Hamlet in (And Off) Stages: Television, Serialization, and Shakespeare in Sons of Anarchy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View in Order to Answer Fortinbras’S Questions

SHAKESPEAREAN VARIATIONS: A CASE STUDY OF HAMLET, PRINCE OF DENMARK Steven Barrie A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS August 2009 Committee: Dr. Stephannie S. Gearhart, Advisor Dr. Kimberly Coates ii ABSTRACT Dr. Stephannie S. Gearhart, Advisor In this thesis, I examine six adaptations of the narrative known primarily through William Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark to answer how so many versions of the same story can successfully exist at the same time. I use a homology proposed by Gary Bortolotti and Linda Hutcheon that explains there is a similar process behind cultural and biological adaptation. Drawing from the connection between literary adaptations and evolution developed by Bortolotti and Hutcheon, I argue there is also a connection between variation among literary adaptations of the same story and variation among species of the same organism. I determine that multiple adaptations of the same story can productively coexist during the same cultural moment if they vary enough to lessen the competition between them for an audience. iii For Pam. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my advisor, Stephannie Gearhart, for being a patient listener when I came to her with hints of ideas for my thesis and, especially, for staying with me when I didn’t use half of them. Her guidance and advice have been absolutely essential to this project. I would also like to thank Kim Coates for her helpful feedback. She has made me much more aware of the clarity of my sentences than I ever thought possible. -

The Tragedy of Hamlet

THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET THE WORKS OF SHAKESPEARE THE TRAGEDY OF HAMLET EDITED BY EDWARD DOWDEN n METHUEN AND CO. 36 ESSEX STREET: STRAND LONDON 1899 9 5 7 7 95 —— CONTENTS PAGE Introduction ix The Tragedy of Hamlet i Appendix I. The "Travelling" of the Players. 229 Appendix II.— Some Passages from the Quarto of 1603 231 Appendix III. Addenda 235 INTRODUCTION This edition of Hamlet aims in the first place at giving a trustworthy text. Secondly, it attempts to exhibit the variations from that text which are found in the primary sources—the Quarto of 1604 and the Folio of 1623 — in so far as those variations are of importance towards the ascertainment of the text. Every variation is not recorded, but I have chosen to err on the side of excess rather than on that of defect. Readings from the Quarto of 1603 are occa- sionally given, and also from the later Quartos and Folios, but to record such readings is not a part of the design of this edition. 1 The letter Q means Quarto 604 ; F means Folio 1623. The dates of the later Quartos are as follows: —Q 3, 1605 161 1 undated 6, For ; Q 4, ; Q 5, ; Q 1637. my few references to these later Quartos I have trusted the Cambridge Shakespeare and Furness's edition of Hamlet. Thirdly, it gives explanatory notes. Here it is inevitable that my task should in the main be that of selection and condensation. But, gleaning after the gleaners, I have perhaps brought together a slender sheaf. -

PADRAIC Mckinley Editor

PADRAIC McKINLEY Editor FEATURES DIRECTORS PRODUCERS/STUDIOS BOSS LEVEL Joe Carnahan Scott Putman, Frank Grillo Emmett/Furla/Oasis Films WHEELMAN Jeremy Rush George Parra, Frank Grillo / Netflix PRIDE AND PREJUDICE Burr Steers Sue Baden-Powell, Marc Butan, Lauren Selig AND ZOMBIES Allison Shearmur / Lionsgate WILD CARD Simon West Steve Chasman, Brian Pitt, Jib Polhemus Recut Jason Statham / Lionsgate HOMEFRONT Gary Fleder Avi Lerner, John Thompson Open Road Films / Millennium CHARLIE ST. CLOUD Burr Steers Michael Fottrell, Marc Platt Universal Pictures 17 AGAIN Burr Steers Jennifer Gibgot, Adam Shankman Dara Weintraub / New Line Cinema THE EXPRESS Gary Fleder Derek Dauchy, John Davis, Arne Schmidt Davis Entertainment / Universal Pictures ALFIE Charles Shyer Sean Daniel, Diana Phillips, Elaine Pope Paramount Pictures IF ONLY Gil Junger Basil Iwanyk, Jeffrey Silver, Scott Strauss Tapestry Films / Sony IGBY GOES DOWN Burr Steers Lisa Tornell, David Rubin, Marco Weber MGM TELEVISION AMERICAN GODS Season 2 Various Directors Jesse Alexander, Reid Shane Editor, Executive Producer Dante DiLoreto / Fremantle Media / Starz FIGHT WORLD Docu-Series Padraic McKinley Todd Lubin, John Gerstel / Matador / Netflix Editor, Director KINGDOM Pilot & Series Various Directors Byron Balasco, Adam Davidson Supervising Editor, Producer, Director Endemol USA / DirecTV ANIMAL KINGDOM Christopher Chulack Terri Murphy, Lou Wells One Episode Warner Bros. / TNT BEAUTY AND THE BEAST Pilot Gary Fleder Sherri Cooper, Jennifer Levin, Tony Thomas Paul Junger Witt / CBS -

