Soda Lake by Richard Alston

Study Notes This pack was compiled by Rambert Learning and Participation and has not been rewritten for the new specifications for exams in AS and A level Dance from 2017 onwards, although it is hoped that these notes will be a starting point for further work. Some of the material was adapted or reproduced form earlier resource packs.

We like to thank Richard Alston, choreographer and former Rambert artistic director, for his invaluable help in compiling these notes.

Practical workshops with Rambert are available in schools or at Rambert’s studios. To book, call 020 8630 0615 or email [email protected].

This material is available for use by students and teachers of UK educational establishments, free of charge. This includes downloading and copying of material. All other rights reserved. For full details see www.rambert.org.uk/join-in/schools-colleges/educational-use-of-this- website/.

Rambert Sofa Lake Study Notes p2 Contents

About Soda Lake page 4

Features of the production page 5

Description of the dance page 8

Movement material and analysis page 10

Practical teaching ideas page 13

Rambert Sofa Lake Study Notes p3 About Soda Lake

Choreography: Richard Alston Design: Nigel Hall Soda Lake (1968) Lighting: Sid Ellen

Soda Lake is a solo for a male or female dancer.

The first performance took place as part of a workshop season at Riverside Studios, London on 15 April 1981. It was first performed by Ballet Rambert at the Royal Northern College of Music, Manchester on 4 February 1986.

Soda Lake was originally conceived for a BBC programme. When the project failed to come to fruition Richard Alston decided to make the piece for a performance space instead, and it was first presented at a Rambert workshop evening at Riverside Studios, London, for Ballet Rambert dancer Michael Clark.

Danced by Clark, Soda Lake was recorded in a shortened version and presented in a South Bank Show which gave an overview of Richard Alston's work. The piece was performed live only at a small number of venues by Clark but it was revived for the repertoire of Ballet Rambert in 1986, having not been seen on stage for more than four years. Four Rambert dancers have followed Clark as performers in the work: Mark Baldwin; Ben Craft; Cathrine Price and Amanda Britton.

Rambert Sofa Lake Study Notes p4 Features of the production

Costume

The dancer wears a black leotard (with short sleeves in the first production and later, when performed by Rambert, sleeveless (male) or with long sleeves (female)) with matching, tightly-fitting, slightly flared trousers. The dancer is barefoot.

Set

The set comprises a sculpture entitled Soda Lake, created by Nigel Hall in 1968. The sculpture is a response to the physical geometry of a part of the North American Landscape, Soda Lake in the Mojave Desert. Nigel Hall has said that ‘the scale of Soda Lake was vast…the place had sparse features, so sparse that they served only as minimal markers - an occasional rock, plant or telegraph pole in an otherwise empty landscape.’

The sculpture itself comprises two separate pieces that are hung from the ceiling (or flies in the theatre). One piece is a plain large free-hanging rod hung perpendicularly from the ceiling. Its tip does not quite reach the floor. Hanging at it its left (when viewed from the front of the stage) is a piece which comprises an oval hoop, aligned parallel with the ceiling, from which a plain narrow rod descends at a steep diagonal, its tip touching the floor.

Alston whose initial training was in art, was impressed by Hall's sculpture which he had seen at the Warwick Gallery, London. The sculpture became the set for the dance but also generated images in Alston's choreography, both to do with the metal pieces themselves in the space and with the Nevada desert of the title.

At the first performance of Soda Lake the original sculpture was used but later a replica was made for performances by Ballet Rambert.

Accompaniment

Soda Lake is performed in silence, although it was originally intended that Nigel Osborne (composer of the music for Wildlife and Zansa by Alston) create music for the piece. However Osbourne felt the music would detract from the dance and therefore rejected the offer, saying that the dance would be more effective in silence. The only audible sounds are those of the dancer's breath and of the dancer's feet on the stage surface.

Lighting

In the stage performance of Soda Lake the dance commences in silhouette. As the dancer begins to move the lights are raised until white light washes the stage. The light remains intense until the dancer undertakes the last movement, at which point the lights are lowered once more to silhouette. In the video performance (1990) of the

Rambert Sofa Lake Study Notes p5 dance the lighting is bright and remains unchanged throughout because of the needs of the camera for recording.

Starting point (or stimulus) for the dance

Soda Lake is a choreographic response to Nigel Hall's sculpture. It is an abstract work, as is the sculpture. The piece deals with two aspects of Hall's sculpture, its shape and the way it affects the space in which it stands, and the original starting point for the sculpture, Soda Lake in the Mojave Desert.

