The Indian Premier League and World Cricket

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Captain Cool: the MS Dhoni Story

Captain Cool The MS Dhoni Story GULU Ezekiel is one of India’s best known sports writers and authors with nearly forty years of experience in print, TV, radio and internet. He has previously been Sports Editor at Asian Age, NDTV and indya.com and is the author of over a dozen sports books on cricket, the Olympics and table tennis. Gulu has also contributed extensively to sports books published from India, England and Australia and has written for over a hundred publications worldwide since his first article was published in 1980. Based in New Delhi from 1991, in August 2001 Gulu launched GE Features, a features and syndication service which has syndicated columns by Sir Richard Hadlee and Jacques Kallis (cricket) Mahesh Bhupathi (tennis) and Ajit Pal Singh (hockey) among others. He is also a familiar face on TV where he is a guest expert on numerous Indian news channels as well as on foreign channels and radio stations. This is his first book for Westland Limited and is the fourth revised and updated edition of the book first published in September 2008 and follows the third edition released in September 2013. Website: www.guluzekiel.com Twitter: @gulu1959 First Published by Westland Publications Private Limited in 2008 61, 2nd Floor, Silverline Building, Alapakkam Main Road, Maduravoyal, Chennai 600095 Westland and the Westland logo are the trademarks of Westland Publications Private Limited, or its affiliates. Text Copyright © Gulu Ezekiel, 2008 ISBN: 9788193655641 The views and opinions expressed in this work are the author’s own and the facts are as reported by him, and the publisher is in no way liable for the same. -

This Is Disturbing: Andre Russell on Picture of Cop Pointing Rubber- Bullet Gun at a Child During US Protests

6/2/2020 This is disturbing: Andre Russell on picture of cops pointing rubber-bullet gun at a child during US protests | Sports News This is disturbing: Andre Russell on picture of cop pointing rubber- bullet gun at a child during US protests Others TN Sports Desk Updated Jun 02, 2020 | 19:09 IST West Indies all-rounder Andre Russell shared a picture of a cop pointing a rubber-bullet gun at a child during the ongoing protests over George Floyd's death in the United States. KEY HIGHLIGHTS Andre Russell on Tuesday shared a picture of a cop in the United States pointing a rubber- bullet gun at a child Andre Russell said he was disturbed by the picture which is from the ongoing protests in the US over George Floyd's death Several cricketers and footballers have joined the 'Black lives matter' campaign on social media Andre Russell said he was disturbed by the viral photo. | @ar12russell | | Photo Credit: Instagram West Indies all-rounder Andre Russell on Tuesday took to social media to share a picture of a cop in the United States pointing a rubber-bullet gun at a child during the ongoing protests over George Floyd's death. The forty-six-year-old died in Minneapolis, Minnesota on May 25 aer a police officer kneeled on his neck for over eight minutes. The tragic passing away of Floyd has sparked massive outrage across the United States as people are protesting over his death. At least 4 police officers have been suspended by the authorities and people are demanding that all four should be charged for murder. -

Sarwan: WICB Nails Canards

Friday 22nd April 2011 13 The West Indies Cricket Board issued him the necessary No Objection Certificate (NOC), but issued a media release critical of Gayle’s choice. Gayle said the dispute Sophia Vergara predates the World Cup, claiming he was She has the looks and the curvaceous threatened with body that could kill, and he is one of the exclusion from most famous faces in the world. the tournament So it is no wonder that Pepsi chose for asking Modern Family star Sophia Vergara and whether the Beckham and footballer David Beckham, 35, to team up tournament and star in their latest advertising cam- contract was swimsuit-clad paign. approved by In the 30-second advertisement, the 38- the West year-old old Colombian suns herself in a Indies Vergara debut low-cut electric one-piece swimsuit. Players’ She spots a young girl sipping a can of Association. their first ever Pepsi and immediately craves the soft “I got a drink. reply, copied to Pepsi commercial Getting a glimpse of the long line at the refreshment booth, she takes to Twitter to craftily dupe the crowd. Dangerous curves In the 31 second advertisement, the 38- Gayle claims forced year-old old Colombian suns herself in a low-cut electric one-piece swimsuit Immediately beach-goers hurtle away from the drink stand in a bid to find the famous footballer, making way for the stun- ning brunette to purchase her much need- to skip Pakistan series ed refreshment. Getting up from her lounge, she gives viewers a glimpse of her stunning behind CASTRIES (St. -

Will T20 Clean Sweep Other Formats of Cricket in Future?

