7 More Logarithmic-Factor Speedups for 3SUM

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parameter-Free Locality Sensitive Hashing for Spherical Range Reporting˚

Parameter-free Locality Sensitive Hashing for Spherical Range Reporting˚ Thomas D. Ahle, Martin Aumüller, and Rasmus Pagh IT University of Copenhagen, Denmark, {thdy, maau, pagh}@itu.dk July 21, 2016 Abstract We present a data structure for spherical range reporting on a point set S, i.e., reporting all points in S that lie within radius r of a given query point q (with a small probability of error). Our solution builds upon the Locality-Sensitive Hashing (LSH) framework of Indyk and Motwani, which represents the asymptotically best solutions to near neighbor problems in high dimensions. While traditional LSH data structures have several parameters whose optimal values depend on the distance distribution from q to the points of S (and in particular on the number of points to report), our data structure is essentially parameter-free and only takes as parameter the space the user is willing to allocate. Nevertheless, its expected query time basically matches that of an LSH data structure whose parameters have been optimally chosen for the data and query in question under the given space constraints. In particular, our data structure provides a smooth trade-off between hard queries (typically addressed by standard LSH parameter settings) and easy queries such as those where the number of points to report is a constant fraction of S, or where almost all points in S are far away from the query point. In contrast, known data structures fix LSH parameters based on certain parameters of the input alone. The algorithm has expected query time bounded by Optpn{tqρq, where t is the number of points to report and ρ P p0; 1q depends on the data distribution and the strength of the LSH family used. -

On Range Searching with Semialgebraic Sets*

Discrete Comput Geom 11:393~,18 (1994) GeometryDiscrete & Computational 1994 Springer-Verlag New York Inc. On Range Searching with Semialgebraic Sets* P. K. Agarwal 1 and J. Matou~ek 2 1 Computer Science Department, Duke University, Durham, NC 27706, USA 2 Katedra Aplikovan6 Matamatiky, Universita Karlova, 118 00 Praka 1, Czech Republic and Institut fiir Informatik, Freie Universit~it Berlin, Arnirnallee 2-6, D-14195 Berlin, Germany matou~ek@cspguk 11.bitnet Abstract. Let P be a set of n points in ~d (where d is a small fixed positive integer), and let F be a collection of subsets of ~d, each of which is defined by a constant number of bounded degree polynomial inequalities. We consider the following F-range searching problem: Given P, build a data structure for efficient answering of queries of the form, "Given a 7 ~ F, count (or report) the points of P lying in 7." Generalizing the simplex range searching techniques, we give a solution with nearly linear space and preprocessing time and with O(n 1- x/b+~) query time, where d < b < 2d - 3 and ~ > 0 is an arbitrarily small constant. The acutal value of b is related to the problem of partitioning arrangements of algebraic surfaces into cells with a constant description complexity. We present some of the applications of F-range searching problem, including improved ray shooting among triangles in ~3 1. Introduction Let F be a family of subsets of the d-dimensional space ~d (d is a small constant) such that each y e F can be described by some fixed number of real parameters (for example, F can be the set of balls, or the set of all intersections of two ellipsoids, * Part of the work by P. -

New Data Structures for Orthogonal Range Searching

Alcom-FT Technical Report Series ALCOMFT-TR-01-35 New Data Structures for Orthogonal Range Searching Stephen Alstrup∗ The IT University of Copenhagen Glentevej 67, DK-2400, Denmark [email protected] Gerth Stølting Brodal† BRICS ‡ Department of Computer Science University of Aarhus Ny Munkegade, DK-8000 Arhus˚ C, Denmark [email protected] Theis Rauhe§ The IT University of Copenhagen Glentevej 67, DK-2400, Denmark [email protected] 5th April 2001 Abstract We present new general techniques for static orthogonal range searching problems in two and higher dimensions. For the general range reporting problem in R3, we achieve ε query time O(log n + k) using space O(n log1+ n), where n denotes the number of stored points and k the number of points to be reported. For the range reporting problem on ε an n n grid, we achieve query time O(log log n + k) using space O(n log n). For the two-dimensional× semi-group range sum problem we achieve query time O(log n) using space O(n log n). ∗Partially supported by a grant from Direktør Ib Henriksens Fond. †Partially supported by the IST Programme of the EU under contract number IST-1999-14186 (ALCOM- FT). ‡Basic Research in Computer Science, Center of the Danish National Research Foundation. §Partially supported by a grant from Direktør Ib Henriksens Fond. Part of the work was done while the author was at BRICS. 1 1 Introduction Let P be a finite set of points in Rd and Q a query range in Rd. Range searching is the problem of answering various types of queries about the set of points which are contained within the query range, i.e., the point set P Q. -

