence: Supportive for efficacy of LMWH (Enoxaparin) v UFH, with treatment effect occurring within 48 hours and persisting out to day 43. Opposing for safety with minor hemorrhage only increased significantly with LMWH. Antman 2002 Antman, E. M., M. Cohen, et al. (2002). "Enoxaparin is superior to unfractionated heparin for preventing clinical events at 1-year follow-up of TIMI 11B and ESSENCE." European Heart Journal 23(4): 308-314. Background: Enoxaparin treatment is associated with a 20% reduction in clinical events during the acute phase of management of patients with unstable angina/non ST elevation myocardial infarction. Interest in the use of enoxaparin would be enhanced further if evidence of a durable treatment benefit over the long term could be provided. Methods: Event rates at 1 year for the composite end-point of death/non-fatal myocardial infarction/urgent revascularization and its individual components were ascertained from the TIMI 11B and ESSENCE databases. Results: There was no evidence of heterogeneity between TIMI 11B and ESSENCE in tests for interactions between treatment and trial. A significant treatment benefit of enoxaparin on the rate of death/non-fatal myocardial infarction/urgent revascularization was observed at 1 year (hazard ratio 0.88, P=0.008). The event rate was 25.8% in the unfractionated heparin group and 23.3% in the enoxaparin group, an absolute difference of 2.5%. A progressively greater treatment benefit of enoxaparin was observed as the level of patient risk at baseline increased. Treatment effects for the individual end-point elements ranged from 9-14%, favouring enoxaparin. Conclusions: The stable absolute difference in event rates of 2.5% seen at 8 days and again at 1 year favouring enoxaparin may be due to more effective control of the thrombotic process surrounding the index event. Once the pharmacological effect of enoxaparin had dissipated there was no rebound increase in events. Thus, those patients who had received enoxaparin acutely were protected from experiencing a deterioration of the original therapeutic benefit. These findings regarding enoxaparin add to the data to be considered by clinicians when selecting an antithrombin for the acute phase of management of unstable angina/non-ST elevation myocardial infarction. (C) 2001 The European Society of Cardiology.

Prospective meta-analysis of 1 year follow up data of TIMI 11B and ESSENCE trials. Hypothesis: Treatment effect of enoxaparin given in the acute phase for unstable angina/Non- STEMI would be sustained at 1 year. N=6646 available for follow up of 7081 originally enrolled in the 2 trials (94%). Outcomes: Individual events of death, MI, urgent revascularisation, and composite of death and MI, and triple composite. Patients with 0–2 risk factors were combined into a low risk stratum (32%), those with 3–4 risk factors into an intermediate risk stratum (56%), and 5–7 risk factors into a high risk stratum (12%), based on the following TIMI Risk Factors • Age >65 y • Documented prior coronary artery stenosis >50% • Three or more conventional cardiac risk factors (eg, age, sex, family history, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, smoking, hypertension, obesity) • Use of aspirin in the preceding 7 d • Two or more anginal events in the preceding 24 h • ST-segment deviation (transient elevation or persistent depression) 0666d73c299e1a1df1b16f7db322595f.doc Page 15 of 57

REMEMBER TO SAVE THE BLANK WORKSHEET TEMPLATE USING THE FILENAME FORMAT

• Increased cardiac biomarkers The 8 day benefit of enoxaparin was sustained at 1 year for the triple composite outcome and increased as the baseline risk for heart disease increased. A statistically significant treatment benefit of enoxaparin was observed in the intermediate (hazard ratio 0·87; 95% CI 0·77, 0·99; P=0·04) and high risk (hazard ratio 0·80; 95% CI 0·65, 0·98; P=0·03) groups.

Level of Evidence: 1 Quality of Evidence: Excellent design and methodology, appropriateness to ED setting is Good. Direction of Evidence: Supportive of LMWH over UFH in terms of efficacy for intermediate and high risk UA/NSTEMI.