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Will T20 clean sweep other formats of Cricket in future? Subhani, Muhammad Imtiaz and Hasan, Syed Akif and Osman, Ms. Amber Iqra University Research Center 2012 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/45144/ MPRA Paper No. 45144, posted 16 Mar 2013 09:41 UTC Will T20 clean sweep other formats of Cricket in future? Muhammad Imtiaz Subhani Iqra University Research Centre-IURC , Iqra University- IU, Defence View, Shaheed-e-Millat Road (Ext.) Karachi-75500, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (92-21) 111-264-264 (Ext. 2010); Fax: (92-21) 35894806 Amber Osman Iqra University Research Centre-IURC , Iqra University- IU, Defence View, Shaheed-e-Millat Road (Ext.) Karachi-75500, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (92-21) 111-264-264 (Ext. 2010); Fax: (92-21) 35894806 Syed Akif Hasan Iqra University- IU, Defence View, Shaheed-e-Millat Road (Ext.) Karachi-75500, Pakistan E-mail: [email protected] Tel: (92-21) 111-264-264 (Ext. 1513); Fax: (92-21) 35894806 Bilal Hussain Iqra University Research Centre-IURC , Iqra University- IU, Defence View, Shaheed-e-Millat Road (Ext.) Karachi-75500, Pakistan Tel: (92-21) 111-264-264 (Ext. 2010); Fax: (92-21) 35894806 Abstract Enthralling experience of the newest format of cricket coupled with the possibility of making it to the prestigious Olympic spectacle, T20 cricket will be the most important cricket format in times to come. The findings of this paper confirmed that comparatively test cricket is boring to tag along as it is spread over five days and one-days could be followed but on weekends, however, T20 cricket matches, which are normally played after working hours and school time in floodlights is more attractive for a larger audience. -

IPL 2014 Schedule

Page: 1/6 IPL 2014 Schedule Mumbai Indians vs Kolkata Knight Riders 1st IPL Sheikh Zayed Stadium, Abu Dhabi Apr 16, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Delhi Daredevils vs Royal Challengers Bangalore 2nd IPL Sharjah Cricket Association Stadium, Sharjah Apr 17, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Chennai Super Kings vs Kings XI Punjab 3rd IPL Sheikh Zayed Stadium, Abu Dhabi Apr 18, 2014 | 14:30 local | 10:30 GMT Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Rajasthan Royals 4th IPL Sheikh Zayed Stadium, Abu Dhabi Apr 18, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Royal Challengers Bangalore vs Mumbai Indians 5th IPL Dubai International Cricket Stadium, Dubai Apr 19, 2014 | 14:30 local | 10:30 GMT Kolkata Knight Riders vs Delhi Daredevils 6th IPL Dubai International Cricket Stadium, Dubai Apr 19, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Rajasthan Royals vs Kings XI Punjab 7th IPL Sharjah Cricket Association Stadium, Sharjah Apr 20, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Chennai Super Kings vs Delhi Daredevils 8th IPL Sheikh Zayed Stadium, Abu Dhabi Apr 21, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Kings XI Punjab vs Sunrisers Hyderabad 9th IPL Sharjah Cricket Association Stadium, Sharjah Apr 22, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Rajasthan Royals vs Chennai Super Kings 10th IPL Dubai International Cricket Stadium, Dubai Apr 23, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Royal Challengers Bangalore vs Kolkata Knight Riders Page: 2/6 11th IPL Sharjah Cricket Association Stadium, Sharjah Apr 24, 2014 | 18:30 local | 14:30 GMT Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Delhi Daredevils 12th IPL Dubai International Cricket Stadium, Dubai Apr 25, 2014 -

Best Sports Venues in Mumbai"

