Rescue From; Rescue For by Rev Allister Lane

14th July 2013

Luke 10:25-37 Colossians 1:1-14

Have you ever been to a film preview before it’s publically released? Well, I don’t like to brag... but this week I was invited to a film preview.

It was a special screening for clergy-only, which sounds a little naff, ...but it was at Peter Jackson’s Park Road Post in Miramar!

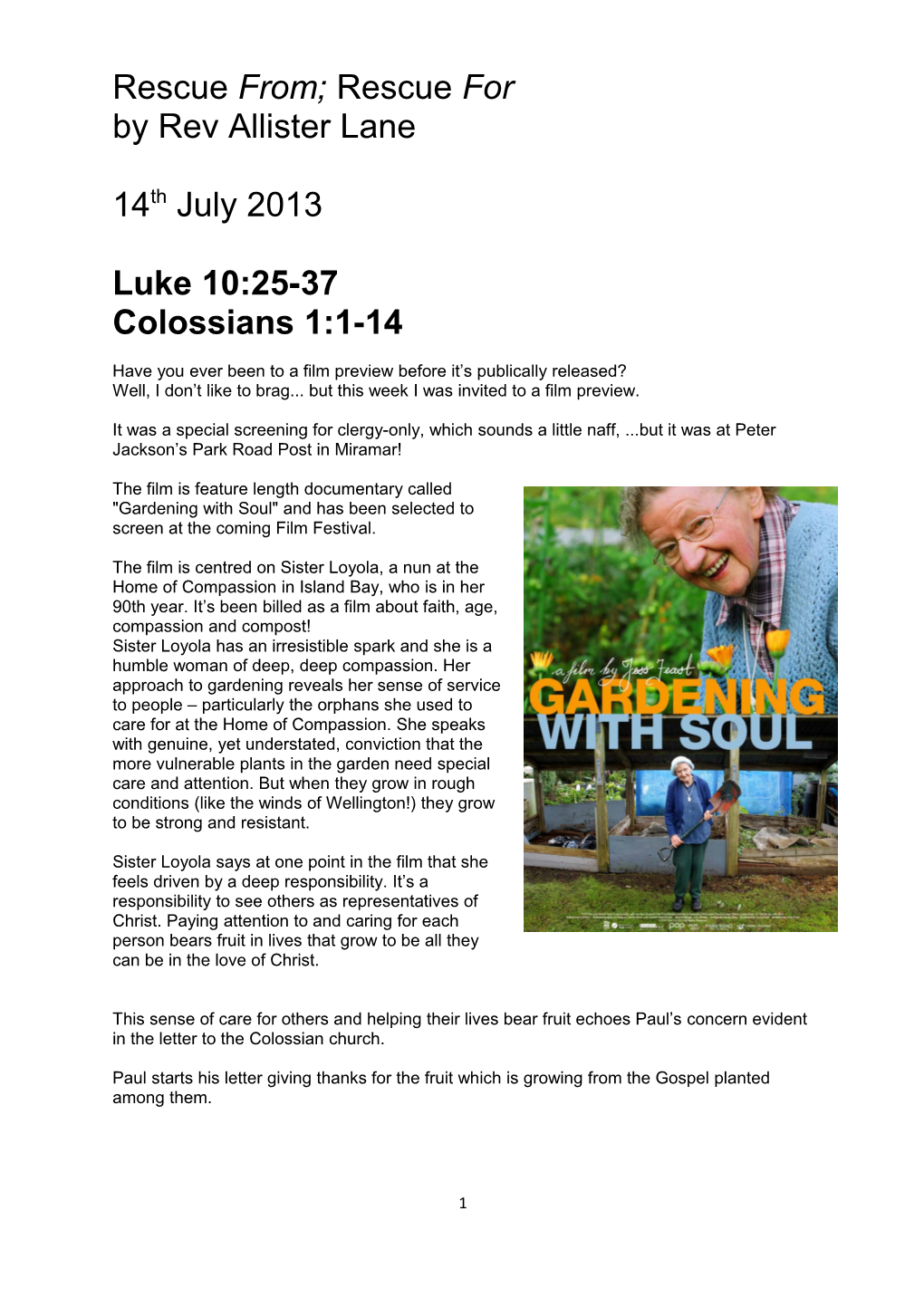

The film is feature length documentary called "Gardening with Soul" and has been selected to screen at the coming Film Festival.

