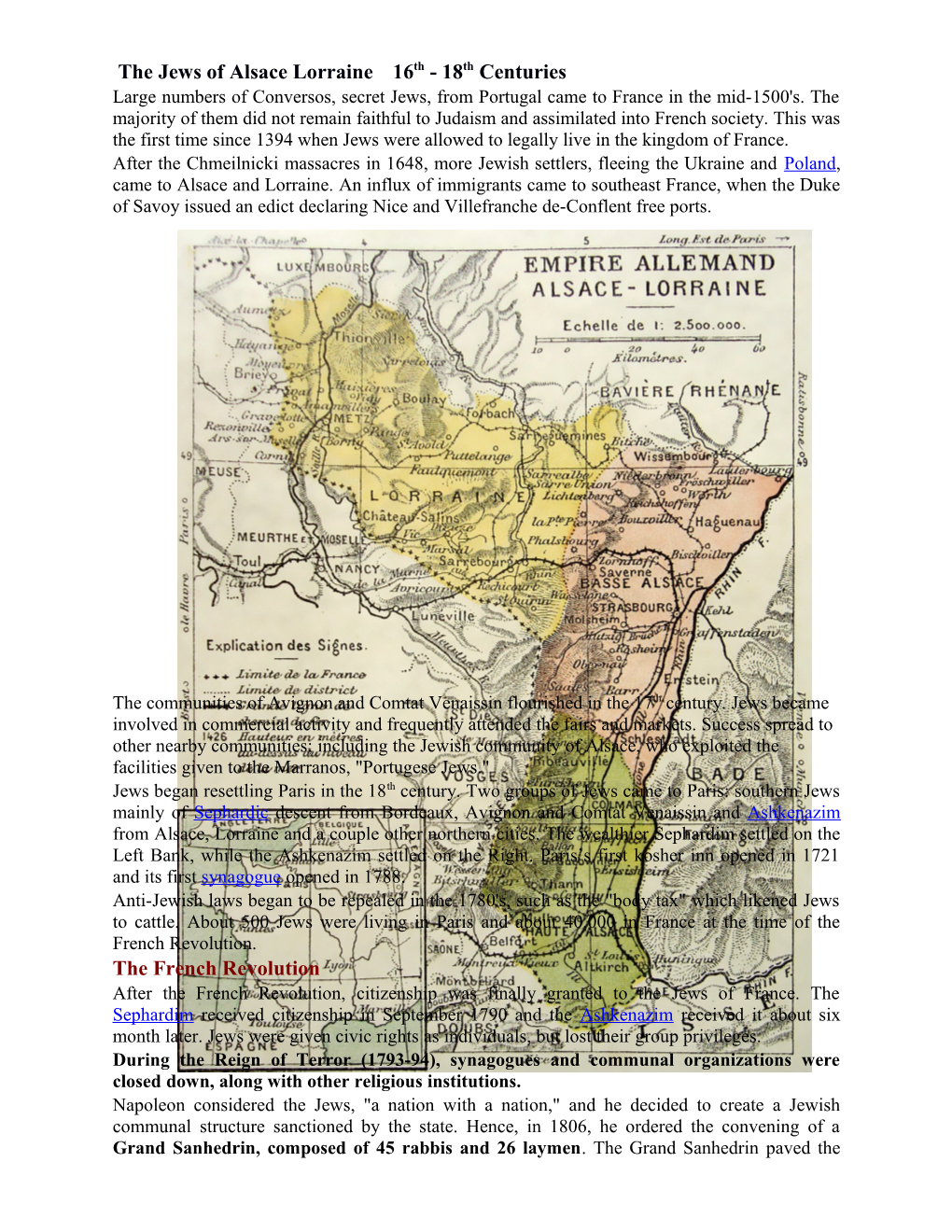

The Jews of Alsace Lorraine 16th - 18th Centuries Large numbers of Conversos, secret Jews, from Portugal came to France in the mid-1500's. The majority of them did not remain faithful to Judaism and assimilated into French society. This was the first time since 1394 when Jews were allowed to legally live in the kingdom of France. After the Chmeilnicki massacres in 1648, more Jewish settlers, fleeing the Ukraine and Poland, came to Alsace and Lorraine. An influx of immigrants came to southeast France, when the Duke of Savoy issued an edict declaring Nice and Villefranche de-Conflent free ports.