"Best Sports Venues in Mumbai" Erstellt von : Cityseeker 5 Vorgemerkte Orte SMAAASH "All About Sports, Fun & Games" Smaaash, stands true to its name and is a smashing hit amongst sport aficionados. This spacious venue promises an unlimited fun and a great time. This one-of-a-kind place offers sports-oriented entertainment and gaming options. Cricket lovers can try their hand at the cricket simulator, where bowling machines throw challenges at you; bowling fans can go for by battlecreekcvb the bowling alleys. That's not it, you can also enjoy motor racing, hoopla zone, laser maze, paintball war and so forth. And, if action is not for you, simply head to the on-site spa and rejuvenate yourself, while your kids enjoy. When it's a fun zone, it has to have great dining options too, at the Bazinga Sports Cafe you can indulge in comfort food like burgers or simply go for Indian dishes. With such great activities and atmosphere, Smaaash is an ideal venue for hosting your party or event. For reservations and other details, call ahead. +91 22 4914 3143 smaaash.in/ [email protected] Pandurang Budhkar Marg, City Studio, Gate 4, Oasis Complex, Mumbai Mahalaxmi Race Course (Royal Western India Turf Club) "Breathing Space!" Accessible from both the Haji Ali sea-face and Keshavrao Khadye Marg, this world-class turf club and racecourse was built under the enthusiastic direction of Major E Hughes in 1880. The Mahalaxmi racecourse is open throughout the year for the general public and most visitors come for a jog around the 2.2km inner circuit, only to regain the lost calories at Gallops. -

Pushpinder Singh Saints & Warriors’ Founder Goes Back in Time

August 16-31, 2012 Volume 1, Issue 7 `100 22 DEFINING MOMENTS Pushpinder Singh Saints & Warriors’ founder goes back in time. 26 Can targeted programming make the youth fall in love with television all over again? NEROLAC Tuning in Fully The paints company is Elusive Audience thinking social media. 40 PROFILE 32 Sudha Natrajan The Lintas long timer branches out on her own. AFAQS! INITIATIVES Double Bill 34 PHILIPS Stepping out in Style 50 9XM Appetiser to Happytizer 51 UNINOR Small is Better 51 EDITORIAL This fortnight... Volume 1, Issue 7 EDITOR Sreekant Khandekar ornstar-turned-television star-turned Bollywood actor, Sunny Leone, recently made a statement PUBLISHER Pin the media – I think the young generation of people are ready to see someone like me on Prasanna Singh TV. She was referring to the reality show Bigg Boss in which she participated as an inmate in the EXECUTIVE EDITOR Bigg Boss house. Prajjal Saha SENIOR LAYOUT ARTIST Well that could be one side of the story, but the fact is what Indian youth Vinay Dominic wants to watch on television is open to debate . Until a few years ago, such was PRODUCTION EXECUTIVE Andrias Kisku August 16-31, 2012 Volume 1, Issue 7 `100 the impact of media that there was an entire generation which grew up as the 22 MTV/Channel V generation. At that time, the variety of content was limited ADVERTISING ENQUIRIES Neha Arora, (0120) 4077866, 4077837 and music was the only way to click with the youth. However, unfortunately the Noida DEFINING MOMENTS Pushpinder Singh television channels weren’t able to hold on to this audience for long. -

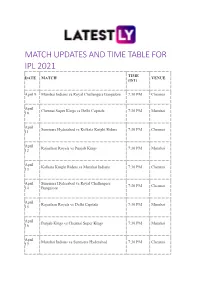

Match Updates and Time Table for Ipl 2021 Time Date Match Venue (Ist)

MATCH UPDATES AND TIME TABLE FOR IPL 2021 TIME DATE MATCH VENUE (IST) April 9 Mumbai Indians vs Royal Challengers Bangalore 7:30 PM Chennai April Chennai Super Kings vs Delhi Capitals 7:30 PM Mumbai 10 April Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Kolkata Knight Riders 7:30 PM Chennai 11 April Rajasthan Royals vs Punjab Kings 7:30 PM Mumbai 12 April Kolkata Knight Riders vs Mumbai Indians 7:30 PM Chennai 13 April Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Royal Challengers 7:30 PM Chennai 14 Bangalore April Rajasthan Royals vs Delhi Capitals 7:30 PM Mumbai 15 April Punjab Kings vs Chennai Super Kings 7:30 PM Mumbai 16 April Mumbai Indians vs Sunrisers Hyderabad 7:30 PM Chennai 17 April Royal Challengers Bangalore vs Kolkata Knight 3:30 PM Chennai 18 Riders April Delhi Capitals vs Punjab Kings 7:30 PM Mumbai 18 April Chennai Super Kings vs Rajasthan Royals 7:30 PM Mumbai 19 April Delhi Capitals vs Mumbai Indians 7:30 PM Chennai 20 April Punjab Kings vs Sunrisers Hyderabad 3:30 PM Chennai 21 April Kolkata Knight Riders vs Chennai Super Kings 7:30 PM Mumbai 21 April Royal Challengers Bangalore vs Rajasthan Royals 7:30 PM Mumbai 22 April Punjab Kings vs Mumbai Indians 7:30 PM Chennai 23 April Rajasthan Royals vs Kolkata Knight Riders 7:30 PM Mumbai 24 April Chennai Super Kings vs Royal Challengers 3:30 PM Mumbai 25 Bangalore April Sunrisers Hyderabad vs Delhi Capitals 7:30 PM Chennai 25 April Punjab Kings vs Kolkata Knight Riders 7:30 PM Ahmedabad 26 April Delhi Capitals vs Royal Challengers Bangalore 7:30 PM Ahmedabad 27 April Chennai Super Kings vs Sunrisers Hyderabad 7:30 -

