Copyright by Paul Joseph Erickson 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sociology at the London School of Economics and Political Science, 1904–2015 Christopher T

Sociology at the London School of Economics and Political Science, 1904–2015 Christopher T. Husbands Sociology at the London School of Economics and Political Science, 1904–2015 Sound and Fury Christopher T. Husbands Emeritus Reader in Sociology London School of Economics and Political Science London, UK Additional material to this book can be downloaded from http://extras.springer.com. ISBN 978-3-319-89449-2 ISBN 978-3-319-89450-8 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-89450-8 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018950069 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2019 This work is subject to copyright. All rights are solely and exclusively licensed by the Publisher, whether the whole or part of the material is concerned, specifically the rights of translation, reprinting, reuse of illustrations, recitation, broadcasting, reproduction on microfilms or in any other physical way, and trans- mission or information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now known or hereafter developed. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. Neither the publisher nor the authors or the editors give a warranty, express or implied, with respect to the material contained herein or for any errors or omissions that may have been made. -

U DPC Papers of Philip Corrigan Relating 1919-1973 to the London School of Economics

Hull History Centre: Papers of Philip Corrigan relating to the London School of Economics U DPC Papers of Philip Corrigan relating 1919-1973 to the London School of Economics Historical background: Philip Corrigan? The London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) is a specialist social science university. It was founded in 1894 by Beatrice and Sidney Webb. Custodial History: Donated by Philip Corrigan, Department of Sociology and Social Administration, Durham University, October 1974 Description: Material about the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) including files relating to the history of the institution, and miscellaneous files referring to accounts, links with other countries, particularly Southern Rhodesia, and aspects of student militancy and student unrest. Arrangement: U DPC/1-8 Materials (mainly photocopies) for a history of the London School of Economics and Political Science, 1919- 1973 U DPC/9-14 Miscellaneous files relating to LSE and higher education, 1966-1973 Extent: 0.5 linear metres Access Conditions: Access will be given to any accredited reader page 1 of 8 Hull History Centre: Papers of Philip Corrigan relating to the London School of Economics U DPC/1 File. 'General; foundation; the Webbs' containing the 1919-1970 following items relating to the London School of Economics and Political Science: (a) Booklist and notes (4pp.). No date (b) 'The London School of Economics and Political Science' by D. Mitrany ('Clare Market Review Series', no.1, 1919) (c) Memorandum and Articles of Association of the LSE, dated 1901, reprinted 1923. (d) 'An Historical Note' by Graham Wallas ('Handbook of LSE Students' Union', 1925, pp.11-13) (e) 'Freedom in Soviet Russia' by Sidney Webb ('Contemporary Review', January 1933, pp.11-21) (f) 'The Beginnings of the LSE'' by Max Beer ('Fifty Years of International Socialism', 1935, pp.81-88) (g) 'Graduate Organisations in the University of London' by O.S. -

GERMAN IMMIGRANTS, AFRICAN AMERICANS, and the RECONSTRUCTION of CITIZENSHIP, 1865-1877 DISSERTATION Presented In

NEW CITIZENS: GERMAN IMMIGRANTS, AFRICAN AMERICANS, AND THE RECONSTRUCTION OF CITIZENSHIP, 1865-1877 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alison Clark Efford, M.A. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2008 Doctoral Examination Committee: Professor John L. Brooke, Adviser Approved by Professor Mitchell Snay ____________________________ Adviser Professor Michael L. Benedict Department of History Graduate Program Professor Kevin Boyle ABSTRACT This work explores how German immigrants influenced the reshaping of American citizenship following the Civil War and emancipation. It takes a new approach to old questions: How did African American men achieve citizenship rights under the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments? Why were those rights only inconsistently protected for over a century? German Americans had a distinctive effect on the outcome of Reconstruction because they contributed a significant number of votes to the ruling Republican Party, they remained sensitive to European events, and most of all, they were acutely conscious of their own status as new American citizens. Drawing on the rich yet largely untapped supply of German-language periodicals and correspondence in Missouri, Ohio, and Washington, D.C., I recover the debate over citizenship within the German-American public sphere and evaluate its national ramifications. Partisan, religious, and class differences colored how immigrants approached African American rights. Yet for all the divisions among German Americans, their collective response to the Revolutions of 1848 and the Franco-Prussian War and German unification in 1870 and 1871 left its mark on the opportunities and disappointments of Reconstruction. -