2017 Information & Record Book

2017 INFORMATION & RECORD BOOK OWNERSHIP OF THE CLEVELAND INDIANS Paul J. Dolan John Sherman Owner/Chairman/Chief Executive Of¿ cer Vice Chairman The Dolan family's ownership of the Cleveland Indians enters its 18th season in 2017, while John Sherman was announced as Vice Chairman and minority ownership partner of the Paul Dolan begins his ¿ fth campaign as the primary control person of the franchise after Cleveland Indians on August 19, 2016. being formally approved by Major League Baseball on Jan. 10, 2013. Paul continues to A long-time entrepreneur and philanthropist, Sherman has been responsible for establishing serve as Chairman and Chief Executive Of¿ cer of the Indians, roles that he accepted prior two successful businesses in Kansas City, Missouri and has provided extensive charitable to the 2011 season. He began as Vice President, General Counsel of the Indians upon support throughout surrounding communities. joining the organization in 2000 and later served as the club's President from 2004-10. His ¿ rst startup, LPG Services Group, grew rapidly and merged with Dynegy (NYSE:DYN) Paul was born and raised in nearby Chardon, Ohio where he attended high school at in 1996. Sherman later founded Inergy L.P., which went public in 2001. He led Inergy Gilmour Academy in Gates Mills. He graduated with a B.A. degree from St. Lawrence through a period of tremendous growth, merging it with Crestwood Holdings in 2013, University in 1980 and received his Juris Doctorate from the University of Notre Dame’s and continues to serve on the board of [now] Crestwood Equity Partners (NYSE:CEQP). -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

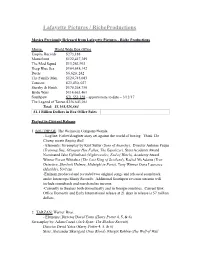

Riche Productions Current Slate

Lafayette Pictures / RicheProductions Movies Previously Released from Lafayette Pictures - Riche Productions Movie World Wide Box Office Empire Records $273,188 Mousehunt $122,417,389 The Mod Squad $13,263,993 Deep Blue Sea $164,648,142 Duets $6,620, 242 The Family Man $124,745,083 Tomcats $23,430, 027 Starsky & Hutch $170,268,750 Bride Wars $114,663,461 Southpaw $71,553,328 - approximate to date – 3/12/17 The Legend of Tarzan $356,643,061 Total: $1,168,526,664 $1.1 Billion Dollars in Box Office Sales Project in Current Release: 1. SOUTHPAW: The Weinstein Company/Wanda - Logline: Father/daughter story set against the world of boxing. Think The Champ meets Raging Bull. - Elements: Screenplay by Kurt Sutter (Sons of Anarchy). Director Antoine Fuqua (Training Day, Olympus Has Fallen, The Equalizer), Stars Academy Award Nominated Jake Gyllenhaal (Nightcrawler, End of Watch), Academy Award Winner Forest Whitaker (The Last King of Scotland), Rachel McAdams (True Detective, Sherlock Holmes, Midnight in Paris), Tony Winner Oona Laurence (Matilda), 50 Cent. -Eminem produced and recorded two original songs and released soundtrack under Interscope/Shady Records. Additional Southpaw revenue streams will include soundtrack and merchandise income. -Currently in theaters both domestically and in foreign countries. Current Box Office Domestic and Early International release at 21 days in release is 57 million dollars. 2. TARZAN: Warner Bros. - Elements: Director David Yates (Harry Potter 4, 5, & 6) Screenplay by: Adam Cozad (Jack Ryan: The Shadow Recruit). Director David Yates (Harry Potter 4, 5, & 6) Stars: Alexander Skarsgard (True Blood), Margot Robbie (The Wolf of Wall Street), Academy Award Nominated Samuel L. -

