Can David Wagoner, Poet of Nature and the Environment, Qualify As Eco-Poet?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

F68 Binder3.Pdf

EDITOR y David Wagoner EDITORIAL CONSULTANTS POETRY A ‘LNORTHWEST VOLUME NINE NUMBER THREE AUTUMN 1968 EUGENE RUGGLES Five Poems . JAMES M. KEEGAN Two Poems STUART SILVERIVIAN Two Poems HAROLD‘ WITT Two Poems 10 WILL STUBBS Three Poems 12 CHARLES BAXTER Two Poems 15 ‘ HELEN SORRELLS Moiave . 17 DANIEL LUSK Penny Candy and Birds 18 /\l.|iX‘ANDER KUO Drowning in Winter . 20 Ml(.'ll/\EL S. HARPER. Three Poems . 22 I/\Ni'I IIAYMAN The Hog Remembers 25 .‘a|."w"l'l~IR, MADELINE DEFREES Two Poems . 26 [I )I IN M()()RI§ Squall 27 [I H IN (.|{|‘il(iI[TON 3-In-|<in(| llm Panes 28 HAI If ( lI/\'l'l''IIiLI) I nmmmucy Room . 29 IHM W’/\\'f\rI/\N lualm Monday 1967: Driving Southwarcl 30 HAROLD BOND Two Poems 32 BARRY GOLDENSOHN A Woman and Silence . 34 HENRY CARLILE Grcmdmother . 35 ADRIANNE MARCUS Two Poems 37 HARLEY ELLIOTT Mass Production . 39 DONNA BROOK Two Poems 40 PETER WILD Three Poems 42 RALPH ROBIN 44 Excu I potion STANLEY RADHUBER The Road Bock 45 ROBIN MORGAN The Father . 46 PETER COOLEY The Rooms . 47 JOHN JUDSON Morgan's Comes . 48 STEVEN FOSTER Two Poems 49 JOAN LABOMBARD Ohio: 1925 5| ROBERT HERSHON Two Poems . 5') Change of Address Notify us promptly when you change your mailin;-, znlrhu . Send both the old address and the new—and the Z11’ ( ‘mlr nu-ml». Allow us at least six weeks for processing: tlw rlun,-. POETRY NORTHWEST AUTUMN 1968 I Eugene Ruggles Five Poems VVALKING BENEATH THE GROUND Something has died and I walk a so thick and black night heavy in it’s to walk beneaththe ground. -

SPRING 1977 David Wagoner GWEN HEAD Four Poems

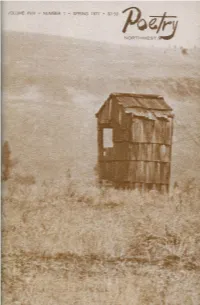

C ~ C. P POET RY + NORTHWEST VOLUME EIGHTEEN NUMBER ONE EDITOR SPRING 1977 David Wagoner GWEN HEAD Four Poems . JAY MEEK EDITORIAL CONSULTANTS Two Poems.. .. .. ... ... 10 Nelson Bentley, William H. Matchett ROB SWIGART Bone Poem.. .. ., ... ... JOAN SWIFT COVER DESIGN Plankton. 16 Allen Auvil DOUGLAS CRASE Three Poems.. 17 J OHN HOLBRO O K Coverfrom a photograph of the entrance to Starting with What I Have at Home 19 a dude ranch near Cle Elum, Wash. MARK McCLOSKEY Two Poems.. .. .. ... ... 20 D IANA 0 H E H I R F our Poems. GARY SOTO T he Leaves. 24 BOARD OF ADVISERS ROSS TALARICO Leonie Adams, Robert Fitzgerald, Robert B. Heilman, T wo Poems. Stanley Kunitz,Jackson Mathews, Arnold Stein WILLIAM MEISSNER D eath of the Track Star. 28 T. R. JAHNS T he Gift. 29 I'OETRY NORTHWEST S P RING 1977 VOL UME XVIII, NUMBER 1 DEBORA GREGER Published quarterly by the University of Washington. Subscriptions md manu Two Poems.. .. .. ... .. .. 30 scripts shonld be sent to Poetry Northwest, 4045 Brooklyn Avenue NE, Univer LINDA ALLARDT sity of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98105. Not responsible for unsolicited T wo Poems. manuscripts; all submissions must be accompanied by a stamped self-addressed 31 envelope. Subscription rates: U.S., $5.00 per year, single copies $1.50; Canada JOSEPH DI PRISCO $6.00 per year, single copies $1.75. T he Restaurant. ROBERT HERSHON © 1977 by the University of Washington We Never Ask Them Questions .. Distributed by B. DeBoer, 188 High Street, Nutley, N.J. 07110; and in the West KITA SHANTIRIS by L-S Distributors, 1161 Post Street, San Francisco, Calif. -

