Welcome to the Fort Tryon Jewish Center! an Independent, Traditional, Egalitarian Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RCVP: Really Cool

1 RCVP: Really Cool and Valuable Person Compiled by Taylor-Paige Guba, RCVP of NFTY Ohio Valley 2016-2017 with help from past RCVPs and NFTY resources Contact info and Social Media Phone: 317-902-8934 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @ov_rcvp Instagram: @gubagirl Facebook: Taylor-Paige Guba Don’t forget to follow NFTY-OV on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram! Join the NFTY-OV Facebook group! 2 And now a rap from DJ goobz… So listen up peeps. I got a couple things I need you to hear, You better be listening with two ears, The path you are walking down today, Is a dope path so make some way, First you got the R and that’s pretty sweet, Religion is tight so be ready to yeet, The C comes next just creepin on in, Culture is swag so let’s begin, The VP part brings it all together, Wrap it all up and you got 4 letters, Word to yo mamma To clarify, I am very excited to work with all of you fabulous people. Our network has complex responsibilities and I have put everything I could think of that would help us all have a great year in this network packet. Here you will find: ● Some basic definitions ● Standard service outlines ● Jewish holiday dates ● A few other fun items 3 So What Even is Reform Judaism? Great question! It is a pluralistic, progressive, egalitarian sect of Judaism that allows the individual autonomy to decide their personal practices and observations based on all Jewish teachings (Torah, Talmud, Halacha, Rabbis etc.) as well as morals, ethics, reason and logic. -

The Psalms in Our Times: an Online Study of the Psalms During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The Psalms in Our Times: An Online Study of the Psalms During the COVID-19 Pandemic Agenda for Weeks 1-3: - Series overview (week 1 only) - Check-in and review - Introduction of the Week’s Psalm(s) - Discussion and Question & Answer Agenda for Week 4: - Check-in and review - Sharing of Psalms (optional) - Wrap-up Sources for Psalm texts: - Book of Common Prayer (Psalter, pages 582-808) - Oremus Bible Browser (bible.oremus.org) Participants are invited to this document and take notes (or not) and work on creating their own Psalm for Session 4 (or not). All videos will be posted to the “St. John’s Episcopal Church Lancaster” YouTube page so participants can review or catch up as needed. Session 1 Psalm 29 Psalm 146 1Ascribe to the Lord, O heavenly beings, 1Praise the Lord! Praise the Lord, O my ascribe to the Lord glory and strength. soul! 2Ascribe to the Lord the glory of his name; 2I will praise the Lord as long as I live; I will worship the Lord in holy splendor. sing praises to my God all my life long. 3The voice of the Lord is over the waters; 3Do not put your trust in princes, in the God of glory thunders, the Lord, over mortals, in whom there is no help. mighty waters. 4When their breath departs, they return to 4The voice of the Lord is powerful; the voice the earth; on that very day their plans of the Lord is full of majesty. perish. 5The voice of the Lord breaks the cedars; 5Happy are those whose help is the God of the Lord breaks the cedars of Lebanon. -

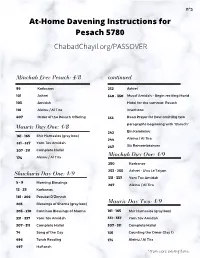

Copy of Copy of Prayers for Pesach Quarantine

ב"ה At-Home Davening Instructions for Pesach 5780 ChabadChayil.org/PASSOVER Minchah Erev Pesach: 4/8 continued 99 Korbanos 232 Ashrei 101 Ashrei 340 - 350 Musaf Amidah - Begin reciting Morid 103 Amidah Hatol for the summer, Pesach 116 Aleinu / Al Tira insertions 407 Order of the Pesach Offering 353 Read Prayer for Dew omitting two paragraphs beginning with "Baruch" Maariv Day One: 4/8 242 Ein Kelokeinu 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 244 Aleinu / Al Tira 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 247 Six Remembrances 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 174 Aleinu / Al Tira Minchah Day One: 4/9 250 Korbanos 253 - 255 Ashrei - U'va Le'Tziyon Shacharis Day One: 4/9 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 267 Aleinu / Al Tira 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) Maariv Day Two: 4/9 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 74 Song of the Day 136 Counting the Omer (Day 1) 496 Torah Reading 174 Aleinu / Al Tira 497 Haftorah *From a pre-existing flame Shacharis Day Two: 4/10 Shacharis Day Three: 4/11 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 12 - 25 Korbanos 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) 203 - 210 Blessings of Shema & Shema 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 211- 217 Shabbos Amidah - add gray box 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah pg 214 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 "Half" Hallel - Omit 2 indicated 74 Song of -

