Christopher Saner Pennsyfoania-Qerrnan ^Printer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cacapon Settlement: 1749-1800 31

THE CACAPON SETTLEMENT: 1749-1800 31 THE CACAPON SETTLEMENT: 1749-1800 31 5 THE CACAPON SETTLEMENT: 1749-1800 The existence of a settlement of Brethren families in the Cacapon River Valley of eastern Hampshire County in present day West Virginia has been unknown and uninvestigated until the present time. That a congregation of Brethren existed there in colonial times cannot now be denied, for sufficient evidence has been accumulated to reveal its presence at least by the 1760s and perhaps earlier. Because at this early date, Brethren churches and ministers did not keep records, details of this church cannot be recovered. At most, contemporary researchers can attempt to identify the families which have the highest probability of being of Brethren affiliation. Even this is difficult due to lack of time and resources. The research program for many of these families is incomplete, and this chapter is offered tentatively as a basis for additional research. Some attempted identifications will likely be incorrect. As work went forward on the Brethren settlements in the western and southern parts of old Hampshire County, it became clear that many families in the South Branch, Beaver Run and Pine churches had relatives who had lived in the Cacapon River Valley. Numerous families had moved from that valley to the western part of the county, and intermarriages were also evident. Land records revealed a large number of family names which were common on the South Branch, Patterson Creek, Beaver Run and Mill Creek areas. In many instances, the names appeared first on the Cacapon and later in the western part of the county. -

Abraham H. Cassel Collection 1610 Finding Aid Prepared by Sarah Newhouse

Abraham H. Cassel collection 1610 Finding aid prepared by Sarah Newhouse. Last updated on November 09, 2018. Historical Society of Pennsylvania August 2011 Abraham H. Cassel collection Table of Contents Summary Information....................................................................................................................................3 Administrative Information........................................................................................................................... 6 Related Materials........................................................................................................................................... 7 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................9 Bibliography.................................................................................................................................................10 Collection Inventory.................................................................................................................................... 11 - Page 2 - Abraham H. Cassel collection Summary Information Repository Historical Society of Pennsylvania Creator Cassel, Abraham Harley, 1820-1908. Title Abraham H. Cassel collection Call number 1610 Date [inclusive] 1680-1893 Extent 4.75 linear feet (48 volumes) Language German Language of Materials note Materials are mostly in German but there is some English. Books (00007021) [Volume] 23 Books (00007022) [Volume] 24 Books -

Ancienthistoricl00crol.Pdf

/ «?• ^ \ & \V1 -A^ 1-f^ '/ •M^ V^v I ANCIENT AND HISTORIC LANDMARKS IN THE Lebanon Valley. BY rev. f\ C. CROLL. 302736 Copyright, 1S95, by the LUTHERAN PUBLICATION SOCIETY « • » - * t 1 1 . < < < . c • c ' • < 1 1 < < 1 ( < i 1 » t ! < , 1 1 1 1 1 1 < < - • < <i( 1 < t 1 < <- CONTENTS PAGE Preface 7 Introduction, by Rev. W. H. Dunbar, D. D 9 CHAPTER I. A BIRD'S-EYE VIEW OF THE LEBANON VALLEY. An excursion— Motive —First settlement — imaginary— — Weekly trips A bird's-eye view of territory Beauty and richness of Valley—A goodly remnant of historic relics in the form of churches, graveyards, Indian forts, mills and homesteads . 13-17 CHAPTER II. CONRAD WEISER'S HOMESTEAD AND GRAVE. — A sacred shrine—The Weiser home and Exploration begun — pres- ent ownership—A noted marriage The Weiser burial plot— Its illustrious visitors — Brief sketch of Weiser 18-25 CHAPTER II r. MIDDLETOWN, ALIAS WOMELSDORF. Location and founding— Old streets and buildings—Its churches and schools— Old business center— Its graveyards— Worthy old families 26-37 CHAPTER IV. THE FIRST CHURCH IN THE VALLEY. Location of this historic shrine— Old landmarks en route—A cen- tury and three-quarters of local church history—Old graves. 3S-49 CHAPTER V. THE SECOND 1ULFEHOCKEN CHURCH. Church controversy—A new congregation — History of this flock— An ancient graveyard 50-57 CHAPTER VI. AN INTERESTING OLD MANSE. — One hundred and fifty years of pastoral family history Revs. Wagner, Kurtz, Schultze, Ulrich, Eggers, Mayser and Long. 58-65 CHAPTER VII. A WELL-PRESERVED INDIAN FORT. -