Winter 1970-71

NORTHWES POETRY g+ NORTHWEST VOLUME ELEVEN NUMBER FOUR EDITOR David Wagoner WINTER 1970-71 EDITORIAL CONSULTANTS RICK DeMARINIS Nelson Bentley, William H. Matchett Furnishing Your House VINCENT B. SHERRY Three Poems CovER DEsIGN GIBBONS RUARK Ann Downs Two Poems WESLEY McNAIR Don Greenwood's Picture in an Insurance Magazine 10 PETER WILD Coyanosa . ALBERT GOLDBARTH One of Wooser's Stories . 13 Cover: Ttingit shaman's charm, Beaver andDragonfly. PETER H. SEARS How Do You Really Do . 15 JOHN TAYLOR Through Channels . 16 VASSILIS ZAMBARAS BOARD OF ADVISERS Two Poems 16 Leonie Adams, Robert Fitzgerald, Robert B. Heilman, RICHARD DANKLEFF Two Poems 17 Stanley Kunitz, Jackson Mathews, Arnold Stein ROBIN JOHNSON The Dark Bells . 19 LINDA ALLARDT POETRY NORTHWEST W I N TER 1970 — 71 VOLUME XI, NUMBER 4 Angry in Spring 20 DAVID ZAISS Published quarterly by the University of Washington. Subscriptions and mant' Two Poems 20 scripts should b e sent to Po e try N o r t hwest, Parrington H a l l, U n i v ersity of DAVID LUNDE Washington, Seattle, Washington 98105. Not responsible for unsolicited manu Space scripts; all submissions must. be accompanied by a s t amped,self .addresse ddressed envelope. Subscription rate, $3.50 per year; single copies, $1.00 DOUGLAS FLAHERTY o1971 by the University of Washington Back Trailing Distributed by B . D e Boer, 188 High Street, Nutley, N.j . 07110; and tn Calif. 94102. West by L-S Distributors, 55> McAllister Street, San Francisco, Calif. HAROLD WITT Nancy Van Deusen P O E T R Y N O R T H W E S T GARY GILDNER WINTER 1970 — 71 Two Poems 26 WARREN WOESSNER Two Poems 28 JOHN ALLMAN The Lovers 29 PATRICIA GOEDICKE Rick DeMarieis All Morning I Have Seen the Whitening 30 CAROLYN STOLOFF FURNISHING YOUR HOUSE Two Poems 30 MARK HALLIDAY It isn't easy filling your house. -

