Sébastien Lefait

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Me and Orson Welles Press Kit Draft

presents ME AND ORSON WELLES Directed by Richard Linklater Based on the novel by Robert Kaplow Starring: Claire Danes, Zac Efron and Christian McKay www.meandorsonwelles.com.au National release date: July 29, 2010 Running time: 114 minutes Rating: PG PUBLICITY: Philippa Harris NIX Co t: 02 9211 6650 m: 0409 901 809 e: [email protected] (See last page for state publicity and materials contacts) Synopsis Based in real theatrical history, ME AND ORSON WELLES is a romantic coming‐of‐age story about teenage student Richard Samuels (ZAC EFRON) who lucks into a role in “Julius Caesar” as it’s being re‐imagined by a brilliant, impetuous young director named Orson Welles (impressive newcomer CHRISTIAN MCKAY) at his newly founded Mercury Theatre in New York City, 1937. The rollercoaster week leading up to opening night has Richard make his Broadway debut, find romance with an ambitious older woman (CLAIRE DANES) and eXperience the dark side of genius after daring to cross the brilliant and charismatic‐but‐ sometimes‐cruel Welles, all‐the‐while miXing with everyone from starlets to stagehands in behind‐the‐scenes adventures bound to change his life. All’s fair in love and theatre. Directed by Richard Linklater, the Oscar Nominated director of BEFORE SUNRISE and THE SCHOOL OF ROCK. PRODUCTION I NFORMATION Zac Efron, Ben Chaplin, Claire Danes, Zoe Kazan, Eddie Marsan, Christian McKay, Kelly Reilly and James Tupper lead a talented ensemble cast of stage and screen actors in the coming‐of‐age romantic drama ME AND ORSON WELLES. Oscar®‐nominated director Richard Linklater (“School of Rock”, “Before Sunset”) is at the helm of the CinemaNX and Detour Filmproduction, filmed in the Isle of Man, at Pinewood Studios, on various London locations and in New York City. -

Orson Welles's Deconstruction of Traditional Historiographies In

“How this World is Given to Lying!”: Orson Welles’s Deconstruction of Traditional Historiographies in Chimes at Midnight Jeffrey Yeager, West Virginia University ew Shakespearean films were so underappreciated at their release as Orson Welles’s Chimes at Midnight.1 Compared F to Laurence Olivier’s morale boosting 1944 version of Henry V, Orson Welles’s adaptation has never reached a wide audience, partly because of its long history of being in copyright limbo.2 Since the film’s debut, a critical tendency has been to read it as a lament for “Merrie England.” In an interview, Welles claimed: “It is more than Falstaff who is dying. It’s the old England, dying and betrayed” (qtd. in Hoffman 88). Keith Baxter, the actor who plays Prince Hal, expressed the sentiment that Hal was the principal character: Welles “always saw it as a triangle basically, a love story of a Prince lost between two father figures. Who is the boy going to choose?” (qtd. in Lyons 268). Samuel Crowl later modified these differing assessments by adding his own interpretation of Falstaff as the central character: “it is Falstaff’s winter which dominates the texture of the film, not Hal’s summer of self-realization” (“The Long Good-bye” 373). Michael Anderegg concurs with the assessment of Falstaff as the central figure when he historicizes the film by noting the film’s “conflict between rhetoric and history” on the one hand and “the immediacy of a prelinguistic, prelapsarian, timeless physical world, on the other” (126). By placing the focus on Falstaff and cutting a great deal of text, Welles, Anderegg argues, deconstructs Shakespeare’s world by moving “away from history and toward satire” (127). -