The communities of Avignon and Comtat Venaissin flourished in the 17th century. Jews became involved in commercial activity and frequently attended the fairs and markets. Success spread to other nearby communities; including the Jewish community of Alsace, who exploited the facilities given to the Marranos, "Portugese Jews." Jews began resettling Paris in the 18th century. Two groups of Jews came to Paris: southern Jews mainly of Sephardic descent from Bordeaux, Avignon and Comtat Venaissin and Ashkenazim from Alsace, Lorraine and a couple other northern cities. The wealthier Sephardim settled on the Left Bank, while the Ashkenazim settled on the Right. Paris’s first kosher inn opened in 1721 and its first synagogue opened in 1788. Anti-Jewish laws began to be repealed in the 1780's, such as the "body tax" which likened Jews to cattle. About 500 Jews were living in Paris and about 40,000 in France at the time of the French Revolution. The French Revolution After the French Revolution, citizenship was finally granted to the Jews of France. The Sephardim received citizenship in September 1790 and the Ashkenazim received it about six month later. Jews were given civic rights as individuals, but lost their group privileges. During the Reign of Terror (1793-94), synagogues and communal organizations were closed down, along with other religious institutions. Napoleon considered the Jews, "a nation with a nation," and he decided to create a Jewish communal structure sanctioned by the state. Hence, in 1806, he ordered the convening of a Grand Sanhedrin, composed of 45 rabbis and 26 laymen. The Grand Sanhedrin paved the way for the formation of the consistorial system, which were religious bodies established in every department of France that had a Jewish population numbering more than 2,000. The consistorial system made Judaism a recognized religion and placed it under government control. Despite the new found freedoms, anti-Jewish measures were passed in 1808. Napoleon declared all debts with Jews annulled, reduced or postponed, which caused the near ruin of the Jewish community. Restrictions were also placed on where Jews could live in an effort to assimilate them into French society. The Restoration The Jews did not receive the Restoration with any hostility. Jewish educational institutions were be established. In 1818, schools were opened in Metz, Strasbourg and Colmar. Other Jewish schools were opened in Bordeaux and Paris. The Metz Yeshiva, which was closed during the Revolution, was reopened as a central rabbinical seminary. The seminary was transferred to Paris in 1859, where it continues to function today. Judaism was given the same status as other recognized religions. During the 19th century, Jews were extremely active in many spheres of French society. Rachel and Sarah Bernhardt are two Jewish women who became famous acting at the Comedie Francaise in Paris. Bernhardt eventually directed plays at her own theater and was given the title "Divine Sarah" by Victor Hugo. Jews became involved in politics; for example, Achille Fould and Isaac Cremiuex served in the Chamber of Deputies. Jews also excelled in the financial sphere, two leading families were the Rothschild and the Pereire families. In the field of literature and philosophy, well-known Jews included Emile Durkheim, Marcel Proust and Salomon Munk. While the situation improved for Jews in France, the Damascus Affair served as a rude awakening. Accusation of a blood libel in Damascus led to an outbreak of anti-Jewish disorders in France in 1848. General unrest led to attacks in Alsace and spread northward, Jewish houses were pillaged and the army had to be sent in to resume order. The 1870 war transferred the Jewish communities of Alsace and Lorraine from French control to German control, a major loss for the Jewish community. An upsurge of anti-Semitism began in the late 1800's. Anti-Semitic newspapers were circulated, including Edouard Drumont’s La France Juive (1886), which became a best-seller. Jews were blamed for the collapse of the Union Generale, a leading Catholic bank. In this atmosphere, the infamous Dreyfus case was tried. Captain Alfred Dreyfus was arrested on October 15, 1894, for spying for Germany. He received a life sentence on Devil’s Island off the coast of South America. The government chose to repress evidence, which came to light through the writings of Emile Zola and Jean Jaures. Ten years later, the French government fell and Dreyfus was declared innocent. The Dreyfus case shocked Jewry worldwide and motivated Theodor Herzl to write the book "The Jewish State: A Modern Solution to the Jewish Question" in 1896. The Dreyfus case also led to the French law in 1905 separating church and state. JEWISH GENEALOGY RESEARCH IN FRANCE Ernest Kallmann

