Holocaust High Priest Elie Wiesel, Night, the Memory Cult, and the Rise of Revisionism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter 2005/2006

Helping Lost Jewish Communities 11603 Gilsan Street Silver Spring, MD 20902-3122 KULANU TEL: 301-681-5679 FAX: 301-593-1911 http://www.kulanu.org “all of us” [email protected] Volume 11 Number 4 Winter 2004—2005 A Women’s Happening Texas Rabbi To Assist Veracruz Congregation In Uganda Rabbi Peter Tarlow, through the good graces of Kulanu and the hard The first Abayudaya women’s conference was held on December work of our Mexico coordinator, Amichai (Max) Heppner, was 14. Organized by Naume Sabano, president of the Abayudaya brought to Veracruz, Mexico, to meet with the local Texas Women’s Association, it attracted 65 participants from four Ugandan congregation. After a series of discussions, Rabbi Tarlow volunteered villages. to come to Veracruz four times a year to assist the congregation, which The program consisted of a D’var Torah by Mama Deborah Keki, had been formerly served by the late Rabbi Samuel Lerer. Tarlow is the president’s report, communications from the various synagogue fluent in Spanish and has a good understanding of Latin American representatives, the recitation of blessings on hearing sad news, hear- culture. He is the rabbi at the bi-lingual ing good news, and seeing the rainbow, and discussions on Nidah Texas A&M Hillel, and over the next few (Jewish purity laws), the life of Sarah, the observance of kashrut, and years, he hopes that some of his students the story of Ruth. may also be able to visit and work with The president urged the women to continue teaching young girls members of the congregation. -

Table of Contents

ANASTASIA LESTER LITERARY AGENT PRESENTS : SPRING2015 FICTION TABLE OF CONTENTS FICTION .............................................................................................. 3 BEST-SELLERS 2015 ..................................................................................... 3 HIGHLIGHT SPRING 2015 .......................................................................... 9 DISCOVERED WRITER ............................................................................. 19 LITERARY FICTION .................................................................................. 20 SHORT STORIES ......................................................................................... 27 NON-FRANCOPHONE AUTHORS ........................................................... 27 DEBUT NOVEL ............................................................................................ 28 WOMEN WRITING ..................................................................................... 32 CONTEMPORARY UP-MARKET COMMERCIAL TRENDS ............. 38 BIOGRAPHICAL & HISTORICAL NOVEL ........................................... 44 COMMERCIAL FICTION .......................................................................... 50 LITERARY CRIME & SUSPENSE NOVELS ........................................... 56 THRILLERS .................................................................................................. 61 SCIENCE-FICTION & FANTASY ............................................................. 65 YOUNG ADULT & CROSSE OVER ......................................................... -

Let My People Live! Forum

THE FOURTH INTERNATIONAL LET MY PEOPLE LIVE! FORUM LET MY PEOPLE LIVE! THE FOURTH INTERNATIONAL FORUM 26–27 JANUARY 2015 PRAGUE/TEREZIN CZECH REPUBLIC LET MY PEOPLE LIVE! THE FOURTH INTERNATIONAL FORUM INTERNATIONAL HOLOCAUST REMEMBRANCE DAY 70TH ANNIVERSARY Contents I. INTRODUCTION IV. CLOSING SESSION – PRAGUE CASTLE, Photographs from the Terezín Archives 7 SPANISH HALL – 27th January, 2015 119 Special messages: Prague Declaration on Combating Anti-Semitism and Hate Crimes 121 Moshe Kantor, President of the European Jewish Congress 17 Speeches by: Miloš Zeman, President of the Czech Republic 19 Miloš Zeman, President of the Czech Republic 122 Martin Schulz, President of the European Parliament 21 Martin Schulz, President of the European Parliament 124 Jean-Claude Juncker, President of the European Commission 23 Rosen Plevneliev, President of the Republic of Bulgaria 126 Yuli-Yoël Edelstein, Speaker of the Knesset 128 ‘Yellow Stars Concerto’ composed by Isaac Schwartz and II. FORUM OF WORLD CIVIL SOCIETY – PRAGUE CASTLE conducted by Maestro Vladimir Spivakov 132 SPANISH HALL – 26th January, 2015 25 Closing speech by Moshe Kantor, President of the European Jewish Congress 140 History of the Prague Castle 27 European Minute of Silence 142 Introductory speech by Moshe Kantor, President of the European Jewish Congress 37 Panel discussions Moderator: Stephen Sackur, BBC HARDtalk 46 V. TEREZÍN COMMEMORATION CEREMONY 147 Highlights of the discussions: Art Alley: Special extract from Vedem – magazine written Panel 1: The role of the media and public figures 50 and illustrated by children imprisoned in Terezín concentration camp 148 Panel 2: The role of legislation and law enforcement 68 The Story of Terezín 150 Panel 3: The role of politicians 80 EJC’s Monumental Tribute to Holocaust Survivors 152 Terezin Commemoration Ceremony 155 Zalud Musical Instruments & Poem 156 III. -