Range Searching

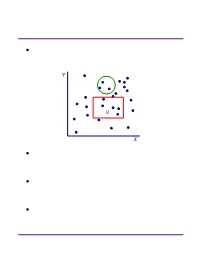

Range Searching ² Data structure for a set of objects (points, rectangles, polygons) for efficient range queries. Y Q X ² Depends on type of objects and queries. Consider basic data structures with broad applicability. ² Time-Space tradeoff: the more we preprocess and store, the faster we can solve a query. ² Consider data structures with (nearly) linear space. Subhash Suri UC Santa Barbara Orthogonal Range Searching ² Fix a n-point set P . It has 2n subsets. How many are possible answers to geometric range queries? Y 5 Some impossible rectangular ranges 6 (1,2,3), (1,4), (2,5,6). 1 4 Range (1,5,6) is possible. 3 2 X ² Efficiency comes from the fact that only a small fraction of subsets can be formed. ² Orthogonal range searching deals with point sets and axis-aligned rectangle queries. ² These generalize 1-dimensional sorting and searching, and the data structures are based on compositions of 1-dim structures. Subhash Suri UC Santa Barbara 1-Dimensional Search ² Points in 1D P = fp1; p2; : : : ; png. ² Queries are intervals. 15 71 3 7 9 21 23 25 45 70 72 100 120 ² If the range contains k points, we want to solve the problem in O(log n + k) time. ² Does hashing work? Why not? ² A sorted array achieves this bound. But it doesn’t extend to higher dimensions. ² Instead, we use a balanced binary tree. Subhash Suri UC Santa Barbara Tree Search 15 7 24 3 12 20 27 1 4 9 14 17 22 25 29 1 3 4 7 9 12 14 15 17 20 22 24 25 27 29 31 u v xlo =2 x hi =23 ² Build a balanced binary tree on the sorted list of points (keys). -

Further Results on Colored Range Searching

28:2 Further Results on Colored Range Searching colored range reporting: report all the distinct colors in the query range. colored “type-1” range counting: find the number of distinct colors in the query range. colored “type-2” range counting: report the number of points of color χ in the query range, for every color χ in the range. In this paper, we focus on colored range reporting and type-2 colored range counting. Note that the output size in both instances is equal to the number k of distinct colors in the range, and we aim for query time bounds that depend linearly on k, of the form O(f(n) + kg(n)). Naively using an uncolored range reporting data structure and looping through all points in the range would be too costly, since the number of points in the range can be significantly larger than k. 1.1 Colored orthogonal range reporting The most basic version of the problem is perhaps colored orthogonal range reporting: report the k distinct colors inside an orthogonal range (an axis-aligned box). It is not difficult to obtain an O(n polylog n)-space data structure with O(k polylog n) query time [22] for any constant dimension d: one approach is to directly modify the d-dimensional range tree [15, 43], and another approach is to reduce colored range reporting to uncolored range emptiness [26] (by building a one-dimensional range tree over the colors and storing a range emptiness structure at each node). Both approaches require O(k polylog n) query time rather than O(polylog n + k) as in traditional (uncolored) orthogonal range searching: the reason is that in the first approach, each color may be discovered polylogarithmically many times, whereas in the second approach, each discovered color costs us O(log n) range emptiness queries, each of which requires polylogarithmic time. -

Orthogonal Range Searching in Moderate Dimensions: K-D Trees and Range Trees Strike Back

Orthogonal Range Searching in Moderate Dimensions: k-d Trees and Range Trees Strike Back Timothy M. Chan∗ March 20, 2017 Abstract We revisit the orthogonal range searching problem and the exact `1 nearest neighbor search- ing problem for a static set of n points when the dimension d is moderately large. We give the first data structure with near linear space that achieves truly sublinear query time when the dimension is any constant multiple of log n. Specifically, the preprocessing time and space are O(n1+δ) for any constant δ > 0, and the expected query time is n1−1=O(c log c) for d = c log n. The data structure is simple and is based on a new \augmented, randomized, lopsided" variant of k-d trees. It matches (in fact, slightly improves) the performance of previous combinatorial al- gorithms that work only in the case of offline queries [Impagliazzo, Lovett, Paturi, and Schneider (2014) and Chan (SODA'15)]. It leads to slightly faster combinatorial algorithms for all-pairs shortest paths in general real-weighted graphs and rectangular Boolean matrix multiplication. In the offline case, we show that the problem can be reduced to the Boolean orthogonal vectors problem and thus admits an n2−1=O(log c)-time non-combinatorial algorithm [Abboud, Williams, and Yu (SODA'15)]. This reduction is also simple and is based on range trees. Finally, we use a similar approach to obtain a small improvement to Indyk's data structure [FOCS'98] for approximate `1 nearest neighbor search when d = c log n. 1 Introduction In this paper, we revisit some classical problems in computational geometry: d • In orthogonal range searching, we want to preprocess n data points in R so that we can detect if there is a data point inside any query axis-aligned box, or report or count all such points. -

