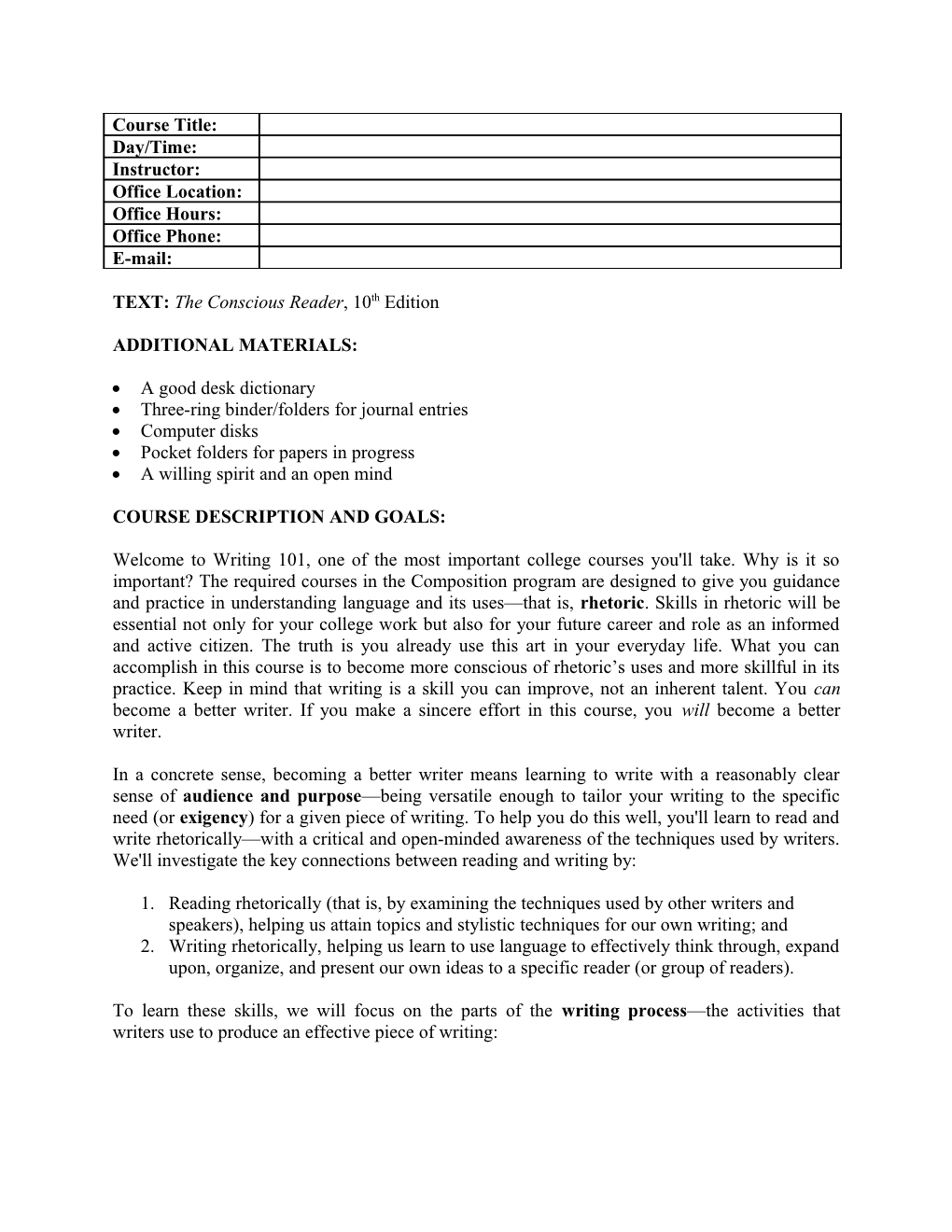

Course Title: Day/Time: Instructor: Office Location: Office Hours: Office Phone: E-mail:

TEXT: The Conscious Reader, 10th Edition

ADDITIONAL MATERIALS:

