Chicago Physics One

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

R Mathematics Esearch Eports

Mathematics r research reports M r Boris Hasselblatt, Svetlana Katok, Michele Benzi, Dmitry Burago, Alessandra Celletti, Tobias Holck Colding, Brian Conrey, Josselin Garnier, Timothy Gowers, Robert Griess, Linus Kramer, Barry Mazur, Walter Neumann, Alexander Olshanskii, Christopher Sogge, Benjamin Sudakov, Hugh Woodin, Yuri Zarhin, Tamar Ziegler Editorial Volume 1 (2020), p. 1-3. <http://mrr.centre-mersenne.org/item/MRR_2020__1__1_0> © The journal and the authors, 2020. Some rights reserved. This article is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ Mathematics Research Reports is member of the Centre Mersenne for Open Scientific Publishing www.centre-mersenne.org Mathema tics research reports Volume 1 (2020), 1–3 Editorial This is the inaugural volume of Mathematics Research Reports, a journal owned by mathematicians, and dedicated to the principles of fair open access and academic self- determination. Articles in Mathematics Research Reports are freely available for a world-wide audi- ence, with no author publication charges (diamond open access) but high production value, thanks to financial support from the Anatole Katok Center for Dynamical Sys- tems and Geometry at the Pennsylvania State University and to the infrastructure of the Centre Mersenne. The articles in MRR are research announcements of significant ad- vances in all branches of mathematics, short complete papers of original research (up to about 15 journal pages), and review articles (up to about 30 journal pages). They communicate their contents to a broad mathematical audience and should meet high standards for mathematical content and clarity. The entire Editorial Board approves the acceptance of any paper for publication, and appointments to the board are made by the board itself. -

Harry Truman, the Atomic Bomb and the Apocalyptic Narrative

Volume 5 | Issue 7 | Article ID 2479 | Jul 12, 2007 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus The Decision to Risk the Future: Harry Truman, the Atomic Bomb and the Apocalyptic Narrative Peter J. Kuznick The Decision to Risk the Future: Harry stressed that the future of mankind would be Truman, the Atomic Bomb and theshaped by how such bombs were used and Apocalyptic Narrative subsequently controlled or shared.[3] Truman recalled Stimson “gravely” expressing his Peter J. Kuznick uncertainty about whether the U.S. should ever use the bomb, “because he was afraid it was so I powerful that it could end up destroying the whole world.” Truman admitted that, listening In his personal narrative Atomic Quest, Nobel to Stimson and Groves and reading Groves’s Prize-winning physicist Arthur Holly Compton, accompanying memo, he “felt the same who directed atomic research at the University fear.”[4] of Chicago’s Metallurgical Laboratory during the Second World War, tells of receiving an urgent visit from J. Robert Oppenheimer while vacationing in Michigan during the summer of 1942. Oppenheimer and the brain trust he assembled had just calculated the possibility that an atomic explosion could ignite all the hydrogen in the oceans or the nitrogen in the atmosphere. If such a possibility existed, Compton concluded, “these bombs must never be made.” As Compton said, “Better to accept the slavery of the Nazis than to run a chance of drawing the final curtain on mankind.”[1] Certainly, any reasonable human being could be expected to respond similarly. Three years later, with Hitler dead and the Nazis defeated, President Harry Truman faced Truman and Byrnes en route to Potsdam, July a comparably weighty decision. -