Baird 2002 Baird Sh, M. I. B. M. S. J. T. T. G. W. C. (2002). "Randomized comparison of enoxaparin with unfractionated heparin following fibrinolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. [comment]." European Heart Journal 23(8): 627-32. AIMS: To compare the efficacy and safety of low molecular weight heparin with unfractionated heparin following fibrinolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction. METHODS AND RESULTS: Three-hundred patients receiving fibrinolytic therapy following acute myocardial infarction were randomly assigned to low molecular weight heparin as enoxaparin (40 mg intravenous bolus, then 40 mg subcutaneously every 8 h, n=149) or unfractionated heparin (5000 U intravenous bolus, then 30 000 U. 24 h(-1), adjusted to an activated partial thromboplastin time 2-2.5x normal, n=151) for 4 days in conjunction with routine therapy. Clinical and therapeutic variables were analysed, in addition to use of enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin, to determine independent predictors of the 90-day composite triple end-point (death, non-fatal reinfarction, or readmission with unstable angina). The triple end-point occurred more frequently in patients receiving unfractionated heparin rather than enoxaparin (36% vs. 26%; P=0.04). Logistic regression modeling of baseline and clinical variables identified the only independent risk factors for recurrent events as left ventricular failure, hypertension, and use of unfractionated heparin rather than enoxaparin. There was no difference in major haemorrhage between those receiving enoxaparin (3%) and unfractionated heparin (4%). CONCLUSION: Use of enoxaparin compared with unfractionated heparin in patients receiving fibrinolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction was associated with fewer recurrent cardiac events at 90 days. This benefit was independent of other important clinical and therapeutic factors. Copyright 2002 The European Society of Cardiology.

Prospective, randomised controlled trial. Hypothesis: To determine if there is a benefit of LMWH (enoxaparin) over UFH following fibrinolytic therapy in patients with AMI for reduction of adverse events at 90 days. Primary end point: composite of death, reinfarction, or readmission with unstable angina. N=300, equal groups. Treatment given in prehospital (MD staffed) in 43% of cases or ED setting. There was a 30% relative risk reduction of composite endpoints with LMWH. No increased incidence of clinically significant hemorrhage. Cost comparison also done. LMWH cheaper over 4 day trial.

Level of Evidence: 1 Quality of Evidence: Good design and methodology, moderate sample size and non-blinded. Relevant to prehospital and ED setting. Direction of Evidence: Supportive of LMWH (enoxaparin) over UFH for STEMI post lytics.

Berkowitz 2001 Berkowitz, S. D., S. Stinnett, et al. (2001). "Prospective comparison of hemorrhagic complications after treatment with enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin for unstable angina pectoris or non-ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction." American Journal of Cardiology 88(11): 1230-4. Patients with unstable angina pectoris (UAP) or non-ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction (AMI) are at risk of death or recurrent ischemic events, despite receiving aspirin and unfractionated heparin (UFH). This study investigates the effect of the low molecular weight heparin, enoxaparin, on the incidence of hemorrhage and thrombocytopenia in relation to baseline characteristics and subsequent invasive procedures. Rates of hemorrhage and thrombocytopenia were analyzed for UAP or non- ST-segment elevation AMI in patients included in the prospective, randomized, double- blind Efficacy and Safety of Subcutaneous Enoxaparin in Non-Q-wave Coronary Events 0666d73c299e1a1df1b16f7db322595f.doc Page 16 of 57

REMEMBER TO SAVE THE BLANK WORKSHEET TEMPLATE USING THE FILENAME FORMAT

(ESSENCE) study. Patients received either enoxaparin or UFH, plus aspirin, for 2 to 8 days. The overall rate of major hemorrhage (at 30 days) was comparable between the 2 groups (6.5% for enoxaparin vs. 7.0% for UFH, p = 0.6). The rate of major hemorrhage while on treatment was slightly higher in the enoxaparin group, but this was not significant (1.1% vs 0.7% for UFH, p = 0.204), as was the rate of major hemorrhage within 48 hours of coronary artery bypass grafting performed within 12 hours of treatment. However, the rate of minor hemorrhage was significantly higher in the enoxaparin group, with the majority being injection-site ecchymoses or hematomas (11.9% vs. 7.2% with UFH, p <0.001). Thrombocytopenia (platelet count <100,000 per mm(3)) occurred mainly in association with coronary bypass surgery, with a similar rate in both groups. Thus, enoxaparin is a well-tolerated alternative to UFH in the management of UAP or non-ST- segment elevation AMI. Despite the more effective antithrombotic effect, which results in fewer ischemic events, enoxaparin is not associated with an increase in the rate of major hemorrhagic complications, and is not significantly associated with thrombocytopenia, but is associated with an increase in minor injection site ecchymosis.

