“You Can't Get a Man with A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Scribherms I Brought Bark by Request SPENCFR Healthfullv Air Conditioned

had ever heard of Fred's bulldogs Have they been lnnoculated? (In- signing Ginger Rogers. Ginger, 1 A Canines Also Demand and Sport Is Betty Hutton before, questions began to pour deed!) And heaven knows how Is well known, has more details lr Detailed Contracts over the wires to New York, such many more queries of the like. her contracts than any star In town as "Is this a dog act?” (You bet!) When the deal was finally con- from the size of her mlrrori The Studio Cheered as She Broadcast Br the Associated Press. makeup How many dogs In the troupe? cluded the legal department ad- to the dimensions of the type In hei When Kay Kyser starts on a to Director and Cast (Plenty!) Are they Insured? (Yes!) mitted it was more complicated than billings. Apologies picture, veterans around his studio By HAROLD HEFFF.RNAN. RKO. If the deal is set each other Luise will do began asking "What AMUSEMENTS. AMUSEMENTS. AMUSEMENTS. HOLLYWOOD. another "Good Earth" impersona- next?” For anything can and does _ and sounds: tion for on a Sights "China Skies.” .. Warner happen Kyser picture. Latest Even Preston Foster himself Bras, will shortly announce a re- complication Is Kay's whim to sign ! rubbed his eyes a bit over this sud- make of the Colleen Moore silent some vaudeville acts for the new den transformation. Within 15 hit "So Big” for Bette Davis. That opus. Including one act called minutes on the 20th Centurv-Fox makes five pictures on Bette's future “Fred’s Bulldogs.”* lot he went from the role of Roger chart, Paramount has granted When the casting director sent the Terrible Touhy in "Roger Touhy, Veronica Lake a long summer vaca- the contracts down to the legal de- Last of the Gangsters,” to the char- tion to recuperate from the double partment, the fun began. -

Does the Primetime Television Upfront Still Matter? by Steve Sternberg

May 2019 #62 __________________________________________________________________________________________ _____ Does the Primetime Television Upfront Still Matter? By Steve Sternberg For American television viewers, the start of the new primetime television season is still four months away. For insiders at media agencies, networks, and advertisers, however, the Upfront season is placing thoughts of September squarely into May. Of course, the very idea of a fall TV season in today’s video world seems old fashioned. The broadcast networks might still adhere to fall and mid-season schedules for debuting new shows, but their competitors do not. Ad-supported cable networks premiere many new series when the broadcast nets are airing repeats and some limited-run series (mostly non-sweeps months and the summer). Premium cable networks, such as HBO, Showtime, and Starz, air new shows throughout the year. Streaming services, such as Netflix and Amazon Prime, release full seasons of new series whenever they happen to be ready. CBS All Access does as well, although it releases new episodes on a weekly schedule, rather than all at once. In a television landscape of 10-episode cable series, and streaming services where you can binge- watch entire seasons, viewers don’t necessarily think in terms of TV seasons anymore. Nevertheless, the broadcast networks still hold onto a schedule that starts in the fall. Throughout April and May, cable and broadcast networks give presentations to the ad industry in which they unveil their fall schedules and discuss -

Broadway the BROAD Way”

MEDIA CONTACT: Fred Tracey Marketing/PR Director 760.643.5217 [email protected] Bets Malone Makes Cabaret Debut at ClubM at the Moonlight Amphitheatre on Jan. 13 with One-Woman Show “Broadway the BROAD Way” Download Art Here Vista, CA (January 4, 2018) – Moonlight Amphitheatre’s ClubM opens its 2018 series of cabaret concerts at its intimate indoor venue on Sat., Jan. 13 at 7:30 p.m. with Bets Malone: Broadway the BROAD Way. Making her cabaret debut, Malone will salute 14 of her favorite Broadway actresses who have been an influence on her during her musical theatre career. The audience will hear selections made famous by Fanny Brice, Carol Burnett, Betty Buckley, Carol Channing, Judy Holliday, Angela Lansbury, Patti LuPone, Mary Martin, Ethel Merman, Liza Minnelli, Bernadette Peters, Barbra Streisand, Elaine Stritch, and Nancy Walker. On making her cabaret debut: “The idea of putting together an original cabaret act where you’re standing on stage for ninety minutes straight has always sounded daunting to me,” Malone said. “I’ve had the idea for this particular cabaret format for a few years. I felt the time was right to challenge myself, and I couldn’t be more proud to debut this cabaret on the very stage that offered me my first musical theatre experience as a nine-year-old in the Moonlight’s very first musical Oliver! directed by Kathy Brombacher.” Malone can relate to the fact that the leading ladies she has chosen to celebrate are all attached to iconic comedic roles. “I learned at a very young age that getting laughs is golden,” she said. -