The film is centred on Sister Loyola, a nun at the Home of Compassion in Island Bay, who is in her 90th year. It’s been billed as a film about faith, age, compassion and compost! Sister Loyola has an irresistible spark and she is a humble woman of deep, deep compassion. Her approach to gardening reveals her sense of service to people – particularly the orphans she used to care for at the Home of Compassion. She speaks with genuine, yet understated, conviction that the more vulnerable plants in the garden need special care and attention. But when they grow in rough conditions (like the winds of Wellington!) they grow to be strong and resistant.

Sister Loyola says at one point in the film that she feels driven by a deep responsibility. It’s a responsibility to see others as representatives of Christ. Paying attention to and caring for each person bears fruit in lives that grow to be all they can be in the love of Christ.

This sense of care for others and helping their lives bear fruit echoes Paul’s concern evident in the letter to the Colossian church.

Paul starts his letter giving thanks for the fruit which is growing from the Gospel planted among them.

1 “Just as it is bearing fruit and growing in the whole world, so it has been bearing fruit among yourselves from the day you heard it and truly comprehended the grace of God.” (v6)

Paul sees the Gospel is filled with potential and power – it much more so than simply a body of knowledge to be conveyed and comprehended. The Gospel is planted and emerges in the midst of the community, with life, colour, fragrance, and fruit for all. Paul sees the Gospel not just as a new religious experience, but as nothing less than a new creation.

And in his letter to them, Paul acknowledges the tell-tale signs of the new creation in the church community: “we have heard of your faith in Christ Jesus and of the love that you have for all the saints, because of the hope laid up for you in heaven.” (v4-5)

These signs of authentic Christian community: ‘faith, hope and love’, are signs Paul uses in other letters (e.g. 1 Corinthians 13:13).

Paul is thankful for the healthy sings of genuine faith growing in this church, and writes to them out of a commitment to continue to nurture them in faith.

Over three Sundays we will look at Paul’s letter to the Colossians and reflect on the character of the faith he hopes will grow among them. He encourages them, sharing his theological insights, which (through our own prayer and reflection) offer us nurture and growth for our faith also.

Common to the three passages from this letter we’ll hear over the coming weeks is the central importance of Jesus Christ.

Specifically, Jesus Christ is unique as revealer and redeemer. He is not one among many; he has not partially revealed God, or imperfectly secured redemption.

Paul wants to prevent a domestication of Jesus to serve other (lesser) agendas. At the same time Paul wants to give certainty to the content and character of the church’s faith. Not certainty to our own abilities/competencies/sense of what’s right – but certainty uniquely in the person of Jesus Christ.

Another film I want to mention this morning is Argo, which won the Oscar last year for Best Picture.

Set in 1980s Iran, Argo focuses on the fallout from the revolution, in which the US-installed dictator, who had been in power for most of the preceding three decades, was forced out before fleeing to America. Following the coup, the new Iranian government demanded he be extradited back to face trial for his crimes. When the US refused, its embassy in Tehran was stormed. Over 60 American citizens and diplomats were held hostage and only six managed to escape, taking shelter in the

2 nearby Canadian embassy and remaining hidden from the Iranian authorities with no clear way out from the country. Into the story steps Tony Mendez (played by Ben Affleck), a renowned ‘exfiltration’ expert charged with bringing the escaped diplomats home safely without compromising the ongoing hostage situation. What makes the story so remarkable is the idea they are forced to settle on (what’s called the “best bad idea that we have”): faking a location scouting trip for a Hollywood science fiction movie, and smuggling the refugees out as a makeshift film crew.