Subset of ESSENCE study, looking at hemorrhagic complications after treatment with LMWH (Enoxaparin) or UFH for unstable angina/NonSTEMI. Prospective, randomised, double-blinded controlled study. Concludes that enoxaparin is at least as safe as UFH with regard to major hemorrhage in this setting with no statistical difference between the two groups (although there was a non-statistical trend to increased rate of major hemorrhage while on treatment) With regard to minor hemorrhage there was an increased incidence injection site hematoma associated with LMWH).

Level of Evidence: 2 Quality of Evidence: Excellent design and methods, appropriate to ED/Prehospital setting as addresses safety concerns. Direction of Evidence: Neutral for major hemorrhagic complications, opposing for minor hemorrhagic complications defined as increased rates of injection site hematoma.

Blazing 2004 Blazing, M. A., J. A. de Lemos, et al. (2004). "Safety and efficacy of enoxaparin vs unfractionated heparin in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndromes who receive tirofiban and aspirin: a randomized controlled trial.[see comment] [erratum appears in JAMA. 2004 Sep 8;292(10):1178 Note: Correction of dosage error in text]." 55-64, 2004 Jul 7. CONTEXT: Enoxaparin or the combination of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitor tirofiban with unfractionated heparin independently have shown superior efficacy over unfractionated heparin alone in patients with non-ST-elevation acute coronary syndromes (ACS). It is not clear if combining enoxaparin with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors is as safe or as effective as the current standard combination of unfractionated heparin with glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors. OBJECTIVE: To assess efficacy and safety of the combination of enoxaparin and tirofiban compared with unfractionated heparin and tirofiban in patients with non-ST-elevation ACS. DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS: A prospective, international, open-label, randomized, noninferiority trial of 1 mg/kg of enoxaparin every 12 hours (n = 2026) compared with weight-adjusted intravenous unfractionated heparin (n = 1961) in patients with non-ST-elevation ACS receiving tirofiban and aspirin. Phase A of the A to Z trial was conducted between December 1999 and May 2002. MAIN OUTCOME MEASURES: Death, recurrent myocardial infarction, or refractory ischemia at 7 days in the intent-to-treat population with boundaries set for superiority and noninferiority. Safety based on measures of bleeding using the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) classification system. RESULTS: A total of 169 (8.4%) of 2018 patients randomized to enoxaparin experienced death, myocardial infarction, or refractory ischemia at 7 days compared with 184 (9.4%) of 1952 patients randomized to unfractionated heparin (hazard ratio [HR], 0.88; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.71-1.08). This met the prespecified criterion for noninferiority. All components of the composite primary and secondary end points favored enoxaparin except death, which occurred in only 1% of patients (23 for enoxaparin and 17 for unfractionated heparin). Rates for any TIMI grade bleeding were low (3.0% for enoxaparin and 2.2% for unfractionated heparin; P =.13). Using a worst-case approach that combined 2 independent bleeding evaluations, use of enoxaparin was associated with 1 additional 0666d73c299e1a1df1b16f7db322595f.doc Page 17 of 57

REMEMBER TO SAVE THE BLANK WORKSHEET TEMPLATE USING THE FILENAME FORMAT

TIMI major bleeding episode for each 200 patients treated. CONCLUSIONS: In patients receiving tirofiban and aspirin, enoxaparin is a suitable alternative to unfractionated heparin for treatment of non-ST-elevation ACS. The 12% relative and 1% absolute reductions in the primary end point in favor of enoxaparin met criterion for noninferiority and are consistent with prior trials performed without the use of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors.