PLAYHOUSE SQUARE January 12-17, 2016

For Immediate Release January 2016 PLAYHOUSE SQUARE January 12-17, 2016 Playhouse Square is proud to announce that the U.S. National Tour of ANNIE, now in its second smash year, will play January 12 - 17 at the Connor Palace in Cleveland. Directed by original lyricist and director Martin Charnin for the 19th time, this production of ANNIE is a brand new physical incarnation of the iconic Tony Award®-winning original. ANNIE has a book by Thomas Meehan, music by Charles Strouse and lyrics by Martin Charnin. All three authors received 1977 Tony Awards® for their work. Choreography is by Liza Gennaro, who has incorporated selections from her father Peter Gennaro’s 1977 Tony Award®-winning choreography. The celebrated design team includes scenic design by Tony Award® winner Beowulf Boritt (Act One, The Scottsboro Boys, Rock of Ages), costume design by Costume Designer’s Guild Award winner Suzy Benzinger (Blue Jasmine, Movin’ Out, Miss Saigon), lighting design by Tony Award® winner Ken Billington (Chicago, Annie, White Christmas) and sound design by Tony Award® nominee Peter Hylenski (Rocky, Bullets Over Broadway, Motown). The lovable mutt “Sandy” is once again trained by Tony Award® Honoree William Berloni (Annie, A Christmas Story, Legally Blonde). Musical supervision and additional orchestrations are by Keith Levenson (Annie, She Loves Me, Dreamgirls). Casting is by Joy Dewing CSA, Joy Dewing Casting (Soul Doctor, Wonderland). The tour is produced by TROIKA Entertainment, LLC. The production features a 25 member company: in the title role of Annie is Heidi Gray, an 11- year-old actress from the Augusta, GA area, making her tour debut. -

2019 Silent Auction List

September 22, 2019 ………………...... 10 am - 10:30 am S-1 2018 Broadway Flea Market & Grand Auction poster, signed by Ariana DeBose, Jay Armstrong Johnson, Chita Rivera and others S-2 True West opening night Playbill, signed by Paul Dano, Ethan Hawk and the company S-3 Jigsaw puzzle completed by Euan Morton backstage at Hamilton during performances, signed by Euan Morton S-4 "So Big/So Small" musical phrase from Dear Evan Hansen , handwritten and signed by Rachel Bay Jones, Benj Pasek and Justin Paul S-5 Mean Girls poster, signed by Erika Henningsen, Taylor Louderman, Ashley Park, Kate Rockwell, Barrett Wilbert Weed and the original company S-6 Williamstown Theatre Festival 1987 season poster, signed by Harry Groener, Christopher Reeve, Ann Reinking and others S-7 Love! Valour! Compassion! poster, signed by Stephen Bogardus, John Glover, John Benjamin Hickey, Nathan Lane, Joe Mantello, Terrence McNally and the company S-8 One-of-a-kind The Phantom of the Opera mask from the 30th anniversary celebration with the Council of Fashion Designers of America, designed by Christian Roth S-9 The Waverly Gallery Playbill, signed by Joan Allen, Michael Cera, Lucas Hedges, Elaine May and the company S-10 Pretty Woman poster, signed by Samantha Barks, Jason Danieley, Andy Karl, Orfeh and the company S-11 Rug used in the set of Aladdin , 103"x72" (1 of 3) Disney Theatricals requires the winner sign a release at checkout S-12 "Copacabana" musical phrase, handwritten and signed by Barry Manilow 10:30 am - 11 am S-13 2018 Red Bucket Follies poster and DVD, -

