Migration and the Urban Question in Kolkata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tollygunge Assembly West Bengal Factbook

Editor & Director Dr. R.K. Thukral Research Editor Dr. Shafeeq Rahman Compiled, Researched and Published by Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. D-100, 1st Floor, Okhla Industrial Area, Phase-I, New Delhi- 110020. Ph.: 91-11- 43580781, 26810964-65-66 Email : [email protected] Website : www.electionsinindia.com Online Book Store : www.datanetindia-ebooks.com Report No. : AFB/WB-152-0619 ISBN : 978-93-5293-827-8 First Edition : January, 2018 Third Updated Edition : June, 2019 Price : Rs. 11500/- US$ 310 © Datanet India Pvt. Ltd. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical photocopying, photographing, scanning, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. Please refer to Disclaimer at page no. 167 for the use of this publication. Printed in India No. Particulars Page No. Introduction 1 Assembly Constituency at a Glance | Features of Assembly as per 1-2 Delimitation Commission of India (2008) Location and Political Maps 2 Location Map | Boundaries of Assembly Constituency in District | Boundaries 3-9 of Assembly Constituency under Parliamentary Constituency | Ward-wise Winner Parties- 2019, 2016, 2014, 2011 and 2009 Administrative Setup 3 District | Sub-district | Towns | Villages | Inhabited Villages | Uninhabited 10 Villages | Village Panchayat | Intermediate Panchayat Demographics 4 Population | Households | Rural/Urban Population | Ward by Population Size | 11-12 Sex Ratio (Total & 0-6 Years) | Religious -

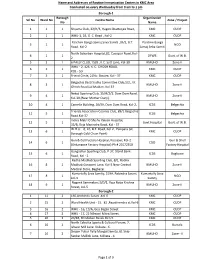

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area

Name and Addresses of Routine Immunization Centers in KMC Area Conducted on every Wednesday from 9 am to 1 pm Borough-1 Borough Organization Srl No Ward No Centre Name Zone / Project No Name 1 1 1 Shyama Club, 22/H/3, Hagen Chatterjee Road, KMC CUDP 2 1 1 WHU-1, 1B, G. C. Road , Kol-2 KMC CUDP Paschim Banga Samaj Seva Samiti ,35/2, B.T. Paschim Banga 3 1 1 NGO Road, Kol-2 Samaj Seba Samiti North Subarban Hospital,82, Cossipur Road, Kol- 4 1 1 DFWB Govt. of W.B. 2 5 2 1 6 PALLY CLUB, 15/B , K.C. Sett Lane, Kol-30 KMUHO Zone-II WHU - 2, 126, K. C. GHOSH ROAD, 6 2 1 KMC CUDP KOL - 50 7 3 1 Friend Circle, 21No. Bustee, Kol - 37 KMC CUDP Belgachia Basti Sudha Committee Club,1/2, J.K. 8 3 1 KMUHO Zone-II Ghosh Road,Lal Maidan, Kol-37 Netaji Sporting Club, 15/H/2/1, Dum Dum Road, 9 4 1 KMUHO Zone-II Kol-30,(Near Mother Diary). 10 4 1 Camelia Building, 26/59, Dum Dum Road, Kol-2, ICDS Belgachia Friends Association Cosmos Club, 89/1 Belgachia 11 5 1 ICDS Belgachia Road.Kol-37 Indira Matri O Shishu Kalyan Hospital, 12 5 1 Govt.Hospital Govt. of W.B. 35/B, Raja Manindra Road, Kol - 37 W.H.U. - 6, 10, B.T. Road, Kol-2 , Paikpara (at 13 6 1 KMC CUDP Borough Cold Chain Point) Gun & Cell Factory Hospital, Kossipur, Kol-2 Gun & Shell 14 6 1 CGO (Ordanance Factory Hospital) Ph # 25572350 Factory Hospital Gangadhar Sporting Club, P-37, Stand Bank 15 6 1 ICDS Bagbazar Road, Kol - 2 Radha Madhab Sporting Club, 8/1, Radha 16 8 1 Madhab Goswami Lane, Kol-3.Near Central KMUHO Zone-II Medical Store, Bagbazar Kumartully Seva Samity, 519A, Rabindra Sarani, Kumartully Seva 17 8 1 NGO kol-3 Samity Nagarik Sammelani,3/D/1, Raja Naba Krishna 18 9 1 KMUHO Zone-II Street, kol-5 Borough-2 1 11 2 160,Arobindu Sarani ,Kol-6 KMC CUDP 2 15 2 Ward Health Unit - 15. -