A to Z Trial (A phase). Prospective, randomized trial of patients with NSTEMI receiving aspirin and G2b/3a inhibitor (tirofiban) comparing treatment with LMWH (enoxaparin) or UFH. Patients were randomized within 24 hours of symptom onset. Primary end points: combined outcome of death, recurrent myocardial infarction, or refractory ischemia at 7 days (efficacy) and major bleeding (safety).

Level of Evidence: 1 Quality of Evidence: Good design and methods, moderate sample size, non-blinded. Direction of Evidence: Neutral for efficacy and safety of LMWH (enoxaparin) compared to UFH in the setting of GIIb/IIIa inhibitor (tirofiban) use.

Bozovich 2000 Bozovich, G. E., E. P. Gurfinkel, et al. (2000). "Superiority of enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin for unstable angina/non-Q-wave myocardial infarction regardless of activated partial thromboplastin time." American Heart Journal 140(4): 637-642. Background: Whether the clinical superiority of enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin (UFH) depends on a more stable antithrombotic effect or the proportion of patients not reaching the therapeutic level with UFH has not been addressed. Methods: All patients participating in the Thrombolysis In Myocardial Infarction 11B trial who received UFH and had sufficient activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) data (n = 1893) were compared with patients who received enoxaparin (n = 1938). Patients receiving UFH were divided into 3 categories depending on mean aPTT values throughout 48 hours: subtherapeutic, for those in whom the average aPTT fell below 55 seconds; therapeutic, between 55 and 85 seconds; and supratherapeutic, longer than 85 seconds. Events and bleeding rates were determined at 48 hours. Results: A small portion of patients (6.7%) had a subtherapeutic average aPTT value (n = 127). Forty-seven percent of patients (n = 891) fell within the therapeutic range, and 46% were in the supratherapeutic level (n = 875). Event rates were 7.0% in the UFH group versus 5.4% with enoxaparin (P = .039). Events rates were higher in every aPTT strata compared with enoxaparin and statistically significant in the supratherapeutic group (odds ratio 0.65; 95% confidence interval, 0.47- 0.89). Major bleeding rates were 0%, 0.6%, and 0.9% for the subtherapeutic, target, and supratherapeutic strata, respectively, and 0.8% with enoxaparin. Minor hemorrhages occurred in 5.1% of patients receiving enoxaparin versus 3.9%, 2%, and 2.3%, respectively, for the UFH subgroups (P < .001 for all UFH groups vs enoxaparin). Conclusions: Enoxaparin showed a better clinical profile compared with every level of anticoagulation with UFH. Potential mechanisms for enoxaparin superiority are stable antithrombotic activity, lack of rebound thrombosis, and intrinsic superiority.

Post hoc analysis from TIMI 11B. Hypothesis: Enoxaparin superiority is due to a more stable antithrombotic effect rather than the proportion of patients not reaching the therapeutic level with UFH. Problems: Original study not powered to look at UFH subgroups, and only a small proportion of patients were in the subtherapeutic aPTT group. Level of Evidence: 7 Quality of Evidence: Fair design and methods Direction of Evidence: Supportive of LMWH in terms of efficacy, Neutral for safety (major hemorrhage) and opposing for minor hemorrhage (the majority were related to instrumentation or surgery.) Brieger 2002 Brieger, D., V. Solanki, et al. (2002). "Optimal strategy for administering enoxaparin to patients undergoing coronary angiography without angioplasty for acute coronary syndromes." American Journal of Cardiology 89(10): 1167-1170. The optimal strategy for administration of low molecular weight heparin in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) undergoing coronary angiography without percutaneous coronary intervention remains unclear. We studied postangiographic vascular complications in 325 consecutive patients (210 men and 115 women, mean age 0666d73c299e1a1df1b16f7db322595f.doc Page 18 of 57

