Using NPR's Planet Money Podcast in Principles of Macroeconomics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Looking for Podcast Suggestions? We’Ve Got You Covered

Looking for podcast suggestions? We’ve got you covered. We asked Loomis faculty members to share their podcast playlists with us, and they offered a variety of suggestions as wide-ranging as their areas of personal interest and professional expertise. Here’s a collection of 85 of these free, downloadable audio shows for you to try, listed alphabetically with their “recommenders” listed below each entry: 30 for 30 You may be familiar with ESPN’s 30 for 30 series of award-winning sports documentaries on television. The podcasts of the same name are audio documentaries on similarly compelling subjects. Recent podcasts have looked at the man behind the Bikram Yoga fitness craze, racial activism by professional athletes, the origins of the hugely profitable Ultimate Fighting Championship, and the lasting legacy of the John Madden Football video game. Recommended by Elliott: “I love how it involves the culture of sports. You get an inner look on a sports story or event that you never really knew about. Brings real life and sports together in a fantastic way.” 99% Invisible From the podcast website: “Ever wonder how inflatable men came to be regular fixtures at used car lots? Curious about the origin of the fortune cookie? Want to know why Sigmund Freud opted for a couch over an armchair? 99% Invisible is about all the thought that goes into the things we don’t think about — the unnoticed architecture and design that shape our world.” Recommended by Scott ABCA Calls from the Clubhouse Interviews with coaches in the American Baseball Coaches Association Recommended by Donnie, who is head coach of varsity baseball and says the podcast covers “all aspects of baseball, culture, techniques, practices, strategy, etc. -

Podcasting As Public Media: the Future of U.S

International Journal of Communication 14(2020), 1683–1704 1932–8036/20200005 Podcasting as Public Media: The Future of U.S. News, Public Affairs, and Educational Podcasts PATRICIA AUFDERHEIDE American University, USA DAVID LIEBERMAN The New School, USA ATIKA ALKHALLOUF American University, USA JIJI MAJIRI UGBOMA The New School, USA This article identifies a U.S.-based podcasting ecology as public media and then examines the threats to its future. It first identifies characteristics of a set of podcasts in the United States that allow them to be usefully described as public podcasting. Second, it looks at current business trends in podcasting as platformization proceeds. Third, it identifies threats to public podcasting’s current business practices. Finally, it analyzes responses within public podcasting to the potential threats. The article concludes that currently, the public podcast ecology in the United States maintains some immunity from the most immediate threats, but there are also underappreciated threats to it, both internally and externally. Keywords: podcasting, public media, platformization, business trends, public podcasting ecology As U.S. podcasting becomes a commercially viable part of the media landscape, are its public service functions at risk? This article explores that question, in the process postulating that the concept of public podcasting has utility in describing not only a range of podcasting practices, but also an ecology within the larger podcasting ecology—one that permits analysis of both business methods and social practices, and one that deserves attention and even protection. This analysis contributes to the burgeoning literature on Patricia Aufderheide: [email protected] David Lieberman: [email protected] Atika Alkhallouf: [email protected] Jiji Majiri Ugboma: [email protected] Date submitted: 2019‒09‒27 Copyright © 2020 (Patricia Aufderheide, David Lieberman, Atika Alkhallouf, and Jiji Majiri Ugboma). -