A good desk dictionary Three-ring binder/folders for journal entries Computer disks Pocket folders for papers in progress A willing spirit and an open mind

COURSE DESCRIPTION AND GOALS:

Welcome to Writing 101, one of the most important college courses you'll take. Why is it so important? The required courses in the Composition program are designed to give you guidance and practice in understanding language and its uses—that is, rhetoric. Skills in rhetoric will be essential not only for your college work but also for your future career and role as an informed and active citizen. The truth is you already use this art in your everyday life. What you can accomplish in this course is to become more conscious of rhetoric’s uses and more skillful in its practice. Keep in mind that writing is a skill you can improve, not an inherent talent. You can become a better writer. If you make a sincere effort in this course, you will become a better writer.

In a concrete sense, becoming a better writer means learning to write with a reasonably clear sense of audience and purpose—being versatile enough to tailor your writing to the specific need (or exigency) for a given piece of writing. To help you do this well, you'll learn to read and write rhetorically—with a critical and open-minded awareness of the techniques used by writers. We'll investigate the key connections between reading and writing by:

1. Reading rhetorically (that is, by examining the techniques used by other writers and speakers), helping us attain topics and stylistic techniques for our own writing; and 2. Writing rhetorically, helping us learn to use language to effectively think through, expand upon, organize, and present our own ideas to a specific reader (or group of readers).

To learn these skills, we will focus on the parts of the writing process—the activities that writers use to produce an effective piece of writing: Invention (getting ideas), planning (deciding what to do with those ideas), Collecting (gathering facts/information on your topic), Arrangement (deciding the best order for presentation of your ideas), Drafting (early attempts to put your ideas into clear, focused writing), Revising (analyzing drafts and formulating a more effective presentation), and Editing/polishing (improving grammar, spelling, punctuation).

It is important, however, to remember that the writing process isn't as simple as just following a set of steps. If you use the activities described above thoughtfully, by the end of the course you should be able to write more clearly, more convincingly, and more confidently. To accomplish these goals, however, you must commit yourself to the sincere effort that effective writing requires, avoiding short cuts (in writing, there really are no good short cuts).

Our Central Topic Base: Rhetoric, Conscious Reading, and the Examined Life:

Good writing involves not only clarity and correctness, but also informed thinking—that which is developed not only by individual reflection but also through stimulating reading and conversation. So that we can have such conversations in this class, we will be focusing our reading on the wide variety of human issues that call for our critical and thoughtful responses.

Not only is critical thinking and response crucial to our personal growth, but it is also part of your becoming an active member of our culture. It is important for all of us to reflect upon the values around us so that we are informed enough to form thoughtful and reasonable decisions about our own lives and our society. You can do so, as the title of our reader suggests, by reading consciously—actively and with the desire to respond to the ideas you find. Doing so is a large part of what Socrates called "the examined life"—one that is conscious of the many important issues we face as individuals and members of society.

As you read about the many issues raised in The Conscious Reader, it is important for you to become more observant and thoughtful readers. That means not only noticing what writers write about, but also how they write about it. Observing the various uses of rhetoric will make you more thoughtful writers as well.

One more thing: Good writing always comes from examined thoughts. You're in college, I assume, to both learn more about the world in which you live and to acquire the education you need to find a satisfying and secure job. One way to process the ideas you hear is through the filter of the set of interests that led you to your field of study. If you are a prospective engineer, you might consider environmental issues from that standpoint; if you are a prospective teacher, you might consider how diversity in the classroom affects you now or how television will affect your students; if you're a budding scientist, you might consider whether gender is a biological or cultural standard. Remember, write from your interests and your strengths, and when you are lacking information and answers, be willing to do the research required to find them. The Companion Website accompanying The Conscious Reader can be a great starting point.