PROPAGANDA and HUMAN RIGHTS at ARGENTINA '78 by LIAM A. MACHADO a THESIS Presented to the Department Of

THE NATION ARRESTED: PROPAGANDA AND HUMAN RIGHTS AT ARGENTINA ‘78 by LIAM A. MACHADO A THESIS Presented to the Department of the History of Art and Architecture and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts June 2019 THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Student: Liam A. Machado Title: The Nation Arrested: Propaganda and Human Rights at Argentina ‘78 This thesis has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Department of the History of Art and Architecture by: Dr. Derek Burdette Chair Dr. Jenny Lin Member Dr. Keith Eggener Member and Janet Woodruff-Borden Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2019 ii © 2019 Liam A. Machado This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. iii THESIS ABSTRACT Liam A. Machado Master of Arts Department of the History of Art and Architecture June 2019 Title: The Nation Arrested: Propaganda and Human Rights at Argentina ‘78 This thesis examines the graphic design and propaganda generated by the 1978 FIFA World Cup in Argentina. The football tournament drew ever more scrutiny to the brutal repression carried out by the country’s military dictatorship, which had ruled Argentina since 1976. Increasingly, the World Cup became couched in terms of a conflict between morality and violence, innocence and conspiracy, with the dictatorship seeking to absolve itself through the image of a modern and welcoming event, and a European boycott strongly associating its repressive methods with the Holocaust. -

Select List of New Material

Select List of New Material - added in January 2013 CALL NUMBER TITLE PUBLISHER DATE Enemy within : 2,000 years of witch-hunting in the Western world / John BF1566 .D46 2008 Viking, 2008. Demos. Houghton Mifflin BF408 .L455 2012 Imagine : how creativity works / Jonah Lehrer. 2012. Harcourt, Science and religion : a historical introduction / edited by Gary B. Johns Hopkins University BL245 .S37 2002 2002. Ferngren. Press, Power of myth / Joseph Campbell, with Bill Moyers ; Betty Sue Flowers, BL304 .C36 1988 Doubleday, c1988. editor. Sacred causes : the clash of religion and politics, from the Great War to BL695 .B87 2007 HarperCollins, c2007. the War on Terror / Michael Burleigh. Popes against the Jews : the Vatican's role in the rise of modern anti- BM535 .K43 2001 Alfred A. Knopf, 2001. semitism / David I. Kertzer. BP173.J8 G65 2010 In Ishmael's house : a history of Jews in Muslim lands / Martin Gilbert. Yale University Press, 2010. Stanford University BP50 .S56 2003 Islam in a globalizing world / Thomas W. Simons, Jr. 2003. Press, BR145.2 .M69 2002 Faith : a history of Christianity / Brian Moynahan. Doubleday, 2002. Earthly powers : the clash of religion and politics in Europe from the BR475 .B87 2005 HarperCollins Publishers, c2005. French Revolution to the Great War / Michael Burleigh. Alfred A. Knopf : Moral reckoning : the role of the Catholic Church in the Holocaust and its BX1378 .G57 2002 c.2 Distributed by Random 2002. unfulfilled duty of repair / Daniel Jonah Goldhagen. House, BX1536 .W6413 2010 Pope and Devil : the Vatican's archives and the Third Reich / Hubert Wolf ; Belknap Press of Harvard 2010. -

Russian Nationalism

Russian Nationalism This book, by one of the foremost authorities on the subject, explores the complex nature of Russian nationalism. It examines nationalism as a multi layered and multifaceted repertoire displayed by a myriad of actors. It considers nationalism as various concepts and ideas emphasizing Russia’s distinctive national character, based on the country’s geography, history, Orthodoxy, and Soviet technological advances. It analyzes the ideologies of Russia’s ultra nationalist and far-right groups, explores the use of nationalism in the conflict with Ukraine and the annexation of Crimea, and discusses how Putin’s political opponents, including Alexei Navalny, make use of nationalism. Overall the book provides a rich analysis of a key force which is profoundly affecting political and societal developments both inside Russia and beyond. Marlene Laruelle is a Research Professor of International Affairs at the George Washington University, Washington, DC. BASEES/Routledge Series on Russian and East European Studies Series editors: Judith Pallot (President of BASEES and Chair) University of Oxford Richard Connolly University of Birmingham Birgit Beumers University of Aberystwyth Andrew Wilson School of Slavonic and East European Studies, University College London Matt Rendle University of Exeter This series is published on behalf of BASEES (the British Association for Sla vonic and East European Studies). The series comprises original, high quality, research level work by both new and established scholars on all aspects of Russian, -