KCUR 18073107 Fall Newsletter 2018.Indd

FALL 2018 THE MEMBER NEWSLETTER OF KCUR 89.3 COUNTDOWN TO THE MIDTERMS MEET THE TEAM DEDICATED TO KEEPING YOUR TRUST THIS ELECTION SEASON ON THE How we’re working COVER Meet the team to earn the trust delivering election coverage you can you’ve placed in us trust as we enter the midterms (left to right): Madeline Fox, t KCUR we are committed Amy Jeff ries, Lisa to fact-based journalism and Agreat storytelling. To better Rodriguez, Brian serve members like you, we’ve Ellison, Samuel King, been working hard to expand Sam Zeff and Maria our audience on regional issues Carter. Photo by and connect with listeners on Brandon Parigo. both sides of the aisle and both sides of the state line. We are See story ............ 6-7 always looking for partners that allow us to incorporate a broad perspective and delve deeper into the most signifi cant issues of WHAT’S our time. This summer, we added Samuel INSIDE King, a reporter dedicated solely We’re incredibly proud of our growth and partnerships, but StoryCorps makes to Missouri politics, to our team. most of all, we’re proud of the another trip to He’ll be working closely with partner stations in St. Louis relationship we have with you. Kansas City to hear and Columbia as we cover the As trust in media continues to tales of life, love and mid-term elections together. In erode across the country, we being a baby ...... 2-3 addition, we are continuing to are constantly hearing how grow the Kansas News Service’s much you value our fact-based Achieving justice ability to cover the state with journalism. -

English 1 Distance Learning for April 6, 2020 Through May 1, 2020

ENGLISH 1 DISTANCE LEARNING FOR APRIL 6, 2020 THROUGH MAY 1, 2020 General Instructions: Hold down the Ctrl key and click on hyperlinks to go to the sites. 1. Each week, choose ONE activity to do from the menu below. A. You must choose one activity from each COLUMN by the end of the three weeks. In other words, complete one Reading activity, one Writing activity, and one Social Connection activity by 5/4/20. B. Each activity should take between 45 and 90 minutes. 2. For each activity, create a new document, put it in MLA format, and use the title of the activity you are completing. You may use your school One Drive, Microsoft Word, or Google Docs to create the document, but the English 1 teachers highly recommend using your school One Drive. 3. Submit ALL THREE documents with the three separate activities to your teacher via turnitin.com. Each assignment in turnitin.com will say Choice Activity 1, Choice Activity 2, and Choice Activity 3. 4. Last, by 5/3/20, send thank you notes via email to THREE teachers or staff members from any school you have attended. Instructions are at the bottom of this document. Reading Writing Social Connection Independent Reading: Khan Academy Grammar Practice: Media Review: 1) Click here to watch a video introduction to grammar. Create a Flip Grid review of film, TV show (or episode), Directions: 2) Create a Khan Academy account and join the music (album, artist, new song), video game, or book you 1) Read your Independent Reading book for 15 9th grade class: completed over the course of the school closure. -

May 6, 2019 Dear Parents/Guardians/Students: The

May 6, 2019 Dear Parents/Guardians/Students: The focus of AP Language and Composition is nonfiction reading and becoming a world scholar, so in preparation for this type of reading we are asking you to listen to one podcast from list below and to continue to listen to new episodes from this podcast over the summer. • 99% Invisible: 99% Invisible is about all the thought that goes into the things we don’t think about — the unnoticed architecture and design that shape our world. • This American Life: Primarily a journalistic non-fiction program, it has also featured essays, memoirs, field recordings, short fiction, and found footage. • The Moth: Since its launch in 1997, The Moth has presented thousands of true stories, told live and without notes, to standing-room-only crowds worldwide. Moth storytellers stand alone, under a spotlight, with only a microphone and a roomful of strangers. The storyteller and the audience embark on a high-wire act of shared experience which is both terrifying and exhilarating. • Radiolab: Radiolab is a show about curiosity. Where sound illuminates ideas, and the boundaries blur between science, philosophy, and human experience. • StarTalk Radio: Radio program devoted to all things space and is hosted by renowned astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson • Hidden Brain: Shankar Vedantam uses science and storytelling to reveal the unconscious patterns that drive human behavior, shape our choices and direct our relationships. • Revisionist History: Revisionist History is Malcolm Gladwell’s journey through the overlooked and the misunderstood. Every episode re-examines something from the past—an event, a person, an idea, even a song—and asks whether we got it right the first time. -

Weekly Schedule (.Pdf)

