Idea Submission Impossible?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

23 Strange Answers

23 ♦ Strange Answers Lawyer Plum was there and one pair of heirs when Otis Amber danced into the game room. “He-he-he, the Turtle’s lost its tail, I see.” Turtle slumped low in her chair. Flora Baumbach thought the short, sleek haircut was adorable, especially the way it swept forward over her little chin, but Turtle did not want to look adorable. She wanted to look mean. The dressmaker fumbled past the wad of money in her handbag. “Here, Alice, I thought you might like to see this.” Turtle glanced at the old snapshot. It’s Baba, all right, except younger. Same dumb smile. Suddenly she sat upright. “That’s my daughter, Rosalie,” Flora Baumbach said. “She must have been nine or ten when that picture was taken.” Rosalie was squat and square and squinty, her protruding tongue was too large for her mouth, her head lolled to one side. “I think I would have liked her, Baba,” Turtle said. “Rosalie looks like she was a very happy person. She must have been nice to have around.” Thump-thump, thump-thump. “Here come the victims,” Sydelle Pulaski announced. Angela greeted her sister with a wave of her crimson- streaked, healing hand. Turtle had convinced her not to confess: It would mean a criminal record, it would kill their mother, and no one would believe her anyhow. “I like your haircut.” “Thanks,” Turtle replied. Now Angela had to love her forever. Most of the heirs had to comment on Turtle’s hair. “You look like a real businesswoman,” Sandy said. -

Life on the Reef

INTERVIEW HOW TO BE… UK BAT DR SANDY KNAPP ON HER AN EXPERT SPECIES FASCINATION WITH PLANTS WITNESS 18 EXPLAINED THE SOCIETY OF BIOLOGY MAGAZINE ⁄www.societyofbiology.org ISSN 0006-3347 • Vol 62 No 3 • Jun/Jul 2015 LIFE ON THE REEF Unravelling the mysteries of coral NEWNEWNEW FROMFROM FROM GARLANDGARLAND GARLAND SCIENCE SCIENCE SCIENCE CellCellCell MembranesMembranes Membranes NEW FROM GARLANDLukasLukasLukas K.K. K. Buehler,Buehler, Buehler, SouthwesternSouthwestern Southwestern College, College, College, USA USASCIENCE USA CellCell CellMembranes Membranes Membranes offers offers offers a solida solid a solidfoundation foundation foundation for for for NEW FROM GARLANDunderstandingunderstandingunderstanding the the structurethe structure structure andSCIENCE and functionand function function of biologicalof ofbiological biological NEW FROM GARLANDmembranes.membranes.membranes. SCIENCE The book explores the composition and dynamics of cell TheThe book book explores explores the the composition composition and and dynamics dynamics of cellof cell membranes—discussing the molecular and biological NEW FROM GARLANDmembranes—discussingmembranes—discussing theSCIENCE the molecular molecular and and biological biological diversity of its lipid and protein components and how the diversitydiversity of itsof itslipid lipid and and protein protein components components and and how how the the combinatorialcombinatorial richness richness of both of bothcomponents components explains explains the the Cell Membranes chemical,combinatorial mechanical, -

Seinfeld, the Movie an Original Screenplay by Mark Gavagan Contact

Seinfeld, The Movie an original screenplay by Mark Gavagan based on the "Seinfeld" television series by Larry David and Jerry Seinfeld contact: Cole House Productions (201) 320-3208 BLACK SCREEN: TEXT: "One year later ..." TEXT FADES: DEPUTY (O.S.) Well folks. You've paid your debt to society. Good luck and say out of trouble. FADE IN: EXT. LOWELL MASSACHUSETTS JAIL -- MORNING ROLL CREDITS. JERRY, GEORGE and ELAINE look impatient as they stand empty- handed, waiting for something. The DEPUTY walks back towards the jail building behind them. CUT TO: INT. LOWELL MASSACHUSETTS JAIL KRAMER is surrounded by teary-eyed guards and inmates. They love him. He's carrying a metal cafeteria tray covered with signatures, as well as scores of cards, notes and letters. Several in the crowd hug KRAMER. CUT TO: EXT. LOWELL MASSACHUSETTS JAIL KRAMER stumbles as he walks up to GEORGE, ELAINE and JERRY. CUT TO: EXT. SOMEWHERE IN RURAL MASSACHUSETTS -- DAY We see an ugly old school bus at a dead stop with the flashers on. "LARRY'S NYC BUS SERVICE" is painted sloppily on the side. An extremely old man herds dozens of stubborn sheep across the road. He's moving at an impossibly slow pace. CUT TO: INT. OLD SCHOOL BUS JERRY, GEORGE and ELAINE are sitting in bus's original kid- sized bench seats. They look bored and uncomfortable. 2. Cheerful KRAMER is in the front row chatting with the DRIVER and pointing at the animals outside. CUT TO: INT. HALLWAY IN FRONT OF JERRY'S APARTMENT -- LATER KRAMER & JERRY walk wearily towards their doors. -

Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions

Salve Regina University Digital Commons @ Salve Regina Pell Scholars and Senior Theses Salve's Dissertations and Theses 5-2010 Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions Stephanie Savage Salve Regina University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses Part of the Advertising and Promotion Management Commons, and the Marketing Commons Savage, Stephanie, "Junior Mints and Their Bigger Than Bite-Size Role in Complicating Product Placement Assumptions" (2010). Pell Scholars and Senior Theses. 54. https://digitalcommons.salve.edu/pell_theses/54 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Salve's Dissertations and Theses at Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pell Scholars and Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Salve Regina. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Savage 1 “Who’s gonna turn down a Junior Mint? It’s chocolate, it’s peppermint ─it’s delicious!” While this may sound like your typical television commercial, you can thank Jerry Seinfeld and his butter fingers for what is actually one of the most renowned lines in television history. As part of a 1993 episode of Seinfeld , subsequently known as “The Junior Mint,” these infamous words have certainly gained a bit more attention than the show’s writers had originally bargained for. In fact, those of you who were annoyed by last year’s focus on a McDonald’s McFlurry on NBC’s 30 Rock may want to take up your beef with Seinfeld’s producers for supposedly showing marketers the way to the future ("Brand Practice: Product Integration Is as Old as Hollywood Itself"). -

Indie TV: Innovation in Series Development Aymar Jean Christian Northwestern Univeristy I Spent Five Years Interviewing Creators

Indie TV: Innovation in series development DRAFT Aymar Jean Christian Northwestern Univeristy I spent five years interviewing creators of American web series, or independent television online,1 speaking with 134 producers and executives making and releasing scripted series independent of traditional network investment. No two series or creators were ever alike. Some were sci-fi comedies created by Trekkers, others urban dramas by black women. Nevertheless nearly every creator differentiated their work and products from traditional television in some way. Strikingly, whenever I ask if any particular creator inspired them to develop their own show independently, I heard one response more than any other: Felicia Day. Indie TV creators revere Day for her innovation in production and distribution: she developed a hit franchise, The Guild, outside network development processes. The Guild, a sitcom about a diverse group of gamers who sit at computers all day to play an MMORPG in the style of World of Warcraft, ran for six seasons, from 2007 to 2013, and spawned a music video, DVDs, comic books, a companion book, as well as marshaled the passions of hundreds of thousands of fans. By the end of its run, The Guild had amassed over 330,000 subscribers on YouTube, though it could also be seen on other portals. In my work I have seen The Guild emerge as central to the online indie TV industry’s case for itself as antidote to what ails Hollywood. Day initially pitched to Christian, A.J. (forthcoming). Indie TV: Innovation in Series Development, in Media Independence: 1 working with freedom or working for free?. -

Et Tu, Dude? Humor and Philosophy in the Movies of Joel And

ET TU, DUDE? HUMOR AND PHILOSOPHY IN THE MOVIES OF JOEL AND ETHAN COEN A Report of a Senior Study by Geoffrey Bokuniewicz Major: Writing/Communication Maryville College Spring, 2014 Date approved ___________, by _____________________ Faculty Supervisor Date approved ___________, by _____________________ Division Chair Abstract This is a two-part senior thesis revolving around the works of the film writer/directors Joel and Ethan Coen. The first seven chapters deal with the humor and philosophy of the Coens according to formal theories of humor and deep explication of their cross-film themes. Though references are made to most of their films in the study, the five films studied most in-depth are Fargo, The Big Lebowski, No Country for Old Men, Burn After Reading, and A Serious Man. The study looks at common structures across both the Coens’ comedies and dramas and also how certain techniques make people laugh. Above all, this is a study on the production of humor through the lens of two very funny writers. This is also a launching pad for a prospective creative screenplay, and that is the focus of Chapter 8. In that chapter, there is a full treatment of a planned script as well as a significant portion of written script up until the first major plot point. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Chapter - Introduction VII I The Pattern Recognition Theory of Humor in Burn After Reading 1 Explanation and Examples 1 Efficacy and How It Could Help Me 12 II Benign Violation Theory in The Big Lebowski and 16 No Country for Old Men Explanation and Examples -