Ruach Congregation Beth Shalom

6800 35th Ave NE Ruach Seattle, WA 98115 Congregation Beth Shalom 206.524.0075 September 2017 • Elul 5777-Tishrei 5778 Volume 50, Issue 1 MESSAGE FROM RABBI BORODIN A Yom Kippur Challenge Amram Gaon, then 22 with Maimonides in the 12th century, to 36 sins in the Machzor Vitry (only slightly later than Judaism is based on a few foundational principles. One of Maimonides), to our 44 line version found in our machzorim these is that there is a difference between right and wrong, today. Its current form is an acrostic, hoping to suggest the and we as humans can learn and discern between them. A extensive breadth in which we have sinned and erred, both second principle is that, as human beings, we are both through omission and commission. This formula is intended imperfect and we can improve and make some correction for to inspire us and assist us on the process of self-reflection past errors. And a third is about the importance of regularly and confession. It is not supposed to be a substitute of our examining our character and admitting our wrongs as part own process and directly asking for forgiveness from the of a program of self-improvement. people we have hurt. This self-reflection exercise is intended to be daily with a I find reciting the al chet prayer powerful - perhaps because more in depth examination connected to the high holidays, of the physical aspect of beating our hearts, and through our and Yom Kippur in particular. To help with this process, communal singing of part of it. -

A Guide to the Shabbat Morning Service at Heska Amuna Synagogue Common Terms and Phrases Adonai (Lit. Sir Or Master) – Word Th

A Guide to the Shabbat Morning Service at Heska Amuna Synagogue Common Terms and Phrases Adonai (lit. sir or master) – word that is substituted for the holiest of God’s personal names, YHVH, in Hebrew prayer. The prayer book in use at Heska Amuna translates this word as Lord. aliyah (pl. aliyot) – a Torah reading. Also, the honor of reciting the blessings for a Torah reading. The aliyot on Shabbat are: (1) Kohen (3) Shelishi (5) Hamishi (7) Shevi’i (2) Levi (4) Revi’i (6) Shishi (8) Maftir amidah – standing prayer, the central prayer of every service. Aron Kodesh (lit. holy ark) – the cabinet housing the Torah scrolls when not in use. b’racha (pl. b’rachot) – blessing. barukh hu u-varukh sh’mo (lit. praised is He and praised is His name) – the congregational response whenever the prayer leader begins a blessing with barukh attah Adonai (praised are You, Lord). At the end of the blessing, the congregation responds with amen. bimah – the raised platform at the front of the sanctuary where the Ark is located. birchot hashachar – the morning blessings, recited before the start of shacharit. chazarat hashatz (lit. repetition of the shatz) – the loud recitation of the amidah following the silent reading. chumash – the book containing the Torah and Haftarah readings. The chumash used at Heska Amuna is Etz Hayim (lit. tree of life). d’var Torah (lit. word of Torah) – a talk on topics relating to a section of the Torah. 1 gabbai (pl. gabbaim) – Two gabbaim stand at the reader’s table during the Torah reading. -

Psalms of Praise: “Pesukei Dezimra ”