Dynamic Orthogonal Range Searching on the RAM, Revisited∗

Dynamic Orthogonal Range Searching on the RAM, Revisited∗ Timothy M. Chan1 and Konstantinos Tsakalidis2 1 Department of Computer Science, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign [email protected] 2 Cheriton School of Computer Science, University of Waterloo, Canada [email protected] Abstract We study a longstanding problem in computational geometry: 2-d dynamic orthogonal range log n reporting. We present a new data structure achieving O log log n + k optimal query time and O log2/3+o(1) n update time (amortized) in the word RAM model, where n is the number of data points and k is the output size. This is the first improvement in over 10 years of Mortensen’s previous result [SIAM J. Comput., 2006], which has O log7/8+ε n update time for an arbitrarily small constant ε. In the case of 3-sided queries, our update time reduces to O log1/2+ε n , improving Wilkin- son’s previous bound [ESA 2014] of O log2/3+ε n . 1998 ACM Subject Classification “F.2.2 Nonnumerical Algorithms and Problems” Keywords and phrases dynamic data structures, range searching, computational geometry Digital Object Identifier 10.4230/LIPIcs.SoCG.2017.28 1 Introduction Orthogonal range searching is one of the most well-studied and fundamental problems in computational geometry: the goal is to design a data structure to store a set of n points so that we can quickly report all points inside a query axis-aligned rectangle. In the “emptiness” version of the problem, we just want to decide if the rectangle contains any point. -

Solving Database Queries Using Orthogonal Range Searching

SOLVING DATABASE QUERIES USING ORTHOGONAL RANGE SEARCHING CPS234: Computational Geometry | Prof. Pankaj Agarwal Prepared by: Khalid Al Issa ([email protected]) Fall 2005 BACKGROUND : RANGE SEARCHING, a database-oriented view Range searching is the side of geometry science in which a set of items is analyzed to determine the subset that belong to a given “range”. In other words, we are given as an input a set of elements with certain properties, and we are also given a “range” of properties. So, our output is expected to be “the set of elements whose properties exist in the given range”. In mathematical notation, we have: INPUT: P : {P0, P1, P2,.. , Pn} a set of elements with given properties (ex. weights..etc) Q : a range of properties (ex. Weights between x and y) OUTPUT: The set of elements that belong in the “intersection” of P and Q. Database queries happen to be a major application in which theories of range searching are applied. Let’s take an example of a database query, and interpret it in geometrical form: Assume we have a database for students’ records, in which we keep every student’s ID, name, number of completed hours, and the cumulative GPA. We now would like to apply the following SQL query to the database: SQL> SELECT ID,NAME FROM STUDENTS WHERE HOURS BETWEEN 75 AND 90 AND GPA BETWEEN 2.5 AND 3.0 Figure.1: Range searching for a 2-D query 1 So this query above will give us the ID and name of every student whose GPA lies in the range [2.5,3.0] AND who has successfully completed hours in the range [75,90]. -

Further Results on Colored Range Searching Timothy M

Further Results on Colored Range Searching Timothy M. Chan Department of Computer Science, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, IL, USA [email protected] Qizheng He Department of Computer Science, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, IL, USA [email protected] Yakov Nekrich Department of Computer Science, Michigan Technological University, Houghton, MI, USA [email protected] Abstract We present a number of new results about range searching for colored (or “categorical”) data: 1. For a set of n colored points in three dimensions, we describe randomized data structures with O(n polylog n) space that can report the distinct colors in any query orthogonal range (axis-aligned box) in O(k polyloglog n) expected time, where k is the number of distinct colors in the range, assuming that coordinates are in {1, . , n}. Previous data structures require log n O( log log n + k) query time. Our result also implies improvements in higher constant dimensions. 2. Our data structures can be adapted to halfspace ranges in three dimensions (or circular ranges in two dimensions), achieving O(k log n) expected query time. Previous data structures require O(k log2 n) query time. 3. For a set of n colored points in two dimensions, we describe a data structure with O(n polylog n) space that can answer colored “type-2” range counting queries: report the number of occurrences log n of every distinct color in a query orthogonal range. The query time is O( log log n + k log log n), where k is the number of distinct colors in the range. -