TPP-2012-07-A Star Is Born

A Star IS BORN A S tar IS BByORN Kim Fernandez Renting out parking facilities for movie and T.V. filming can be lucrative and fun. everal times a year, Lance Lunsway, CAPP, senior director, park- ing and transportation, Georgia Institute of Technology, clears the decks—literally—on campus to make room for movie and television Sstars, production crews, and lots of people and vehicles. Location scouts have discovered that the school is a great place to film all sorts of scenes for movies and television, and Lunsway’s facilities are the perfect places to either be in the scenes ECTORSTOCK V themselves or serve as storage for all the vehicles a movie shoot brings with it. KSTOCK, KSTOCK, “A lot of it comes because they want to be on campus,” crew comes to town aren’t unusual—as one location N THI he says of the productions. “The university is a big one scout put it, every production comes with dozens of and we have a lot of TV and movie production here. One vehicles, and their drivers all want to park as close to show wanted the back of a parking lot off our student the action as possible. Parking garages, too, are attractive union to be in the background of a shot.” for shooting scenes when the lighting and sight lines Requests to use parking decks and lots when a movie are right. And a contract with a production company www.parking.org/tpp JULY 2012 | INTERNATIONAL PARKING INSTITUTE 37 Long story short, putting a garage or lot out there to location scouts and filming companies can equate to almost free money without much hassle. -

Using Film and Television to Instruct an Organizational Behavior Course Tom Kernodle, Touro University International and Berkeley College, USA

American Journal of Business Education – November 2009 Volume 2, Number 8 Effective Media Use: Using Film And Television To Instruct An Organizational Behavior Course Tom Kernodle, Touro University International and Berkeley College, USA ABSTRACT Media can be used to effectively teach Organizational Behavior (OB) concepts at the college level. University instructors have the option to employ several different methods of teaching in order to convey course concepts in the classroom. This article describes the effectiveness that five particular pieces of media can have on active learning in an undergraduate OB class. The films For Love of the Game, 300, and 12 Angry Men, as well as the episode All Due Respect of the television series The Sopranos and the episode Did I Stutter? of the television series The Office, will be analyzed. This article provides a background on each piece of media, as well practical suggestions on how to use them to instruct OB. Keywords: Organizational Behavior, Management Education, Media Use INTRODUCTION edia can be used to effectively teach Organizational Behavior (OB) concepts at the college level. University instructors have the option to employ several different methods of teaching in order to convey course concepts in the classroom. Various methods of pedagogy can be used to instruct MOB courses, such as review and discussion questions, point-counterpoint debates, individual and group exercises, ethical dilemma exercises, case incidences and video cases, and an integrative part-ending case (Robbins, 1998). College instructors face an ongoing challenge to find effective methods of teaching course topics to students. Textbooks lay the foundation for the concepts and theories pertaining to a particular subject, but it is the responsibility of the instructor to effectively convey these ideas to the students. -

TOWN of RYE – BOARD of ADJUSTMENT MEETING Wednesday, May 6, 2020 7:00 P.M

Draft BOA Minutes of 5/06/2020 TOWN OF RYE – BOARD OF ADJUSTMENT MEETING Wednesday, May 6, 2020 7:00 p.m. – via ZOOM Members Present: Chair Patricia Weathersby, Vice-Chair Shawn Crapo, Burt Dibble, Rob Patten and Greg Mikolaities Note: Member Charles Hoyt was also present to speak on one of the applications but was not sitting for the meeting. Present on behalf of the Town: Attorney Michael Donovan, Planning/Zoning Administrator Kimberly Reed and Building Inspector Peter Rowell I. CALL TO ORDER Chair Weathersby called the meeting to order via Zoom teleconferencing at 7:00 p.m. Statement by Patricia Weathersby: As chair of the Rye Zoning Board of Adjustment, I find that due to the State of Emergency declared by the Governor as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and in accordance with the Governor’s Emergency Order #12 pursuant to Executive Order 2020-04, this public body is authorized to meet electronically. Please note that there is no physical location to observe and listen contemporaneously to this meeting, which was authorized pursuant to the Governor’s Emergency Order. However, in accordance with the Emergency Order, I am confirming that we are providing public access to the meeting by telephone, with additional access possibilities by video and other electronic means. We are utilizing Zoom for this electronic meeting. All members of the board have the ability to communicate contemporaneously during this meeting through this platform, and the public has access to contemporaneously listen and, if necessary, participate in this meeting by dialing in to the following phone number: 646-558-8656 or by clicking on the following website address: www.zoom.com ID #889-7293-9456 Password: 860305. -