Atomic Physics & Quantum Effects

KEY CONCEPTS ATOMIC PHYSICS & QUANTUM EFFECTS 1. PHOTONS & THE PHOTOELECTRIC EFFECT Max Planck explained blackbody radiation with his quantum hypothesis, which states that the energy of a thermal oscillator, Eosc, is not continuous, but instead is a discrete quantity given by the equation: Eosc = nhf n = 1, 2, 3,... where f is the frequency and h is a constant now known as Planck’s constant. Albert Einstein extended the idea by adding that all emitted radiation is quantized. He suggested that light is composed of discrete quanta, rather than of waves. According to his theory, each particle of light, known as a photon, has an energy E given by: E = hf Einstein’s theory helped him explain a phenomenon known as the photoelectric effect, in which a photon of light strikes a photosensitive material and causes an electron to be ejected from the material. A photocell constructed from photosensitive material can produce an electrical current when light shines on it. The kinetic energy, K, of a photoelectron displaced by a photon of energy, hf, is given by: K = hf - φ where the work function, φ, is the minimum energy needed to free the electron from the photosensitive material. No photoemission occurs if the frequency of the incident light falls below a certain cutoff frequency – or threshold frequency – given by: φ f0 = h Einstein's theory explained several aspects of the photoelectric effect that could not be explained by classical theory: • The kinetic energy of photoelectrons is dependent on the light’s frequency. • No photoemission occurs for light below a certain threshold frequency. -

2005 CERN–CLAF School of High-Energy Physics

CERN–2006–015 19 December 2006 ORGANISATION EUROPÉENNE POUR LA RECHERCHE NUCLÉAIRE CERN EUROPEAN ORGANIZATION FOR NUCLEAR RESEARCH 2005 CERN–CLAF School of High-Energy Physics Malargüe, Argentina 27 February–12 March 2005 Proceedings Editors: N. Ellis M.T. Dova GENEVA 2006 CERN–290 copies printed–December 2006 Abstract The CERN–CLAF School of High-Energy Physics is intended to give young physicists an introduction to the theoretical aspects of recent advances in elementary particle physics. These proceedings contain lectures on field theory and the Standard Model, quantum chromodynamics, CP violation and flavour physics, as well as reports on cosmic rays, the Pierre Auger Project, instrumentation, and trigger and data-acquisition systems. iii Preface The third in the new series of Latin American Schools of High-Energy Physics took place in Malargüe, lo- cated in the south-east of the Province of Mendoza in Argentina, from 27 February to 12 March 2005. It was organized jointly by CERN and CLAF (Centro Latino Americano de Física), and with the strong support of CONICET (Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas). Fifty-four students coming from eleven different countries attended the School. While most of the students stayed in Hotel Rio Grande, a few students and the Staff stayed at Microtel situated close by. However, all the participants ate their meals to- gether at Hotel Rio Grande. According to the tradition of the School the students shared twin rooms mixing nationalities and in particular Europeans together with Latin Americans. María Teresa Dova from La Plata University was the local director for the School. -

Real Time Density Functional Simulations of Quantum Scale

Real Time Density Functional Simulations of Quantum Scale Conductance by Jeremy Scott Evans B.A., Franklin & Marshall College (2003) Submitted to the Department of Chemistry in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2009 c Massachusetts Institute of Technology 2009. All rights reserved. Author............................................... ............... Department of Chemistry February 2, 2009 Certified by........................................... ............... Troy Van Voorhis Associate Professor of Chemistry Thesis Supervisor Accepted by........................................... .............. Robert W. Field Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Theses This doctoral thesis has been examined by a Committee of the Depart- ment of Chemistry as follows: Professor Robert J. Silbey.............................. ............. Chairman, Thesis Committee Class of 1942 Professor of Chemistry Professor Troy Van Voorhis............................... ........... Thesis Supervisor Associate Professor of Chemistry Professor Jianshu Cao................................. .............. Member, Thesis Committee Associate Professor of Chemistry 2 Real Time Density Functional Simulations of Quantum Scale Conductance by Jeremy Scott Evans Submitted to the Department of Chemistry on February 2, 2009, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Abstract We study electronic conductance through single molecules by subjecting -

