Effect of Joint Forest Management Program on Community Forest Management in Odisha

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of Trade and Commerce in the Princely States of Nayagarh District (1858-1947)

Odisha Review April - 2015 An Analysis of Trade and Commerce in the Princely States of Nayagarh District (1858-1947) Dr. Saroj Kumar Panda The present Nayagarh District consists of Ex- had taken rapid strides. Formerly the outsiders princely states of Daspalla, Khandapara, only carried on trade here. But of late, some of Nayagarh and Ranpur. The chief occupation of the residents had turned traders. During the rains the people of these states was agriculture. When and winter, the export and import trade was the earnings of a person was inadequate to carried on by country boats through the river support his family, he turned to trade to Mahanadi which commercially connected the supplement his income. Trade and commerce state with the British districts, especially with attracted only a few thousand persons of the Cuttack and Puri. But in summer the trade was Garjat states of Nayagarh, Khandapara, Daspalla carried out by bullock carts through Cuttack- and Ranpur. On the other hand, trade and Sonepur Road and Jatni-Nayagarh-Daspalla commerce owing to miserable condition of Road. communications and transportations were of no importance for a long time. Development of Rice, Kolthi, Bell–metal utensils, timbers, means of communication after 1880 stimulated Kamalagundi silk cloths, dying materials produced the trade and commerce of the states. from the Kamalagundi tree, bamboo, mustard, til, molasses, myrobalan, nusevomica, hide, horns, The internal trade was carried on by means bones and a lot of minor forest produce, cotton, of pack bullocks, carts and country boats. The Mahua flower were the chief articles of which the external trade was carried on with Cuttack, Puri Daspalla State exported. -

Nayagarh District

Govt. of India MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD OF NAYAGARH DISTRICT South Eastern Region Bhubaneswar May , 2013 1 District at a glance SL. ITEMS STATISTICS NO 1. GENERAL INFORMATION a) Geographical area (Sq.Km) 3,890 b) Administrative Division Number of Tehsil/Block 4 Tehsils/8 Blocks Number of GramPanchayats(G.P)/villages 179 G.Ps, 1695 villages c) Population (As on 2011 census) 9,62,215 2. GEOMORPHOLOGY Major physiographic units Structural Hills, Denudational Hills, Residual Hills, Lateritic uplands, Alluvial plains, Intermontane Valleys Major Drainages The Mahanadi, Burtanga, Kaunria, Kamai & the Budha nadi 3. LAND USE (Sq. Km) a) Forest area: 2,080 b) Net area sown: 1,310 4. MAJOR SOIL TYPES Alfisols, Ultisols 5. IRRIGATION BY DIFFERENT SOURCES (Areas and number of structures) Dug wells 14707 dug wells with Tenda, 783 with pumps Tube wells/ Bore wells 16 shallow tube wells, 123 filter point tube well Gross irrigated area 505.7 Sq.Km 6. NUMBERS OF GROUND WATER 16 MONITORING WELLS OF CGWB (As on 31.3.2007) Number of Dug Wells 16 Number of Piezometers 5 7. PREDOMINANT GEOLOGICAL Precambrian: Granite Gneiss, FORMATIONS Khondalite, Charnockite Recent: Alluvium 9. HYDROGEOLOGY Major water bearing formation Consolidated &Unconsolidated formations Premonsoon depth to water level Min- 0.65 (Daspalla- I) during 2006(mbgl) Max- 9.48 (Khandapada)& Avg. 4.92l 2 Min –0.17 (Nayagarh), Post-monsoon Depth to water level Max- 6.27 (Daspalla-II) & during 2006(mbgl) Avg.- 2.72 8 number of NHS shows Long term water level trend in 10 yrs rising trend from 0.027m/yr to (1997-2007) in m/yr 0.199m/yr & 8 show falling trend from 0.006 to 0.106m/yr. -

Annual Report 2018 - 19

40th YEAR OF GRAM VIKAS ANNUAL REPORT 2018 - 19 02 Gram Vikas Annual Report 2018 - 19 On the cover: Gram Vikas’ Ajaya Behera captures Hitadei Majhi as she walks up the hill to till the land for plantations that will protect and nourish water sources for sustainability. In Nuapada village, Kalahandi district, Odisha. Gram Vikas is a rural development organisation working with the poor and marginalised communities of Odisha, since 1979, to make sustainable improvements in their quality of life. We build their capabilities, strengthen community institutions and mobilise resources to enable them to lead a dignifed life. More than 600,000 people in 1700 villages have advanced their lives through this partnership. www.gramvikas.org CONTENTS Chairman’s Message ........................ 01 Our Work: Activities and Achievements 2018 - 19 ................. 05 The Status Assessment Survey ......................................................... 31 Disaster Relief and Rehabilitation ........................................ 32 Water ....................................... 06 Livelihoods .............................13 Fortieth Anniversary Celebrations ........................................... 35 Governance and Management ... 40 Human Resources .............................. 43 Communications ................................. 51 Accounting and Finance ................. 53 Sanitation and Hygiene ...........19 Habitat and Technologies ..... 23 Education ............................... 27 Village Institution ................... 29 CHAIRMAN’S MESSAGE -