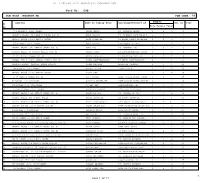

Ward No: 098 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Ward No: 098 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID Year No Male Female Total 1 7/2 KHANPUR SHAID NAGAR ABALA GAYAN LT. GOBINDA GAYAN 2 2 4 2 2 GANGULY BAGAN 23A GANGULY BAGAN KOL-92 ABHA BAGCHI LT. BHABANI PADA BAGCHI 4 3 7 3 3 NETAJI NAGAR 11/23 NETAJI NAGAR ALOK MUKERJEE LT BIMAL KANTI MUKERJEE 2 2 4 6 4 55 KHANPUR SOHID NAGAR AMAL BISWAS LATE GOPAL BISWAS 3 1 4 7 5 NETAJI NAGAR 2/42 NETAJI NAGAR KOL-92 AMAL DAS LT. MANMATO DAS 3 0 3 8 6 SUBHAS PALLY 33 SUBHAS PALLY, KOL 92 AMITA DUTTA LT LAKSHMINARAYAN DUTTA 0 1 1 9 7 7/11B NETAJI NAGAR KOL-92 AMIYA BALA SIL LT.NARENDRA NATH SIL 0 3 3 10 8 SUBHAS PALLY 32A/1 SUBHAS PALLY, KOL 92 ANIMA BHATTHACHARYA LT MUKUL BHATTACHARYA 0 1 1 11 9 GANGULY BAGAN GANGULY BAGAN KOL-92 ANIMA DEVNATH PRAFULLY DEVNATH 1 4 5 12 10 9A KHANPUR SOHIDNAGAR ANJALI SINHA JIBAN SINHA 1 2 3 13 11 NETAJI NAGAR 8/76C NETAJI NAGAR ANJAN DEY 2 2 4 14 12 1/37 NETAJI NAGAR KOL-92 ANJU DUTTA LATE SUSHIL KUMAR DUTTA 1 2 3 15 13 BIJOYGAR 5/17 BIJOYGAR ANURUPA MUKHERJEE LATE KOLLAN KUMAR MUKHERJ 0 1 1 16 14 POLLYSREE 15/1 POLLYSREE APURBA DEY HARAPRASANNA DEY 2 1 3 17 15 1/2/5 KHANPUR SAHID NAGAR ARABINDA BISWAS LATE SUSHIL BISWAS 1 1 2 18 16 NETAJI NAGAR 1/40 NETAJI NAGAR KOL-92 ARABINDA DAS LT. -