JEWISH SETTLEMENT IN FRANCE Jews have been documented in France since ancient times. Jews lived in Phoenician Marseilles before the Romans invaded Gaul. During the Middle Ages, they were periodically expelled and again allowed to return, until 1384, when some 100,000 Jews had to leave France, mostly to German speaking areas. For instance, Rashi spent a great part of his life in the town of Troyes around 1100 CE, growing wine grapes, teaching and commenting. Thereupon, there were no Jews any longer left in the Kingdom of France. But the Kingdom did not control the Papal states around Avignon, in the South West of France, where Jews could survive. Also, after the expulsion of the Jews from Spain and then Portugal in 1492, a number of "New Christians" emigrated to the southWest of France, mainly around Bayonne and Bordeaux. Though apparently assimilated and christianized, this "Portuguese Nation" maintained a hidden Jewish faith and practice. Besides these two French speaking communities, the largest number of Jews living on the territory of present France, the so-called German Jews, lived in Alsace, initially under the control of principalities of the Holy Roman Empire, and in Lorraine, around Metz. When France progressively took control of these provinces, a certain status quo was respected, though Jews were no citizens, not allowed to live in towns and were subjected to discriminatory taxes. On the other hand, Jewish communities could live according to their own rules, as long as the relations with the civil and Christian authorities remained as imposed. In 1791, during the French Revolution, Jews at once became citizens with the same rights and obligations as all other Frenchmen. They were allowed to settle where they wanted, mainly in larger cities where they could more easily earn a living. There have been two major waves of Jewish immigration, from the 1880ies to World War II, Eastern Europeans, and from 1950 to 1962, North Africans. The present Jewish population in France, estimated as 600,000 persons, includes a majority of people originating in Algeria, Tunisia and Morocco. CIVIL REGISTRATION The 1791 revolutionary, anti-clerical government abolished vital registration by the Church parishes and made civil registration compulsory for all. Thus, from September 1792 to now, Jews in France have their birth, marriage and death events registered in civil vital registers. The system devised at the time has remained in force without any modification; it was apparently perfect from the day of its inception. The administrative organization of France has also remained stable, the national territory being divided into Departements (presently 95 for Continental France, 2 for Corsica, and 5 for overseas colonies). Vital events are recorded in each town hall (Mairie). After 100 years, they are stored in the Departmental Archives (A.D.) located in the "chef-lieu" (the Departement "capital"). Civil registers exist since "Year One" of the French Revolution, (22 September 1792) and are generally available. There are exceptions, the most important being the Paris Town Archives before 1860, which were destroyed in 1871 during the Commune, a revolution. Though French has been the country's official language since the 16th century, early civil records in Alsace and part of Lorraine are in German (or rather what the local officer, who spoke the local dialect, thought was German). The script was Gothic and written as though by people for whom writing was not a current occupation. The same applies for all other documents in these places at that time; they require some practice to be deciphered and understood. ACCESS TO CIVIL VITAL RECORDS All records older than 100 years are accessible without restriction, as well as death records less than 100 years old. Birth and marriage records more recent than 100 years are in principle delivered only to direct descendants; a verbal declaration is sufficient. There are no administrative or photocopying fees. Index registers (Tables annuelles, tables decennales) From the inception of the Civil Records, and with exceptions only in the very first years and some small villages, yearly and decennial index tables have been in use for each birth, marriage or death register. The tables list the individuals alphabetically according to surnames and show given name, date of the event and serial or record number in the register. In the decennial register, events are often grouped year by year; thus, given names restart with A every year. The "tables annuelles" are usually located at the end of the year's records, the "tables decennales" after the records of the year ending with "2", e.g. 1882 for the 10-year period 1873- 1882.) So, for example, the last years of the 1903-1912 period are still within the 100-year period of limited access. Therefore it is too early yet to microfilm the registers and tables to make them easily available to the public. Physical location of the vital records 1. For the period beginning in 1903, the records and tables can only be found in the Mairie where they have been established. The Mairie provides photocopies of records well identified (name and date), and often will agree to do some research if the date is only approximate. Send a letter to the appropriate Mairie (Town Hall), give a date as accurate as possible, include a French stamp or an International Reply Coupon (2 if you wish to request a reply by air mail). For the online directory of postal codes of French Towns, see: http://www.france- codepostal.fr/en/ For the online Mormon (LDS) French letter-writing guide, see: http://www.familysearch.org 2. For the period prior to 1903, a copy of the records is kept at the Archives Departementales (A.D.). A.D.s do not perform research, nor do they provide copies of records. But access to all documents there is free, except for very ancient and fragile ones, where prior permission must be granted. If there are microfilms (60% of the archives are microfilmed), you may make a copy if you go there, or if somebody goes for you. Most microfilms existing in the A.Ds have been microfilmed by the Mormons and thus may also be viewed at any LDS Family History Center. One exception in Alsace (Haut-Rhin), is the "Centre Departemental d'Histoire des Familles" in Guebwiller, which may do research and send you a vital record for 60 FF (about $10). The preferred method of payment from overseas is an International Postal Money Order.