Dr. Yael Ziegler Pardes The Psalms 1 Psalms of Praise: “Pesukei DeZimra” 1) Shabbat 118b אמר רבי יוסי: יהא חלקי מגומרי הלל בכל יום. איני? והאמר מר: הקורא הלל בכל יום - הרי זה מחרף ומגדף! - כי קאמרינן - בפסוקי דזמרא R. Yosi said: May my portion be with those who complete the Hallel every day. Is that so? Did not the master teach: “Whoever recites the Hallel every day, he is blaspheming and scoffing?” [R. Yosi explained:] When I said it, it was regarding Pesukei DeZimra. Rashi Shabbat 118b הרי זה מחרף ומגדף - שנביאים הראשונים תיקנו לומר בפרקים לשבח והודיה, כדאמרינן בערבי פסחים, )קיז, א(, וזה הקוראה תמיד בלא עתה - אינו אלא כמזמר שיר ומתלוצץ. He is blaspheming and scoffing – Because the first prophets establish to say those chapters as praise and thanks… and he who recites it daily not in its proper time is like one who sings a melody playfully. פסוקי דזמרא - שני מזמורים של הילולים הללו את ה' מן השמים הללו אל בקדשו . Pesukei DeZimra – Two Psalms of Praise: “Praise God from the heavens” [Psalm 148]; “Praise God in His holiness” [Psalm 150.] Massechet Soferim 18:1 Dr. Yael Ziegler Pardes The Psalms 2 אבל צריכין לומר אחר יהי כבוד... וששת המזמורים של כל יום; ואמר ר' יוסי יהא חלקי עם המתפללים בכל יום ששת המזמורים הללו 3) Maharsha Shabbat 118b ה"ז מחרף כו'. משום דהלל נתקן בימים מיוחדים על הנס לפרסם כי הקדוש ברוך הוא הוא בעל היכולת לשנות טבע הבריאה ששינה בימים אלו ...ומשני בפסוקי דזמרה כפירש"י ב' מזמורים של הלולים כו' דאינן באים לפרסם נסיו אלא שהם דברי הלול ושבח דבעי בכל יום כדאמרי' לעולם יסדר אדם שבחו של מקום ואח"כ יתפלל וק"ל: He is blaspheming. -

A Guide to Our Shabbat Morning Service

Torah Crown – Kiev – 1809 Courtesy of Temple Beth Sholom Judaica Museum Rabbi Alan B. Lucas Assistant Rabbi Cantor Cecelia Beyer Ofer S. Barnoy Ritual Director Executive Director Rabbi Sidney Solomon Donna Bartolomeo Director of Lifelong Learning Religious School Director Gila Hadani Ward Sharon Solomon Early Childhood Center Camp Director Dir.Helayne Cohen Ginger Bloom a guide to our Endowment Director Museum Curator Bernice Cohen Bat Sheva Slavin shabbat morning service 401 Roslyn Road Roslyn Heights, NY 11577 Phone 516-621-2288 FAX 516- 621- 0417 e-mail – [email protected] www.tbsroslyn.org a member of united synagogue of conservative judaism ברוכים הבאים Welcome welcome to Temple Beth Sholom and our Shabbat And they came, every morning services. The purpose of this pamphlet is to provide those one whose heart was who are not acquainted with our synagogue or with our services with a brief introduction to both. Included in this booklet are a history stirred, and every one of Temple Beth Sholom, a description of the art and symbols in whose spirit was will- our sanctuary, and an explanation of the different sections of our ing; and they brought Saturday morning service. an offering to Adonai. We hope this booklet helps you feel more comfortable during our service, enables you to have a better understanding of the service, and introduces you to the joy of communal worship. While this booklet Exodus 35:21 will attempt to answer some of the most frequently asked questions about the synagogue and service, it cannot possibly anticipate all your questions. Please do not hesitate to approach our clergy or regular worshipers with your questions following our services. -