Match Report

Match Report Mumbai Indians, Mumbai Indians vs Royal Challengers Bangalore, Royal Challengers Bangalore Mumbai Indians, Mumbai Indians Won Date: Tue 06 May 2014 Location: India - Maharashtra Match Type: Twenty20 Scorer: Sreenath Puthiyedath Toss: Royal Challengers Bangalore, Royal Challengers Bangalore won the toss and elected to Bowl URL: http://www.crichq.com/matches/136442 Mumbai Indians, Mumbai Royal Challengers Bangalore, Indians Royal Challengers Bangalore Score 187-5 Score 168-8 Overs 20.0 Overs 20.0 BR Dunk CH Gayle CM Gautam PA Patel AT Rayudu V Kohli* RG Sharma* R Rossouw CJ Anderson AB de Villiers KA Pollard Y Singh AP Tare MA Starc H Singh HV Patel PS Suyal AB Dinda JJ Bumrah VR Aaron SL Malinga YS Chahal page 1 of 34 Scorecards 1st Innings | Batting: Mumbai Indians, Mumbai Indians R B 4's 6's SR BR Dunk . 1 2 . 4 1 4 2 . 1 . // c Y Singh b HV Patel 15 14 2 0 107.14 CM Gautam . 4 1 1 . 6 . 6 . 4 . 1 . 6 . 1 . // c PA Patel b VR Aaron 30 28 2 3 107.14 AT Rayudu 1 1 . 1 1 4 1 . // b AB Dinda 9 9 1 0 100.0 RG Sharma* . 1 1 1 1 . 1 . 1 . 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 . 1 1 4 . 1 6 1 6 4 6 2 6 . 1 2 4 not out 59 35 3 4 168.57 CJ Anderson . 6 . // c V Kohli* b YS Chahal 6 4 0 1 150.0 KA Pollard . 1 4 1 . 1 1 4 . -

Sports Terminologies & List of Sports Trophies/Cups

www.gradeup.co 1 www.gradeup.co Sports Terminologies Sports Terminology Service, Deuce, Smash, Drop, Let, Game, Love, Double Badminton Fault. Baseball Pitcher, Strike, Diamond, Bunting, Home Run, Put Out. Alley-oop, Dunk, Box-Out, Carry the Ball, Cherry Picking, Basketball Lay-up, Fast Break, Traveling Jigger, Break, Scratch, Cannons, Pot, Cue, In Baulk, Pot Billiards Scratch, In Off. Boxing Jab, Hook, Punch, Knock-out, Upper cut, Kidney Punch. Revoke, Ruff, Dummy, Little Slam, Grand Slam, Trump, Bridge Diamonds, Tricks. Chess Gambit, Checkmate, Stalemate, Check. LBW, Maiden over, Rubber, Stumped, Ashes, Hat-trick, Leg Bye, follow on, Googly, Gulley, Silly Point, Duck, Run, Cricket Drive, no ball, Cover point, Leg Spinner, Wicket Keeper, Pitch, Crease, Bowling, Leg-Break, Hit – Wicket, Bouncer, Stone-Walling. Dribble, Off-Side, Penalty, Throw-in, Hat-Trick, Foul, Football Touch, Down, Drop Kick, Stopper Hole, Bogey, Put, Stymie, Caddie, Tee, Links, Putting the Golf green. Bully, Hat-Trick, Short corner, Stroke, Striking Circle, Hockey Penalty corner, Under cutting, Scoop, Centre forward, Carry, Dribble, Goal, Carried. Horse Racing Punter, Jockey, Place, Win, Protest. Volley, Smash, Service, Back-hand-drive,Let, Advantage, Lawn Tennis Deuce Shooting Bag, Plug, Skeet, Bull's eye Swimming Stroke. Table Tennis Smash, Drop, Deuce, Spin, Let, Service Volley Ball Blocking, Doubling, Smash, Point, Serve, Volley Wrestling Freestyle, Illegal Hold, Nearfall, Clamping 2 www.gradeup.co List of Sports Trophies/ Cups Sports Trophies/ Cups Ashes Cup, Asia Cup, C.K. Naidu Trophy, Deodhar Trophy, Duleep Trophy, Gavaskar Border Trophy, G.D. Birla Trophy, Gillette Cup, ICC World Cup, Irani Trophy, Jawaharlal Nehru Cup, Cricket Rani Jhansi Trophy, Ranji Trophy, Rohinton Barcia Trophy, Rothmans Cup, Sahara Cup, Sharjah Cup, Singer Cup, Titan Cup, Vijay Hazare Trophy, Vijay Merchant Trophy, Wisden Trophy, Wills Trophy. -