Last Updated 01/14/2021

UAPC Broadside Holdings | 1 of 115 University of Arizona Poetry Center Broadside Holdings - Last Updated 01/14/2021 This computer-generated list is accurate to the best of our knowledge, but may contain some formatting issues and/or inaccuracies. Thank you for your understanding. Author Title / Author Publisher Country music is cool poem / Cory Aaland, Cory. Aaland. Tucson, Ariz. : K Li, [2013] Waldron Island Brooding Heron Press Aaron, Howard. The Side Yard. 1988. Academy of American Poets Academy of American national poetry month April 2013 New York : Academy of American Poets, Poets. [poster]. 2013. Ace, Samuel, February / Samuel Ace. Tucson : Edge, 2009. "Top Withens" and "Excerpt from What Makes All Groups? The Adair-Hodges, Erin. Loom." Tucson University of Arizona 2006. Sea in Two Poems for Courage and Adnan, Etel. Change. Silver Spring Pyramid Atlantic 2006. Don't call alligator long-mouth till [Great Britain] : London Arts Board, Agard, John, you cross river / John Agard. [1997?] Agha, Shahid Ali, "Stationery" Wesleyan University Press n.d. [Paradise Valley, Ariz.] : [Mummy Agha, Shahid Ali, A pastoral / Agha Shahid Ali. Mountain Press], [1993] Agha, Shahid Ali, "A Rehearsal of Loss" Tucson Tucson Poetry Festival 1992. Burning Deck Postcards: The fourth Ahern, Tom. ten. Providence, R.I., Burning Deck Press, 1978. Ahmed, Zubair. Shaving / Zubair Ahmed. [Portland, Ore.] : Tavern Books, 2011. On being one-half Japanese one- eighth Choctaw one-fourth Black & Ai, one-sixteenth Irish / Ai. Portland, Oregon : Tavern Books, 2018. [Paradise Valley, Ariz.] : Mummy Mountain Ai, The journalist / Ai. Press, [199-?] [Paradise Valley, Ariz.] : Mummy Mountain Ai, Cruelty / Ai. Press, [199-?] Mouth of the Columbia : poem / by Akers, Deborah. -

****************************W********************************** * Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made * * from the Original Document

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 432 780 CS 216 827 AUTHOR Somers, Albert. B. TITLE Teaching Poetry in High School. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-5289-9 PUB DATE 1999-00-00 NOTE 230p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 52899-0015: $14.95 members, $19.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides - Classroom - Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Class Activities; *English Instruction; High Schools; Internet; *Poetry; *Poets; Student Evaluation; Teaching Methods IDENTIFIERS Alternative Assessment ABSTRACT Suggesting that the teaching of poetry must be engaging as well as challenging, this book presents practical approaches, guidelines, activities, and scenarios for teaching poetry in high school. It offers 40 complete poems; a discussion of assessment issues (including authentic assessment); poetry across the curriculum; and addresses and annotations for over 30 websites on poetry. Chapters in the book are (1) Poetry in America; (2) Poetry in the Schools;(3) Selecting Poetry to Teach;(4) Contemporary Poets in the Classroom;(5) Approaching Poetry;(6) Responding to Poetry by Talking;(7) Responding to Poetry by Performing;(8) Poetry and Writing; (9) Teaching Form and Technique;(10) Assessing the Teaching and Learning of Poetry;(11) Teaching Poetry across the Curriculum; and (12) Poetry and the Internet. Appendixes contain lists of approximately 100 anthologies of poetry, 12 reference works, approximately 50 selected mediaresources, 4 selected journals, and 6 selected awards honoring American poets. (RS) *********************************************w********************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made * * from the original document. -

Building a Core Poetry Collection 811: American Poetry

KIT: BUILDING A CORE POETRY COLLECTION 811: AMERICAN POETRY Created for the Library as Incubator Project by Erinn Batykefer with many thanks to Professor Jesse Lee Kercheval of the UW-Madison Creative Writing Department, whose “Poetry Life List,” was the inspiration for this Kit. Collecting poetry can be daunting because there are so few mainstream review outlets that cover the genre in any meaningful way. There are ways around this, though, and none require a crash course in every school of American Poetry in living memory—a good thing for time-crunched librarians! This kit includes a long list of important American Poets that anyone interested in the genre will want to be familiar with, plus some important titles for each—a core collection. It begins by noting some key techniques and resources that will help you to build on this core collection and grow a wonderful 811 section year by year. CORE MAGAZINES Two suggestions for craft-based magazines: • Poets and Writers • AWP Writer’s Chronicle If your patrons are interested in poetry journals (also known as little magazines), you might subscribe to a few that represent different regions of the country / schools. Be forewarned: yearly subscriptions to little mags are expensive and folks are very opinionated about which are ‘good’; however, they often review new titles, which is a bonus, and they often have robust webpages and online content (including more reviews). A selection of heavy hitters: • Poetry Magazine (Chicago) | www.poetryfoundation.org/poetrymagazine o If you can only subscribe -