1 THIS DEED of SALE Is Made on This the Day of Twothousand

1 THIS DEED OF SALE is made on this the day of TwoThousand Nineteen B E T W E E N (1) SMT. RATNA CHAKRABORTY(PAN AUQPC3502M), wife of Sri Biplab Kumar. Chakraborty, residing at 128/4, Mahendra Banerjee Road, Behala, Kolkata – 700 060 (2) SRI RANJIT KUMAR GOSWAMI(PAN AZSPG3567H), son of late lateNilmoniGoswami (3) SMT KHUKU CHOWDHURY(PANAPTPC7249H), wife of late BenoyBhusan Chowdhury (4) SMT MIRA BOSE (PAN BEAPB2826J), wife of late Chittaranjan Bose (5) SMT BIJALI GOSWAMI(PAN AXGPG0456M), wife 2 Of late Anil Kumar Goswami, all owners no. 2,3,4 and 5 are residing at 6/83B, Bijoygarh, Kolkata – 700 032. (6) SMT BANANI LASKAR (PAN AGRPL4447K), daughter of late Anil Kr. Goswami, residing at 15, Regent Place, Kolkata – 700 040, (7) SRI SOMNATH GUHA(PAN AGJPG1151D), son of late SukhoranjanGuha, residing 84A, Pallisree, Kolkata – 700 092, (8) SRI PRABIR SENGUPTA(PANAJIPS7760A), son of Sri RanjitSengupta, residing at G-97, Baghajatin Colony, Kolkata – 700 086, all by nationality Indian, all by religion Hindu, all hereinafter collectively called and referred to as the “OWNERS” (which expression unless repugnant to the context shall mean and include their respective heirs, executors, administrators, representatives and assigns) of the FIRST PART. A N D (1) son/wife of and (2) , son/wife of , both by faith Hindu, both residing at , both hereinafter collectively referred to as the “PURCHASERS” (which expression shall unless excluded by or repugnant to the context be deemed to mean and include their respective heirs, executors, legal representatives, administrators and assigns) of the “THIRD PART”. A N D M/S S.S. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Salman Rushdie was on born 19 June 1947; he spent his childhood in Bombay but went to England at the age of fourteen to study at Rugby. He enrolled at Cambridge University to read history and afterwards lived mainly in Great Britain, before settling in the USA. After the Ayatollah Khomeini pronounced a fatwa against Rushdie and his novel The Satanic Verses (1988) in February 1989, Rushdie lived in hiding for several years but continued to write, produ- cing The Moor’s Last Sigh among other works. 2. The editions of the novels used are Midnight’s Children (MC) 1995, London: Vintage and The Moor’s Last Sigh (MLS) 1996, London: Vintage, and all page numbers in parentheses refer to these editions. 3. For a view similar to that of Brennan, see Conner 1997: 294–7. Teresa Heffernan likewise argues that Midnight’s Children is ‘from the outset sus- picious of the very model [...] of the modern nation’ (Heffernan 2000: 472); Thompson asserts that Rushdie eventually portrays the Indian nation as a ‘bad myth’ (Thompson 1995: 21). 4. See Bernd Hirsch 2001: 56–77. Heike Hartung focuses on exploring trends in western historiography in her study on the novels by Peter Ackroyd, Graham Swift and Salman Rushdie; she also briefly juxtaposes British and Indian his- toriography by contrasting the representation of the history of the Indian national movement in Percival Spear’s The Oxford History of India (1981) and Sumit Sarkar’s Modern India 1885–1947 (1989), without, however, making use of this material in her discussion of Rushdie’s novels (Hartung 2002: 235–41). -

Introduction

CHAPTER - I INTRODUCTION West Bengal is now the third most populous state in India, with a population density of a little more than 900 persons per square km. The state continues to attract a large number of migrants from neighbouring states as well as neighbouring countries. Its topography is dominated by the alluvial plains of the Ganga and its tributaries, except for the hilly terrain of North Bengal, extending into the Himalayan foothills. During the last few decades West Bengal has recorded high rates of agricultural growth. It also has a strong industrial base which needs to be further strengthened and diversified. Before we begin our detailed review of the situation of women in West Bengal, it would be useful to gain a broader perspective by looking at certain important socio-economic indicators which have been compiled in Tables S 1, S 2 and S 3. The first two Tables depict the position of West Bengal in an all-India context while the third presents a birds eye view of regional variations within the state of West Bengal, based on available district level information. West Bengals population growth rate during 1991-2001 has been 1.8 per cent per year, lower than the all-India annual growth of rate of 2.1 per cent. Similarly, levels of infant mortality, maternal mortality and total fertility are also well below the respective national averages. However, though the states female literacy rate at 60 per cent is appreciably higher than the all-India proportion of 54 per cent, its worker-population ratio for women at 18 per cent is substantially lower than the all-India figure of about 26 per cent. -