Hamilton College Library •Œhome Notesâ•Š

American Communal Societies Quarterly Volume 3 Number 2 Pages 100-108 April 2009 Hamilton College Library “Home Notes” Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/acsq This work is made available by Hamilton College for educational and research purposes under a Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 4.0 license. For more information, visit http://digitalcommons.hamilton.edu/about.html or contact [email protected]. et al.: Hamilton College Library “Home Notes” Hamilton College Library “Home Notes” Communal Societies Collection New Acquisitions [Broadside]. Lecture! [n.s., n.d.] Isabella Baumfree (Sojourner Truth) was born in 1797 on the Colonel Johannes Hardenbergh estate in Swartekill, Ulster County, a Dutch settlement in upstate New York. She spoke only Dutch until she was sold from her family around the age of nine. In 1829, Baumfree met Elijah Pierson, an enthusiastic religious reformer who led a small group of followers in his household called the “Kingdom.” She became the housekeeper for this group, and was encouraged to preach among them. Robert Matthias, also known as Matthias the Prophet, eventually took control of the group and instituted unorthodox religious and sexual practices. The “Kingdom” ended in public scandal. On June 1, 1843, Baumfree adopted the sobriquet Sojourner Truth. Unsoured by her experience in the “Kingdom” she joined the Northampton Association of Education and Industry in Massachusetts. This anti-slavery, pro-women’s rights group lived communally and manufactured silk. After the Northampton Association disbanded in 1846 Truth became involved with the Progressive Friends, an offshoot of the Quakers. Truth began her career in public speaking during the 1850s. -

Die Deutsche Emigration Nach Nordamerika 1683 Und 1709

Die deutsche Emigration nach Nordamerika 1683 und 1709 Religionsfreiheit als Faktor der Auswanderung und der Staatswerdung Pennsylvanias Diplomarbeit zur Erlangung des akademischen Grades eines Magisters der Philosophie an der Karl-Franzens-Universität vorgelegt von David KOBER am Institut für Geschichte Univ.-Prof. Mag. Dr.phil. Alois Kernbauer Ehrenwörtliche Erklärung Ich erkläre ehrenwörtlich, dass ich die vorliegende Arbeit selbstständig und ohne fremde Hilfe verfasst, andere als die angegebenen Quellen nicht benutzt und die den Quellen wörtlich oder inhaltlich entnommenen Stellen als solche kenntlich gemacht habe. Die Arbeit wurde bisher in gleicher oder ähnlicher Form keiner anderen inländischen oder ausländischen Prüfungsbehörde vorgelegt und noch nicht veröffentlicht. Die vorliegende Fassung entspricht der eingereichten elektronischen Version. __________________________ ______________________________ Datum, Ort Unterschrift Inhalt Einleitung ................................................................................................................................................. 2 1 Deutsche Einwanderungswellen nach Nordamerika, 1683 und 1709 ................................................. 5 1.1 Penns Reise 1677 und die Auswanderung von 1683 .................................................................... 5 1.2 Massenauswanderung der Pfälzer 1709 ..................................................................................... 12 2 Reiseberichte, Redemptioner und Menschenhandel ........................................................................ -