THE REPUBLICAN CALENDAR The French Republic, in keeping with the trend to decimalize all measures, also instituted a new calendar, comprised of 12 months of 30 days each, plus 5/6 "complementary days" at year-end. The names of the months and days were changed, and the week replaced by a 10-day decade, etc. The Republican calendar was in use from September 22, 1793 (though starting one year earlier) to January 1, 1806. The conversion from the Republican Calendar to Gregorian dates CIVIL CENSUS REPORTS In France, except for Paris and almost all the of the surrounding area, census reports are available from 1836 and every 5 years thereafter, until 1936, and then irregularly thereafter. Census reports for periods prior to 1903 are held by the Archives Departementales; for periods after 1903, the reports are held in the individual Mairies. These census reports are not indexed and have not been microfilmed. NOTARIAL ACTS (ACTES NOTARIES) When notarial acts are over 100 years old they are sent to the Archives Departementales, where they can be inspected, but not photocopied. However, sometimes they remain at the lawyer's office archive, where you can have them retrieved for you and even copied in some cases). After inception of civil vital registration, the existence of a pre-marriage contract was usually cited in the marriage record, with its date and the name of the notary in charge. Notary registration of the pre-marriage contract was compulsory for Jews in Alsace and Lorraine from the 18th century on. In addition to pre-marriage contracts, many other acts of daily life were registered by notaries, such as: purchase and sale of real estate, wills, IOUs, etc.

For further information, see:

"Mémoire Juive en Alsace: Contrats de mariage au XVIIIème siècle". Compiled by André-Aaron Fraenckel. 451+p. Editions du Cedrat, Strasbourg, 1997. ISBN 2- 95111121-0-6.

Index to "Mémoire Juive en Alsace...". Compiled by Rosanne et Daniel N. Leeson, Paris, 1999. ISBN 2-912785-10-3. 2 volumes. Tome 1 (Bas Rhin), 475 pages; tome 2 (Haut Rhin), 413 pages. THE PERIOD PRIOR TO 1792 With few exceptions, systematic registration of vital events was not in use prior to civil registration. Keeping registers of vital events is not part of the Jewish religious tradition. Therefore, other sources must be used. Names of the French Jews A further difficulty seems to originate in the Semitic use of names, where permanent names are the rule only for the descendants of the priests (Cohanim) and the Levites. For most of the people (beni Israel), the normal naming practice was to add the father's given name to the child's, e.g. David ben Moshe, whose father could be Moshe ben Efraim. In order to avoid the problems raised by this continuous change of second name, Napoleon, in a Decree given in 1808, ordered that all Jews adopt stable family names, a practice that was already in use in several places. In every town where Jews lived, these adoptions of names were registered at the Town Hall, and a great majority of the records have survived. They provide a bridge from present names to those in use prior to 1808. They also constitute a comprehensive, detailed census of the French Jewish population in 1808, allowing researchers to reconstruct the families. In fact, the head of the family registered himself first, then his wife, specifying that she was the spouse, and thereafter the father registered his children one at a time. When known, the birth date and birth place of the children may be present, and also, in some cases, the father's trade.

