7 Defamation and the Grammar of Harsh Words1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Soziologie-Sociology in the German-Speaking

Soziologie – Sociology in the German-Speaking World Soziologie — Sociology in the German-Speaking World Special Issue Soziologische Revue 2020 Edited by Betina Hollstein, Rainer Greshoff, Uwe Schimank, and Anja Weiß ISBN 978-3-11-062333-8 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-062727-5 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-062351-2 ISSN 0343-4109 DOI https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110627275 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Library of Congress Control Number: 2020947720 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Betina Hollstein, Rainer Greshoff, Uwe Schimank, and Anja Weiß, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Contents ACompanion to German-Language Sociology 1 Culture 9 Uta Karstein and Monika Wohlrab-Sahr Demography and Aging 27 FrançoisHöpflinger EconomicSociology 39 AndreaMaurer Education and Socialization 53 Matthias Grundmann Environment 67 Anita Engels Europe 83 Monika Eigmüller Family and IntimateRelationships 99 Dirk Konietzka, Michael Feldhaus, Michaela Kreyenfeld, and Heike Trappe (Felt) Body.Sports, Medicine, and Media 117 Robert Gugutzerand Claudia Peter Gender 133 Paula-Irene Villa and Sabine Hark Globalization and Transnationalization 149 Anja Weiß GlobalSouth 165 EvaGerharz and Gilberto Rescher HistoryofSociology 181 Stephan Moebius VI Contents Life Course 197 Johannes Huinink and Betina Hollstein Media and Communication 211 Andreas Hepp Microsociology 227 RainerSchützeichel Migration 245 Ludger Pries Mixed-Methods and MultimethodResearch 261 FelixKnappertsbusch, Bettina Langfeldt, and Udo Kelle Organization 273 Raimund Hasse Political Sociology 287 Jörn Lamla Qualitative Methods 301 Betina Hollstein and Nils C. -

Vom Erfolg Überholt? Feministische Ambivalenzen Der Gegenwart Hark, Sabine 2014

Repositorium für die Geschlechterforschung Vom Erfolg überholt? Feministische Ambivalenzen der Gegenwart Hark, Sabine 2014 https://doi.org/10.25595/332 Veröffentlichungsversion / published version Sammelbandbeitrag / collection article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Hark, Sabine: Vom Erfolg überholt? Feministische Ambivalenzen der Gegenwart, in: Hänzi, Denis; Matthies, Hildegard; Simon, Dagmar (Hrsg.): Erfolg. Konstellationen und Paradoxien einer gesellschaftlichen Leitorientierung (Baden- Baden: Nomos Verlag, 2014), 76-91. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25595/332. Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer CC BY 4.0 Lizenz (Namensnennung) This document is made available under a CC BY 4.0 License zur Verfügung gestellt. Nähere Auskünfte zu dieser Lizenz finden (Attribution). For more information see: Sie hier: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.en https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.de www.genderopen.de Denis Hänzi 1 Hildegard Matthies Dagmar Simon [Hrsg.] Erfolg Konstellationen und Paradoxien einer gesellschaftlichen Leitorientierung Leviathan Sonderband 29 1 2014 0 Nomos Die Publikation wurde mit Mitteln des Bundesministeriums für Bildung und Forschung sowie des Europäischen Sozialfonds der Europäischen Union unter den Förderkenn• Leviathan zeichen 01FP0848 und 01FP0849 gefördert. Die Verantwortung für den Inhalt dieser Veröffentlichung liegt bei den Autor_innen. Jahrgang 42 ·Sonderband 29 · 2014 Inhaltsübersicht Denis Hänzi, Hildegard Matthies und Dagmar Simon Einleitung ....................... -