VC 1978 1 5.Pdf

Under Contract with the U.S. Department of Energy Vol. No. 1 January 5, 1978 CHRISTMAS BIRD COUNT RESULTS About 9,150 birds of 60 species were spotted in the second annual Fermilab Christmas bird count. The count was conducted Saturday, Dec. 17, by the DuPage Audubon Society. Held in con junction with the national Audubon Society's 78th annual census nationwide, the local tally enlisted 43 volunteer observers, including two Fermilab people. They were: David Carey, Com- puting Department and Hannu Miettinen, Theory . b' d ... Ferm~ ~r -counters were L-R: J. Kumb, Department. R. Johnson, R. Hoger, D. Carey, B. Foster ... Starting at 4 a.m., observers logged 78 hours of bird-counting time. The birders were divided into 11 parties of 4 to 6 persons each; five persons monitored bird feeders during the count. Fermilab was the focal point of the count area: a circle with a radius of seven and one-half miles as far north as Wayne; south to Aurora; east to Winfield; and west to the Fox River Valley. Party-hours comprised 54 on foot, 24 by car and 22 at feeders. Of 425.5 party-miles covered, 367 were by auto and 58.5 on foot. Richard Hoger, staff assistant in the supply division at Argonne National Laboratory, coordinated the count activities. Paul Mooring was the compiler. The Fermilab area was among five Chicago areas where counts were made, Mooring said. Nationally, counters were at work from Dec. 17 to Jan. 2 on one-day counts. Observers were assigned to eight sub-areas in the Laboratory count circle. -

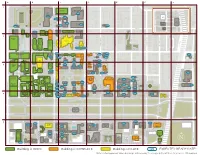

Building Is OPEN Building Is COMPLETE Building Is IN-USE

A B C D E F G E 55TH ST E 55TH ST 1 Campus North Parking Campus North Residential Commons E 52ND ST The Frank and Laura Baker Dining Commons Ratner Stagg Field Athletics Center 5501-25 Ellis Offices - TBD - - TBD - Park Lake S AUG 15 S HARPER AVE Court Cochrane-Woods AUG 15 Art Center Theatre AVE S BLACKSTONE Harper 1452 E. 53rd Court AUG 15 Henry Crown Polsky Ex. Smart Field House - TBD - Alumni Stagg Field Young AUG 15 Museum House - TBD - AUG 15 Building Memorial E 53RD ST E 56TH ST E 56TH ST 1463 E. 53rd Polsky Ex. 5601 S. High Bay West Campus Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Cottage (2021) Utility Plant AUG 15 Michelson High (West) Energy (Central) (East) 55th, 56th, 57th St Grove Center for Metra Station Physics Physics Child Development TAAC 2 Center - Drexel Accelerator Building Medical Campus Parking B Knapp Knapp Medical Regenstein Library Center for Research William Eckhardt Biomedical Building AVE S KENWOOD Donnelley Research Mansueto Discovery Library Bartlett BSLC Center Commons S Lake Park S MARYLAND AVE S MARYLAND S DREXEL BLVD AVE S DORCHESTER AVE S BLACKSTONE S KIMBARK AVE S UNIVERSITY AVE AVE S WOODLAWN S ELLIS AVE Bixler Park Pritzker Need two weeks to transition School of Biopsychological Medicine Research Building E 57TH ST E 57TH ST - TBD - Rohr Chabad Neubauer Collegium- TBD - Center for Care and Discovery Gordon Center for Kersten Anatomy Center - TBD - Integrative Science Physics Hitchcock Hall Cobb Zoology Hutchinson Quadrangle - TBD - Gate Club Institute of- PoliticsTBD - Snell -