The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979

Charles Deering McCormick Library of Special Collections Northwestern University Libraries Dublin Gate Theatre Archive The Dublin Gate Theatre Archive, 1928 - 1979 History: The Dublin Gate Theatre was founded by Hilton Edwards (1903-1982) and Micheál MacLiammóir (1899-1978), two Englishmen who had met touring in Ireland with Anew McMaster's acting company. Edwards was a singer and established Shakespearian actor, and MacLiammóir, actually born Alfred Michael Willmore, had been a noted child actor, then a graphic artist, student of Gaelic, and enthusiast of Celtic culture. Taking their company’s name from Peter Godfrey’s Gate Theatre Studio in London, the young actors' goal was to produce and re-interpret world drama in Dublin, classic and contemporary, providing a new kind of theatre in addition to the established Abbey and its purely Irish plays. Beginning in 1928 in the Peacock Theatre for two seasons, and then in the theatre of the eighteenth century Rotunda Buildings, the two founders, with Edwards as actor, producer and lighting expert, and MacLiammóir as star, costume and scenery designer, along with their supporting board of directors, gave Dublin, and other cities when touring, a long and eclectic list of plays. The Dublin Gate Theatre produced, with their imaginative and innovative style, over 400 different works from Sophocles, Shakespeare, Congreve, Chekhov, Ibsen, O’Neill, Wilde, Shaw, Yeats and many others. They also introduced plays from younger Irish playwrights such as Denis Johnston, Mary Manning, Maura Laverty, Brian Friel, Fr. Desmond Forristal and Micheál MacLiammóir himself. Until his death early in 1978, the year of the Gate’s 50th Anniversary, MacLiammóir wrote, as well as acted and designed for the Gate, plays, revues and three one-man shows, and translated and adapted those of other authors. -

Teaching Writing with Images: the Role of Authorship and Self-Reflexivity in Audiovisual Essay Pedagogy

Repositorium für die Medienwissenschaft Roberto Letizi; Simon Troon Teaching writing with images: The role of authorship and self-reflexivity in audiovisual essay pedagogy 2020 https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/15347 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Letizi, Roberto; Troon, Simon: Teaching writing with images: The role of authorship and self-reflexivity in audiovisual essay pedagogy. In: NECSUS_European Journal of Media Studies. #Method, Jg. 9 (2020), Nr. 2, S. 181– 202. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25969/mediarep/15347. Erstmalig hier erschienen / Initial publication here: https://necsus-ejms.org/teaching-writing-with-images-the-role-of-authorship-and-self-reflexivity-in-audiovisual-essay- pedagogy/ Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Creative Commons - This document is made available under a creative commons - Namensnennung - Nicht kommerziell - Keine Bearbeitungen 4.0/ Attribution - Non Commercial - No Derivatives 4.0/ License. For Lizenz zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz more information see: finden Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF MEDIA STUDIES www.necsus-ejms.org Teaching writing with images: The role of authorship and self-reflexivity in audiovisual essay pedagogy Roberto Letizi & Simon Troon NECSUS 9 (2), Autumn 2020: 181–202 URL: https://necsus-ejms.org/teaching-writing-with-images-the- role-of-authorship-and-self-reflexivity-in-audiovisual-essay-peda- gogy/ Abstract Methodologies for teaching audiovisual essays often map the disci- pline-specific objectives of the form and the practical and philosoph- ical advantages it offers as a mode of assessment. -

Orson Welles: CHIMES at MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 Min

October 18, 2016 (XXXIII:8) Orson Welles: CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 min. Directed by Orson Welles Written by William Shakespeare (plays), Raphael Holinshed (book), Orson Welles (screenplay) Produced by Ángel Escolano, Emiliano Piedra, Harry Saltzman Music Angelo Francesco Lavagnino Cinematography Edmond Richard Film Editing Elena Jaumandreu , Frederick Muller, Peter Parasheles Production Design Mariano Erdoiza Set Decoration José Antonio de la Guerra Costume Design Orson Welles Cast Orson Welles…Falstaff Jeanne Moreau…Doll Tearsheet Worlds" panicked thousands of listeners. His made his Margaret Rutherford…Mistress Quickly first film Citizen Kane (1941), which tops nearly all lists John Gielgud ... Henry IV of the world's greatest films, when he was only 25. Marina Vlady ... Kate Percy Despite his reputation as an actor and master filmmaker, Walter Chiari ... Mr. Silence he maintained his memberships in the International Michael Aldridge ...Pistol Brotherhood of Magicians and the Society of American Tony Beckley ... Ned Poins and regularly practiced sleight-of-hand magic in case his Jeremy Rowe ... Prince John career came to an abrupt end. Welles occasionally Alan Webb ... Shallow performed at the annual conventions of each organization, Fernando Rey ... Worcester and was considered by fellow magicians to be extremely Keith Baxter...Prince Hal accomplished. Laurence Olivier had wanted to cast him as Norman Rodway ... Henry 'Hotspur' Percy Buckingham in Richard III (1955), his film of William José Nieto ... Northumberland Shakespeare's play "Richard III", but gave the role to Andrew Faulds ... Westmoreland Ralph Richardson, his oldest friend, because Richardson Patrick Bedford ... Bardolph (as Paddy Bedford) wanted it. In his autobiography, Olivier says he wishes he Beatrice Welles .. -