In relation to the first aspect, the piece makes choreographic references to the shape and line of the sculpture, as well as embellishing the space in which it stands. In relation to the second, in certain sections of the work the dynamic qualities of the movement material allude to the movement qualities of small desert creatures, where rapid flurries of movement appear to conjure up a sense of never ending expanses of land unmarked by obvious landmarks. This is achieved through the use of expansive peripheral gestures and a careful use of focus.

Characteristics of Style

The movement vocabulary of Soda Lake shows an influence of Cunningham technique and of release-based work fused with movement inspired by Clark's own physique. The Cunningham influence is seen in the varied and fluent use of the torso and the rhythmic complexity of the faster sections of the dance. Release technique is apparent in the use of stillness that has an ongoing sensation.

Rambert Sofa Lake Study Notes p6 Soda Lake contains several central poses and motifs that are repeated and/or varied as the piece progresses. The main ones are:

. A position which sees the dancer lying on his side on the floor, his head resting on his arm (See Photograph 2). This recurs in different variations throughout the piece.

. A distorted arabesque, arms raised above the head, chest open, upper back arched, free foot flexed (See Photograph 3 page 6). This is known as the `big swan' and is repeated several times.

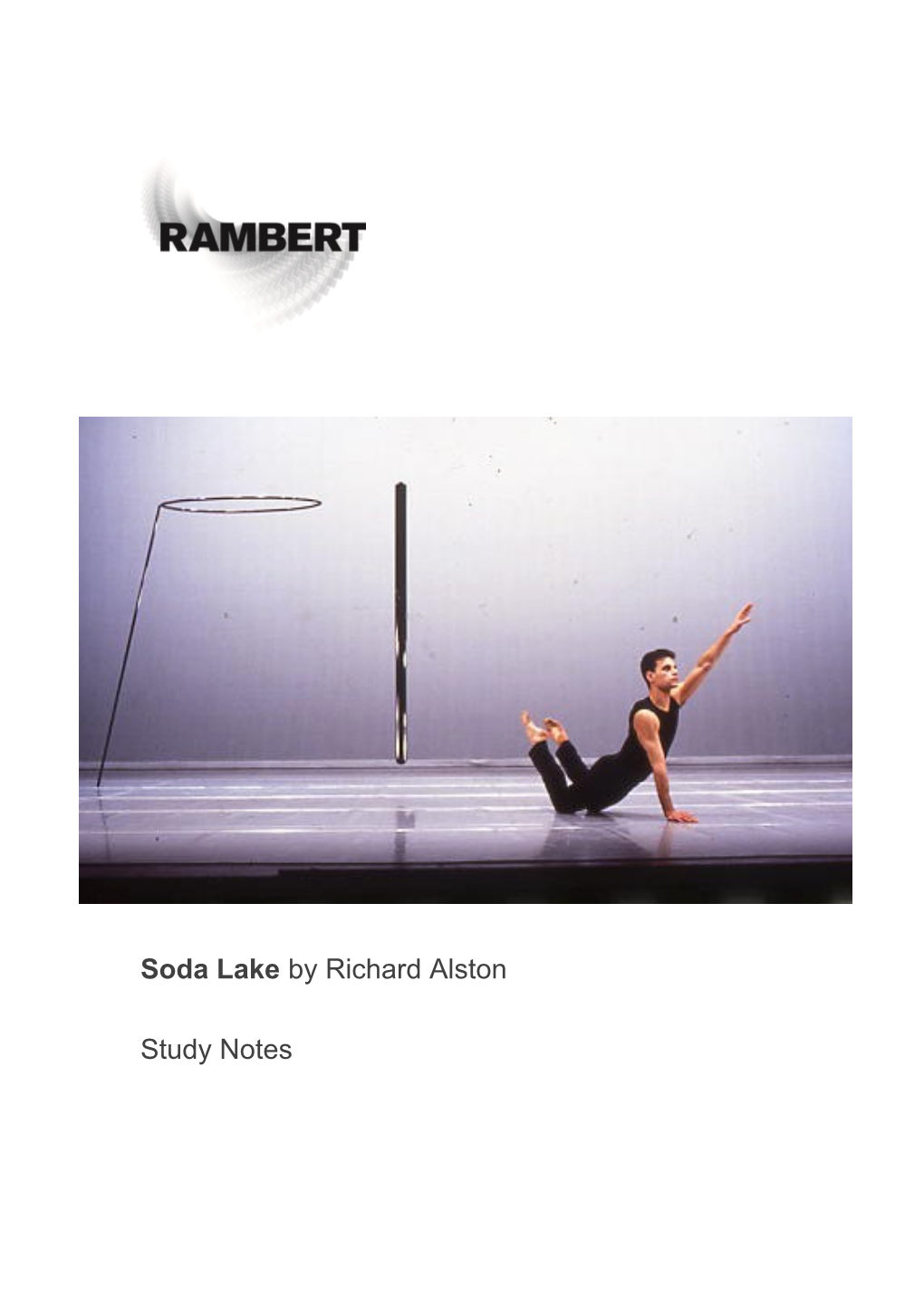

. A position in which the dancer balances on his knees and one hand, his body from the knees to the top of his other hand stretched out before him at an angle of approximately 45 from the floor (See front cover). This position has been described as the ‘sentinel’.

. A side fall, which is repeated in different variations during the piece.

. A turning sissone (a jump in which the dancer takes off from two feet and lands on one foot).

Structure

The piece contains four distinctive sections that highlight changes in action, dynamic and use of space. Changes can also be seen in the relationship between the dancer and the sculpture and distinct held positions that act as structural guidelines throughout the work.

The first section (prelude) establishes the importance of the space and the effect the sculpture has upon it. The second section relates directly to the form of the sculpture. The third section relates both to the starting point of the sculpture and its formal properties linking them with the dancer’s use of space and shape. The fourth and final section serves as an epilogue as the dancer slowly and deliberately repeats a series of positions that have previously been shown in the dance.

Rambert Sofa Lake Study Notes p7 Description of the dance

First section (prelude)

The dancer begins lying on his side facing the back of the stage. He rolls over very slowly towards the front, pauses briefly in the same lying position, rolls again and assumes a curled up sitting position, the body over, and arms wrapped around the knees.