REMEMBER TO SAVE THE BLANK WORKSHEET TEMPLATE USING THE FILENAME FORMAT

63 years) with ACS undergoing diagnostic coronary angiography via a femoral approach followed by immediate sheath removal. At the time of angiography, 44 patients were on intravenous unfractionated heparin (UFH), 229 on subcutaneous enoxaparin, and 52 on no heparin. Enoxaparin was withheld on the morning of angiography in 181 of 229 patients: the no A.M. dose group. Vascular complications were audited, including hematoma development at angiographic puncture sites; these complications were considered significant if >25 cm2. Major vascular complications requiring transfusion or surgical interventions were infrequent in all groups. Patients receiving enoxaparin on the morning of angiography had a twofold increase in significant hematoma rate compared with the no A.M. dose group (31% vs 16%; p = 0.015). The no A.M. dose group had hematoma rates similar to UFH (20%; p = NS) and no anticoagulation (13.5%; p = NS). No significant increase in ischemic episodes occurred as a result of withholding enoxaparin in the no A.M. dose group. We conclude that omission of enoxaparin on the morning of cardiac catheterization results in vascular complications rates comparable to that of UFH without precipitating rebound ischemia. This is a practical, safe strategy for patients with ACS undergoing coronary angiography, allowing early mobilization for most patients who do not proceed to immediate percutaneous coronary intervention. (C) 2002 by Excerpta Medica, Inc.

Prospective, non-randomised cohort study of patients with ACS undergoing coronary angiography. N=325. No randomisation, no blinding. Hypothesis: Patients treated with LMWH (Enoxaparin) before diagnostic angiography may have increased risk of vascular complications with post- procedure sheath removal compared to those treated with UFH. Outcome measures: Major vascular complications (Ultrasound documented femoral pseudoaneurysm, retroperitoneal hematoma or requirement for surgical intervention or blood transfusion). Secondary measures: Significant wound hematomas. Attempts to address safety concerns post angiography with sheath removal, but does not define an optimal time post LMWH dose at which angiography with sheath removal is safe. Study recommends either withholding am dose of LMWH, or delaying sheath removal. Level of Evidence: 3 Quality of Evidence: Fair Direction of Evidence: Opposing for safety of LMWH given on the morning of angiography when there is immediate sheath removal. Neutral for safety of LMWH compared to UFH when am dose is omitted prior to angiography with immediate sheath removal. Brosa 2002 Brosa, M., C. Rubio-Terres, et al. (2002). "Cost-effectiveness analysis of enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin in the secondary prevention of acute coronary syndrome." Pharmacoeconomics 20(14): 979-987. Background: The Efficacy and Safety of Subcutaneous Enoxaparin in Non-Q- Wave Coronary Events (ESSENCE) and Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction (TIMI) 11B studies revealed that enoxaparin reduced the incidence of death, myocardial reinfarction and recurrent angina in patients with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) compared with unfractionated heparin (UFH). Objective: To perform a pharmacoeconomic analysis to evaluate the cost effectiveness of treatment with enoxaparin compared with UFH in Spanish patients with ACS. Design and setting: Retrospective cost-effectiveness analysis using data and costs from Spanish sources, conducted from the perspective of the National Health System. Patients, interventions and outcomes measures: The study was based on the results of the ESSENCE and TIMI 11B clinical trials, which included more than 7000 patients with ACS treated with enoxaparin or UFH. The main variables studied were the success rate, expressed as patients with no complications (reinfarction, unstable angina or death), and the decrease in the utilisation of healthcare resources (revascularisation procedures and hospitalisation). Results: The base-case results of the analysis showed superior efficacy and lower total treatment and follow-up costs with enoxaparin compared with UFH. The total savings in direct health costs per patient with enoxaparin ranged between 448 and 659 euros (time horizons of 1 month and 1 year, respectively) [2001 values]. The sensitivity analysis results confirmed the advantage of enoxaparin in all cases, except in one scenario: when simultaneously using all the minimum values of the confidence interval for absolute risk reduction (ARR) in the utilisation of health resources. Conclusions: This study suggests that enoxaparin is a more effective and less expensive treatment option than UFH in secondary prevention of patients with ACS in Spain, confirming the results obtained in other pharmacoeconomic 0666d73c299e1a1df1b16f7db322595f.doc Page 19 of 57

REMEMBER TO SAVE THE BLANK WORKSHEET TEMPLATE USING THE FILENAME FORMAT

analyses performed in the UK, USA, France and Canada.