For further information, see:

"Recueils des déclarations de prise de noms patronymique des Juifs en 1808" by Pierre KATZ: Bas-Rhin ( 4 vol. 800 p.)., new edition, 1999. Haut-Rhin ( 2 vol. 401 p.), new ed. 1999 Moselle, Meurthe-et-Moselle (2ème edition 1999 - 1 vol. 320 p.).

Collections of the hereditary names chosen by Jews in 1808, showing older and new names.

OVERVIEW OF THE VARIOUS ZONES OF SETTLEMENT In each major zone of settlement, different conditions prevailed, each providing specific tools for genealogy research. For the sake of comparison, around 1789 some 5000 Jews lived in southwest France, 1800 in the southeast, and 1700 in various other cities, including Paris. In Lorraine, in and around the city of Metz, there were about 7000 Jews, and in Alsace about 23000. The early settlements in the SW and SE of France, though in limited size, played an important role in the history of French Jews. Having adopted French habits for a long time, they were able to rise both socially and economically. Their family histories have been kept over time, inasmuch as most families had a well-known personality within their ranks. The Jews in the Comtat Venaissin ("The Pope's Jews") These Jews lived mainly in 4 towns in the southeast: Cavaillon, Carpentras, L'Isle-sur-Sorgue and Avignon. The A.D., as well as the municipal archives, holds documents dating back to the 16th century. This rather limited population has been studied in great detail. A rich literature is available, mainly in French. The ancient documents, written in Latin or old French, are difficult for non-specialists to read.

THE PORTUGUESE NATION The Jews who left Portugal after 1496 (many had originated in Spain and had fled to Portugal shortly before) had to convert to Catholicism, and settled in southwest France as Catholics. They were called "new Christians" and often continued undercover Jewish practices. Church registers exist, mainly from the 17th century, with various documents similar to vital records for the 18th century. Additional information is available for those with connections to the Amsterdam Sephardic. In the Departement de la Gironde, the A.D.(in Bordeaux) and also the municipal archives hold various documents, mainly from the 17th and 18th century. In the Departement des Pyrenees Altantiques, the A.D. (in Pau) and the municipal archives also hold various documents (mainly 17th and 18th centuries). These documents have been catalogued. LORRAINE The French kingdom, after conquering the "three bishoprics" (Toul, Verdun and Metz) in the mid-16th century, favored the settlement of Jews in Metz. These Jews did not generally reach great wealth, but the community was a center of attraction for Jewish scholars. In the course of progressive conquest of the region, several communities were founded in small places, part of them speaking French, the other part German. Vital registration documents, as well as tax registers and notary deeds, are available for periods since the 18th century. In particular, marriage contracts (tenaim) registered with the Royal Notaries have been indexed. They are held in the A.D. du Departement de la Moselle (Metz) and also in municipal archives.

For further information, see: "Contrats de mariage juifs en Moselle avant 1792" par Jean FLEURY 2021 contrats de mariage notariés, (3e édition, 1999, 1 vol. 255 p.).. ISBN 2-9510092-5-9. Extraction of records from the civil registers.

"Tables du registre d'état civil de la communauté juive de Metz (1717-1792)", par Pierre-André MEYER. Republication in 1999 of the edition of 1987 by the author, comprising corrections included at the end of the volume and indicated in the text. 1 volume, 462 pages. From the religious records. ALSACE The largest settlement of Jews in France was in Alsace. They were spread out in hundreds of small village communities, as Jews were not allowed to live in towns. The villages near large towns, e.g. Bischheim next to Strasbourg, were the most populated, as the Jewish merchants did most of their business in the towns, entering them in the morning and leaving before curfew. In 1784, Louis XVI ordered a general census of all Jews in Alsace, which is available to researchers. Combined with the name adoption lists of 1808, the 1784 census forms a genealogical bridge from the 19th back to the 18th century. Louis XIV had ordered that all Jewish marriage contracts (t'naim) be filed with Royal Notaries. These contracts, in many cases, cover the whole 18th century.

For further information, see: "Le dénombrement des Juifs d'Alsace (1784)" (This is the new edition, published by the Cercle Genealogie Juive, taken from the original 1785 document in Strasbourg.) "Index to the Dénombrement des Juifs d'Alsace de 1784". Compiled by Daniel Leeson.