Television Academy Awards

2019 Primetime Emmy® Awards Ballot Outstanding Comedy Series A.P. Bio Abby's After Life American Housewife American Vandal Arrested Development Atypical Ballers Barry Better Things The Big Bang Theory The Bisexual Black Monday black-ish Bless This Mess Boomerang Broad City Brockmire Brooklyn Nine-Nine Camping Casual Catastrophe Champaign ILL Cobra Kai The Conners The Cool Kids Corporate Crashing Crazy Ex-Girlfriend Dead To Me Detroiters Easy Fam Fleabag Forever Fresh Off The Boat Friends From College Future Man Get Shorty GLOW The Goldbergs The Good Place Grace And Frankie grown-ish The Guest Book Happy! High Maintenance Huge In France I’m Sorry Insatiable Insecure It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia Jane The Virgin Kidding The Kids Are Alright The Kominsky Method Last Man Standing The Last O.G. Life In Pieces Loudermilk Lunatics Man With A Plan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Modern Family Mom Mr Inbetween Murphy Brown The Neighborhood No Activity Now Apocalypse On My Block One Day At A Time The Other Two PEN15 Queen America Ramy The Ranch Rel Russian Doll Sally4Ever Santa Clarita Diet Schitt's Creek Schooled Shameless She's Gotta Have It Shrill Sideswiped Single Parents SMILF Speechless Splitting Up Together Stan Against Evil Superstore Tacoma FD The Tick Trial & Error Turn Up Charlie Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt Veep Vida Wayne Weird City What We Do in the Shadows Will & Grace You Me Her You're the Worst Young Sheldon Younger End of Category Outstanding Drama Series The Affair All American American Gods American Horror Story: Apocalypse American Soul Arrow Berlin Station Better Call Saul Billions Black Lightning Black Summer The Blacklist Blindspot Blue Bloods Bodyguard The Bold Type Bosch Bull Chambers Charmed The Chi Chicago Fire Chicago Med Chicago P.D. -

Marvin Hamlisch

tHE iRA AND lEONORE gERSHWIN fUND IN THE lIBRARY OF cONGRESS AN EVENING WITH THE MUSIC OF MARVIN HAMLISCH Monday, October 19, 2015 ~ 8 pm Coolidge Auditorium Library of Congress, Thomas Jefferson Building The Ira and Leonore Gershwin Fund in the Library of Congress was established in 1992 by a bequest from Mrs. Gershwin to perpetuate the name and works of her husband, Ira, and his brother, George, and to provide support for worthy related music and literary projects. "LIKE" us at facebook.com/libraryofcongressperformingarts loc.gov/concerts Please request ASL and ADA accommodations five days in advance of the concert at 202-707-6362 or [email protected]. Latecomers will be seated at a time determined by the artists for each concert. Children must be at least seven years old for admittance to the concerts. Other events are open to all ages. • Please take note: Unauthorized use of photographic and sound recording equipment is strictly prohibited. Patrons are requested to turn off their cellular phones, alarm watches, and any other noise-making devices that would disrupt the performance. Reserved tickets not claimed by five minutes before the beginning of the event will be distributed to stand-by patrons. Please recycle your programs at the conclusion of the concert. The Library of Congress Coolidge Auditorium Monday, October 19, 2015 — 8 pm tHE iRA AND lEONORE gERSHWIN fUND IN THE lIBRARY OF cONGRESS AN EVENING WITH THE mUSIC OF MARVIN hAMLISCH WHITNEY BASHOR, VOCALIST | CAPATHIA JENKINS, VOCALIST LINDSAY MENDEZ, VOCALIST | BRYCE PINKHAM, VOCALIST -

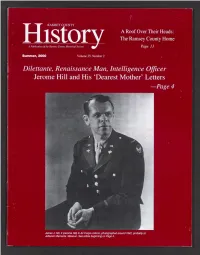

Jerome Hill and His 'Dearest Mother'