Brief Industrial Profile of NAYAGARH District 2019-20

Government of India Ministry of MSME Brief Industrial Profile of NAYAGARH District 2019-20 Carried out by MSME - Development Institute, Cuttack (Ministry of MSME, Govt. of India,) (As per guidelines of O/O DC (MSME), New Delhi) Phone: 0671-2548049, 2548077 Fax: 0671-2548006 E. Mail:[email protected] Website: www.msmedicuttack.gov.in ii F O R E W O R D Every year Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises Development Institute, Cuttack under the Ministry of Micro, Small & Medium Enterprises, Government of India has been undertaking the Industrial Potentiality Survey for the districts in the state of Odisha and brings out the Survey Report as per the guidelines issued by the office of Development Commissioner (MSME), Ministry of MSME, Government of India, New Delhi. Under its Annual Action Plan 2019-20, all the districts of Odisha have been taken up for the survey. This Industrial Potentiality Survey Report of Nayagarh district covers various parameters like socio- economic indicators, present industrial structure of the district, and availability of industrial clusters, problems and prospects in the district for industrial development with special emphasis on scope for setting up of potential MSMEs. The report provides useful information and a detailed idea of the industrial potentialities of the district. I hope this Industrial Potentiality Survey Report would be an effective tool to the existing and prospective entrepreneurs, financial institutions and promotional agencies while planning for development of MSME sector in the district. I like to place on record my appreciation for Dr. Shibananda Nayak, AD(EI) of this Institute for his concerted efforts to prepare this report under the guidance of Dr. -

Odisha Information Commission Block B-1, Toshali Bhawan, Satyanagar

Odisha Information Commission Block B-1, Toshali Bhawan, Satyanagar, Bhubaneswar-751007 * * * Weekly Cause List from 27/09/2021 to 01/10/2021 Cause list dated 27/09/2021 (Monday) Shri Balakrishna Mohapatra, SIC Court-I (11 A.M.) Sl. Case No. Name of the Name of the Opposite party/ Remarks No Complainant/Appellant Respondent 1 S.A. 846/18 Satyakam Jena Central Electricity Supply Utility of Odisha, Bhubaneswar City Distribution Division-1, Power House Chhak, Bhubaneswar 2 S.A.-3187/17 Ramesh Chandra Sahoo Office of the C.D.M.O., Khurda, Khurda district 3 S.A.-2865/17 Tunuram Agrawal Office of the General Manager, Upper Indravati Hydro Electrical Project, Kalahandi district 4 S.A.-2699/15 Keshab Behera Office of the Panchayat Samiti, Khariar, Nawapara district 5 S.A.-2808/15 Keshab Behera Office of the Block Development Officer, Khariar Block, Nawapara 6 S.A.-2045/17 Ramesh Chandra Sahoo Office of the Chief District Medical Officer, Khurda, Khurda district 7 C.C.-322/17 Dibakar Pradhan Office of the Chief District Medical Officer, Balasore district 8 C.C.-102/18 Nabin Behera Office of the C.S.O., Boudh, Boudh district 9 S.A.-804/16 Surasen Sahoo Office of the Chief District Medical Officer, Nayagarh district 10 S.A.-2518/16 Sirish Chandra Naik Office of the Block Development Officer, Jashipur Block, Mayurbhanj 11 S.A.-1249/17 Deepak Kumar Mishra Office of the Drugs Inspector, Ganjam-1, Range, Berhampur, Ganjam district 12 S.A.-637/18 M. Kota Durga Rao Odisha Hydro Power Corporation Ltd., Odisha State Police Housing & Welfare Coroporation Building, Vani Vihar Chowk, Bhubaneswar 13 S.A.-1348/18 Manini Behera Office of the Executive Engineer, GED-1, Bhubaneswar 14 S.A. -