The Chemistry Club a Number of Interesting Movies Were Enjoyed by the Chemistr Y Club This Year

Hist The Chronicle Coll CHS of 1942 1942 Edited by the Students of Chelmsford High School 2 ~{ Chelmsford High School Foreword The grcalest hope for Lh<' cider comes f rorn l h<' spiril of 1\mcrirnn youth. E xcmplilit>cl hy the cha r aclcristics of engerne%. f rnnk,wss. amhilion. inili,lli\·c'. and faith. il is one of the uplil'ling factor- of 01 1r li\'CS. \ \ 'iLhoul it " ·e could ,, <'II question th<' f1 1Lurc. \ \ 'ith il we rnusl ha\'C Lh e assurallce of their spirit. \ Ve hope you\\ ill nlld in the f oll o,, ing page:- some incli cnlion of your pasl belief in our young people as well as sornP pncouragcmenl for the rnnlinualion of your faiLh. The Chronicle of 1942 ~ 3 CONTENTS Foreword 2 Con lent 3 ·I 5 Ceo. ' . \\' righl 7 Lucian 11. 13urns 9 r undi y 11 13oard of l:cl ilors . Ser I iors U11dcrgrnd1rnlcs 37 .l11 nior Class 39 Sopho111ore Cb ss ,JO F reshma11 C lass 4 1 S port s 43 /\ct i,·ilies I lumor 59 Autographs 66 Chelmsford High School T o find Llw good in llE'. I've learned lo Lum T o LhosE' \\'ilh w hom my da ily lol is rasl. \ \/hose grncious h111n11n kindness ho lds me fast. Throughout the ycnr I w a nl to learn. T ho1 1gh war may rage and nations overlum. Those deep simplirilies Lhat li\'C and lasl. To M. RIT !\ RY J\N vV e dedicate our yearbook in gra te/ul recognition o/ her genial manner. -

The Historical Novel” an Audio Program from This Goodly Land: Alabama’S Literary Landscape

Supplemental Materials for “The Historical Novel” An Audio Program from This Goodly Land: Alabama’s Literary Landscape Program Description Interviewer Maiben Beard and Dr. Bert Hitchcock, Professor emeritus, of the Auburn University Department of English discuss the historical novel. Reading List Overviews and Bibliographies • Butterfield, Herbert. The Historical Novel: An Essay. Cambridge, Eng.: The University Press, 1924. Rpt. Folcroft, Penn.: Folcroft Library Editions, 1971. Rpt. Norwood, Penn.: Norwood Editions, 1975. • Carnes, Mark C., ed. Novel History: Historians and Novelists Confront America’s Past (and Each Other). New York: Simon & Schuster, 2001. • Coffey, Rosemary K., and Elizabeth F. Howard. America as Story: Historical Fiction for Middle and Secondary Schools. Chicago: American Library Association, 1997. • Dekker, George. The American Historical Romance. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1987. • Dickinson, A. T. American Historical Fiction. New York: Scarecrow Press, 1958. Rpt. New York: Scarecrow Press, 1963. • Henderson, Harry B. Versions of the Past: The Historical Imagination in American Fiction. New York: Oxford University Press, 1974. • Holman, C. Hugh. The Immoderate Past: The Southern Writer and History. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1977. • Leisy, Earnest E. The American Historical Novel. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1950. • Lukács, Georg [György]. The Historical Novel. Trans. Hannah and Stanley Mitchell. London: Merlin Press, 1962. • Matthews, Brander. The Historical Novel and Other Essays. New York: C. Scribner’s Sons, 1901. [An online version of The Historical Novel and Other Essays is available from Google Book Search at http://books.google.com/books?id=wA1bAAAAMAAJ.] • VanMeter, Vandelia L. America in Historical Fiction: A Bibliographic Guide. Englewood, Colo.: Libraries Unlimited, 1997. -