Short Vita for David Wagoner Born 1926 in Massillon, Ohio Grew up In

Short vita for David Wagoner Born 1926 in Massillon, Ohio Grew up in Whiting, Indiana B.A. in English from Penn State Univ., 1947 M.A. in English from Indiana Univ., 1949 Instructor at DePauw Univ. , 1949-50 Instructor at Penn State Univ., 1950-53 Instructor at Univ. of Washington, 1954-55 Assistant professor at Univ. of Washington, 1955-59 Associate professor at Univ. of Washington, 1959-1966 Professor at Univ. of Washington, 1966-2002 Professor Emeritus at Univ. of Washington, 2002-present Editor of POETRY NORTHWEST, 1966-2002 Literary adviser to the Seattle Repertory Theater, 1963-72 Editor of the Princeton Univ. Press Poetry Series, 1982-84 Editor of the Univ. of Missouri Press Breakthrough Poetry Series, 1984-85 Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets, 1978-2000 Woodrow Wilson Fellow, 2008-present Books of poems: DRY SUN, DRY WIND, Indiana Univ. Press, 1952 A PLACE TO STAND, Indiana Univ. Press , 1958 THE NESTING GROUND, Indiana Univ. Press, 1963 STAYING ALIVE, Indiana Univ. Press, 1966 NEW AND SELECTED POEMS, Indiana Univ. Press, 1969 RIVERBED, Indiana Univ. Press, 1972 WORKING AGAINST TIME, London: Rapp & Whiting, Ltd., 1973 SLEEPING IN THE WOODS, Indiana Univ. Press, 1974 COLLECTED POEMS, Indiana Univ. Press, 1976 WHO SHALL BE THE SUN? Indiana Univ. Press, 1978 IN BROKEN COUNTRY, Atlantic-Little, Brown, 1979 LANDFALL, Atlantic-Little, Brown, 1981 FIRST LIGHT, Atlantic-Little, Brown, 1983 THROUGH THE FOREST: New and Selected Poems, 1977-87, Atlantic Monthly Press, 1987 WALT WHITMAN BATHING, Univ. of Illinois Press, 1996 TRAVELING LIGHT: Collected and New Poems, Univ. of Illinois Press, 1999 THE HOUSE OF SONG, Univ. -

Western Reader

The Portable WESTERN READER Edited and with an Introduction by WILLIAM KITTREDGE / .••: -•• * PENGUIN BOOKS '. CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii INTRODUCTION: "WEST OF YOUR TOWN: ANOTHER COUNTRY" by William Kittredge xv PART ONE: ANCIENT STORIES Introduction 1 Washington Matthews "House Made of the Dawn" (Navajo night chant) 2 A. L. Kroeber "The Woman and the Horse," from Gros Ventre Myths and Tales 6 Catharine McClellan "The Girl Who Married the Bear" 7 Jarold Ramsey "Coyote and Eagle Go to the Land of the Dead" 14 C. C. Uhlenbeck "How the Ancient Peigans Lived" (Blackfeet tale) 17 James Welch from Fools Crow 23 James Mooney from The Ghost-Dance Religion and the Sioux Outbreak of 1890 39 Linda Hogan from Mean Spirit 40 John Graves "The Last Running" 47 Louise Erdrich "Fleur" 61 Joy Harjo "Deer Dancer" 74 x Contents PART TWO: TRANSCENDING THE WESTERN Introduction Walt Whitman "Song of the Redwood-Tree" from Leaves of Grass e. e. cummings "Buffalo Bill's" D. H. Lawrence from "Fenimore Cooper's Leatherstocking Tales," in Studies in Classic American Literature Meriwether Lewis and William Clark from the Journals A. B. Guthrie Jr. from The Big Sky Teddy Blue Abbott from We Pointed Them North: Recollections of a Cowpuncher O. E. Rolvaag from Giants in the Earth Elinore Rupert Stewart from Letters of a Woman Homesteader Wallace Stegner "Carrion Spring," from Wolf Willow Mari Sandoz from Old Jules Dorothy M. Johnson "The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance" • Jack London "A Raid on the Oyster Pirates" John Steinbeck "The Squatters' Camps," from The Harvest Gypsies Robinson Jeffers "Eagle Valor, Chicken Mind" Ernest Hemingway "The Clark's Fork Valley, Wyoming" Theodore Roethke "All Morning" . -