READING AND CLASSWORK: SRATEGIES FOR SUCCESS: The goal of our discussions will be to compare various approaches to issues in our text rhetorically. Reading assignments will be made on a weekly basis, and will serve as the basis for discussion of the issues raised therein as well as the rhetorical techniques used to discuss those issues. My strong suggestion is that you get into the habit of reading a bit each day—30 minutes may suffice. You’ll also need to make time for writing and revising regularly. Don't try to complete your assignments in a single session. Good writing must be done over time, and those who do well in this class are almost always those who heed this advice. Also get in the habit of writing informally in your journal regularly, keeping track of your reactions to the readings we do on a daily basis. If you are consistent in these tasks, completing the formal writing assignments will be much easier since you will have lots of material in your head and in your notes upon which you can draw.

Methods of Instruction:

In this class, you can expect to:

Write every day in a variety of formats responding to things we read, doing prewriting activities for essays, and drafting or revising formal papers Spend class time in writing workshops practicing various rhetorical techniques Analyze the techniques and strategies of others’ writing Examine your own writing's strengths and challenges in individual conferences with me Learn new stylistic options in a number of ways: not only through lectures, but more often through your own careful analysis of published writings, your own writing, and writing done by your peers Work in small groups to discuss your own and classmates’ writing

College Writing Center:

Free help with your writing—what's not to like? You are encouraged to make use of the individual tutoring available in the Writing Center. Experience shows that this service is beneficial for writers at all levels; in fact, the best writers know that seeking outside advice is crucial. This help will be most effective if you make use of it early in the semester, and then again at any stage of the writing process: for discussing ideas, for thinking through possible sources or methods of organization for your papers, for advice on revision, and/or for help with specific challenges you face as a writer. To make these sessions as effective as possible, go to the center prepared with your syllabus, assignment sheet, and work in progress. Remember, tutors are there to provide advice and expertise, but responsibility for the quality of your writing remains your own.

Academic Standards and Format:

Students enrolled in this class are expected to use correct and effective English in their speech and in their writing. All formal papers submitted must conform to standards of correctness set by the Modern Language Association (MLA), though prewriting activities depend more upon inventive thought than polished presentation. Grades on written work will be based on expression as well as content (though it is really not possible to completely separate the two). Grades will be adversely affected by errors in grammar, punctuation, spelling, and/or organization. But as noted above, correctness is not all you need to be a good writer.

Assignments:

All formal assignments must be completed adequately for you to pass the course. Assignments should be typed. Seriously consider using a word processor, which will make the mechanics of revision—rearranging, adding, deleting—much easier. Computer labs are available on our campus. The hours are posted outside each lab.

Academic Dishonesty:

Plagiarism is the unacknowledged use of information or words from someone else's writing. This can happen intentionally, when you use someone else's words as your own; or unintentionally, when you fail to properly cite your sources. If you have questions about how to cite a source, please ask an authority and/or consult the writing handbook. Remember that if you plagiarize, you are subject to the penalties listed in the Student Handbook, including failing the course being referred to the Dean for possible disciplinary action. Bottom line: don't do it. If you're uncertain, please speak to me rather than risk your academic career.

WRITING REQUIREMENTS:

I. JOURNAL OR “WRITER’S NOTEBOOK

To help you become more "conscious" readers, of both the readings in the text and the world around you, I'll ask you to think critically about many issues that affect and inform our culture. Your writer's journal will be a place for you keep track of various ideas and values discussed in our readings, and to connect those ideas with those you hear directly or indirectly in the wider world—in other classes, in discussions with friends and family, on TV, on the radio, over the Internet, and in films. As a result of your journal-keeping you will be able to better understand how the issues raised in The Conscious Reader relate to the culture in which we live.

At midterm and at the end of the semester I'll collect the whole journal and assess your work. My assessment will be based upon not only the amount of writing and reflection you've done based upon assigned readings, but also upon the supplementary materials you've added and the depth of critical thought you bring to each entry. You’ll be using the journal both in and out of class; so keep it nearby at all times.