Early History of the Reformed Church

E ARL Y HI S T O RY O F T HE REFORMED CHU RCH IN P E N N YL V AN IA S . E BY D ANIEL MILL R . WIT H INT ROD U C T ION BY HIN D D . W . K . PROF J E, READIN G PA ’ 1 ’ E 23 NORTHSIXT HSTR ET . 229 56 OP R GHT 1 90 6 C Y I , , BYD ANIEL MILLER. RE E P F A C . To the author of this v olu me the early history of the Re formed Church in Pennsylvania has been the e n e e are subj ect of pl asant study for a lo g time. Th r many facts conn ected W ith this history Which are no t o nl e e e e c cu t d y int ns ly int r sting, but also al la e to prompt u e fu T he s to mor lly appreciate our religious h eritage . history is prese nted in plain lang uage and in a fo r m h be e e e w ich may r adily und rstood . It is oft n said that many writers assum e too much intelligence on the part the e e e e to e the co n of av rag r ad r, and fail giv all facts n t e ec ed With a subj ect . We have sought to pres nt all the e e e e e e the sali nt facts r lat d to a subj ct, v n at risk of e e e e e e e e r p ating som stat m nts, so as to mak matt rs asily understood . -

Die Kaufmannsfamilie Schlatter : Ein Überblick Über Vier Generationen

Die Kaufmannsfamilie Schlatter : ein Überblick über vier Generationen Autor(en): Kälin, Ursel Objekttyp: Article Zeitschrift: Schweizerische Zeitschrift für Geschichte = Revue suisse d'histoire = Rivista storica svizzera Band (Jahr): 48 (1998) Heft 3: Schweizerische Russlandmigration = Emigrations suisses en Russie PDF erstellt am: 11.10.2021 Persistenter Link: http://doi.org/10.5169/seals-81230 Nutzungsbedingungen Die ETH-Bibliothek ist Anbieterin der digitalisierten Zeitschriften. Sie besitzt keine Urheberrechte an den Inhalten der Zeitschriften. Die Rechte liegen in der Regel bei den Herausgebern. Die auf der Plattform e-periodica veröffentlichten Dokumente stehen für nicht-kommerzielle Zwecke in Lehre und Forschung sowie für die private Nutzung frei zur Verfügung. Einzelne Dateien oder Ausdrucke aus diesem Angebot können zusammen mit diesen Nutzungsbedingungen und den korrekten Herkunftsbezeichnungen weitergegeben werden. Das Veröffentlichen von Bildern in Print- und Online-Publikationen ist nur mit vorheriger Genehmigung der Rechteinhaber erlaubt. Die systematische Speicherung von Teilen des elektronischen Angebots auf anderen Servern bedarf ebenfalls des schriftlichen Einverständnisses der Rechteinhaber. Haftungsausschluss Alle Angaben erfolgen ohne Gewähr für Vollständigkeit oder Richtigkeit. Es wird keine Haftung übernommen für Schäden durch die Verwendung von Informationen aus diesem Online-Angebot oder durch das Fehlen von Informationen. Dies gilt auch für Inhalte Dritter, die über dieses Angebot zugänglich sind. Ein Dienst der ETH-Bibliothek ETH Zürich, Rämistrasse 101, 8092 Zürich, Schweiz, www.library.ethz.ch http://www.e-periodica.ch Die Kaufmannsfamilie Schlatter - ein Überblick über vier Generationen Ursel Kälin Resume L'histoire de la famille Schlatter de St-Gall sera suivie sur pres d'un siecle. Succombant ä l'attrait du large, Daniel Schlatter, fils de marchand, quitta sa ville natale pour visiter le sud de la Russie. -

The Eighteenth Century German Lutheran and Reformed Clergymen in the Susquehanna Valley*