Monday - Friday Saturday Sunday 93.9 FM AM 820 93.9 FM AM 820 93.9 FM AM 820 5:00 AM 5:00 AM BBC World Service 5:00 AM BBC World Service BBC World Service BBC World Service 5:30 5:30 The Capitol Connection 5:30 6:00 6:00 6:00 Innovation Hub Left, Right & Center The Splendid Table The Capitol Pressroom 6:30 Morning Edition Morning Edition 6:30 6:30 7:00Marketplace Morning Rpt. 6:50 & 8:50 Marketplace Morning Rpt. 6:50 & 8:50 7:00 7:00 On the Media The Splendid Table On Being The Takeaway Politics 7:30 7:30 7:30 8:00 8:00 8:00 8:30 8:30 Weekend Edition Weekend Edition 8:30 9:00 9:00 Saturday Weekend Edition Sunday Weekend Edition 9:00 BBC Newshour The Takeaway 9:30 9:30Saturday Sunday 9:30 10:00 10:00The New Yorker 10:00 On the Media 10:30 10:30Radio Hour 10:30 The Brian Lehrer Show The Brian Lehrer Show 11:00 11:00Wait, Wait Wait, Wait The New Yorker 11:00 Reveal 11:30 11:30Don't Tell Me Don't Tell Me Radio Hour 11:30 NOON NOONSeptember Special NOON Radiolab The Takeaway Politics This American Life 12:30 PM 12:30 PMProgramming 12:30 PM All Of It with Alison Stewart All Of It with Alison Stewart 1:00 1:00 Planet Money 1:00 Snap Judgment This American Life The Moth 1:30 1:30 How I Built This 1:30 2:00Fresh Air (Monday-Thursday) 2:00 2:00 1A The Moth Freakonomics Radio TED Radio Hour On Being 2:30Science Friday (Friday) 2:30 2:30 3:00 3:00September Special Wait, Wait 3:00 The Takeaway BBC Newshour Fresh Air Weekend On the Media 3:30 3:30Programming Don't Tell Me 3:30 4:00 4:00 4:00 BBC Newshour BBC Newshour BBC Newshour BBC Newshour 4:30 -

New Politics Podcast, All Things Considered Host & More

ON AIR & ONLINE SEPTEMBER 2016 Planet Money Oil Series Welcome Brady Carlson Chris Thile on APHC WI Vote on the Road Job Openings at WPR Featured Photo Every day our music hosts find the best new releases, historic WPR Launches New Politics Podcast performances and hidden gems for our classical, world and folk programs. Thanks to some upgrades to our library If you can't get enough of Wisconsin politics, or you have a hard time software, you can now keeping up with the news, WPR's new Politics Podcast might be the get the track, album and answer. The short, 10 to 15 minute weekly episodes are designed to artist names for most of fill you in on stories you might have missed and dive a bit deeper on our classical and folk the stories everyone is talking about. music selections at wpr.org. Hosted by John Wilson (pictured center), a digital journalist at wpr.org and self-described "politics nerd," each podcast features conversations with WPR reporters like Capital Bureau Chief Shawn Johnson (right) and Capital Reporter Laurel White (left), among Sound Bites others. The tone is light, but the topics are robust - like the recently leaked papers from the "John Doe 2" investigation or the influence of the Marquette Law School Poll on state politics. Presidential Debates Start September 26 Election season is in full swing and WPR is "Political reporters are in the business because they're genuinely bringing the candidate interested in this stuff - they live and breathe and geek out about it," debates to you. -

CPB Station Activity Survey for 2017 1. Describe Your Overall

Section 6: Local Content & Services Report– CPB Station Activity Survey for 2017 1. Describe your overall goals and approach to address identified community issues, needs, and interests through your station’s vital local services, such as multiplatform long and short-form content, digital and in-person engagement, education services, community information, partnership support, and other activities, and audiences you reached or new audiences you engaged. New York Public Radio (NYPR) is an independent nonprofit news and cultural organization that owns and operates a portfolio of radio stations, digital properties, and a performance space in Manhattan. NYPR’s commitment to the community and to public service is central to its mission. NYPR produces groundbreaking news and cultural programming that invite ongoing civic dialogue. We continuously explore ways to be an essential resource for New York City’s diverse communities, promoting inclusion, awareness and intercultural engagement. NYPR is dedicated to developing meaningful partnerships, promotions and special events to extend our mission. By immersing ourselves in the community, NYPR addresses issues that reflect the issues and interests of our time and help tell the stories that matter. We constantly work to increase our relevance as a public radio station and ensure that our programming reflects the voices of the New York metropolitan area. Through content across the station’s distribution channels and platforms on-air, online and on the ground, NYPR strengthens community connections throughout the city. We are committed to reflecting the values, concerns and goals of our multi-cultural and multi-ethnic listeners. NYPR provides responsive services and tools that enable our audience to access our content anywhere any time. -

Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday

Time: Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday Sunday 12am Ask Me Another On Point On Point On Point On Point On Point PIANO JAZZ 1am Wait Wait On Point On Point On Point On Point On Point JAZZ NITE 2am Bullseye 1A 1A 1A 1A 1A Thistle & Shamrock 3am Fresh Air Weekend 1A 1A 1A 1A 1A All Songs-ALT Latino CONVERSATIONS 4am Ted Radio Hour Fresh Air Fresh Air Fresh Air Fresh Air Fresh Air WORLD CAFÉ 5am Morning Edition Morning Edition Morning Edition Morning Edition Morning Edition Bullseye Fresh Air Weekend 6am Morning Edition Morning Edition Morning Edition Morning Edition Morning Edition Latino USA Latino USA 7am Morning Edition Morning Edition Morning Edition Morning Edition Morning Edition Only A Game Ted Radio hour 8am Morning Edition Morning Edition Morning Edition Morning Edition Morning Edition Weekend Edition Weekend Edition 9am Morning Edition Morning Edition Morning Edition Morning Edition Morning Edition Weekend Edition Weekend Edition 10am ON POINT ON POINT ON POINT ON POINT ON POINT *It’s been a Min. Weekend Edition 11am ON POINT ON POINT ON POINT ON POINT ON POINT *Hidden Brain Weekend Edition *Planet Money/ 12pm FRESH AIR FRESH AIR FRESH AIR FRESH AIR FRESH AIR Best of car talk How I Built 1pm HERE AND NOW HERE AND NOW HERE AND NOW HERE AND NOW HERE AND NOW Wait Wait Wait Wait 2pm HERE AND NOW HERE AND NOW HERE AND NOW HERE AND NOW HERE AND NOW Ask Me Another Ask Me Another Fresh Air Bullseye 3pm 1A 1A 1A 1A 1A Weekend 4pm 1A 1A 1A 1A 1A TED Radio Latino USA 5pm ALL THINGS ALL THINGS ALL THINGS ALL THINGS ALL THINGS All Things All Things Considered 6pm ALL THINGS ALL THINGS ALL THINGS ALL THINGS ALL THINGS All Things All Things Considered *PLANET / Thistle & 7pm ASK ME ANOTHER *Hidden Brain ONLY A GAME TED From The Top HOW I BUILT Shamrock 8pm BULLS EYE TED LATINO USA Wait Wait Piano Jazz Mountain Stage *It’s been a Min. -

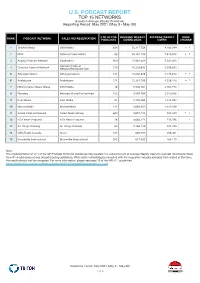

U.S. PODCAST REPORT TOP 15 NETWORKS Based on Average Weekly Downloads Reporting Period: May 2021 (May 3 - May 30)