Balance Sheet Merge Satistics & Color Bitmap.Cdr

MADHYA PRADESH CRICKET ASSOCIATION Holkar Stadium, Khel Prashal, Race Course Road, INDORE-452 003 (M.P.) Phone : (0731) 2543602, 2431010, Fax : (0731) 2534653 e-mail : [email protected] Date : 17th Aug. 2011 MEETING NOTICE To, All Members, Madhya Pradesh Cricket Association. The Annual General Body Meeting of Madhya Pradesh Cricket Association will be held at Holkar Stadium, Khel Prashal, Race Course Road, Indore on 3rd September 2011 at 12 Noon to transact the following business. A G E N D A 1. Confirmation of the minutes of the previous Annual General Body Meeting held on 22.08.2010. 2. Adoption of Annual Report for 2010-2011. 3. Consideration and approval of Audited Statement of accounts and audit report for the year 2010-2011. 4. To consider and approve the Proposed Budget for the year 2011-2012. 5. Appointment of the Auditors for 2011-2012. 6. Any other matter with the permission of the Chair. (NARENDRA MENON) Hon. Secretary Note : 1. If you desire to seek any information, you are requested to write to Hon. Secretary latest by 28th Aug. 2011. 2. The Quorum for meeting is One Third of the total membership. If no quorum is formed, the Meeting will be adjourned for 15 minutes. No quorum will be necessary for adjourned meeting. The adjourned meeting will be held at the same place. THE MEETING WILL BE FOLLOWED BY LUNCH. 1 MADHYA PRADESH CRICKET ASSOCIATION, INDORE UNCONFIRMED MINUTES OF ANNUAL GENERAL BODY MEETING HELD ON 22nd AUGUST 2010 A meeting of the General Body of MPCA was held on Sunday 22nd Aug’ 2010 at Usha Raje Cricket Centre at 12.00 noon. -

Coaches Optimistic of a Result Oriented Clash by REEMUS FERNANDO Bringing Back Memories of His Good Batting Performance of the Past Big the Coaches of St

Thursday 1st March, 2012 78th Battle of the Saints Coaches optimistic of a result oriented clash BY REEMUS FERNANDO bringing back memories of his good batting performance of the past big The coaches of St. Joseph’s match. College, Darley Road and St. Peter’s While stressing the importance of College, Bambalapitiya are looking going for a result, Ramanayake was forward to a result oriented clash hopeful that spinner Supeshala when the two school teams meet in Jayathilaka would use his reserved the annual cricket Big Match at P. energy to trouble Petes. “We did not Sara grounds on Friday and Saturday. burden him much during the season Despite collapsing for low scores as he was also attending Sri Lanka on a couple of occasions and conced- Under-19 training. He will be ready to ing a defeat once this season, Keerthi deliver at the Big Match,” said Gunaratne believes that his team has Ramanayake. enough firepower to pull off a victory The annual encounter has pro- Sachin Tendulkar and said that his team would come up duced two results during the last four with a positive frame of mind for the years after a long phase of draws that 78th edition of this annual encounter. bored the series. The results pro- Sachin Tendulkar “We may have failed on a couple of duced during recent times have occasions. But we have enough mate- increased the spectator interest in the named in India rial to fight for a result. We are keen ‘Battle of the Saints’ and the two on fighting for a result,” Gunaratne Dilan Ramanayake Keerthi Gunaratne teams are entrusted with that task of told The Island.