THE EIGHTEENTH CENTURY GERMAN LUTHERAN AND REFORMED CLERGYMEN IN THE SUSQUEHANNA VALLEY* By CHARLES H. GLATFELTER T HE main facts of the German immigration into colonial lPennsylvania are well known. The promise of religious free- dom, the effect of advertising by William Penn and others, and the successful efforts of shipowners and their agents were factors which, either singly or in combination, brought thousands of dis- satisfied people into the province, the vast majority of them being from southwestern Germany and from Switzerland. Although there were a few scattered Germans in Pennsylvania before 1710, that year marks the beginning of significant immigration. From then until the Revolution the annual influx was considerable, reaching its climax during the years 1749-1754. There were times during the colonial period when the German population of Penn- sylvania approached one-half of the total, but after about 1765 the proportion slowly began to decline. It is probable that in 1790 one-third of the inhabitants of Pennsylvania were of German or Swiss extraction. Some of these immigrants remained in or near Philadelphia, where they were or became artisans. Many others helped to push the expanding frontier north and west of the capital, along the line of the Blue Mountains and eventually across the Susquehanna River. There were inducements which drew settlers into western Maryland, the Shenandoah valley of Virginia, and the back coun- try of North Carolina. Nevertheless, the hard core of German settlement in British America consisted of the colonial Pennsyl- vania counties of Northampton, Berks, Lancaster, and York. Even the county towns-Easton, Reading; Lancaster, and York-were predominately German in population. -

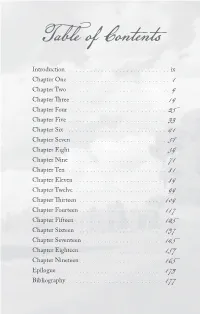

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Introduction ix Chapter One 1 Chapter Two �������������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 9 Chapter Three ������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 19 Chapter Four 25 Chapter Five ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 33 Chapter Six 41 Chapter Seven 51 Chapter Eight �������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 59 Chapter Nine 71 Chapter Ten 81 Chapter Eleven ���������������������������������������������������������������������������� 89 Chapter Twelve ����������������������������������������������������������������������������� 99 Chapter Thirteen ����������������������������������������������������������������������� 109 Chapter Fourteen 117 Chapter Fifteen 125 Chapter Sixteen 137 Chapter Seventeen 145 Chapter Eighteen 157 Chapter Nineteen 165 Epilogue 173 Bibliography �������������������������������������������������������������������������������� 177 Chapter One trail of wet footprints in the melting snow marked Christian’s path as he made his Away toward Peter Miller’s print shop near the Cocalico Creek at -

A History of the Goshenhoppen Reformed Charge, Montgomery

UNIVERSmy PENNSYIXWNIA. LIBRARIES penne^lpanfa: THE GERMAN INFLUENCE IN ITS SETTLEMENT AND DEVELOPMENT H IRartative anb Critical Ibistori? PREPARED BY AUTHORITY OF THE PENNSYLVANIA-GERMAN SOCIETY PART XXIX A HISTORY OF THE GOSHENHOPPEN REFORMED CHARGE PUBLISHED BY THE SOCIETY publication Committee. JULIUS F. SACHSE, Litt.D. DANIEIv W. NEAD, M.D. J. E. B. BUCKENHAM, M.D. ottbe (Bosbenboppen TRefotmeb Cbarge fiDontGomeri? County, ipennsiPlvania (1727^X819) Part XXIX of a Narrative and Critical History PREPARED AT THE REQUEST OF THE Pennsylvania-German Society By rev. WILLIAM JOHN HINKE, Ph.D., D.D. Professor of Semitic Languages and Religions in Auburn Theological Seminary, Auburn, New York LANCASTER 1920 Copyrighted 1920 BY THE lpcnn6iBlvania=(5ecman Society. PRESS OF THE NEW ERA PRINTING COMPANY LANCASTER, PA. PREFACE. Reformed Church History in this country has long been a subject of study. It is interesting to note that the first printed history of the Reformed Church in the United States was published not in America but in Germany. In the year 1846, the Rev. Dr. J. G. Buettner, the first pro- fessor of the first Theological Seminary in the State of Ohio, published " Die Hochdeutsche Reformirte Kirche in den Vereinigten Staaten von Nord-Amerika," in Schleiz, Germany. But even before that time, the Rev. Dr. Lewis Mayer, the first professor of the Reformed Theological Seminary at York, Pa., had been busy gathering materials for the history of the Reformed Church. Unfortunately he died at York, in 1849, before he had fully utilized the documents he had so carefully collected and copied. Only a brief sketch from his pen appeared in I. -