Annual Report 2011-12

Nature Mates-Nature Club 4/10A Bijoygarh, Kolkata-700032 Annual Report 2011-12 Regular Works 1. Maintenance of Banabitan Butterfly Garden We are maintaining this garden since 2010. During this financial year approximately 2500 numbers of butterflies were released. 15 new life cycles were documented. Other Works 2. We have assisted Centre for Contemporary Communication to do the Status Survey of Parks of Kolkata. The Report were prepared and submitted to CCC. 3. We have been assigned to assist the Wildlife Division II, Department of Forest, Government of West Bengal, to do the documentation of Butterfly fauna at Gorumara National Park. The work has been started during September 2011. 4. Many wildlife were rescued from in and around Kolkata and were given to the DRC Saltlake. 5. We have cleaned and restored the Santragachhi Jheel during September – November 2011. It was a huge success. Media covered our work with a lot of praise. 6. We are assigned by Creative Hortifirms Pvt Ltd to prepare a Biodiversity Status Report of their property at Panchla, named “Country Roads”. The work has started during July 2011. 7. We are assigned by GGL Hotel and Resort Company Ltd., Amubuja Reality to prepare a Biodiversity Status Report of their property at Raichak on Ganges. The work has started during August 2011. Nature Mates-Nature Club 4/10A Bijoygarh, Kolkata-700032 Annual Report 2012-13 Regular Works 1. Maintenance of Banabitan Butterfly Garden We are maintaining this garden since 2010. During this financial year approximately 3500 numbers of butterflies was released. 10 new life cycles were documented. -

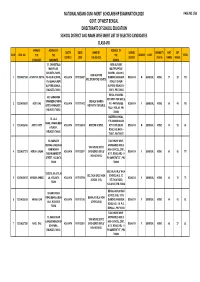

Kolkata Merit List

NATIONAL MEANS‐CUM ‐MERIT SCHOLARSHIP EXAMINATION,2020 PAGE NO.1/63 GOVT. OF WEST BENGAL DIRECTORATE OF SCHOOL EDUCATION SCHOOL DISTRICT AND NAME WISE MERIT LIST OF SELECTED CANDIDATES CLASS‐VIII NAME OF ADDRESS OF ADDRESS OF QUOTA UDISE NAME OF SCHOOL DISABILITY MAT SAT SLNO ROLL NO. THE THE THE GENDER CASTE TOTAL DISTRICT CODE THE SCHOOL DISTRICT STATUS MARKS MARKS CANDIDATE CANDIDATE SCHOOL 7/1, CHANDITALA NEW ALIPORE MAIN ROAD, MULTIPURPOSE KOLKATA-700053, SCHOOL, 23A/439/1, NEW ALIPORE 1 123204307048 ACHINTYA DUTTA PO- NEW ALIPORE, KOLKATA 19170108427 DIAMOND HARBOUR KOLKATA M GENERAL NONE 57 53 110 MULTIPURPOSE SCHOOL PS- BEHALA,NEW ROAD, P.O-NEW ALIPORE,BEHALA , ALIPORE, KOLKATA - KOLKATA 700053 700073, PIN-700053 BEHALA SHARDA 6/D, SARADAMA VIDYAPITH FOR GIRLS, UPANIBESH,PARNA BEHALA SHARDA 2 123204306005 ADITI DAS KOLKATA 19170113412 PO - PARNASREE KOLKATA F GENERAL NONE 60 49 109 SREE,PARNASREE , VIDYAPITH FOR GIRLS PALLY, KOL-60, PIN- KOLKATA 700060 700060 MODERN SCHOOL, TILJALA 17B, MANORANJAN ROAD,TANGRA,BENI 3 123204306180 ADITYA ROY KOLKATA 19170106510 MODERN SCHOOL ROY CHOUDHURI KOLKATA M GENERAL NONE 54 35 89 A PUKUR , ROAD, KOLKATA - KOLKATA 700046 700017, PIN-700017 3A RAMNATH TAKI HOUSE GOVT. BISWAS LANE,RAJA SPONSORED GIRLS' TAKI HOUSE GOVT. RAM MOHAN HIGH SCHOOL, 299C, 4 123204307075 ADRIJA BASAK KOLKATA 19170103911 SPONSORED GIRLS' KOLKATA F GENERAL NONE 61 56 117 SARANI,AMHERST A.P.C. ROAD, KOL - 9 HIGH SCHOOL STREET , KOLKATA PO AMHERST ST., PIN- 700009 700009 BELTALA GIRLS' HIGH 30/25,TILJALA,TILJA BELTALA GIRLS' HIGH SCHOOL (H.S), 17, 5 123204306135 AFREEN AHMED LA , KOLKATA KOLKATA 19170107506 KOLKATA F GENERAL NONE 44 31 75 SCHOOL (H.S) BELTALA ROAD, 700039 KALIGHAT, PIN-700026 BEHALA GIRLS HIGH 30 BARIK PARA SCHOOL(H.S), 337/4, ROAD,BEHALA,BEH BEHALA GIRLS HIGH 6 123204306129 AHANA DAS KOLKATA 19170112202 DIAMOND HARBOUR KOLKATA F GENERAL NONE 49 43 92 ALA , KOLKATA SCHOOL(H.S) ROAD, KOL - 34 P.O. -