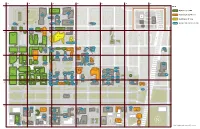

KEY KEY Last Updated: June 15, 2020

Friend Family Health Center Ronald McDonald House A B C D E F G E 55TH ST E 55TH ST KEY 1 Campus North Parking Campus North Residential Commons E 52ND ST The Frank and Laura Baker Dining Commons Building is OPEN Ratner Stagg Field Athletics Center 5501-25 Ellis Offices - TBD - - TBD - Park Lake S Building is COMPLETE AUG 15 S HARPER AVE Court Cochrane-Woods AUG 15 Art Center Theatre AVE S BLACKSTONE Building is IN-USE Harper 1452 E. 53rd Court AUG 15 Henry Crown Polsky Ex. Smart Field House - TBD - Alumni Stagg Field Young AUG 15 Museum House - TBD - DATE EXPECTED READY DATE AUG 15 Building Memorial E 53RD ST E 56TH ST E 56TH ST 1463 E. 53rd Polsky Ex. 5601 S. High Bay West Campus Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Max Palevsky Commons Cottage (2021) Utility Plant AUG 15 Michelson High (West) Energy (Central) (East) 55th, 56th, 57th St Grove Center for Metra Station Physics Physics Child Development TAAC 2 Center - Drexel Accelerator Building Medical Campus Parking B Knapp Knapp Medical Regenstein Library Center for Research William Eckhardt Biomedical Building AVE S KENWOOD Donnelley Research Mansueto Discovery Library Bartlett BSLC Center Commons S Lake Park S KIMBARK AVE S MARYLAND AVE S MARYLAND S DREXEL BLVD AVE S DORCHESTER AVE S BLACKSTONE S UNIVERSITY AVE AVE S WOODLAWN S ELLIS AVE Bixler Park Pritzker Need two weeks to transition School of Biopsychological Medicine Research Building E 57TH ST E 57TH ST - TBD - Rohr Chabad Neubauer CollegiumJUNE 19 Center for Care and Discovery Gordon Center for Kersten Anatomy Center - -

0045-Flyer-Einstein-En-2.Pdf

FEATHERBEDDINGCOMPANYWEIN HOFJEREMIAHSTATUESYN AGOGEDREYFUSSMOOSCEMETERY MÜNSTERPLATZRELATIVI TYE=MC 2NOBELPRIZEHOMELAND PERSECUTIONAFFIDAVIT OFSUPPORTEMIGRATIONEINSTEIN STRASSELETTERSHOLOCAUSTRESCUE FAMILYGRANDMOTHERGRANDFAT HERBUCHAUPRINCETONBAHNHOF STRASSE20VOLKSHOCHSCHULEFOU NTAINGENIUSHUMANIST 01 Albert Einstein 6 7 Albert Einstein. More than just a name. Physicist. Genius. Science pop star. Philosopher and humanist. Thinker and guru. On a par with Copernicus, Galileo or Newton. And: Albert Einstein – from Ulm! The most famous scientist of our time was actually born on 14th March 1879 at Bahnhofstraße 20 in Ulm. Albert Einstein only lived in the city on the Danube for 15 months. His extended family – 18 of Einstein’s cousins lived in Ulm at one time or another – were a respected and deep-rooted part of the city’s society, however. This may explain Einstein’s enduring connection to the city of his birth, which he described as follows in a letter to the Ulmer Abend- post on 18th March 1929, shortly after his 50th birthday: “The birthplace is as much a unique part of your life as the ancestry of your biological mother. We owe part of our very being to our city of birth. So I look on Ulm with gratitude, as it combines noble artistic tradition with simple and healthy character.” 8 9 The “miracle year” 1905 – Einstein becomes the founder of the modern scientific world view Was Einstein a “physicist of the century”? There‘s no doubt of that. In his “miracle year” (annus mirabilis) of 1905 he pub- lished 4 groundbreaking works along- side his dissertation. Each of these was worthy of a Nobel Prize and turned him into a physicist of international standing: the theory of special relativity, the light quanta hypothesis (“photoelectric effect”), Thus, Albert Einstein became the found- for which he received the Nobel Prize in er of the modern scientific world view. -

