Grade 4 Answer Key READING

Please mark your answer for each multiple-choice question by filling in the circle completely for the correct answer. Mark only one answer for each question. If you do not know the answer, make your best guess.

Earl Weber lived on a small farm during the Great Depression, a time when many people in the United States did not have jobs or much money. Read how the Weber family lived through these hard times. Answer the questions that follow.

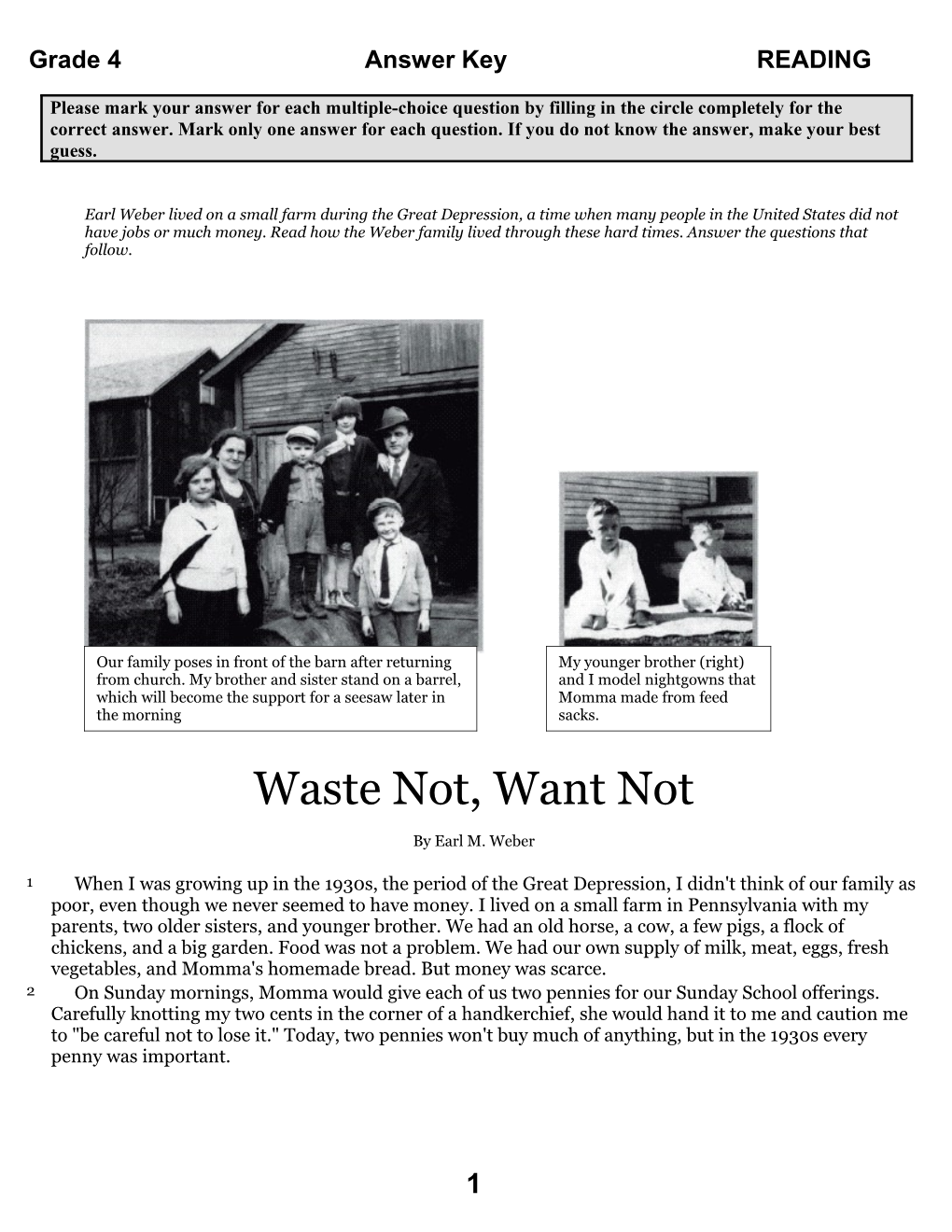

Our family poses in front of the barn after returning My younger brother (right) from church. My brother and sister stand on a barrel, and I model nightgowns that which will become the support for a seesaw later in Momma made from feed the morning sacks. Waste Not, Want Not

By Earl M. Weber

1 When I was growing up in the 1930s, the period of the Great Depression, I didn't think of our family as poor, even though we never seemed to have money. I lived on a small farm in Pennsylvania with my parents, two older sisters, and younger brother. We had an old horse, a cow, a few pigs, a flock of chickens, and a big garden. Food was not a problem. We had our own supply of milk, meat, eggs, fresh vegetables, and Momma's homemade bread. But money was scarce. 2 On Sunday mornings, Momma would give each of us two pennies for our Sunday School offerings. Carefully knotting my two cents in the corner of a handkerchief, she would hand it to me and caution me to "be careful not to lose it." Today, two pennies won't buy much of anything, but in the 1930s every penny was important.