He then pauses, rises to his feet, performs a very short sequence of movements, frequently initiated by swings of the arms and/or legs, sinks back to the floor and reassumes the lying position this time facing stage left. The movements here are best described as ‘flurries of movement’. The complete sequence of slow movements, is repeated again, but ends in a tipped attitude facing the sculpture.

Second section

The dancer moves into travel (a simple run, centre of gravity placed low) and pauses under the sculpture. Here he assumes a position in which the arms echo the shape of the hoop which hangs above his head. He travels again, following a circular pathway and returns to the sculpture, traces the shape of the hoop with his arm, and allows the motion to take him to the floor. Here he once again echoes the shape of the hoop, this time with his body (on his side, legs and arms extended, back arched).

The dancer rolls, rises, moves to the sculpture and echoing the verticality of the hanging rod, performs a deep plié in parallel, drawing his hand through the tiny space underneath the rod at the culmination of the plié. He falls, rises and executes a rapid series of movements, pauses in a position which echoes the line of the diagonal rod descending from the hoop. He then performs another series of rapid movements and comes to stillness in a different position which echoes another aspect of the sculpture’s form. The dancer ends this section lying in his initial starting position facing stage left, adding another visual element to the sculpture.

The use of the floor space is expansive. The travelling material both circles the space and cuts a diagonal path through it. The dancer also pauses in different points in the space, frequently near to the edge, although always relating directly to the sculpture (which is placed close to the upstage right corner).

Rambert Sofa Lake Study Notes p8 This section sees the appearance of several of the central motifs in the piece, the side fall, the hinge with arm gestures, the ‘big swan’ (See photograph 3 above), the ‘sentinel’ and several of their variations and repetitions. One series of movements, which includes a diagonal travel ending in a lunge, followed by the hinge accompanied by the arm gesture and culminating in the ‘big swan’ makes an important appearance later in the piece.

Third section

This section is characterised by a series of rapid sequences of movement, which gives it a very active feel, punctuated by pauses, stillness and occasional slow movements. This is in direct contrast to the previous section in which the slow movement material was punctuated by fast sequences. The section ends with the dancer assuming the ‘sentinel’ position, facing directly out to the audience. Several of the motifs which made their appearance in the first and second section re-appear here, in particular the turning sissone and the side falls.