Roger Ebert's

The College of Media at Illinois presents Roger19thAnnual Ebert’s Film Festival2017 April 19-23, 2017 The Virginia Theatre Chaz Ebert: Co-Founder and Producer 203 W. Park, Champaign, IL Nate Kohn: Festival Director 2017 Roger Ebert’s Film Festival The University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign The College of Media at Illinois Presents... Roger Ebert’s Film Festival 2017 April 19–23, 2017 Chaz Ebert, Co-Founder, Producer, and Host Nate Kohn, Festival Director Casey Ludwig, Assistant Director More information about the festival can be found at www.ebertfest.com Mission Founded by the late Roger Ebert, University of Illinois Journalism graduate and a Pulitzer Prize- winning film critic, Roger Ebert’s Film Festival takes place in Urbana-Champaign each April for a week, hosted by Chaz Ebert. The festival presents 12 films representing a cross-section of important cinematic works overlooked by audiences, critics and distributors. The films are screened in the 1,500-seat Virginia Theatre, a restored movie palace built in the 1920s. A portion of the festival’s income goes toward on-going renovations at the theatre. The festival brings together the films’ producers, writers, actors and directors to help showcase their work. A film- maker or scholar introduces each film, and each screening is followed by a substantive on-stage Q&A discussion among filmmakers, critics and the audience. In addition to the screenings, the festival hosts a number of academic panel discussions featuring filmmaker guests, scholars and students. The mission of Roger Ebert’s Film Festival is to praise films, genres and formats that have been overlooked. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} Citizen Kane Ebook, Epub

CITIZEN KANE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Harlan Lebo | 368 pages | 01 May 2016 | Thomas Dunne Books | 9781250077530 | English | United States Citizen Kane () - IMDb Mankiewicz , who had been writing Mercury radio scripts. One of the long-standing controversies about Citizen Kane has been the authorship of the screenplay. In February Welles supplied Mankiewicz with pages of notes and put him under contract to write the first draft screenplay under the supervision of John Houseman , Welles's former partner in the Mercury Theatre. Welles later explained, "I left him on his own finally, because we'd started to waste too much time haggling. So, after mutual agreements on storyline and character, Mank went off with Houseman and did his version, while I stayed in Hollywood and wrote mine. The industry accused Welles of underplaying Mankiewicz's contribution to the script, but Welles countered the attacks by saying, "At the end, naturally, I was the one making the picture, after all—who had to make the decisions. I used what I wanted of Mank's and, rightly or wrongly, kept what I liked of my own. The terms of the contract stated that Mankiewicz was to receive no credit for his work, as he was hired as a script doctor. Mankiewicz also threatened to go to the Screen Writers Guild and claim full credit for writing the entire script by himself. After lodging a protest with the Screen Writers Guild, Mankiewicz withdrew it, then vacillated. The guild credit form listed Welles first, Mankiewicz second. Welles's assistant Richard Wilson said that the person who circled Mankiewicz's name in pencil, then drew an arrow that put it in first place, was Welles. -

Shak Shakespeare Shakespeare

Friday 14, 6:00pm ROMEO Y JULIETA ’64 / Ramón F. Suárez (30’) Cuba, 1964 / Documentary. Black-and- White. Filming of fragments of Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet staged by the renowned Czechoslovak theatre director Otomar Kreycha. HAMLET / Laurence Olivier (135’) U.K., 1948 / Spanish subtitles / Laurence Olivier, Eileen Herlie, Basil Sydney, Felix Aylmer, Jean Simmons. Black-and-White. Magnificent adaptation of Shakespeare’s tragedy, directed by and starring Olivier. Saturday 15, 6:00pm OTHELLO / The Tragedy of Othello: The Moor of Venice / Orson Welles (92’) Italy-Morocco, 1951 / Spanish subtitles / Orson Welles, Michéal MacLiammóir, Suzanne Cloutier, Robert Coote, Michael Laurence, Joseph Cotten, Joan Fontaine. Black- and-White. Filmed in Morocco between the years 1949 and 1952. Sunday 16, 6:00pm ROMEO AND JULIET / Franco Zeffirelli (135’) Italy-U.K., 1968 / Spanish subtitles / Leonard Whiting, Olivia Hussey, Michael York, John McEnery, Pat Heywood, Robert Stephens. Thursday 20, 6:00pm MACBETH / The Tragedy of Macbeth / Roman Polanski (140’) U.K.-U.S., 1971 / Spanish subtitles / Jon Finch, Francesca Annis, Martin Shaw, Nicholas Selby, John Stride, Stephan Chase. Colour. This version of Shakespeare’s key play is co-scripted by Kenneth Tynan and director Polanski. Friday 21, 6:00pm KING LEAR / Korol Lir / Grigori Kozintsev (130’) USSR, 1970 / Spanish subtitles / Yuri Yarvet, Elsa Radzin, GalinaVolchek, Valentina Shendrikova. Black-and-White. Saturday 22, 6:00pm CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT / Orson Welles (115’) Spain-Switzerland, 1965 / in Spanish / Orson Welles, Keith Baxter, John Gielgud, Jeanne Moreau, Margaret 400 YEARS ON, Rutherford, Norman Rodway, Marina Vlady, Walter Chiari, Michael Aldridge, Fernando Rey. Black-and-White. Sunday 23, 6:00pm PROSPERO’S BOOKS / Peter Greenaway (129’) U.K.-Netherlands-France, 1991 / Spanish subtitles / John Gielgud, Michael Clark, Michel Blanc, Erland Josephson, Isabelle SHAKESPEARE Pasco. -