Colors of a Different Horse: Rethinking Creative Writing Theory and Pedagogy

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 366 967 CS 214 218 AUT7OR Bishop, Wendy, Ed.; Ostrom, Hans, Ed. TITLE Colors of a Different Horse: Rethinking Creative Writing Theory and Pedagogy. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, REPORT NO ISBN-0-8141-0716-8 PUB DATE 94 NOTE 346p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 07168-3050; $16.95 members, $22.95 nonmembers). PUB TYPE Collected Works General (020) Viewpoints (Opinion/Position Papers, Essays, etc.)(120) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Classroom Environment; *Creative Writing; Higher Education; *Instructional Effectiveness; Instructional Innovation; Professional Development; *Rhetoric; Theory Practice Relationship; *Writing Laboratories; *Writing Teachers IDENTIFIERS *Composition Theory; Professional Concerns; Voice (Rhetoric);Writing Contexts ABSTRACT In considering exactly what takes place in creative writing classrooms, this collection of 22essays reexamines the profession of writing teacher and ponders why certainpractices and contexts prevail. The essays and their authorsare as follows: "Introduction: Of Radishes and Shadows, Theory and Pedagogy" (Hans Ostrom); (1) "The Workshop and Its Discontents" (FrancoisCamoin); (2) "Reflections on the Teaching of Creative Writing: A Correspondence" (Eugene Garber and Jan Ramjerdi);(3) "The Body of My Work Is Not Just a Metaphor" (Lynn Domina);(4) "Life in the Trenches: Perspectives from Five Writing Programs" (AnnTurkle and others);(5) "Theory, Creative Writing, and theImpertinence of History" (R. M. Berry);(6) "Teaching Creative Writing if the Shoe Fits" (Katharine Haake);(7) "Pedagogy in Penumbra: Teaching, Writing, and Feminism in the Fiction Workshop" (GayleElliott); (8) "Literary Theory and the Writer" (Jay Parini);(9) "Creativity Research and Classroom Practice" (Linda Sarbo and JosephM. -

Contributors, Books Received, Magazines Received, Back Issues, Advertisements, Back Cover

CutBank Volume 1 Issue 13 CutBank 13 Article 44 Fall 1979 Contributors, Books Received, Magazines Received, Back Issues, Advertisements, Back Cover Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cutbank Part of the Creative Writing Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation (1979) "Contributors, Books Received, Magazines Received, Back Issues, Advertisements, Back Cover," CutBank: Vol. 1 : Iss. 13 , Article 44. Available at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/cutbank/vol1/iss13/44 This Back Matter is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in CutBank by an authorized editor of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CONTRIBUTORS RALPH BEER operates a fourth-generation cattle ranch at Jackson Creek, Montana. He is completing his MFA at the University of Montana. LINDA BIERDS lives in Seattle, Washington. She has poems forthcoming in Concerning Poetry, Poetry Now, and elsewhere. KATHY CALLAWAY, a former editor ofC utB ank with an MFA from the University of Montana, is now living and working (we hope) in New York City. She is dearly missed. PATRICIA CLARK is from Tacoma, Washington. She is in the MFA program at the University of Montana and teaches composition. CARL CLATTERBUCK lives in Missoula, Montana. He has recently published in Cavalier. SUSAN DAVIS grew up in Slough House, California and is a graduate of Sacramento State College. STEPHEN DUNN is currently living in New Jersey. His books includeLooking for Holes in the Ceiling and Of Lust and Good Usage. -