It’s a story of a rescue – and a rescue is always such a powerful premise for a gripping story. One of the taglines for the film is: “How the CIA and Hollywood pulled off the most audacious rescue in History”.1 The most audacious rescue in history...?

The story of Argo certainly has similarities with the Gospel – this idea about someone selflessly stepping into a situation to rescue the lost and needy is one familiar to Christians.

As powerful as the rescue story told in Argo is, and as similar as the rescue story is to that of the Gospel, Paul would insist that the rescue story of Jesus Christ is unique.

The rescue story of Jesus is a cosmic rescue, that only God is able to complete. “He has rescued us from the power of darkness and transferred us into the kingdom of his beloved Son, in whom we have redemption, the forgiveness of sins.” (vv13-14)

As my sermon title suggests, Jesus completes a ‘rescue from’ and a ‘rescue for’. A rescue from the power of darkness. A rescue for life lived in the Kingdom.

We are redeemed by Jesus from sin to live authentically in God’s reality, defined by faith, hope, and love. Freed from sin our lives are an exciting discovery of what faith, hope, and love means for our families, our community, our world. We are rescued for this adventure of life in Jesus Christ.

We live like this, not because we need to be rescued, and certainly not in order to be rescued. We live like this because we have been rescued.

When Paul describes the rescue by Jesus as a rescue out of one reality and into another one, he builds on the tradition of Israel’s Exodus from Egypt. The rescue from slavery under the power of the Pharaoh, for worshipping God at Mount Sinai and the Promised Land. Jesus’ rescue is the new Exodus.

Jesus has rescued us from the power of darkness and sin. So what has Jesus rescued us for...?

As I said a moment ago the living we are enabled to live is not about some sort of ‘self- recue’ attempt, but a response to the freedom we have been given, having been rescued. This is the wonderful liberation of God’s grace in Jesus Christ.

1 Another of the taglines is “The movie was fake; the mission was real”.

3 We have been rescued for freedom in Christ. Freedom to love.

Perhaps we don’t feel rescued. Maybe we feel we’re in a pretty dark place at the moment.

The Gospel news doesn’t offer us complete freedom from any difficult and painful experiences. However these experiences are not what define us and our future.

We join in the rescue from and rescue for – a reality that is a Kingdom “now but not yet”. That’s the adventure of trusting God in all things, seeking reconciliation, seeking forgiveness for ourselves and others, loving our enemies. Of course there is a costliness to this reality, but the rewards are fruit that are eternal, as our faith grows in Jesus Christ.

In the story of the Good Samaritan Jesus opens up our imaginations to what living in the Kingdom is about. Jesus tells the story in response to a question “What must I do to inherit eternal life?” (v25) And it would seem to diminish the meaning of Jesus’ story to a narrow ethical instruction to offer first aid to victims of random robberies.

The story is a celebrated one precisely because it throws off the narrowness of the question, opening up beautiful possibilities, as the usual assumptions about ‘who does what’ are turned on their heads; and at the same time reinforcing human motivations of compassion, to which we all aspire.2

Which brings us back to Sister Loyola.

She understands herself living freely in the love of Christ. Living with compassion, paying attention to and caring for others, choosing to get down and dirty – just as Jesus chose to do the costly thing.

How do we understand our freedom in the love of Christ? What motivates us in the discovery, the adventure, of faith? What compels us to take risks to join in God’s rescue and to do the costly thing?

I conclude with Paul’s encouraging words... May [we] be filled with the knowledge of God’s will in all spiritual wisdom and understanding, so that we may lead lives worthy of the Lord, fully pleasing to him, as we bear fruit in every good work and as we grow in the knowledge of God. AMEN.

2 Is Jesus establishing a specific ethical obligation by telling the story of the Good Samaritan? It seems one of the messages (to those who identify with the Priest and Levite characters) is to be FREE of, at least some, obligations. Or, if you like, replacing all ‘lesser’ obligations with one unique ‘obligation’ – to love as we have been loved. And even then it’s not really an obligation, unless we’d describe a human experience like falling in love as imposing an obligation to do things for another person. We do things freely for the person precisely because we love them.

4