The use of floor space is less expansive in this section. Much of the movement takes place centre stage, the dancer tracing tight circular floor patterns while executing the material. The positions assumed in the pauses, however, seem to project the

Rambert Sofa Lake Study Notes p9 dancer’s energy and consciousness beyond the confines of the space with the dancer focusing out to the back of the auditorium.

Fourth section

The ‘sentinel’ is repeated immediately, the weight balanced on the other hand, then the dancer rolls slowly to rest in the lying position facing stage right. He rises into a low arabesque, arms raised high, then he repeats the movement material that commences with a long diagonal travel described in section two. However, in this section it is performed more slowly.

After reaching the swan position the dancer sinks to his knees into the ‘sentinel’ reaching out towards the sculpture, softens and rolls to return to his starting position, lying on his side facing the back of the stage. The dance ends as it began.

Movement material and analysis

‘Alston turned to Nigel Hall's Soda Lake sculpture...to create one of his most memorable pieces...remarkable for its sense of calm, a silent dance in which stillness alternated with flurries of activity. The dance explored areas around and along the horizontal and vertical paths suggested by the two elements of the sculpture, reaching up and tracing its oval loop above, reflecting the frisson of the near contact of the pole to the floor, often referring back to the pole as if it were back to base.’ Stephanie Jordan and Howard Friend: Artists Design for Dance/Arnolfini Catalogue

‘The place from which the sculpture takes its title is a dry lake in the Mojave desert. The scale was vast and the place had sparse features, so sparse that they served only as minimal markers...The subject matter of Soda Lake is space, and its components determine how the space is channelled, trapped or disclosed.’ Nigel Hall in conversation with Bryan Robertson Warwick Arts Trust Gallery catalogue 1980.

The movement material contains typical Alston choreographic traits including an interest in balance and off-balance, the influence of body weight and gravity, and contrasts in speed and associated rhythmic complexity.

Much of the movement material of Soda Lake is concerned with going from on- balance to off-balance and allowing body-weight to initiate motion. Falls of various types, some giving in to the floor at their conclusion, others being caught and held mid-fall, appear throughout Soda Lake.

Rambert Sofa Lake Study Notes p10 Alston also focuses on bodyweight whether the dancer is on the floor or air bound. The floor sequence that opens the dance introduces rolls and stretches which luxuriate into and along the floor. Similarly the elevation sequences which follow in a later section of the dance, whilst taking the dancer’s weight upwards and away from the floor, have a natural sense of weight

There is a focus on contrasts in speed throughout Soda Lake, where the dancer goes from stillness to rapid movement within a fraction of a second. Stillness and calmness punctuate the dance, however pauses are not finite and depend on the individual dancer performing the role. In stillness, a sense of breathing movement is maintained and even at speed the dancer retains a sense of calm and relaxation rather than frantic hurry.

Although performed in silence, Soda Lake has a clear logical rhythm of its own. When movement is slow in pace, the rhythms are the natural ones that emerge from the body and have an organic quality as the movement reflects the breathing and pauses of the dancer. However, during the faster sections, the rhythm gains in momentum and complexity, at times demonstrating irregular rhythmic meter.

Interpretation of Soda Lake inevitably focuses on the relationship between the dancer and sculpture; namely the formal relationship between the spatial qualities of dance and design and also the association of both the sculpture and dance with the inspiration for the sculpture, the dry lake in the Mojave Desert. The relationship between the dancer and sculpture is variable according to the dancer’s position on the stage. When the dancer stands and moves underneath the sculpture he becomes part of it, his torso silhouetted against the white back drop like the outline of the poles. Here his movements are slower, more deliberate, gradual transitions between one momentary image and the next. When moving around the sculpture, the links are the connecting lines between dancer and sculpture and the relationship between the dancer’s and the sculpture’s form.

Alston investigates in depth, the shape and paths of the sculpture in the movements he creates for the dancer. He echoes the bold black vertical pole with a recurrent movement in which the dancer stands tall and appears to be hanging like the pole. Similarly the dancer traces the shape of the loop at the top of the thinner angled pole, notably at the beginning of the section two when the dancer stands directly beneath the loop and follows its path with a stretched raised arm.