RAMSEY COUNTY A Roof Over Their Heads: The Ramsey County Home A Publication of the Ramsey County Historical Society Page 13 Summer, 2000 Volume 35, Number 2 Dilettante, Renaissance Man, Intelligence Officer Jerome Hill and His ‘Dearest Mother’ Letters —Page 4 Jam es J. Hill, Il (Jerome HUI) in Air Corps uniform, photographed around 1942, probably at Jefferson Barracks, Missouri. See article beginning on Page 4. RAMSEY COUNTY HISTORY Executive Director Priscilla Farnham Editor Virginia Brainard Kunz RAMSEY COUNTY Volume 35, Number 2 Summer, 2000 HISTORICAL SOCIETY BOARD OF DIRECTORS Laurie A. Zenner CONTENTS Chair Howard M. Guthmann 3 Letters President James Russell 4 Dilettante, Renaissance Man, Intelligence Officer First Vice President Jerome Hill and His World War II Letters from Anne Cowie Wilson Second Vice President France to His ‘Dearest Mother’ Richard A. Wilhoit G. Richard Slade Secretary Ronald J. Zweber 13 A Roof Over Their Heads Treasurer The History of the Old Ramsey County ‘Poor Farm’ W. Andrew Boss, Peter K. Butler, Charlotte H. Drake, Mark G. Eisenschenk, Joanne A. Englund, Pete Boulay Robert F. Garland, John M. Harens, Judith Frost Lewis, John M. Lindley, George A. Mairs, Mar 20 Plans for Preserving ‘Potters’ Field’— Heritage of the lene Marschall, Richard T. Murphy, Sr., Linda Owen, Marvin J. Pertzik, Vicenta D. Scarlett, Public Welfare System Glenn Wiessner. Robert C. Vogel EDITORIAL BOARD 22 Recounting the 1962 Recount John M. Lindley, chair; James B. Bell, Thomas H. Boyd, Thomas C. Buckley, Pat Hart, Virginia The Closest Race for Governor in Minnesota’s History Brainard Kunz, Thomas J. Kelley, Tom Mega, Laurie Murphy, Vicenta Scarlett, G. -

American Music Research Center Journal

AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER JOURNAL Volume 19 2010 Paul Laird, Guest Co-editor Graham Wood, Guest Co-editor Thomas L. Riis, Editor-in-Chief American Music Research Center College of Music University of Colorado Boulder THE AMERICAN MUSIC RESEARCH CENTER Thomas L. Riis, Director Laurie J. Sampsel, Curator Eric J. Harbeson, Archivist Sister Mary Dominic Ray, O.P. (1913–1994), Founder Karl Kroeger, Archivist Emeritus William Kearns, Senior Fellow Daniel Sher, Dean, College of Music William S. Farley, Research Assistant, 2009–2010 K. Dawn Grapes, Research Assistant, 2009–2011 EDITORIAL BOARD C. F. Alan Cass Kip Lornell Susan Cook Portia Maultsby Robert R. Fink Tom C. Owens William Kearns Katherine Preston Karl Kroeger Jessica Sternfeld Paul Laird Joanne Swenson-Eldridge Victoria Lindsay Levine Graham Wood The American Music Research Center Journal is published annually. Subscription rate is $25.00 per issue ($28.00 outside the U.S. and Canada). Please address all inquiries to Lisa Bailey, American Music Research Center, 288 UCB, University of Colorado, Boulder, CO 80309-0288. E-mail: [email protected] The American Music Research Center website address is www.amrccolorado.org ISSN 1058-3572 © 2010 by the Board of Regents of the University of Colorado INFORMATION FOR AUTHORS The American Music Research Center Journal is dedicated to publishing articles of general interest about American music, particularly in subject areas relevant to its collections. We welcome submission of articles and pro- posals from the scholarly community, ranging from 3,000 to 10,000 words (excluding notes). All articles should be addressed to Thomas L. Riis, College of Music, University of Colorado Boulder, 301 UCB, Boulder, CO 80309-0301. -