A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO PUBLIC CATHOLICISM AND RELIGIOUS PLURALISM IN AMERICA: THE ADAPTATION OF A RELIGIOUS CULTURE TO THE CIRCUMSTANCE OF DIVERSITY, AND ITS IMPLICATIONS A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology by Michael J. Agliardo, SJ Committee in charge: Professor Richard Madsen, Chair Professor John H. Evans Professor David Pellow Professor Joel Robbins Professor Gershon Shafir 2008 Copyright Michael J. Agliardo, SJ, 2008 All rights reserved. The Dissertation of Michael Joseph Agliardo is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Chair University of California, San Diego 2008 iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Signature Page ......................................................................................................................... iii Table of Contents......................................................................................................................iv List Abbreviations and Acronyms ............................................................................................vi List of Graphs ......................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................. viii Vita.............................................................................................................................................x -

Spring 2014 Fine Letters

Spring 2014 Issue 3 Department of Mathematics Department of Mathematics Princeton University Fine Hall, Washington Rd. Princeton, NJ 08544 Department Chair’s letter The department is continuing its period of Assistant to the Chair and to the Depart- transition and renewal. Although long- ment Manager, and Will Crow as Faculty The Wolf time faculty members John Conway and Assistant. The uniform opinion of the Ed Nelson became emeriti last July, we faculty and staff is that we made great Prize for look forward to many years of Ed being choices. Peter amongst us and for John continuing to hold Among major faculty honors Alice Chang Sarnak court in his “office” in the nook across from became a member of the Academia Sinica, Professor Peter Sarnak will be awarded this the common room. We are extremely Elliott Lieb became a Foreign Member of year’s Wolf Prize in Mathematics. delighted that Fernando Coda Marques and the Royal Society, John Mather won the The prize is awarded annually by the Wolf Assaf Naor (last Fall’s Minerva Lecturer) Brouwer Prize, Sophie Morel won the in- Foundation in the fields of agriculture, will be joining us as full professors in augural AWM-Microsoft Research prize in chemistry, mathematics, medicine, physics, Alumni , faculty, students, friends, connect with us, write to us at September. Algebra and Number Theory, Peter Sarnak and the arts. The award will be presented Our finishing graduate students did very won the Wolf Prize, and Yasha Sinai the by Israeli President Shimon Peres on June [email protected] well on the job market with four win- Abel Prize. -

Arthur Holly Compton

Arthur Holly Compton ALSO LISTED IN Physicists ALSO KNOWN AS Arthur Holly Compton FAMOUS AS Nobel Prize Laureate in Physics NATIONALITY American Famous American Men RELIGION Baptist BORN ON 10 September 1892 AD Famous 10th September Birthdays ZODIAC SIGN Virgo Virgo Men BORN IN Wooster, Ohio, USA DIED ON 15 March 1962 AD PLACE OF DEATH Berkeley, California, USA FATHER Elias Compton MOTHER Otelia Catherine SIBLINGS Karl Taylor Compton, Wilson Martindale Compton SPOUSE: Betty Charity McCloskey CHILDREN Arthur Allen Compton, John Joseph Compton EDUCATION University of Cambridge, The College of Wooster, Princeton University DISCOVERIES / INVENTIONS Compton Effect AWARDS: Nobel Prize for Physics (1927) Matteucci Medal (1930) Franklin Medal (1940) Hughes Medal (1940) Arthur Holly Compton was a renowned American physicist who first rose to fame with his famous revolutionary discovery of the Compton Effect for which he also won the Nobel Prize in Physics. This discovery confirmed the dual nature of electromagnetic radiation as both a wave and a particle. Thomson was initially interested in astronomy before he shifted his focus to the study of quantum physics. He started his research in Cavendish Laboratory of Cambridge University and this research led to the discovery of Compton Effect. Later on, during the Second World War, Compton became head of the Manhattan Project’s Metallurgical Laboratory. Manhattan Project developed the first nuclear weapons of the world and Compton played a key role in it. He also served as Chancellor of Washington University in St. Louis. Under his leadership, the University made remarkable academic progress; the university formally desegregated its undergraduate divisions, named its first female full professor, and enrolled a record number of students.