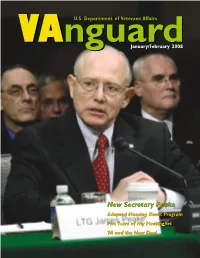

January/February 2008

VAnguard outlook January/February 2008 New Secretary Peake Adapted Housing Grant Program Five Years of My HealtheVet VA and the New Deal January/February 2008 1 VAnguard Features FY 2009 Budget Proposal: $93.7 Billion 6 Seamless transition, compensation and pension initiatives top priorities Honoring Distinguished Service in the Pacific 7 Coast Guard commandant visits Punchbowl to dedicate memorial ‘Granting’ Independence 8 6 Adapted housing program for seriously disabled veterans is growing In Tribute to America’s National Shrines 11 Author publishes book on VA national cemeteries Celebrating Five Years of My HealtheVet 1 2 More than 500,000 users are now registered on VA’s Web health portal On the Cusp of a Breakthrough 14 Dr. David Vesely’s cancer research is showing real promise VA and the New Deal 16 8 WPA helped construct Baltimore National Cemetery Taking the Reins 18 An interview with new Secretary James B. Peake, M.D. The Dream Cutter 22 L.A. barber donates services to lift the spirits of his fellow veterans Helping Veterans on the ‘Road to Recovery’ 23 VA employees lend their expertise at Disney World event ‘Wreaths Across America’ 24 Veterans buried in national cemeteries remembered at the holidays 22 Celebrating the Holidays VA-Style 25 Holiday happenings at facilities around the country VAnguard VA’s Employee Magazine Departments January/February 2008 3 Feedback 30 Medical Advances Vol. LIV, No. 1 4 From the Secretary 31 Heroes Printed on 50% recycled paper 5 Outlook 32 Have You Heard 26 Around Headquarters 34 Honors Editor: Lisa Respess Gaegler Photo Editor: Robert Turtil 29 Introducing 36 Holiday Wreaths Photographer: Art Gardiner Staff Writer: Amanda Hester Published by the Office of Public Affairs (80D) U.S. -

Even Without Outrageous Fight Scene, Film a Thinker's Thriller

PAGE b8 THE STATE JOURNAL JNUARA y 31, 2012 Tuesday RYA mE reel tAlk ALMANAC 50 YEARS AGO Miss Virginia Ann Greer, daughter of Mrs. W.F. Greer, made a 3.88 grade point av- ‘The Grey’ expertly crafted erage out of a possible 4.0 standing for the fall quar- ter at Michigan State Uni- versity, East Lansing, Mich. Even without outrageous fight scene, film a thinker’s thriller Miss Greer was a sophomore at MSU and a graduate of Frankfort High School. 25 YEARS AGO Kentucky State University scheduled cultural events, including poetry readings, lectures and films, as part of the university’s observance of Black History Month dur- ing February. Dr. Leonard A. Slade Jr., professor of Eng- lish and dean of the College Josh Raymer of Arts and Sciences at KSU, STATE JOURNAL ARTS ANd would present an evening of ENTERTAiNmENT WRiTER poetry readings in Hatha- way Hall Faculty Lounge. All f you’ve seen television events were free and open to previews for “The Grey” the public. then you know the out- rageous scene the mov- tYOdA in hiStORY Iie’s marketers have used to By The AssociATed Press sell it – Liam Neeson, broken Today is Tuesday, Jan. 31, bottles taped to one hand the 31st day of 2012. There are and a knife taped to the oth- 335 days left in the year. er, does battle with a blood- On Jan. 31, 1961, NASA thirsty wolf. launched Ham the Chimp That’s what drove this aboard a Mercury-Redstone critic to the theater on open- rocket from Cape Canaver- ing weekend, at least. -

How to Pitch TV Series in Hollywood

How to Pitch TV Series in Hollywood Partner, Citizen Media Bob Levy 目 次 1. American TV Pitch Format ....................................................................................... 2 1-1. Section 1: Personal Way into Series ................................................................... 4 1-2. Section 2: Concept of Series ............................................................................... 6 1-3. Section 3: World of Series ................................................................................ 10 1-4. Section 4: Characters ........................................................................................ 13 1-5. Section 5: Pilot Story ........................................................................................ 18 1-6. Section 6: Arc of First Season/Arc of Series .................................................... 24 1-7. Section 7: Tone ................................................................................................. 26 1-8. Section 8: Sample Episodes .............................................................................. 28 1-9. Q&A Conversation ........................................................................................... 30 2. TV Pitch Strategy .................................................................................................... 31 ‐1‐ 1. American TV Pitch Format Introduction While American TV has changed significantly in the past 15-20 years, the way new ideas for TV series in the U.S. are bought and sold has not. Since the beginning