Revising the Western: Connecting Genre Rituals and American

CSCXXX10.1177/1532708614527561Cultural Studies <span class="symbol" cstyle="symbol">↔</span> Critical MethodologiesCastleberry 527561research-article2014 Article Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies 2014, Vol. 14(3) 269 –278 Revising the Western: Connecting © 2014 SAGE Publications Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav Genre Rituals and American Western DOI: 10.1177/1532708614527561 Revisionism in TV’s Sons of Anarchy csc.sagepub.com Garret L. Castleberry1 Abstract In this article, I analyze the TV show Sons of Anarchy (SOA) and how the cable drama revisits and revises the American Western film genre. I survey ideological contexts and tropes that span Western mythologies like landscape and mise-en- scene to struggles for family, community, and the continuation of Native American plight. I trace connections between the show’s fictitious town setting and how the narrative inverts traditional community archetypes to reinsert a new outlaw status quo. I inspect the role of border reversal, from open expansion in Westerns to the closed-door post-globalist world of SAMCRO. I quickdraw from a number of film theory scholars as I trick shoot their critiques of Western cinema against the updated target of SOA’s fictitious Charming, CA. I reckon that this revised update of outlaw culture, gunslinger violence, and the drama’s subsequent popularity communicates a post-9/11 trauma playing out on television. Through the sage wisdom of autoethnography, I recall personal memories as an ideological travelogue for navigating the rhetoric power this drama ignites. As with postwar movements of biker history that follow World War II and Vietnam, SOA races against Western form while staying distinctly faithful. -

The Work of the Critic

CHAPTER 1 The Work of the Critic Oh, gentle lady, do not put me to’t. For I am nothing if not critical. —Iago to Desdemona (Shakespeare, Othello, Act 2, Scene I) INTRODUCTION What is the advantage of knowing how to perform television criticism if you are not going to be a professional television critic? The advantage to you as a television viewer is that you will not only be able to make informed judgment about the television programs you watch, but also you will better understand your reaction and the reactions of others who share the experience of watching. Critical acuity enables you to move from casual enjoyment of a television program to a fuller and richer understanding. A viewer who does not possess critical viewing skills may enjoy watching a television program and experience various responses to it, such as laughter, relief, fright, shock, tension, or relaxation. These are fun- damental sensations that people may get from watching television, and, for the most part, viewers who are not critics remain at this level. Critical awareness, however, enables you to move to a higher level that illuminates production practices and enhances your under- standing of culture, human nature, and interpretation. Students studying television production with ambitions to write, direct, edit, produce, and/or become camera operators will find knowledge of television criticism necessary and useful as well. Television criticism is about the evaluation of content, its context, organiza- tion, story and characterization, style, genre, and audience desire. Knowledge of these concepts is the foundation of successful production. THE ENDS OF CRITICISM Just as critics of books evaluate works of fiction and nonfiction by holding them to estab- lished standards, television critics utilize methodology and theory to comprehend, analyze, interpret, and evaluate television programs. -

Hamlet on the Screen Prof

Scholars International Journal of Linguistics and Literature Abbreviated Key Title: Sch Int J Linguist Lit ISSN 2616-8677 (Print) |ISSN 2617-3468 (Online) Scholars Middle East Publishers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates Journal homepage: https://saudijournals.com/sijll Review Article Hamlet on the Screen Prof. Essam Fattouh* English Department, Faculty of Arts, University of Alexandria (Egypt) DOI: 10.36348/sijll.2020.v03i04.001 | Received: 20.03.2020 | Accepted: 27.03.2020 | Published: 07.04.2020 *Corresponding author: Prof. Essam Fattouh Abstract The challenge of adapting William Shakespeare‟s Hamlet for the screen has preoccupied cinema from its earliest days. After a survey of the silent Hamlet productions, the paper critically examines Asta Nielsen‟s Hamlet: The Drama of Vengeance by noting how her main character is really a woman. My discussion of the modern productions of Shakespeare begins with a critical discussion of Lawrence Olivier‟s seminal production of 1948. The Russian Hamlet of 1964, directed by Grigori Kozintsev, is shown to combine a psychological interpretation of the hero without disregarding its socio-political context. The action-film genre deployed by Franco Zeffirelli in his 1990 adaptation of the play, through a moving performance by Mel Gibson, is analysed. Kenneth Branagh‟s ambitious and well-financed production of 1996 is shown to be somewhat marred by its excesses. Michael Almereyda‟s attempt to present Shakespeare‟s hero in a contemporary setting is shown to have powerful moments despite its flaws. The paper concludes that Shakespeare‟s masterpiece will continue to fascinate future generations of directors, actors and audiences. Keywords: Shakespeare – Hamlet – silent film – film adaptations – modern productions – Russian – Olivier – Branagh – contemporary setting. -