Retrospective extrapolation using the ESSENCE and TIMI 11B studies to conduct a pharmacoeconomic analysis. Possibly biased by fact that population of study was not same population of economic analysis. Level of Evidence: 7. Quality of Evidence: Fair design and methods. Direction of Evidence: Supportive of cost efficiency of LMWH (enoxaparin) being superior (cheaper) in comparison to UFH in Spain. Campos 2002 Victoria Campos, J., U. Juarez Herrera, et al. (2002). "Decreased total bleeding events with reduced doses of Enoxaparin versus unfractionated heparin in high risk unstable angina. [Spanish]." Archivos de Cardiologia de Mexico 72(3): 209-219. In this prospective, randomized and controlled study, we compare complications in 2 groups of patients: group 1, enoxaparin 0.8 mg/kg, subcutaneous every 12 hours during 5 days, and group 2, intravenous unfractionated heparin during 5 days, by infusion treated to activate partial tromboplastin time 1.5-2 the upper limit of normal. Blood samples were obtained at 4, 12, 24 hours and at day 5 of treatment, to measure anti-Xa levels, and also, evaluated end points at 30 days, between groups. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed with clinical and angiographic variables between groups, with p < 0.05. Results: 203 consecutive patients, average age of 60.5 +/- 11.2 years, and 80% men, were included. There were no differences in clinical and angiographic characteristics. All patients with enoxaparin had therapeutic levels of anti-Xa, of 0.5 to 0.67 U/mL. There was increasing risk of total bleeding in group 2 (18.7%) than in group 1 (5.6%), with RR = 1.72 (95% CI 1.29,2.29), p = .003. Also, there was 33.3% of MACE in group 2, and only 17.8% in group 1, with RR = 1.88 (CI 95% 1.29, 2.29), p = .011. Conclusions: 1) Low doses of enoxaparine achieve therapeutic levels, since the first 4 hours of treatment. 2) A significant reduction of total bleeding occurred with the low doses of enoxaparin, with the same efficacy to reduce MACE during follow- up.

Translation from Spanish into English obtained. Prospective randomised controlled trial in Mexican patients with UA/NSTEMI, randomized within 48 hours of qualifying symptom onset. Compares a lower dose of LMWH (enoxaparin 0.8mg/kg/dose) to UFH. N=203. Primary outcome measures: Therapeutic serum levels of anti-Xa and major complications that included death, AMI, emergency coronary revascularization, refractory angina, and total hemorrhages. Level of Evidence: 2 Quality of Evidence: Good Direction of Evidence: Supportive of lower dose LMWH (enoxaparin) in terms of safety and efficacy.

Clark 2000 Clark, S. C., N. Vitale, et al. (2000). "Effect of low molecular weight heparin (Fragmin) on bleeding after cardiac surgery." Annals of Thoracic Surgery 69(3): 762-764. Background. Fragmin (Dalteparin, Pharmacia Ltd, Milton Keynes, UK), a low molecular weight heparin, is now recommended in the treatment of unstable angina. Due to the greater bioavailability and longer half-life of Fragmin compared with conventional heparin we postulated that this may influence postoperative bleeding after cardiac surgery for unstable angina. Methods. We investigated the influence of the agent on postoperative bleeding after cardiac surgery. Patients undergoing first-time coronary artery bypass grafting were prospectively studied in four groups: group A (n = 100) were elective patients; group B (n=60) had unstable angina and received conventional heparin intravenously until operation; group C (n=115) received Fragmin with the last dose administered more than 12 hours before surgery; and group D (n=115) received Fragmin within 12 hours of operation. Results. Patients in group D had significantly greater blood loss (p < 0.001) and increased blood transfusion than groups A, B, and C (p = 0.047). Patients receiving Fragmin more than 12 hours before surgery (group C) had similar rates of blood loss and transfusion to group B (p > 0.05) but greater than in group A (p = 0.021). There were no differences in reopening rate. Conclusions. The risks of bleeding and transfusion must be weighed against the risks of acute ischemic events if Fragmin is stopped more than 12 hours before operation. (C) 2000 by The Society of Thoracic 0666d73c299e1a1df1b16f7db322595f.doc Page 20 of 57

REMEMBER TO SAVE THE BLANK WORKSHEET TEMPLATE USING THE FILENAME FORMAT

Surgeons.