University of Arizona Poetry Center Broadside Holdings Last Updated 01/15/2016

UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA POETRY CENTER BROADSIDE HOLDINGS LAST UPDATED 01/15/2016 This computer-generated list is accurate to the best of our knowledge, but may contain some formatting issues and/or inaccuracies. Thank you for your understanding. AUTHOR TITLE PUBLISHER Country music is cool poem / Cory Aaland, Cory. Aaland. Tucson, Ariz. : K. Li, [2013] Waldron Island Brooding Heron Aaron, Howard. The Side Yard. Press 1988. Academy of American Poets national poetry month April 2013 New York : Academy of Academy of American Poets. [poster]. American Poets, 2013. Ace, Samuel. February / Samuel Ace. Tucson : Edge, 2009. Top Withens and Excerpt from What Makes All Groups? The Tucson University of Arizona Adair-Hodges, Erin. Loom. 2006. Sea in Two Poems for Courage and Silver Spring Pyramid Atlantic Adnan, Etel. Change. 2006. Don't call alligator long-mouth till [Great Britain] : London Arts Agard, John, 1949- you cross river / John Agard. Board, [1997?] Tucson Tucson Poetry Festival Agha, Shahid Ali, 1949-2001. A Rehearsal of Loss 1992. Agha, Shahid Ali, 1949-2001. Stationery Wesleyan University Press n.d. [Paradise Valley, Ariz.] : [Mummy Mountain Press], Agha, Shahid Ali, 1949-2001. A pastoral / Agha Shahid Ali. [1993] [Portland, Ore.] : Tavern Books, Ahmed, Zubair. Shaving / Zubair Ahmed. 2011. [Paradise Valley, Ariz.] : [Mummy Mountain Press], [199- Ai, 1947-2010. Cruelty / Ai. ?] [Paradise Valley, Ariz.] : [Mummy Mountain Press], [199- Ai, 1947-2010. The journalist / Ai. ?] Mouth of the Columbia : poem / by [Portland, Oregon] : Airlie Press, Akers, Deborah. Deborah Akers. 2015. Alexander, Charles, 1954- Create Culture. Tucson Chax Press 1993. Two poems / Christopher W. [Buffalo, N.Y.] : Cuneiform Alexander, Christopher W. -

Northwest Collection Creators List.Pdf

Northwest Collection Western Washington University Libraries List of Northwest creators (literary authors, artists, filmmakers, etc.) represented in collection Prepared in October 2019 by Jessica Mlotkowski and Casey Mullin Last updated: September 2021 Contents Alphabetical List .............................................................................................................................. 1 WWU Alumni ................................................................................................................................ 65 WWU Faculty ................................................................................................................................ 66 Creators of Color ........................................................................................................................... 67 Indigenous Persons ....................................................................................................................... 68 Alphabetical List Hazard Adams Literary Author Locale: Washington Biography: Hazard Adams (born 1923) is a literary scholar and novelist from Seattle, Washington. He is a professor emeritus at the University of Washington. William L. Adams Literary Author (Playwright) Locale: Oregon Biography: William L. Adams (1821-1906) was a playwright who lived in Oregon. His play, "Strategems, and Spoils, A Melodrame in Five Acts" was published in The Oregonian in 1952. Sherman Alexie Literary Author; Filmmaker Locale: Washington Biography: Sherman Alexie (born 1966) is a Spokane-Coeur