Orthogonal Range Searching on the RAM, Revisited

Orthogonal Range Searching on the RAM, Revisited Timothy M. Chan∗ Kasper Green Larsen† Mihai Pˇatras¸cu‡ March 30, 2011 Abstract We present a number of new results on one of the most extensively studied topics in computational geometry, orthogonal range searching. All our results are in the standard word RAM model: 1. We present two data structures for 2-d orthogonal range emptiness. The first achieves O(n lg lg n) space and O(lg lg n) query time, assuming that the n given points are in rank space. This improves ε the previous results by Alstrup, Brodal, and Rauhe (FOCS’00), with O(n lg n) space and O(lg lg n) query time, or with O(n lg lg n) space and O(lg2 lg n) query time. Our second data structure uses ε O(n) space and answers queries in O(lg n) time. The best previous O(n)-space data structure, due to Nekrich (WADS’07), answers queries in O(lg n/ lg lg n) time. ε 2. We give a data structure for 3-d orthogonal range reporting with O(n lg1+ n) space and O(lg lg n+ k) query time for points in rank space, for any constant ε> 0. This improves the previous results by Afshani (ESA’08), Karpinski and Nekrich (COCOON’09), and Chan (SODA’11), with O(n lg3 n) ε space and O(lg lg n + k) query time, or with O(n lg1+ n) space and O(lg2 lg n + k) query time. Consequently, we obtain improved upper bounds for orthogonal range reporting in all constant di- mensions above 3. -

Lecture 8: Orthogonal Range Searching 8.1 Range Searching 8.2

CPS234 Computational Geometry September 22nd, 2005 Lecture 8: Orthogonal Range Searching Lecturer: Pankaj K. Agarwal Scribe: Mason F. Matthews 8.1 Range Searching The general problem of range searching is as follows: Given input S, a set of n points in Rd, preprocess the data into a data structure (if necessary) and answer a series of queries about the data. Queries include a d-dimensional region r and may be any of the following types: • Emptiness: Does r ∩ S = ∅? The output will be boolean. • Reporting: Output r ∩ S. The output will be a subset of S. • Counting: Compute |r ∩ S|. The output will be an integer. Since solving the reporting problem provides an answer to the other two queries, this will be our focus. In the broadest sense, these regions can have any form, but if it is assumed that region inclusion can be computed in constant time, the naive algorithm of checking every point can be run in O(n) time for each query. In the database community, these problems are known as “indexing” problems, and any preprocessing of the input into a data structure is referred to as “building an index.” 8.2 Orthogonal Range Searching Suppose instead that our queries are limited to d-dimensional axis-aligned rectangles, input as the cross- product of 1-D intervals (i.e. r = [a1, b1] × [a2, b2] × ... × [ad, bd]). Queries of this form are referred to as rectangular range queries, or more commonly in computational geometry as orthogonal range queries. With this restriction in place, the naive query time is still O(n), but now a wide range of data structures can be used to speed the process. -

R-Trees: Introduction

1. Introduction The paper entitled “The ubiquitous B-tree” by Comer was published in ACM Computing Surveys in 1979 [49]. Actually, the keyword “B-tree” was standing as a generic term for a whole family of variations, namely the B∗-tree, the B+-tree and several other variants [111]. The title of the paper might have seemed provocative at that time. However, it represented a big truth, which is still valid now, because all textbooks on databases or data structures devote a considerable number of pages to explain definitions, characteristics, and basic procedures for searches, inserts, and deletes on B-trees. Moreover, B+-trees are not just a theoretical notion. On the contrary, for years they have been the de facto standard access method in all prototype and commercial relational systems for typical transaction processing applications, although one could observe that some quite more elegant and efficient structures have appeared in the literature. The 1980s were a period of wide acceptance of relational systems in the market, but at the same time it became apparent that the relational model was not adequate to host new emerging applications. Multimedia, CAD/CAM, geo- graphical, medical and scientific applications are just some examples, in which the relational model had been proven to behave poorly. Thus, the object- oriented model and the object-relational model were proposed in the sequel. One of the reasons for the shortcoming of the relational systems was their inability to handle the new kinds of data with B-trees. More specifically, B- trees were designed to handle alphanumeric (i.e., one-dimensional) data, like integers, characters, and strings, where an ordering relation can be defined.