The Republican Journal: Vol. 84, No. 39

The Republican Joitrnai ' 7rtix>n7b4 BELFAST, MAINE. THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 26, 1912. NUMBER 7i«T~ lournal. Fred vs oif Today’s Rackliff F p'"' supreme Judicial Court. Flagg. Defaulted and E H vs Nellie R Goodwin. continued for Goodwin Libt, Conte"'* judgment. Knowlton; Johnson OBITUARY. [L.ard of Trade Supreme Libby. PERSONAL. Judge George F. Hanson, of Calais, Charles B Eaton vs Fred Curtis. Non personalT Li TheSta , Obituary. .The Sec- suited! Alfred G Bolin Libt, vs Rebecca N Bolin. Cen- Presiding.; Knowlton; Brown. Jennie S., widow of the late G. Tib- J. W. Cavalry..Jackson Libby. Henry Manson, Esq., of Pittsfield was a busi- f J“fl?!,De Personal. C W Waiter Whitehead went to ond «**'", ,,.ft Societies.. The Stephenson vs C H I betts, died Sept. 15th at her home in Rockland ness Boston grand jury reported Wednesday, return- Shuman, appealed Pearl Crockett vs L J Crockett. Sweetser & caller in Belfast Monday Friday. for a week's visit. The Murder of Capt Referred to Eben F Littlefield. after three months' illness. Her decline be- t Points ing eight indictments which were not made Brown; Buzzell Morse; Dunton & Morse. Mrs. Eugenia L. Cobbett of W L vs C E soon after Dover, N. H., is Freeman rr p?" Washington Whisperings.. Gray Mitchell and C B gan very the death of her O. is son |C- public until later in the week. They were a* Cook! J. Baum Safe & Lock Co vs Frank M Fair- husband, relatives in Roberts visiting his in gasno o... fumes. -The Man Who j visiting Belfast and vicinity. -

And Mention of American Indians

Updated: December 2020 CHAPTER 7 - THE AMERICAN BAHÁ'Í MAGAZINE January 1970: 1) NABOHR: Past, Present, and Future. The North American Bahá'í Office for Human Rights was established in January 1986. It is reported here that this office sponsored conferences for action on Human Rights in 20 leading cities and on a Canadian Reserve. There is a Photo here of presenter giving the address at the "American Indian and Human Rights" conference in Gallup, New Mexico. p. 3. 2) A program illustration entitled; "A World View" and it includes an Indian image. p. 7. February 1970: checked March 1970: 1) Bahá'í Education Conference Draws Overflow Attendance. More than 500 Bahá'ís from all over the U.S. come to this event. The only non Bahá'í speaker at the conference, Mrs. De Lee has a long record of civil rights activity in South Carolina. Her current project was to help 300 Indian school children in Dorchester County get into the public school. They were considered to be white until they tried to get their children in the public schools there. They were told they couldn't go to the public schools. A Freedom school was set up in an Indian community to teach Indian children and Mrs. Lee is still working towards getting them into the public school. pp. 1, 5. 2) News Briefs: The Minorities Teaching Committee of Albuquerque, NM held a unity Feast recently concurrent with the feast of Our Lady of Guadalupe, which is significant to the Mexican and American Indian populations of the area. -

Residents' Experience of High-Density Housing in London, 2018

Residents’ experience of high-density housing in London LSE London/LSE Cities report for the GLA Final report June 2018 By Kath Scanlon, Tim White and Fanny Blanc Table of contents 1. Rationale for the research and context ............................................................................... 2 2. Research questions and methodology ................................................................................ 4 2.1. Phases 1 and 2 ............................................................................................................. 4 2.2. Research questions ...................................................................................................... 4 2.3. Case study selection .................................................................................................... 4 2.4. Fieldwork .................................................................................................................... 6 2.5. Analysis and drafting .................................................................................................. 8 3. Existing knowledge ............................................................................................................ 9 3.1. Recent LSE research ................................................................................................... 9 3.2. Other recent research into density in London ........................................................... 10 3.3. What is good density? .............................................................................................. -

LSE Open Day

LSE Open Day Wednesday 3 April 2019 LSE Open Day Programme 1 World-class courses. Summer World-class city. School Welcome to LSE World-class experience. 2019 On behalf of all LSE’s staff and students, I would like to welcome you to our Open Day. We have created a schedule that gives you the opportunity to find out more about the subjects you are interested in, obtain information from LSE Summer School relevant departments and, perhaps most importantly, experience LSE’s unique atmosphere. This programme details the events and activities taking place during the Open Day, including times and locations. If you require any further information please ask one of our Student Ambassadors, who will be happy to assist you. These Ambassadors are also able to provide an insight into student life at LSE, so be sure to ask for their candid opinions! Please ensure that you (and your guest) register in the New Academic Building when you first arrive at the School. After registration you will be free to enjoy the many Open Day events taking place on campus. I do hope that you find your visit both informative and enjoyable, and that you will consider applying to LSE in the near future. Enjoy your day. Get a head start on your undergraduate studies Choose from over 100 17 June – inspiring courses taught by world-class LSE faculty Minouche Shafik 16 August Director, LSE 2019 Visit our stand for more information Library, LSE LIFE, Workspace 3 lse.ac.uk/summerschool 19_0057 A5 SS Advert-Offer-Holders-day_v5.indd 1 05/02/2019 10:32 2 LSE Open Day Programme Your Students’ Union Contents Welcome to LSE 1 Your Students’ Union 2 General events 4 and activities ASK AN AMBASSADOR General talks 5 We have a number of current LSE students working at the Open Day as Ambassadors. -