SMTA Catalog Complete

The Integrated Broadway Library Index including the complete works from 34 collections: sorted by musical HL The Singer's Musical Theatre Anthology (22 vols) A The Singer's Library of Musical Theatre (8 vols) TMTC The Teen's Musical Theatre Collection (2 vols) MTAT The Musical Theatre Anthology for Teens (2 vols) Publishers: HL = Hal Leonard; A = Alfred *denotes a song absent in the revised edition Pub Voice Vol Page Song Title Musical Title HL S 4 161 He Plays the Violin 1776 HL T 4 198 Mama, Look Sharp 1776 HL B 4 180 Molasses to Rum 1776 HL S 5 246 The Girl in 14G (not from a musical) HL Duet 1 96 A Man and A Woman 110 In The Shade HL B 5 146 Gonna Be Another Hot Day 110 in the Shade HL S 2 156 Is It Really Me? 110 in the Shade A S 1 32 Is It Really Me? 110 in the Shade HL S 4 117 Love, Don't Turn Away 110 in the Shade A S 1 22 Love, Don't Turn Away 110 in the Shade HL S 1 177 Old Maid 110 in the Shade HL S 2 150 Raunchy 110 in the Shade HL S 2 159 Simple Little Things 110 in the Shade A S 1 27 Simple Little Things 110 in the Shade HL S 5 194 Take Care of This House 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue A T 2 41 Dames 42nd Street HL B 5 98 Lullaby of Broadway 42nd Street A B 1 23 Lullaby of Broadway 42nd Street HL T 3 200 Coffee (In a Cardboard Cup) 70, Girls, 70 HL Mezz 1 78 Dance: Ten, Looks: Three A Chorus Line HL T 4 30 I Can Do That A Chorus Line HL YW MTAT 120 Nothing A Chorus Line HL Mezz 3 68 Nothing A Chorus Line HL Mezz 4 70 The Music and the Mirror A Chorus Line HL Mezz 2 64 What I Did for Love A Chorus Line HL T 4 42 One More Beautiful -

Page 01.Indd

YOUR HOMETOWN NEWSPAPER SINCE 1911 Thursday, July 1, 2021 109th Year - No. 42 thezephyrhillsnewsonline.com 50¢ Main Street new director is A Look Back ... welcomed by local offi cials JULY 1, 2004 Wealth of Health New series harkens back to Here are several ideas on how to safely unwind days gone by. Let’s look without health risks. at the above date ➤ 8 BY STEVE LEE News Reporter This week’s Look Back, the eighth in our series, brings us a bit closer in time than in previous editions. We welcome readers to 2004 when a NASA spacecraft landed on Mars, Mark Zuckerberg created Facebook, former President Ronald Reagan passed away and the Tampa Bay Lightning won its fi rst Stanley Cup. Weather Closer to home, in the little niche of the world called east Pasco, The Zephyrhills News The recent trend of primarily brought plenty of local news to the community wet weather will continue and outlying areas including Dade City, for the most part with Wesley Chapel and San Antonio. scattered showers in the The centerpiece photo on the front page forecast for fi ve of the next featured local fi refi ghters, led by Zephyrhills seven days. Temperatures Captain Kerry Barnett, demonstrating how to are expected to be seasonal put out a car fi re. Deal Auto Salvage provided with mostly 90s in the days the automobile and use of the lot for the and 70s in the evenings. training exercise. ➤ 3 Concerns about increased traffi c led city Faith Wilson, the new director for Main Street Zephyrhills, goes over the new web site with members of city council during Monday night’s council members to make changes for trucks Community Redevlopment Agency meeting. -

BROOKS ATKINSON THEATER (Originally Mansfield Theater), 256-262 West 47Th Street, Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 4, 1987; Designation List 194 LP-1311 BROOKS ATKINSON THEATER (originally Mansfield Theater), 256-262 West 47th Street, Manhattan. Built 1925-26; architect Herbert J. Krapp. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1018, Lot 57. On June 14 and 15, 1982, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Brooks Atkinson Theater and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (I tern No. 7). The hearing was continued to October 19, 1982. Both hearings had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Eighty witnesses spoke or had statements read into the record in favor of designation. Two witnesses spoke in opposition to designation. The owner, with his representatives, appeared at the hearing, and indicated that he had not formulated an opinion regarding designation. The Commission has · received many letters and other expressions of support in favor of this designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS The Brooks Atkinson Theater survives today as one of the historic theaters that symbolize American theater for both New York and the nation. Built during the mid-1920s, the Brooks Atkinson was among the half-dozen theaters constructed by the Chanin Organization, to the designs of Herbert J. Krapp, that typified the development of the Times Square/Broadway theater district. Founded by Irwin S. Chanin, the Chanin organization was a major construction company in New York. During the 1920s, Chanin branched out into the building of theaters, and helped create much of the ambience of the heart of the theater district.