1

The four of us dressed up for Sunday School on a spring morning. We had to wear garters, which were a nuisance, to hold up our long stockings.

3 As a boy of nine, I only had a vague idea of what it meant to live during hard times. The weekly newspaper would carry pictures of people standing in line for bread, and the evening newscast on our tabletop Crosley radio would tell about the huge number of jobless people and their hardships. But these reports referred to people in the cities, and we lived in the country. We never went to bed hungry, and we didn’t stand in line for bread. 4 Although my father was fortunate to have a job at the feed mill, his salary of eighteen dollars a week was barely enough to pay the farm mortgage and the electric bill, and to buy necessities like the flour and yeast Momma needed to bake her bread. 5 Momma earned a few dollars baking pies and bread, which she sold at the local market. Twenty cents for a pie and ten cents for a loaf of bread! Sometimes I helped at the market, and if we had a good day, Momma would give me a nickel for an ice- cream cone. 6 Momma used the market money to buy clothing for the family. With four children and two adults to clothe, she seldom bought anything new. One day when I walked to the mailbox at the end of our lane, I was excited to see a package from Sears, Roebuck and Company. That usually meant new clothing for one of us. As it turned out, I was the lucky one this time, with a brand-new pair of brown tweed knee-length knickers. Although we always went to school looking neat and clean, most of our clothing was patched, darned*, or mended. So to me, a new pair of knickers was very special. 7 Christmas was special, too, because then we got new socks, and for a little while we wouldn’t have to 10 wearAlmost socks nothing darned in in our the house toes andwas heels.thrown away. Store parcels were generally tied with string. We saved 8 this Momma string bymade winding some itof on our a ball.clothing, One usingof my ajobs treadle was (foot-powered)to wash and flatten sewing used machine. tin cans. To We make nailed these nightgowns,pieces of tin she over used holes the in muslin the barn sacks roof that to stop our chickenthe leaks feed and came over in.holes I wore in the a nightgowncorncrib to with stop "PRATT'Sthe mice CHICKENand rats from FEED" eating printed the corn. in big black letters on the front. (It wasn’t until years later when my high- 11 schoolA wooden class crate went was on anconsidered overnight a tripreal that prize. I got We my would first take store-bought it apart for pajamas.) future projects, Some companies being careful actually not putto splittheir the feed boards. in sacks We made even of straightened colorfully patterned the bent nailscalico. and Momma stored likedthem this in a material tin can. for making aprons 12 andAlthough dresses. we tend to think of recycling as something fairly new, in the 1930s it was part of everyday life. 9 "Waste When not, a piece want of not" clothing was awas familiar worn out,and oftenit wasn’t repeated thrown phrase away. during First, all those the Depressionbuttons were years. removed, sorted by size and color, and put in cans or glass jars. Then the clothing was examined, and the best parts were cut into strips and saved for making rugs.

PLEASE GO ON TO THE NEXT PAGE

2 Yesterday and Today In the 1930s, a chocolate bar cost five cents. A single-dip ice-cream cone was also five cents. If that sounds good, consider that children living in the country, if they were lucky enough to have a job, earned only ten cents an hour for farm labor. Kids today pay around a dollar for an ice-cream cone and about the same for a chocolate bar. But some can earn five dollars an hour baby-sitting or mowing lawns.

Copyright © 2001 by Highlights for Children, Inc., Columbus, Ohio

1. According to the article, how did the author’s mother help the family? Ο She washed and flattened tins to repair holes in the roof. Ο She stood in line for bread for the family’s food every day. Ο She baked pies and bread to sell and made the family’s clothes. Ο She had a job at the feed mill and grew vegetables..

2. Which word BEST describes the author when he noticed a package in the mailbox? Ο proud Ο bored Ο thrilled Ο concerned

3. According to the article, how did the author’s mother use feed sacks? Ο She mended socks with them. Ο She repaired leaks in the roof with them. Ο She patched holes in the corncrib with them. Ο She made nightgowns, dresses, and aprons with them.