The Booklet That Accompanied the Exhibition, With

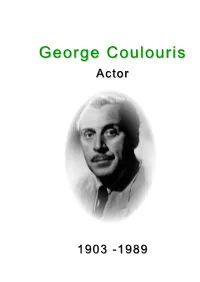

GGeeoorrggee CCoouulloouurriiss AAccttoorr 11990033 --11998899 George Coulouris - Biographical Notes 1903 1st October: born in Ordsall, son of Nicholas & Abigail Coulouris c1908 – c1910: attended a local private Dame School c1910 – 1916: attended Pendleton Grammar School on High Street c1916 – c1918: living at 137 New Park Road and father had a restaurant in Salisbury Buildings, 199 Trafford Road 1916 – 1921: attended Manchester Grammar School c1919 – c1923: father gave up the restaurant Portrait of George aged four to become a merchant with offices in Salisbury Buildings. George worked here for a while before going to drama school. During this same period the family had moved to Oakhurst, Church Road, Urmston c1923 – c1925: attended London’s Central School of Speech and Drama 1926 May: first professional stage appearance, in the Rusholme (Manchester) Repertory Theatre’s production of Outward Bound 1926 October: London debut in Henry V at the Old Vic 1929 9th Dec: Broadway debut in The Novice and the Duke 1933: First Hollywood film Christopher Bean 1937: played Mark Antony in Orson Welles’ Mercury Theatre production of Julius Caesar 1941: appeared in the film Citizen Kane 1950 Jan: returned to England to play Tartuffe at the Bristol Old Vic and the Lyric Hammersmith 1951: first British film Appointment With Venus 1974: played Dr Constantine to Albert Finney’s Poirot in Murder On The Orient Express. Also played Dr Roth, alongside Robert Powell, in Mahler 1989 25th April: died in Hampstead John Koulouris William Redfern m: c1861 Louisa Bailey b: 1832 Prestbury b: 1842 Macclesfield Knutsford Nicholas m: 10 Aug 1902 Abigail Redfern Mary Ann John b: c1873 Stretford b: 1864 b: c1866 b: c1861 Greece Sutton-in-Macclesfield Macclesfield Macclesfield d: 1935 d: 1926 Urmston George Alexander m: 10 May 1930 Louise Franklin (1) b: Oct 1903 New York Salford d: April 1989 d: 1976 m: 1977 Elizabeth Donaldson (2) George Franklin Mary Louise b: 1937 b: 1939 Where George Coulouris was born Above: Trafford Road with Hulton Street going off to the right. -