U.S. PODCAST REPORT TOP 15 NETWORKS Based on Average Weekly Downloads Reporting Period: May 2021 (May 3 - May 30) # OF ACTIVE AVERAGE WEEKLY AVERAGE WEEKLY RANK RANK PODCAST NETWORK SALES REPRESENTATION PODCASTS DOWNLOADS USERS CHANGE 1 Stitcher Media SXM Media 459 35,317,758 9,163,399 1 2 NPR National Public Media 55 35,162,199 7,425,526 1 3 Audacy Podcast Network Cadence13 500 17,982,442 5,542,005 Cumulus Podcast 4 Cumulus Podcast Network Network/Westwood One 270 15,225,592 3,556,832 5 AdLarge/cabana AdLarge/cabana 134 13,050,876 4,173,613 1 6 Audioboom Audioboom 274 12,281,759 4,326,418 1 7 NBCUniversal News Group SXM Media 46 9,926,761 2,764,770 8 Wondery Wondery Brand Partnerships 102 9,589,764 2,910,636 9 Kast Media Kast Media 93 3,795,469 1,514,087 10 WarnerMedia WarnerMedia 114 3,698,251 1,437,168 11 Salem Podcast Network Salem Media Group 662 2,691,743 534,539 1 12 FOX News Podcasts FOX News Podcasts 48 2,665,171 735,796 1 13 All Things Comedy All Things Comedy 52 2,166,142 944,325 14 CBC/Radio-Canada Acast 333 685,707 236,461 15 Bonneville International Bonneville International 252 647,352 184,170 Note: The implementation of v2.1 of the IAB Podcast Technical Guidelines has resulted in a reduced count of Average Weekly Users for podcast downloads made from IP v6 addresses across all participating publishers. While both methodologies complied with the respective industry standard that existed at that time, the results should not be compared. -

WGLT Program Guide, September-October, 2011

Illinois State University ISU ReD: Research and eData WGLT Program Guides Arts and Sciences Fall 9-1-2011 WGLT Program Guide, September-October, 2011 Illinois State University Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/wgltpg Recommended Citation Illinois State University, "WGLT Program Guide, September-October, 2011" (2011). WGLT Program Guides. 238. https://ir.library.illinoisstate.edu/wgltpg/238 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts and Sciences at ISU ReD: Research and eData. It has been accepted for inclusion in WGLT Program Guides by an authorized administrator of ISU ReD: Research and eData. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ALSO IN THIS ISSUE: • Travel to Costa Rica with GLT • Blues Blast Music Awards at Buddy Guy's • Meet Center Stage host Chrissie Strong NPR's Planet Money Team "Faces" Bloomington by GLT News Director Willis Kem Is there anything harder to understand than economics and its impact? Not according to NPR's award winning Planet Money team, who have made the recession understandable, if not palatable, over the last few years of their outstanding collective reporting. David Kestenbaum and Jacob Goldstein, two members of the Planet Money team, will be featured at our annual Radio Faces event in Bloomington. I spent a few minutes on the phone with David. stories when we pooled our money and bought one of the toxic assets-those mortgage-backed securities nobody wanted to own. It cost $1,000--five of us put Willis Kem: How did the concept for Planet Money come about? in $200 each. -

Theresa Burroughs, Voting Rights Activist, Dies at 89 in Alabama

Play Live Radio NEDONAWSCATSET LIVE RADIO SHOWS NATIONAL Theresa Burroughs, Voting Rights Activist, Dies At 89 In Alabama LISTEN · 3:10 PLAYLIST Download Transcript May 24, 2019 · 11:31 PM ET Heard on All Things Considered DEBBIE ELLIOTT BARBARA CAMPBELL Civil rights "foot soldier" Theresa Burroughs in 2016, in front of a photo of the day she was arrested in 1965. Burroughs has died at age 89. Debbie Elliott/NPR Theresa Burroughs, who proudly called herself a foot soldier for the right to vote, has died in Greensboro, Ala. She was 89. Greensboro is part of Alabama's Black Belt, a region named for its rich black soil, and known for its oppression of black citizens during the Jim Crow era, including erecting obstacles to the vote. She said no one around her talked about it then out of fear. "When I was a child," she recalled in a 2016 interview with NPR, "I would see white people getting dressed and going on Tuesdays. And I would wonder where are they going? They said they were going to vote. ... And I said, 'Why can't we vote?' " But as an adult she went to the county courthouse 10 times before the registrar finally recognized her right to vote. She says sometimes she was tested with irrelevant questions, one of which as she told Story Corps, was how many black jelly beans there were in a jar. Then, as she began to tire of trying, on one occasion she was told she must recite the preamble to the Constitution. "I didn't say the preamble.