Gender Paula-Irene Villaand Sabine Hark

Gender Paula-Irene Villaand Sabine Hark Abstract: Researchinthe field of the sociologyofgenderincludes theoretical, em- pirical, and practical studies and drawsonthe entire rangeofsociological methods and theories. This chapter reconstructs the more recent developments in the German- languagesociologyofgender along the lines of key issues―decentering,inequality and difference,intersectionality,care and precarization, and the body―and situates them in theoretical genealogies.Finally, we highlight current debates to outline av- enues for future research. Keywords: Gender,social theory,sexuality,social differences, care, intersectionality 1Introduction In 2019,forty years after the foundingofthe “Women’sStudies in Sociology” section in the German Sociological Association, gender studies are an integralpart of socio- logical research and teaching. The sociologyofgenderincludes theoretical,empirical, and practical (e.g., policy-oriented) approaches and drawsonthe entire rangeof sociological methodsand theories. Being multidisciplinary by nature, sociological gender studies also bridges disciplinary boundaries. Thesociologyofgenderisa constitutive element of the approximately25academic gender-studies programs (B.A./ M.A.) at German universities, most of which takeamultidisciplinary approach. Re- gardless of institution or location, all these programs basicallylist three aspects as their common denominator:apart from inter-and transdisciplinarity,these include “the ‘social category of gender’ as the label for their subject areaand acritical stance -

Contending Directions. Gender Studies in the Entrepreneurial University

Women's Studies International Forum 54 (2016) 84–90 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Women's Studies International Forum journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/wsif Contending directions. Gender studies in the entrepreneurial university Sabine Hark Technische Universität Berlin ZIFG, MAR 2-4, Marchstraße 23, 10587 Berlin, Germany article info synopsis Available online 14 July 2015 This article explores the ambivalences and aporias that arouse from the institutionalization of degree-granting programs of Gender Studies in German-speaking countries at a time in which universities are being transformed into entrepreneurial managerially governed organizations. It asks if Gender Studies is a proactive element of those transformation processes or has, as a kind of premium segment of the academic market, even profited from them. It asks if Gender Studies has amassed sufficient academic capital to determine the rules of the academic “game” in Bourdieu's sense or if it is falling victim to global processes of academic accumulation and segmentation. The paper's main argument will be that if the paradoxical precondition for dissent is participation, and if critique and regulation are tied up in a fraught but intimate connection, then the point will be to reflect critically upon those circumstances and conditions under which we produce, distribute and consume knowledge. © 2015 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved. In but not of the academy within the civitas academia impose on their scope for action. However, her points are also relevant to the potentials and In her 2009 paper on “clever women” in the university, perspectives of Gender Studies at a time when universities turn the Viennese scholar of Romance languages and literatures into entrepreneurial and/or managerial organizations struc- Friederike Hassauer poses the punning question of how far tured by what, among others, Strathern (2000) has called academia is geschlechtsreif—sexually mature, or ready to be “audit culture”. -

Zertifikatsprogramm Frauenstudien / Gender Studies

Zertifikatsprogramm Frauenstudien / Gender Studies im Wintersemester 2015/16 DirektorInnen des Centrums sind die ProfessorInnen: Helma Lutz, Soziologie GESCHÄFTSFÜHRENDE DIREKTORIN ANNA AMELINA, Soziologie STELLVERTRETENDE GESCHÄFTSFÜHRENDE DIREKTORIN Phil Langer, Soziologie STELLVERTRETENDER GESCHÄFTSFÜHRENDER DIREKTOR Ursula Apitzsch, Soziologie/ Politikwissenschaft Susanne Bauer, Soziologie Birgit Blättel-Mink, Soziologie Barbara Friebertshäuser, Erziehungswissenschaften Ute Gerhard, Soziologie Robert Gugutzer, Sportwissenschaften Kira Kosnick, Soziologie Verena Kuni, Kunstpädagogik Thomas Lemke, Soziologie Susanne Opfermann, Amerikanistik Brita Rang, Erziehungswissenschaften Uta Ruppert, Politikwissenschaft Ute Sacksofsky, Rechtswissenschaft Susanne Schröter, Ethnologie Ulla Wischermann, Soziologie Sekretariat: Barbara Kowollik Wissenschaftliche Koordinatorin: Marianne Schmidbaur Wissenschaftliche und Studentische Hilfskräfte: Anna Krämer Lucyna Kühnemann Kristof Schütt Goethe-Universität Postfach PEG 4 Theodor-W.-Adorno-Platz 6 Tel.: +49 (0) 69-798-35100 PEG 2.G 154 email: [email protected] D-60629 Frankfurt a. M. homepage: http://www.cgc.uni-frankfurt.de Inhalt Das Cornelia Goethe Centrum stellt sich vor 2 Was ist das Cornelia Goethe Centrum? 2 Wer arbeitet im Centrum? 2 1 Was bietet das Centrum Studierenden? 3 1.1 Zertifikatsprogramm Frauenstudien/Gender Studies 3 1.2 Terminankündigungen Wintersemester 2015/16 5 2 Lehrveranstaltungen 7 Fachbereich 01: Rechtswissenschaft 7 Fachbereich 03: Gesellschaftswissenschaften -