In addition to informal journal-writing and exercises, we'll be completing a variety of specific writing tasks—all of which will draw upon the thoughts and writings you collect in the journal.

II. UNDERSTANDING RHETORIC A. Rhetorical Analysis (2–3 pages): This paper will help you to recognize the rhetorical modes of persuasion in other people's writing and in media presentations. B. Brief arguments (3 letters: 1 page each): Writing these concise letters will give you the opportunity to respond to things you hear or read in the media and give you practice using various modes of persuasion that will later be useful in more extended arguments.

III. WORKING WITH OTHER PEOPLE'S WORDS

A. Article summary (2–3 pages): This paper will give you practice in reading carefully to understanding the crux of another writer's argument, then summarizing it fairly and briefly. This skill will be useful for multisource or research papers. B. Dialogic Response (4–5 pages): This paper will give you practice bringing together two or more related arguments and analyzing the value in each. You may also, through your own critical thought, expand upon those arguments and/or expose potential counterarguments. The goal is for you to successfully "converse" with other writers on topics that interest you.

IV. FORMING YOUR OWN ARGUMENT

A. Sophisticated Proposal (2–3 pages): This paper will help you to envision and plan your own argument, considering (1) the information you will need; (2) the available strategies to make your case effectively for a specific audience; (3) formation of a solid thesis; and (4) how to collect and organize the information. B. Multisource Position Paper (6–9 pages): This paper will allow you to bring together all the techniques and strategies of the writing process with which we will work during the semester.

V. THE PORTFOLIO

Generally speaking, a portfolio is something that represents you and your best work. Artists use portfolios to show a representative sample of their work; businesspeople use portfolios to present their achievements; teachers use portfolios to showcase their teaching style and materials. As this class proceeds, I'll ask you to assemble a portfolio of your work from this class. It will include: A. A cover memo to me, describing its contents and your progress over the semester; the cover memo should, more than anything else, map how your semester's work developed into a specific set of interests and your development as a writer. B. At least 5 entries from your writer's journal, organized as you think best for showing your semester's thought processes. C. One of the letters from assignment #2—the one you think works best, in its REVISED form. D. The research paper, with a cover memo describing how the project developed and changed since your original proposal, its topic/purpose/audience, where you might publish this piece, and what further revisions might be necessary before it is sent out to a real audience. You should also discuss what you like best about this piece, how it helps define your goals as a writer, and how it displays your writing skills from the semester. E. Whatever other materials or information you'd like to include to help show who you are as a writer.

GRADING:

Simply stated, your grade will be determined by the quality of your writing. Your grade for any given piece of writing will be the answer to a question I ask myself: What are the chances that this piece of writing will succeed in its given rhetorical situation? That is, I will assess how well you develop a specific topic for a specific purpose with a specific audience in mind.

So . . .

A piece of writing very likely to succeed will receive an A.

A piece of writing which has a better-than-average chance of succeeding will receive a B.

A piece of writing that has an average chance of succeeding or minimally makes its case will receive a C.

And writing that doesn't succeed will receive a D or an F. But let's try not to be negative.

Since the writing you produce will be intended for intelligent, professional, and/or academic audiences, its success will also depend upon your use of standard written English. For what are the chances of a piece of writing succeeding if it is marred by spelling and grammatical errors? Would it likely to be published or accepted by other instructors? Would such a resume get you a job? On the other hand, a polished, edited piece of writing is necessary, but not sufficient. Consider this scenario: You write an essay with no errors, but it does not make a strong case. Perhaps it does not provide sufficient evidence. Perhaps its tone is more likely to anger than convince your audience. Even though there are no "errors," such an essay is not particularly likely to succeed. Correct? Further, I'll weight the various assignments’ grades based on their degree of difficulty. See chart below.