Holocaust Denial

Holocaust Denial Holocaust Denial The Politics of Perfidy Edited by Robert Solomon Wistrich Co-published by The Hebrew University Magnes Press (Jerusalem) and De Gruyter (Berlin/Boston) for the Vidal Sassoon International Center for the Study of Antisemitism DE GRUYTER MAGNES An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org We would like to acknowledge the support of the Fondation pour la Mémoire de la Shoah in Paris which made possible the publication of this volume. Editorial Manager: Alifa Saadya An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libra- ries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org ISBN 978-3-11-021808-4 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-021809-1 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-021806-2 ISSN 0179-0986 e-ISSN 0179-3256 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 License, as of February 23, 2017. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/. ISBNLibrary 978-3-11-028814-8 of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data e-ISBNA CIP catalog 978-3-11-028821-9 record for this book has been applied for at the Library of Congress. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek LibraryDie Deutsche of Congress Nationalbibliothek Cataloging-in-Publication verzeichnet diese Data Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliogra- ISBN 978-3-11-021808-4 Afie; CIP detaillierte catalog record bibliografische for this book Daten has sindbeen im applied Internet for über at the Library of Congress. -

PRPL Master List 6-7-21

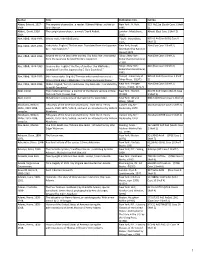

Author Title Publication Info. Call No. Abbey, Edward, 1927- The serpents of paradise : a reader / Edward Abbey ; edited by New York : H. Holt, 813 Ab12se (South Case 1 Shelf 1989. John Macrae. 1995. 2) Abbott, David, 1938- The upright piano player : a novel / David Abbott. London : MacLehose, Abbott (East Case 1 Shelf 2) 2014. 2010. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Warau tsuki / Abe Kōbō [cho]. Tōkyō : Shinchōsha, 895.63 Ab32wa(STGE Case 6 1975. Shelf 5) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Hakootoko. English;"The box man. Translated from the Japanese New York, Knopf; Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) by E. Dale Saunders." [distributed by Random House] 1974. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Beyond the curve (and other stories) / by Kobo Abe ; translated Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) from the Japanese by Juliet Winters Carpenter. Kodansha International, c1990. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Tanin no kao. English;"The face of another / by Kōbō Abe ; Tokyo ; New York : Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) [translated from the Japanese by E. Dale Saunders]." Kodansha International, 1992. Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Bō ni natta otoko. English;"The man who turned into a stick : [Tokyo] : University of 895.62 Ab33 (East Case 1 Shelf three related plays / Kōbō Abe ; translated by Donald Keene." Tokyo Press, ©1975. 2) Abe, Kōbō, 1924-1993. Mikkai. English;"Secret rendezvous / by Kōbō Abe ; translated by New York : Perigee Abe (East Case 1 Shelf 2) Juliet W. Carpenter." Books, [1980], ©1979. Abel, Lionel. The intellectual follies : a memoir of the literary venture in New New York : Norton, 801.95 Ab34 Aa1in (South Case York and Paris / Lionel Abel. -

Inter- Religious Dialogue

INTER- RELIGIOUS DIALOGUE SPECIAL REPORT | 9 - 15 OCTOBER 2018 http://eurac.tv/9PNc With the support of INTER- RELIGIOUS DIALOGUE SPECIAL REPORT | 9 - 15 OCTOBER 2018 Located at a crossroads of different civilizations, http://eurac.tv/9PNc Kazakhstan has placed great importance on promoting religious harmony and mutual respect. This year the country is hosting the sixth edition of the Congress of the Leaders of World and Traditional Religions, an initiative which has its roots in the aftermath of the 9/11 terrorist attacks. Contents Religion should not be used to sow divisions 4 Kazakh researcher: EU is like a dog with an Elizabethan collar 6 Religious leaders raise their flags at Astana gathering 9 A message from Astana: EU, be alert, the fascists are coming 11 Church leader: John Paul II left a legacy in Kazakhstan 13 4 9 - 15 OCTOBER 2018 | SPECIAL REPORT | INTER-RELIGIOUS DIALOGUE | EURACTIV OPINION DISCLAIMER: All opinions in this column reflect the views of the author(s), not of EURACTIV.COM Ltd. Religion should not be used to sow divisions By Kassym-Jomart Tokayev The Congress of the Leaders of World and Traditional Religions takes place in Astana, Kazakhstan. [Egemen Kazakhstan] n recent years, many thousands Kassym-Jomart Tokayev is a career other. Religious beliefs give direction, have died and millions more diplomat, chairman of Kazakhstan’s comfort and hope to billions of people. Ihad to flee their homes due to Senate and head of the Secretariat of the Religious communities appear conflicts in which religion has been Congress of the Leaders of World and to have enormous potential for used to justify discrimination and Traditional Religions.