4. Why didn’t the author feel poor living during the Great Depression? Ο His family was wealthy. Ο He and his family got everything they needed from the bread lines. Ο He and his family had what they needed. Ο He and his family had plenty of money.

PLEASE GO ON TO THE NEXT PAGE

3 READING OPEN-RESPONSE QUESTIONS

Read all parts of each open-response question before you begin. Write your answers to the open-response questions in the space provided in this test booklet.

Write your answer to question 5 in the space provided on the next page.

5. Although we tend to think of recycling as something fairly new, it was a part of everyday life in the 1930s.

A. Describe 3 ways the author’s family benefited from reusing items. B. Compare recycling in the 1930s to recycling in modern times.

Do not write on this page. Please write your answer to this open-response question on the next page.

PLEASE GO ON TO THE NEXT PAGE

4 READING 5 ..

PLEASE GO ON TO THE NEXT PAGE

5 Have you ever wondered why your shadow seems to come and go? Read to find out how one child feels about his shadow. Answer the questions that follow.

I have a little shadow that goes in and out with me, And what can be the use of him is more than I can see. He is very, very like me from the heels up to the head; And I see him jump before me, when I jump into my bed.

5 The funniest thing about him is the way he likes to grow— Not at all like proper children, which is always very slow; For he sometimes shoots up taller like an india-rubber ball, And sometimes gets so little that there's none of him at all.

He hasn't got a notion of how children ought to play, 10 And can only make a fool of me in every sort of way. He stays so close beside me, he's a coward you can see; I'd think shame to stick to nursie as that shadow sticks to me! One morning very early, before the sun was up, I rose and found the shining dew on every buttercup; 15 But my lazy little shadow, like an arrant sleepy-head, Had stayed at home behind me and was fast asleep in bed.

—Robert Louis Stevenson PLEASE GO ON TO THE NEXT PAGE

6 Read line 2 from the poem in the box below.

And what can be the use of him is more than I can see.

5. What does this line mean? Ο The speaker does not know how to talk to his shadow. Ο The shadow does not know how to jump for the speaker. Ο The shadow does not understand how to behave like a child. Ο The speaker does not understand the purpose of his shadow.

6. Based on the poem, what about the shadow is MOST unlike a child? Ο the way he hides Ο the way he grows Ο the way he jumps Ο the way he sleeps

7. Why does the speaker call his shadow a coward in line 11 of the poem? Ο His shadow stays asleep in bed. Ο His shadow stays with him. Ο His shadow imagines how he feels. Ο His shadow shows him how to play.

8. Which of the following lines from the poem is an example of a simile? Ο I have a little shadow that goes in and out with me, Ο For he sometimes shoots up taller like an india-rubber ball, Ο And can only make a fool of me in every sort of way. Ο Had stayed at home behind me and was fast asleep in bed.

PLEASE GO ON TO THE NEXT PAGE

7 Read this selection about a girl who forgot something important on the school bus and is faced with a big problem. Answer the questions that follow.

The Skirt by Gary Soto

After stepping off the bus, Miata Ramirez turned around and gasped, "Ay!" The school bus lurched, coughed a puff of stinky exhaust, and made a wide turn at the corner. The driver strained as he worked the steering wheel like the horns of a bull. Miata yelled for the driver to stop. She started running after the bus. Her hair whipped against her shoulders. A large book bag tugged at her arm with each running step, and bead earrings jingled as they banged against her neck. "My skirt!" she cried loudly. "Stop!" She had forgotten her folklórico skirt. It was still on the bus.

"Please stop!" Miata yelled as she ran after the bus. Her legs kicked high and her lungs burned from exhaustion. She needed that skirt. On Sunday after church she was going to dance folklórico. Her troupe had practiced for three months. If she was the only girl without a costume, her parents would wear sunglasses out of embarrassment. Miata didn't want that. The skirt had belonged to her mother when she was a child in Hermosillo, Mexico. What is Mom going to think? Miata asked herself. Her mother was always scolding Miata for losing things. She lost combs, sweaters, books, lunch money, and homework. One time she even lost her shoes at school. She had left them on the baseball field where she had raced against two boys. When she returned to get them, the shoes were gone. Worse, she had taken her skirt to school to show off. She wanted her friends to see it. The skirt was old, but a rainbow of shiny ribbons still made it pretty. She put it on during lunchtime and danced for some of her friends. Even a teacher stopped to watch. What am I going to do now? Miata asked herself. She slowed to a walk. Her hair had come undone. She felt hot and sticky. She could hear the bus stopping around the corner. Miata thought of running through a neighbor's yard. But that would only get her in trouble. "Oh, man," Miata said under her breath. She felt like throwing herself on the ground and crying. But she knew that would only make things worse. Her mother would ask, "Why do you get so dirty all the time?"