City Executives Srl Name Designation D.O.B Area Tele

CITY EXECUTIVES SRL NAME DESIGNATION D.O.B AREA TELE. Residential address Year NO(R) 1 ALOKE KUMAR NANDI SDE (OFFTG) 27.04.1947 CITY 2455-7788 21, Turf Road, Bhowanipur, Kolkata- 25 2007 12, J.N. Sur Road, "Mahal Apartment ' 2nd floor, Chandannagar, Hooghly, 2 AMIYA BHUSAN MANDAL SDE / 2235 - INDOOR 18.03.1952 CITY 2685-5250 2012 Pin- 712136 3 ASIM KUMAR SIL JTO (OFFTG) 03.01.1951 CITY 2425-9766 2/1A, Acharya Profulla Chandra Park, Kol- 86. 2011 4 ASOKE KUMAR SAHA DGM(O) / NWO / CITY CITY 17.07.1952 2337-1686 B-8/2, Labony Estate. Salt Lake, Kolkata- 700064 2012 Trinath Apartment' , Flat -13 , FA5 Link road, 5 BABULAL MURMU SDE /220 /INTL 01.01.1949 CITY 2576-1828 2008 Deshbandhunagar, Baguiati, Kolkata- 700059 6 BALARAM CHANDRA SAHA SDE/OFFTG 13.07.1947 CITY 2500-7171 Mansa Villa' RG-2, Raghunathpur, Kolkata-59 2007 7 BHABES CHANDRA ROY J.T.O. 05.12.1950 CITY 2114-6877 94/2 M.M.Ghosh Road, DumDum Nager Bazer, Kol-74. 2010 DE/ INTL/TELE. 8 BISWA NATH KODALI 10.01.1949 CITY 2669-1269 Vill- Kamrangoo, P.O- Jhorehat, Dist- Howrah, Pin- 711302 2009 BHAVAN 9 DEBABRATA BAGCHI S.D.E CITY 15-02-1953 2677-0471 20/7 BRINDABAN MALLICK LANE, HOWRAH-711101 2013 Deep Appartment, AG-2, Sarat Sarani, Hanapara, Kestopur, 10 DHARANI KANTA DAS SARKAR DY. A.M. / CITY 26.06.1948 CITY 2591-1155 2008 Kolkata- 700102 01-09- 03213- Vill:- Bandhagachi, P.O- Guptipara, Dist- 11 DULAL CHANDRA SAHA D.E. -

62/9, Haripada Dutta Lane, Tollygunge, Kolkata- 700033

JADAVPUR EXECUTIVES SRL NAME DESIGNATION D.O.B AREA TELE. NO(R) Residential address Year 1 ACHYUTANANDA MANDAL DY. AREA MANAGER 06.01.1947 JDP 2402-6973 33/B, NaskarPara Road, P.O- Paschimputiary, Kol-41 2007 /JDP 2 AJAY KUMAR CHAKRABARTI DE/JDV & AM/JDV 01.03.1950 JDV 2425-1425 7, Chittaranjan Park, Flat- B/1, Sankalpa Co-operative, Jadavpur, 2010 Kolkata- 700032 3 AJIT KUMAR DEBNATH AGM / ADMIN / JDV 06.01.1951 JDP 2477-6151 Vill-Manikpur Ghosalpara, P.O-Harinavi, 24 Pgs (S), Kolkata -700148. 2011 4 AMIT KUMAR GUPTA DGM / NWO-JDP,Offg. 02.12.1951 JDV 2346-4646 1/4, Rajendra Banerjee Road, Behala, Kolkata- 700034 2011 5 AMIYA DAS 103223 07.02.1951 JDP 2410-1234 E-32,Kalachand Para,Kamdahari,P.O- Garia, Kol -700084 2011 6 AMIYA SANKAR GUPTA SDE / OFFTG./RLU-21 01.12.1948 JDP 2473-9950 52/A, Bank Colony , P.O- Dhakuria, Kolkata- 700031 2008 7 ANIL CHANDRA BISWAS SDE/OFFTG./CR-II/JDP 02.01.1950 JDP 2431-2100 B/25, Baudipur Road, P.O- Bansdroni, Kolkata- 700070 2010 8 ARUN KUMAR BANERJEE OFFTG/ DE/ RKT / 03.01.1948 JDV 2428-6060 226/5/1, N S C Bose road, Flat No. -03, Kolkata- 700092 2008 EXTL 9 ARUN ROY CHOWDHURY SDE / OFFTG 24.04.1950 JDP 2462-6161 East Balia, Balia Main Road, P.O- Garia, Kolkata- 700084 2010 10 ASHIM KUMAR SENGUPTA J.T.O. 04.01.1949 JDP 2422-5500 62/9, Haripada Dutta Lane, Tollygunge, Kolkata- 2009 700033 11 ASIS KUMAR HALDAR 100847 09.04.1952 JDP 2436-5596 F/154, B. -