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim

On the Proper Use of Niggunim for the Tefillot of the Yamim Noraim Cantor Sherwood Goffin Faculty, Belz School of Jewish Music, RIETS, Yeshiva University Cantor, Lincoln Square Synagogue, New York City Song has been the paradigm of Jewish Prayer from time immemorial. The Talmud Brochos 26a, states that “Tefillot kneged tmidim tiknum”, that “prayer was established in place of the sacrifices”. The Mishnah Tamid 7:3 relates that most of the sacrifices, with few exceptions, were accompanied by the music and song of the Leviim.11 It is therefore clear that our custom for the past two millennia was that just as the korbanot of Temple times were conducted with song, tefillah was also conducted with song. This is true in our own day as well. Today this song is expressed with the musical nusach only or, as is the prevalent custom, nusach interspersed with inspiring communally-sung niggunim. It once was true that if you wanted to daven in a shul that sang together, you had to go to your local Young Israel, the movement that first instituted congregational melodies c. 1910-15. Most of the Orthodox congregations of those days – until the late 1960s and mid-70s - eschewed the concept of congregational melodies. In the contemporary synagogue of today, however, the experience of the entire congregation singing an inspiring melody together is standard and expected. Are there guidelines for the proper choice and use of “known” niggunim at various places in the tefillot of the Yamim Noraim? Many are aware that there are specific tefillot that must be sung "...b'niggunim hanehugim......b'niggun yodua um'sukon um'kubal b'chol t'futzos ho'oretz...mimei kedem." – "...with the traditional melodies...the melody that is known, correct and accepted 11 In Arachin 11a there is a dispute as to whether song is m’akeiv a korban, and includes 10 biblical sources for song that is required to accompany the korbanos. -

From Preachingtoday.Com Top 10 Thanksgiving Illustrations Click Here to Subscribe and Get $20 Off!

from preachingtoday.com top 10 Thanksgiving Illustrations Click here to subscribe and get $20 off! References: 1. Praise God with Your 23,000 Breaths per Day Psalm 3:1-4; Psalm 23:1-3; Psalm 27:1-6; Psalm 34:4-6; Psalm 66:1-2; Psalm 86:1-4; Psalm 91:1- 15; Psalm 130:1-2; Psalm 142:1-3; Matthew 7:9-11; Matthew 8:1-2; Luke 18:1-8; Romans 12:12; Illustration: You take approximately 23,000 breaths every day, but when was the last time you Ephesians 6:18; Philippians 4:6-7; Philippians 4:13; Colossians 4:2; 1 Thessalonians 5:16-18. thanked God for one of them? The process of inhaling oxygen and exhaling carbon dioxide is a complicated respiratory task that requires physiological precision. We tend to thank God for the things that take our breath away. And that’s fine. But maybe we should thank him for every other breath too! 3. Grandson Refuses to Express His Thanks Mark Batterson, All In (Zondervan, 2013), page 119 We took our grandson (age 3 at the time) to Chuck E. Cheese’s for pizza and noisy rides. When Related Topics: Adoration; Exaltation of God; God, goodness of; God, greatness of; Gratitude; the evening ended, his grandmother buckled him into his car seat and said, “Now be sure you Ingratitude; Praise; Thanks; Thanksgiving; Thanksgiving Day; Worship say thank you to your Papa.” References: Silence. No reaction. She said again, “Did you hear me? Be sure you say thank you to Papa.” Psalm 98:4; Psalm 100:1-3; Psalm 103:1-3; Psalm 103:22; Psalm 145:1-3; Psalm 146:1-2; Psalm Again, silence. -

Yom Kippur in Shul 5781

Yom Kippur in Shul 5781 Please note that if you will be attending a late Kol Nidre service, that no tallit is worn. We will begin davening in Shul on Yom Kippur morning with Ha-Melekh. You are encouraged to recite Birchot haShachar through the end of Pesukei deZimra at home. We will omit most piyyutim in our tefilot. If we are reciting a piyyut, it will be noted below. Please note that we will not be distributing kibbudim this year. One of the rabbis, gabbaim or officers will handle opening and closing the ark at each minyan. During Musaf, we will only bow once at Aleinu, and not during the rest of the Avodah. Also, Kohanim will leave to wash their own hands prior to Birkat Kohanim, Leviim will remain in Shul. During Birkat Kohanim there will be no singing. General Reminders: - Masks must be worn at all times in the building, covering both your nose and mouth - You must sit in your assigned seating; - To adhere to social distancing rules, please do not walk around in the Shul; - Unfortunately, except for the Chazzan, we will not be singing as a community; - Please do not stand or daven in the aisles; - So that we can start punctually and to minimize crowding at the entrance, please make every effort to arrive on time. - Please remember to bring your own Machzor to shul. If you would like to borrow a Machzor from The Jewish Center prior to Rosh Hashanah, please use this form. https://www.jewishcenter.org/form/Machzor%20Loan%20Program If you have any questions or concerns, or if we can be of assistance to you in any way, please do not hesitate to reach out to us, Rabbi Yosie Levine at [email protected] or Rabbi Elie Buechler at [email protected]. -