What am I going to do now? she asked herself. She prayed that Ana [her friend] would find the skirt on the bus. She's got to see it, Miata thought. It's right there. Just look, Ana. As Miata rounded the corner onto her block she saw her brother, Little Joe, and his friend Alex. They were walking with cans smashed onto the heels of their shoes, laughing and pushing each other. Their mouths were fat with gum. Little Joe waved a dirty hand at Miata. Miata waved back and tried to smile.

If Ana doesn't pick up the skirt, she thought, I'll have to dance in a regular skirt. It was Friday, late afternoon. It looked like a long weekend of worry.

From THE SKIRT by Gary Soto. Illustrated by Eric Velasquez, copyright © 1992 by Gary Soto. Illustrations © 1992 by Eric Velasquez. Used by permission of Random House Children's Books, a division of Random House, Inc.

PLEASE GO ON TO THE NEXT PAGE 8

8. Why did Miata take the skirt to school? A. She was proud of it. B. She was in a class play. C. It was her day for "Show and Tell." D. Ana wanted to borrow it. Read this selection about a girl who forgot something important on the school bus and is faced with a big problem. Answer the questions that follow.

The Skirt by Gary Soto

After stepping off the bus, Miata Ramirez turned around and gasped, "Ay!" The school bus lurched, coughed a puff of stinky exhaust, and made a wide turn at the corner. The driver strained as he worked the steering wheel like the horns of a bull. Miata yelled for the driver to stop. She started running after the bus. Her hair whipped against her shoulders. A large book bag tugged at her arm with each running step, and bead earrings jingled as they banged against her neck. "My skirt!" she cried loudly. "Stop!" She had forgotten her folklórico skirt. It was still on the bus.

"Please stop!" Miata yelled as she ran after the bus. Her legs kicked high and her lungs burned from exhaustion. She needed that skirt. On Sunday after church she was going to dance folklórico. Her troupe had practiced for three months. If she was the only girl without a costume, her parents would wear sunglasses out of embarrassment. Miata didn't want that. The skirt had belonged to her mother when she was a child in Hermosillo, Mexico. What is Mom going to think? Miata asked herself. Her mother was always scolding Miata for losing things. She lost combs, sweaters, books, lunch money, and homework. One time she even lost her shoes at school. She had left them on the baseball field where she had raced against two boys. When she returned to get them, the shoes were gone. Worse, she had taken her skirt to school to show off. She wanted her friends to see it. The skirt was old, but a rainbow of shiny ribbons still made it pretty. She put it on during lunchtime and danced for some of her friends. Even a teacher stopped to watch. What am I going to do now? Miata asked herself. She slowed to a walk. Her hair had come undone. She felt hot and sticky. She could hear the bus stopping around the corner. Miata thought of running through a neighbor's yard. But that would only get her in trouble. "Oh, man," Miata said under her breath. She felt like throwing herself on the ground and crying. But she knew that would only make things worse. Her mother would ask, "Why do you get so dirty all the time?"

What am I going to do now? she asked herself. She prayed that Ana [her friend] would find the skirt on the bus. She's got to see it, Miata thought. It's right there. Just look, Ana. As Miata rounded the corner onto her block she saw her brother, Little Joe, and his friend Alex. They were walking with cans smashed onto the heels of their shoes, laughing and pushing each other. Their mouths were fat with gum. Little Joe waved a dirty hand at Miata. Miata waved back and tried to smile.

If Ana doesn't pick up the skirt, she thought, I'll have to dance in a regular skirt. It was Friday, late afternoon. It looked like a long weekend of worry.

From THE SKIRT by Gary Soto. Illustrated by Eric Velasquez, copyright © 1992 by Gary Soto. Illustrations © 1992 by Eric Velasquez. Used by permission of Random House Children's Books, a division of Random House, Inc.

PLEASE GO ON TO THE NEXT PAGE

8. Why9. didWhy Miata did take Miata the take skirt the to skirtschool? to school? A. SheΟ wasShe proud was proud of it. of it. B. SheΟ wasShe in was a class in a play. class play. C. It was her day for "Show and Tell." Ο It was her day for "Show and Tell." D. Ana wanted to borrow it. Ο Ana wanted to borrow it.

10. From this selection, we can tell that Miata is Ο tall Ο forgetful Ο smart Ο funny

11. The word folklórico comes from Ο Classical music Ο New England dialect Ο a language other than English Ο standard American English

STOP!

9