Grading Weights:

Rhetorical analysis: worth up to 50 points A = 50 B = 40

C = 30

D = 10 F = 0

Three Brief Arguments (Letters): worth up to 30 points each; 90 points total

A = 30 B = 20 C = 10 D = 5

F = 0

Article Summary/Response: worth up to 160 points A = 160 B = 120 C = 80 D = 40 F = 0

Sophisticated Proposal: worth up to 150 points

A = 150 B = 110 C = 80 D = 40 F = 0 Multisource paper: worth up to 250 points A = 250 B = 190 C = 140 D = 70 F = 0 Portfolio, including Notebook: worth up to 300 points A= 300 B =220 C = 150 D = 70 F = 0

Final Grades:

A = 890-1000

B = 680 –889 C = 460-679 D = 300-459 F = 0-299

TENTATIVE SCHEDULE:

The following schedule outlines our day-to-day topics and formal writing assignments for the upcoming semester. Journal assignments will be made on a week-by-basis. We'll keep as close as we can to this schedule, but it may become necessary to make a few additions or deletions as we go, so be adaptable! It's important to keep up with both your reading and writing assignments.

Week Topics Reading Due Writing Due 1 Course Intro Art and Composition: Journal: Analyses of Active Reading, View images in the first section artworks and artist's motives Conscious Reading of The Conscious Reader Using our Texts Art and Composition: Responding to "Texts," Visual and Written 2 What is Rhetorical Analysis? Emotions: Journal: Emotional Types of Persuasion: Annie Dillard responses Emotions, Logic, and Greg Graffin Character Anne Sexton 3 Rhetorical Analysis Logic Journal: Logical and (continued) Bruno Bettelheim character-based responses Reynolds Price Paper 1: Rhetorical analysis: Character DRAFT DUE for peer Alice Walker review James Baldwin 4 Inventing Arguments: Using Narrative: Paper 1: Rhetorical the Modes Aryeh Stollman Analysis, POLISHED Sura 12: Joseph PAPER DUE

Description: Journal: Responses to Edwidge Danticat readings Theodore Roethke 5 Inventing Arguments Analysis: Journal: Analyzing modes (continued) Roland Barthes of invention in readings Ursula Melendi Leo Braudy

Comparison/Contrast: D. H. Lawrence Jared Diamond 6 Inventing Arguments Definition: Paper 2: Three Brief (continued) Andrew Sullivan Arguments: DRAFT DUE Thomas Merton for peer review Writing Arguments Julian Johnson David Dubal 7 Principles and Goals of Thomas Jefferson Paper 2: Three Brief Summary: Hearing Others' The Seneca Falls Convention Arguments: POLISHED Arguments Martin Luther King, Jr. PAPER DUE Dorothy Day Journal: Brief summaries of readings 8 Writing a Formal Summary Essay of your choice Paper 3: Article Summary: DRAFT DUE for peer review 9 Reading as Dialogue: Dialogue on the Environment Paper 3: Article Summary: Hearing Divergent Voices Henry David Thoreau POLISHED PAPER DUE E. O. Wilson Alan Tennant Journal: Brief responses to readings 10 Creating a Dialogue Among Essays of your choice for Journal: Responses to Written Texts dialogic response chosen articles

Paper 4: Dialogic Response: DRAFT DUE 11 Proposals: Purpose, Proposals: Journal: Initial Topic Audience, and Conscious Kevin Finneran Proposals Reading Declaration of the Rights of Man Mary Wollstonecraft Eric Schlosser 12 Writing a Credible Proposal Articles for your multi-source Paper 5: Sophisticated Topic paper Proposal Due 13 Learning About a Topic: Note-taking Practice: Journal: Notes for Careful Reading, Note- Gary Wills multisource paper taking, Response Randall Kennedy 14 Arranging and Planning a Articles for your multisource Multisource Paper paper 15 Strategies for Drafting and Organization Strategies: Multisource "Position" Revision; Collaborative Susan Sontag Paper: DRAFT DUE for Revision Howard Gardner Peer Review 16 Course Wrap-Up Paper 6: Multisource Position Paper: POLISHED PAPER DUE