Laura Vaughan

Mapping From a rare map of yellow fever in eighteenth-century New York, to Charles Booth’s famous maps of poverty in nineteenth-century London, an Italian racial Laura Vaughan zoning map of early twentieth-century Asmara, to a map of wealth disparities in the banlieues of twenty-first-century Paris, Mapping Society traces the evolution of social cartography over the past two centuries. In this richly illustrated book, Laura Vaughan examines maps of ethnic or religious difference, poverty, and health Mapping inequalities, demonstrating how they not only serve as historical records of social enquiry, but also constitute inscriptions of social patterns that have been etched deeply on the surface of cities. Society The book covers themes such as the use of visual rhetoric to change public Society opinion, the evolution of sociology as an academic practice, changing attitudes to The Spatial Dimensions physical disorder, and the complexity of segregation as an urban phenomenon. While the focus is on historical maps, the narrative carries the discussion of the of Social Cartography spatial dimensions of social cartography forward to the present day, showing how disciplines such as public health, crime science, and urban planning, chart spatial data in their current practice. Containing examples of space syntax analysis alongside full-colour maps and photographs, this volume will appeal to all those interested in the long-term forces that shape how people live in cities. Laura Vaughan is Professor of Urban Form and Society at the Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL. In addition to her research into social cartography, she has Vaughan Laura written on many other critical aspects of urbanism today, including her previous book for UCL Press, Suburban Urbanities: Suburbs and the Life of the High Street. -

Roots and Routes Poetics at New College of California

Roots and Routes Poetics at New College of California Edited by Patrick James Dunagan Marina Lazzara Nicholas James Whittington Series in Creative Writing Studies Copyright © 2020 by the authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Suite 1200, Wilmington, Malaga, 29006 Delaware 19801 Spain United States Series in Creative Writing Studies Library of Congress Control Number: 2020935054 ISBN: 978-1-62273-800-7 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Cover design by Vernon Press. Cover image by Max Kirkeberg, diva.sfsu.edu/collections/kirkeberg/bundles/231645 All individual works herein are used with permission, copyright owned by their authors. Selections from "Basic Elements of Poetry: Lecture Notes from Robert Duncan Class at New College of California," Robert Duncan are © the Jess Collins Trust. -

1923 03 the Classes.Pdf

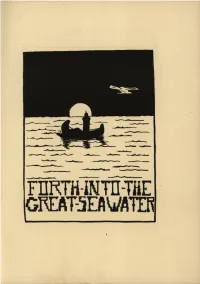

I Legends of the tribe, Forth-into-the-Great-Sea-Water LEGEND ONE T was autumn 1919 and the leaves of the maples were red and yellow along the streams. A tribe destined to be called Forth- into-the-Great-Sea-Water came to the camping ground of the Delawares. One of the three tribes greeting them looked upon them with scorn. The new tribe must prove itself worthy to dwell on the camping ground. The scornful ones inflicted many tortures to test their bravery. One dark night they painted black the faces of the helpless maidens. They gave them many unkinId words. They made them wear ivory rattles about their necks. But before many suns had set the strangers acquired merit in the eyes of the scornful. * And the friendly ones were proud of the progress of the young tribe. One time before the sun rose to drive away the mists of the night, the maidens of Forth-into-the-Great-Sea-Water stole forth from their wigwams. They raised their banner bearing the mystic figures, '23, to the top of a tall pole. The scornful ones became more displeased. They tried many times to lower the hated banner of their enemy. When they could not succeed their anger increased. At last they called friendly braves down the trail to help them. One night the maidens who wore the rattles dressed as braves. They bade the other tribes to the Great Lodge for a night of dancing. Although this new tribe had now acquired much wisdom, it needed counsel.