Ezrat Avoteinu the Final Tefillah Before Engaging in the Shacharit

Ezrat Avoteinu The Final Tefillah before engaging in the Shacharit Amidah / Silent Meditative Prayer is Ezrat Avoteinu Atoh Hu Meolam – Hashem, You have been the support and salvation for our forefathers since the beginning….. The subject of this Tefillah is Geulah –Redemption, and it concludes with Baruch Atoh Hashem Ga’al Yisrael – Blessed are You Hashem, the Redeemer of Israel. This is in consonance with the Talmudic passage in Brachot 9B that instructs us to juxtapose the blessing of redemption to our silent Amidah i.e. Semichat Geulah LeTefillah. Rav Schwab zt”l in On Prayer pp 393 quotes the Siddur of Rav Pinchas ben R’ Yehudah Palatchik who writes that our Sages modeled our Tefillot in the style of the prayers of our forefathers at the crossing of the Reed Sea. The Israelites praised God in song and in jubilation at the Reed Sea, so too we at our moment of longing for redemption express song, praise and jubilation. Rav Pinchas demonstrates that embedded in this prayer is an abbreviated summary of our entire Shacharit service. Venatenu Yedidim – Our Sages instituted: 1. Zemirot – refers to Pesukei Dezimra 2. Shirot – refers to Az Yashir 3. Vetishbachot – refers to Yishtabach 4. Berachot – refers to Birkas Yotzair Ohr 5. Vehodaot – refers to Ahavah Rabbah 6. Lamelech Kel Chay Vekayam – refers to Shema and the Amidah After studying and analyzing the Shacharit service, we can see a strong and repetitive focus on our Exodus from Egypt. We say Az Yashir, we review the Exodus in Ezrat Avoteinu, in Vayomer, and Emet Veyatziv…. Why is it that we place such a large emphasis on the Exodus each and every day in the morning and the evening? The simple answer is because the genesis of our nation originates at the Exodus from Egypt. -

Walking the High Holy Days Together

September 2020/5781 Edgware & Hendon Reform Synagogue Walking the High Holy Days Together Your guide to what’s on online and in person. Enhancing your at home experience. 118 Stonegrove, Edgware, Middlesex, HA8 8AB Telephone: 020 8238 1000 Email: [email protected] Web: www.ehrs.uk Charity:1172458 Company:10622971 Contents Machzorim and Technology Questions………….. Page 2 Our service Channels explained…………. …….... Page 3 Preparing for the High Holy Days…. ……………. Page 4 Full Rosh Hashanah Schedule ……………… Pages 5-8 A Rosh Hashanah Seder………………………….. Pages 9-12 Rosh Hashanah Torah Readings………………….. Pages 13-16 Tashlich……………………………………………. Pages 17-18 Heshbon HaNefesh - an Inventory for the Soul…. Page 19 EHRS Voices: Connecting to the Liturgy of the High Holy Days…………………………………………... Pages 20-24 RH Family Activities……………………………………. Page 25-26 Full Kol Nidre & Yom Kippur Schedule ……… Pages 27-30 Yom Kippur Resources……………………………… Page 31 Yom Kippur Torah Study…………………………… Pages 32-34 A Closer look at Jonah………………………………. Pages 35-36 After Yom Kippur - Build Your Own Sukkah………. Page 37-38 Sukkot and Simchat Torah schedule………………… Back Page With huge thanks to the EHRS professional and lay teams for all their contributions to this booklet. Particular thanks to our Communications and Marketing Officer Bonnie Lemer, for pulling it all together so beautifully. 1 WhatA is look in this Ahead book? We have included in these pages all you need to know about every one of our services over the course of the High Holy Days, as well as readings, learning, exercises & activities to enhance your experience of the festivals while celebrating at home, online, and we hope for some, in person outdoors.