Rambert Sofa Lake Study Notes p11 Like the sparse Mojave Desert punctuated only by the minimal markers of rocks, plants and telegraph poles, Alston punctuates his Soda Lake with markers, namely the central poses and motifs listed earlier. There are intervals between these markers, both in terms of time and space, and their repetition is divided by other movement phrases and there is space between the dancer and the sculpture. The structure of section three of the dance also highlights the idea of punctuation of expanses of space through its ‘flurry and pause’ composition in which time is marked by sharp changes in dynamics.

Alston furthers the physical, geographical desert allusions by adding only one figure to Hall’s work, leaving the stage, apart from the sculpture and a single dancer, otherwise empty. The silence of the dance intensifies the dancer’s solitude in the space and the frantic whirlpools of energy followed by stillness seem to indicate the individual’s isolation and despair.

The significance of the work is derived through reference to the inspiration for Hall’s sculpture and knowledge of the environment to which it relates. This knowledge then influences the dancer's activities on stage.

Rambert Sofa Lake Study Notes p12 Practical teaching ideas

The quality of movement used in Soda Lake is very specific and provides it with its strength and meanings. In order to conduct a workshop using material from Soda Lake it is important to get students into the correct frame of mind, which one could describe as contemplative.

In order to do this it is wise to give a class which emphasises slow unhurried movements, skeletal balance rather than the use of muscular strength to control movement, and which employs the use of internalised movement imagery. (For example using imagery employed in ‘new dance’ techniques such as Release, in which dancers imagine the placement of the shoulders above the pelvic bone, the line of the vertebrae in the spinal column, the circulation of the breath through the limbs and body, etc.).

Practical Tasks

1. Ask students to perform a controlled fall to the floor over 2 counts. Repeat the fall on 10 counts, rise on 10, then repeat on 8,6,4,3,2,1. There should be no pause between rising and falling nor between each repetition of the fall. The result should be a seamless flow of movement. Repeat the exercise using a different fall for each series. (Before embarking on this exercise ensure that the students know the principle of the fall, particularly with regard to preventing injury of elbow and knee joints, etc.).

Now ask students to create a sequence that commences with a slow fall, includes

Rambert Sofa Lake Study Notes p13 a rest position on the floor, rises into a delicately balanced position such as a tipped attitude, or extended arabesque. Ask them to perform it with a light quality, and to emphasise the pauses and the suspension in the final position.

Ask each student to learn the sequences of others in order to get a different sense of the movement and qualities. Individual sequences can then be performed by groups of 7 or 8 at the same time, perhaps repeated in different places in the room and facing in a different direction. Ask students watching the sequences to note the different timings of the rise and fall of the group etc.

2. Place an object with an interesting shape in the middle of the room, or ask a student to go the centre of the room and assume a shape. Each student in turn approaches the object/person and assumes a complementary shape. This should be done spontaneously as an immediate response to the object and not be a contrive shape planned before the approach to the object. This may be a difficult exercise for younger students.

Ask students to choose an interesting shape or combination of shapes in the room and to look at them in relation to the space around them. They could choose objects that they place in the room in relation to a line or shape chosen from the perimeters. (Students could also bring in free-standing sculptures from their art studies). Ask them then to create a sequence which relates directly to this starting point (and which complements the shape in some way). It should include both axial and travelling sequences.

3. Ask students to visualise a tract of flat land in which the horizons are barely visible. Images of deserts or plains can be used. Ask students to create a travelling sequence punctuated by pauses, which give a sense of spaciousness. Encourage them not to use tricky step sequences but to concentrate on floor patterns and covering the ground.

4. Ask students to create 3 sequences comprising a series of rapid movements which emphasises radical changes in direction, and which employ a continuous flow of energy. Then ask them to create a short series of movements, one or two at most, which are very slow and emphasise the way in which positions are reached by looking at air patterns and moments of stillness in the movement. These should take place on the spot.

Ask students to combine the two series in any way they please to create a study of contrasting qualities. Try to encourage use of the qualities employed in Alston’s Soda Lake.

It may be worth collaborating with the art department on a project in which visual arts objects are used as the starting point for a dance piece. The stimulus for the whole project could be agreed by both departments, the students working first on the sculpture and then on the dance piece.

Rambert Sofa Lake Study Notes p14 Rambert 99 Upper Ground London SE1 9PP [email protected] Tel: 020 8630 0600

Images from Soda Lake by Catherine Ashmore Male dancer: Mark Baldwin; female dancer: Amanada Britton.

Rambert is supported by Arts Council of England and is a registered charity no. 326926.

Rambert Sofa Lake Study Notes p15