“I Will Never Play the Dane”: Shakespeare and the Performer's Failure

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by MURAL - Maynooth University Research Archive Library DOI: 10.1111/lic3.12470 ARTICLE “I will never play the Dane”: Shakespeare and the performer's failure Richard O'Brien University of Birmingham Abstract Correspondence Richard O'Brien, Department of Film and The cultural prestige accorded to Shakespeare's great roles Creative Writing, University of Birmingham, has made them high watermarks for ‘great acting’ in general. Birmingham, UK. Email: [email protected] They are therefore also uniquely capable of channelling a performer's sense of his own failure. The 1987 film Withnail &Ifamously ends with its title character, an out‐of‐work actor and self‐destructive alcoholic, delivering Hamlet's “What a piece of work is a man” to an audience of unre- sponsive wolves. And in 2014's The Trip to Italy, Steve Coogan plays a fictionalised version of himself: a comedian who fears he will never be remembered as a serious artist. On a visit to Pompeii, Coogan's delivery of Hamlet's speech to Yorick's skull similarly becomes a way of channelling the series's wider reflections on fame, mortality, and the value of the actor's art. Drawing on Marvin Carlson's argument that the role of Hamlet is unusually densely ghosted by its previous occupants, this article will explore how these two contemporary depictions of struggling performers evoke the received idea of the great Shakespearean role as the pinnacle of the actor's art to respond to the dilemma of how to cope with creative failure. -

Writing the Shakespeare Mask: the Novelist's Choices

Writing The Shakespeare Mask: The Novelist’s Choices Newton Frohlich *Corresponding Author: [email protected] Copyright©2016 by authors, all rights reserved. Authors agree that this article remains permanently open access under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License 4.0 International License Abstract The authorship of the works of Shakespeare by de Vere is depicted from when he was five to the time of his the glover from Stratford -on-Avon has been considered a tragic death, including his "favored," sexual relationship myth almost from its inception. No less than Charles Dickins, with the queen and his intimate relationship with Emilia Mark Twain, Henry and William James, Ralph Waldo Bassano, who is widely accepted as the "Dark Lady" of Emerson, Herman Melville, Walt Whitman, Royal Shake-speare's Sonnets. (There is no evidence of any Shakespeare Company actors John Gielgud, Derek Jacobi, relationship between the Stratford man and Emilia Bassano.) Jeremy Irons, and Michael York, British Prime Minister In short, while the documentary evidence of de Vere's -- or Benjamin Disraeli, five United States Supreme Court the Stratford man's -- authorship of the works of Shakespeare Justices, and thousands who signed a Declaration of Doubt is missing, the circumstantial evidence of de Vere's About Will circulating the World-Wide Web have attested to authorship is overwhelming. And as United States Supreme their doubts. In response to the request by his publisher, Court Justice John Paul Stevens puts it, "circumstantial author Newton Frohlich, commencing research connected evidence can be as persuasive as documentary evidence with a sequel to his novel about Columbus, came across especially where, as here, there's so much of it. -

Amleth, Prince of Denmark

Amleth, Prince of Denmark Saxo Grammaticus Amleth, Prince of Denmark Table of Contents Amleth, Prince of Denmark From the Gesta Danorum of Saxo Grammaticus..................................................1 translated by Oliver Elton..............................................................................................................................1 i Amleth, Prince of Denmark From the Gesta Danorum of Saxo Grammaticus translated by Oliver Elton Horwendil, King of Denmark, married Gurutha, the daughter of Rorik, and she bore him a son, whom they named Amleth. Horwendil's good fortune stung his brother Feng with jealousy, so that the latter resolved treacherously to waylay his brother, thus showing that goodness is not safe even from those of a man's own house. And behold when a chance came to murder him, his bloody hand sated the deadly passion of his soul. Then he took the wife of the brother he had butchered, capping unnatural murder with incest. For whoso yields to one iniquity, speedily falls an easier victim to the next, the first being an incentive to the second. Also the man veiled the monstrosity of his deed with such hardihood of cunning, that he made up a mock pretense of goodwill to excuse his crime, and glossed over fratricide with a show of righteousness. Gerutha, said he, though so gentle that she would do no man the slightest hurt, had been visited with her husband's extremest hate; and it was all to save her that he had slain his brother; for he thought it shameful that a lady so meek and unrancorous should suffer the heavy disdain of he husband. Nor did his smooth words fail in their intent; for at courts, where fools are sometimes favored and backbiters preferred, a lie lacks not credit.