Prince Hal and the Body Falstaff

Prince Hal and the Body Falstaff: Theatre as Psychic Space in Shakespeare’s 1&2 Henry IV by Elise Denbo (Queensborough Community College, City University of New York) ABSTRACT Aligning psychoanalytic and embodiment approaches, this paper focuses on 1&2Henry IV using Julia Kristeva’s concept of the imaginary father, a ‘maternal-paternal conglomerate,’ as a third space within primary-narcissism. While Hal’s ‘education’ has been analyzed in relation to dualities of order and disorder, few, if any have considered Falstaff as an intrapsychic figure of intimate revolt who supports the crafting of psychic- theatrical-imaginary space. Hal’s youthful narcissism and his ability to connect with the popular voice are explored as a result of Falstaff’s presence in the ‘prehistory’ of his kingship. Falstaff’s verbal copia, his ‘belly of tongues,’ recalls the unruly female tongue as the site of disorder, but also the mother tongue that confers national identity as a return to the vernacular richness of the land and its people. While Hal is able to organize the various dialects and settings of 1&2HenryIV, it is the body Falstaff who impregnates the play. Keywords: Kristeva, Prince Hal and Falstaff, Psychic Space, Early Modern Theatre, Primary Narcissism, Shakespeare To cite as: Denbo, Elise 2020, “Prince Hal and the Body Falstaff: Theatre as Psychic Space in Shakespeare’s 1&2 Henry IV,” PsyArt, pp. 177-220. Prince Hal and the Body Falstaff: Theatre as Psychic Space in Shakespeare’s 1&2 Henry IV Prince Harry: I know you all, and will a while uphold The unyoked humour of your idelness. -

THE WAR of the WORLDS - SCRIPT - Orson Welles & T

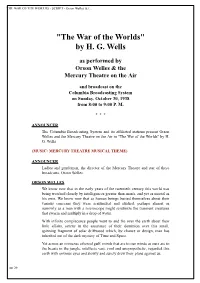

THE WAR OF THE WORLDS - SCRIPT - Orson Welles & t... "The War of the Worlds" by H. G. Wells as performed by Orson Welles & the Mercury Theatre on the Air and broadcast on the Columbia Broadcasting System on Sunday, October 30, 1938 from 8:00 to 9:00 P. M. * * * ANNOUNCER The Columbia Broadcasting System and its affiliated stations present Orson Welles and the Mercury Theatre on the Air in "The War of the Worlds" by H. G. Wells. (MUSIC: MERCURY THEATRE MUSICAL THEME) ANNOUNCER Ladies and gentlemen, the director of the Mercury Theatre and star of these broadcasts, Orson Welles. ORSON WELLES We know now that in the early years of the twentieth century this world was being watched closely by intelligences greater than man's, and yet as mortal as his own. We know now that as human beings busied themselves about their various concerns they were scrutinized and studied, perhaps almost as narrowly as a man with a microscope might scrutinize the transient creatures that swarm and multiply in a drop of water. With infinite complacence people went to and fro over the earth about their little affairs, serene in the assurance of their dominion over this small, spinning fragment of solar driftwood which, by chance or design, man has inherited out of the dark mystery of Time and Space. Yet across an immense ethereal gulf, minds that are to our minds as ours are to the beasts in the jungle, intellects vast, cool and unsympathetic, regarded this earth with envious eyes and slowly and surely drew their plans against us. -

Oconnor Conversations Spread

CONVERSATIONS WITH ORSON COLLEEN O’CONNOR #86 ESSAY PRESS NEXT SERIES Authors in the Next series have received finalist Contents recognition for book-length manuscripts that we think deserve swift publication. We offer an excerpt from those manuscripts here. Series Editors Maria Anderson Introduction vii Andy Fitch by David Lazar Ellen Fogelman Aimee Harrison War of the Worlds 1 Courtney Mandryk Grover’s Mill, New Jersey, 1938 Victoria A. Sanz Travis A. Sharp The Third Man 6 Ryan Spooner Vienna, 1949 Alexandra Stanislaw Citizen Kane 11 Series Assistants Cristiana Baik Ryan Ikeda Xanadu, Florida, 1941 Christopher Liek Emily Pifer Touch of Evil 17 Randall Tyrone Mexico/U.S. Border, 1958 Cover Design Ryan Spooner F for Fake 22 Ibiza, Spain, 1975 Composition Aimee Harrison Acknowledgments & Notes 24 Author Bio 26 Introduction — David Lazar “Desire is an acquisition,” Colleen O’Connor writes in her unsettling series, Conversations with Orson. And much of desire is dark and escapable, the original noir of noir. The narrator is and isn’t O’Connor. Just as Orson is and isn’t Welles. Orson/O’Connor. O, the plasticity of persona. There is a perverse desire to be both known and unknown in these pieces, fragments of essay, prose poems, bad dreams. How to wrap around a signifier that big, that messy, spilling out so many shadows! Colleen O’Connor pierces her Orson Welles with pity and recognition. We imagine them on Corsica thanks to a time machine, her vivid imagination, and a kind of bad cinematic hangover. The hair of the dog is the deconstruction of the male gaze.