Various Other Sources The above summarizes what can be expected generally in each of the zones of settlement. Case by case, many other types of documents can help genealogy research. They usually require a sufficient command of the French language, if not also of Latin, Hebrew or even German. It is also often not permitted to photocopy these ancient documents, thus they can only be viewed on site in the Archives.

NATURALIZATIONS AND ASSOCIATED PROCEDURES There are 3 ways to become a French citizen : be born in France have at least one French parent request naturalization The naturalization file usually contains copies of the documents requested for the procedure, often including important genealogical material. Naturalization files are available to the public 60 years after the application was filed. Exceptions can be granted for special cases: academic research, or access to one's own file. After Alsace and Moselle were annexed by the German Empire in 1871, their inhabitants had the opportunity to move to France and there confirm/recover their French citizenship. In 1872/73, it was sufficient to live in France and to file an "option for the French nationality" to confirm one's citizenship. After 1873, sons of Alsace or Lorraine, French-born residents of France, could recover their French citizenship by applying for "re-integration". The corresponding files are similar to naturalization files. Files for naturalizations prior to 1900 are kept at the National Archives in Paris; 20th century files are in Fontainebleau (60 km SE of Paris). Option and re-integration files are kept in the Paris National Archives. Retrieving the files involves two steps: Identify the number and date of the decree granting naturalization, option or re- integration. The search instruments at the National Archives vary according to the period involved. Have the actual file retrieved, which takes several weeks.

The process of locating the numbers of the decree, etc., and using the varied indexes, are extremely complex and require a good knowledge of the system used. Then the wait time for receiving the actual files can be many weeks. Therefore, this is not something that can be done by mail from outside of France. These naturalizations can provide helpful genealogical information, but the services of an experienced local researcher are really a necessity. JEWISH RELIGIOUS SOURCES Since the time of Napoleon I, the administrative structure of the Jewish community is one "Consistoire" per Departement, and one national "Consistoire Central". Not only have no rules for maintaining files and archives been set, but many documents have been lost or destroyed. Finding a document is a rare opportunity. 1. Census Reports The Consistoire of Paris holds several census reports of Paris Jews: 1809, which had disappeared for a long time and was found some years ago in the USA. The Consistoire of Paris holds a copy. For each of the 2914 individuals, it lists given name, surname, address, year and place of birth. 1852, which contains only the head of household, the address, often the profession, sometimes the date of arrival in Paris. 1872, which is arranged by arrondissement, in alphabetical order (only for the first letter). It gives the surname, name, profession, and address for the head of household, the first name of the wife, and the number of minor sons and daughters. Only in the 11th arrondissement are the children named. 2. Marriages: Information is provided as certification of a religious marriage. Marriages have been recorded since 1823, stating surnames, given names (not always), addresses, class of marriages. After 1873, the dates and places of birth appear (not very precise). Not all marriages took place at a synagogue and thus were not recorded.

For further information, see: "Mariages religieux juifs à Paris, 1848-1872". Data compiled by Anne LIFSHITZ-KRAMS (3e édition, Paris 1999, 1 vol. 200p). ISBN 2- 9510092-0-8. 3. Death registers: The registers exist since 1882 and list surname, first name, name of the spouse, address, age, cemetery, class. Contact : Philippe LANDAU , directeur des Archives du Consistoire, 17 rue Saint Georges, 75009 PARIS, France. CEMETERIES There are specific Jewish cemeteries in Alsace, Lorraine and several other places in France. Generally, there used to be a Jewish plot (carre juif) in most general cemeteries. Recent burials may take place among non-Jewish neighbours. Information about a grave in a general cemetery is available from the local cemetery administration. For Paris and the surrounding area, unless you know which cemetery among the 8 possible cemeteries is involved, inquire with M. le Conservateur en Chef des Cimetieres de Paris, 16 rue du Repos, 75020 Paris. Give the name, the year of death, say that the deceased is an ascendant or a near relative, and give a reason for the inquiry. Always send an envelope with a stamp or an International postal coupon. For further information, see the IAJGS Cemetery Project for France. Many books of French cemetery listings are currently published, and more are to be published. For full information please see the link to Publications on the web site of the Cercle de Genealogie Juive.