Room 105 10:30-11:15

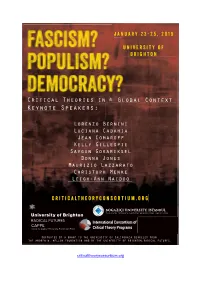

University of Brighton, Edward Street Building 154-155 Edward Street, Brighton, BN2 0JG Wednesday 23 January Registration 9:00-10:30 Edward Street Building Reception Edward Street Lecture Theatre Room 105 10:30-11:15 Conference Opening: Fascism and Populism in Context: From Erdogan to Brexit Volkan Çıdam, Boğaziçi University, Turkey Mark Devenney, University of Brighton, UK Zeynep Gambetti, Boğaziçi University, Turkey Clare Woodford, University of Brighton, UK 11:15-13:15 Keynote Lectures Chair: Zeynep Gambetti Maurizio Lazzarato, Matisse/CNRS, Pantheon-Sorbonne University (University Paris I), France: De Pinochet à Bolsonaro et retour : La vague néo - fasciste qui balaye la planète Jean Comaroff, Harvard University, USA: Crime, sovereignty, and the state: The popular metaphysics of disorder Lunch | 13:15-14:15 | Rooms 210/211 1 Session 1: 14:15-15:45 Panel 1: Decolonising Critical Theory Room: 304 Chair: German Primera Hilla Dayan, Amsterdam University College, Netherlands: Decolonising the population domain: Reflections on apartheid and Israel in the 1950s Liam Farrell and Hasse C, National University of Ireland, Ireland: Critical theory outside “Civilization”: “Women,” slavery, equality and democratic politics in the political theory of Abdullah Öcalan Paolo Bolaños, University of Santo Tomas, Philippines : Critical theory for/from the margins: Appropriating critical theory in the Philippines and what can critical theory learn from the margins Panel 2: The Fascism(s) of Everyday Life Room: 103 Chair: Zeynep Gambetti Anthony Faramelli, -

Criticaltheoryconsortium.Org

criticaltheoryconsortium.org University of Brighton, Edward Street Building 154-155 Edward Street, Brighton, BN2 0JG Wednesday 23 January Registration 9:00-10:30 Edward Street Lecture Theatre Room 105 Tea and coffee available in Rooms 210/211 Edward Street Lecture Theatre Room 105 10:30-11:00 Conference Opening Conference Convenors: Volkan Çıdam, Boğaziçi University, Turkey Mark Devenney, University of Brighton, UK Zeynep Gambetti, Boğaziçi University, Turkey Clare Woodford, University of Brighton, UK 11:00-13:00 Keynote Lectures Maurizio Lazzarato, Matisse/CNRS, Pantheon-Sorbonne University (University Paris I), France: De Pinochet à Bolsonaro et retour : La vague néo - fasciste qui balaye la planète Jean Comaroff, Harvard University, USA: Crime, sovereignty, and the state: The popular metaphysics of disorder Lunch | 13:00-14:15 | Rooms 210/211 2 Session 1: 14:15-15:45 Panel 1: Decolonising Critical Theory 1 Room: 105 Chair: to be announced Jishnu Guha-Majumdar, Johns Hopkins University, USA: Carceral humanism and the animalized politics of prison abolition Liam Farrell and Hasse C, National University of Ireland, Ireland: Critical theory outside “Civilization”: “Women”, slavery, equality and democratic politics in the political theory of Abdullah Öcalan Paolo Bolaños, University of Santo Tomas, Philippines : Critical theory for/from the margins: Appropriating critical theory in the Philippines and what can critical theory learn from the margins Panel 2: Authoritarian