Pennsylvania History (People, Places, Events) Record Holdings Scholars in Residence Pennsylvania History Day People Places Events Things

rruVik.. reliulsyiVUtlll L -tiestuly ratge I UI I Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission Home Programs & Events Researchr Historic Sites & Museums Records Management About Us Historic Preservation Pennsylvania State Archives CRGIS: Cultural Resources Geographic Information Doc Heritage Digital Archives (ARIAS) 0OF ExplorePAhistory.com V Land Records things Genealogy Pennsylvania History (People, Places, Events) Record Holdings Scholars in Residence Pennsylvania History Day People Places Events Things Documentary Heritaae Pennsylvania Governors Symbols and Official Designations Examples: " Keystone State," Flower, Tree Penn-sylyania Counties Outline of Pennsylvania History 1, n-n. II, ni, tv, c.tnto ~ no Ii~, ol-, /~~h nt/n. mr. on, ,t on~~con A~2 1 .rrniV1%', reiniSy1Vdaina riiSiur'y ragcaeiuo I ()I U Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission lome Programs & Events Research Historic Sites & Museums Records Management About Us Historic Preservation Pennsylvania State Archives PENNSYLVANIA STATE CRGIS: Cultural Resources Geographic Information HISTO RY Doc Heritage Digital Archives (ARIAS) ExplorePAhistory.com Land Records THE QUAKER PROVINCE: 1681-1776 Genealogy Pennsylvania History . (People, Places, Events) Record Holdings Y Scholars in Residence Pennsylvania History Day The Founding of Pennsylvania William Penn and the Quakers Penn was born in London on October 24, 1644, the son of Admiral Sir William Penn. Despite high social position and an excellent education, he shocked his upper-class associates by his conversion to the beliefs of the Society of Friends, or Quakers, then a persecuted sect. He used his inherited wealth and rank to benefit and protect his fellow believers. Despite the unpopularity of his religion, he was socially acceptable in the king's court because he was trusted by the Duke of York, later King James II. -

Disabilities Awareness Month

Take These Worthy Causes to Church on Sunday Cov Kid Disabilities a io al & Families Awareness Do ot S bbath Today Month November 14 October As of February 1, 2003, more This October raise awareness of than 81,000 men, women and disability ministry by using materials children nationwide were Working families are eligible created by the Church and Persons waiting for organ transplants, for low-cost and free health with Disabilities Network, a ministry according to the U.S. Depart insurance through state and of ABC. Resources posted at ABC's ment of Health and Human federal programs. Help the website include: Services. Some 17 patients 8. 5 million uninsured kids in die each day while waiting. ■ Worship resources the United States obtain health Support organ and tissue care by talking about "Covering ■ Sunday school lessons donation by wearing donor pins Kids & Families," a nonprofit ■ Ideas for awareness raising and talking about National program funded by the Robert ■ Accessibility checklist Donor Sabbath during worship Woods Johnson Foundation, ■ Open Roof Award information this November 14. Donor pins in your church. To explore your ■ Funding suggestions and study /worship resources eligibility, call (877) KIDS-NOW are available from ABC: ■ Resources for adapting toll-free. Link to Covering Kids church rituals to those & Families online through ABC. with special needs. The Association of Brethren Caregivers encourages Association of congregations to honor these special emphases. Brethren Caregivers 1451 Dundee Ave., Elgin, Ill. 60120 (800) 323-8039 Resources are available at www.brethren.org/abc/. OCTOBER 2004 VOL.153 NO.9 WWW.BRETHREN.ORG u .