The Scalar Quantification of Ɔnek 'Many'

THE SCALAR QUANTIFICATION OF ƆNEK ‘MANY’ IN BANGLA TISTA BAGCHI University of Delhi The interpretation of so-called vague quantifiers such as many is, at the conceptual-intentional interface, a straightforward one, on par with standard quantifiers such as the universal every and (in frameworks that recognize existential quantifiers) the existential a/an or some. However, while vague quantifiers display the same scopal behavior as standard ones do (at least at a “thick” level) at this interface, their quantificational status remains quite distinct from that of the standard quantifiers: they do not straightforwardly relate to the domains or sets defined by the nominal component that they are merged with (Barwise & Cooper 1981, Szabolcsi 2010). The behavior of an analogue in Bangla, viz., the quantifier ɔnek ‘many’, is the central focus of this paper, given that it can be used in both count and noncount senses, unlike in Hindi, in which anek, like many, is exclusively [+count]. Vandiver (2011a) argues that many in English can be placed on a stationary scale of quantifiers, from a/an through all. This paper, on the other hand, argues that such an explanation fails to account for the distinctive behavior of ɔnek with respect to (i) scope interaction with negation (where ɔnek is always wider in scope than any negation that it might co-occur with), (ii) semantic interaction with the Bangla classifier –tạ /-khani (versus no classifier), (iii) its use as a comparative quantifier on occasion with emphatic focus. Furthermore, the lower threshold for [+count] ɔnek might be determined by the maximum “paucal” number, possibly varying across speakers. -

Proceedings of the Regional Workshop on IMPLEMENTATION of PCPNDT ACT 1994 Organised by Institute of Development Studies Kolkata

+- Proceedings of The Regional Workshop on IMPLEMENTATION OF PCPNDT ACT 1994 Organised By Institute Of Development Studies Kolkata Calcutta University Alipore Campus, 5th Floor 1,ReformatoryStreet Kolkata 700 027 At Auditorium, Swasthya Bhaban, GN-29, Sector-V, Salt Lake, Kolkata-700 091 On 1-2 February 2006 Sponsored by: National Commission for Women 1. Background The Pre-conception and Pre-natal Diagnostic Techniques (PCPNDT) Act passed by the Indian Parliament came into force in 1994 for regulation and prevention of misuse of the diagnostic techniques. Subsequently, following a Supreme court order on its proper implementation certain amendments were made to the Act. The declining sex ratio in India particularly in the 0-6 year age group is a matter of grave concern. It was expected that proper implementation of the PCPNDT Act would check the pre-natal sex determination and elimination of the female foetus within the womb at least to some extent. However, although there has been ample time for implementing the Act, there is no sign that the decline in child sex ratio has been halted. Most states have set up the infrastructure prescribed in the Act, but this infrastructure is still to be effective. The problem of decline in sex ratio is very grave in Northern and Western India, particularly in those states that are said to be economically more developed. However, recent studies show that in certain parts of Eastern India too, the phenomenon has been fast catching up. For instance, the metropolitan areas of Kolkata show a steep decline in the sex ratio from 1991 to 2001 as far as the 0-6 year population group is concerned.