Government of Odisha St & Sc Development Department

GOVERNMENT OF ODISHA ST & SC DEVELOPMENT DEPARTMENT OFFICE ORDER No i°5761 /SSD. Bhubaneswar Dated 09.06.2016 The following Welfare Extension Officers working in ST&SC Development Department are hereby transferred and posted to the Blocks/ Offices as mentioned against their names. SI Name y Present Posting Transferred to 1 Sri.Kalapatru Panda WEO Angul, Angul WED TangiChowdwar, District Cuttack District 2 Ms. Sreelekha Nayak WED Jajpur, Jajpur WED Banpur, Khurda District District 3 Ms. Deepa Sethi WEO Banpur, Khurda OSFDC, Bhubaneswar District 4 Sri. Bijay Kumar SCSTRTI, WEO Phiringia, Chinara Bhubaneswar Kandhamal District 5 Ms. Sushree Patra WEO Phiringia, SCSTRTI, Bhubaneswar Kandhmal District 6 Ms. Smitashree Jena WED Baliguda, WED Kankadahad, Kandhmal District Dhenkanal District 7 Sri. Kailash Chandra WEO Hinjlikatu, WEO Ghatgaon, Keonjhar Satpathy Gangam District District 8 Santosh Kumar Panda WED Dharakote, WEO Raghunathpur, Ganjam District Jagatsinghpur District, 9 Sri. Basanta Tarai WEO Loisinga, WED Kabisurjyanagar, Bolangir District Ganjam District 10 Sri.Jugal Kishore WEO Kabisurjyanagar, WED Loisingha Bolangir Behera Ganjam District 11 Sri.Malay Ranjan WED Gudvela, WED Nuagaon, Nayagarh Chinara Balangir District District 12 Sri.Sukanta Madhab WED Aska, Ganjam WED Bari Block, Jajpur Rout District District 13 Sri.Dilip Kumar Patnaik WED Pottangi, WEO Aska, Ganjam Koraput District District 14 Sri.Sanjay Kumar WED Tiring, WED Kujang, Nayak Mayurbhanj District Jagatsinghpur District 15 Sri.Pradipta Kumar WEO CBDA Sunabeda, WED -

Boudh District, Odisha River Sand

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT (DSR) OF BOUDH DISTRICT, ODISHA FOR RIVER SAND ODISHA BOUDH DIST. As per Notification No. S.O. 3611(E) New Delhi, 25th July, 2018 MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, FOREST AND CLIMATE CHANGE (MoEF & CC) Prepared by COLLECTORATE, BOUDH CONTENT SL.NO DESCRIPTION PAGE NO 1 INTRODUCTION 1 2 OVERVIEW OF MINING ACTIVITIES IN THE DISTRICT 3 3 LIST OF LEASES WITH LOCATION, AREA AND PERIOD OF 3 VALIDITY 4 DETAILS OF ROYALITY COLLECTED 3 5 DETAILS OF PRODUCTION OF SAND 3 6 PROCESS OF DEPOSIT OF SEDIMENTS IN THE RIVERS 3 7 GENERAL PROFILE 4 8 LAND UTILISATION PATTERN 13 9 PHYSIOGRAPHY 13 10 RAINFALL 14 11 GEOLOGY AND MINERAL WALTH 14 12 DRAINAGE AND IRRIGATION PATTERN 16 13 DETAILS OF ECO-SENSTIVE ZONE AREA 19 14 MINING LEASES MARKED ON THE MAP OF THE DISTRICT 20 15 LIST OF LOI HOLDERS ALONG WITH VALIDITY 20 16 QUALITY/ GRADE OF MINERAL 20 17 USE OF MINERAL 20 18 DEMAND & SUPPLY OF THE MINERAL 20 19 DETAILS OF AREA WHERE THERE IS A CLUSTER OF MINING 20 LEASES 20 IMPACT ON THE ENVIRONMENT (AIR, WATER, NOISE, SOIL 21 FLORA & FAUNAL, LAND USE, AGRICULTURE, FOREST ETC.) DUE TO MINING 21 REMEDIAL MEASURES TO MITIGATE THE IMPACT OF 22 MINING ON THE ENVIRONMENT:- 22 ANY OTHER INFORMATION 24 LIST OF PLATES DESCRIPTION PLATE NO INDEX MAP OF THE DISTRICT 1 MAP SHOWING TAHASILS 2 ROAD MAP OF THE DISTRICT 3 MINERAL MAP OF THE DISTRICT 4 LEASE/POTENTIAL AREA MAP OF THE DISTRICT 5 DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT (DSR) BOUDH, DISTRICT PREFACE In compliance to the notification issued by the ministry of environment and forest and Climate Change Notification no. -

Nayagarh.Pdf

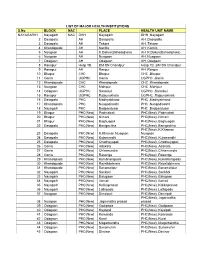

LIST OF MAJOR HEALTH INSTITUTIONS S.No BLOCK NAC PLACE HEALTH UNIT NAME NAYAGARH1 Nayagarh NAC DHH Nayagarh DHH ,Nayagarh 2 Dasapala AH Dasapalla AH ,Dasapalla 3 Dasapala AH Takara AH ,Takara 4 Khandapada AH Kantilo AH ,Kantilo 5 Nuagaon AH K.Dakua(Bahadajhola) AH ,K.Dakua(Bahadajhola) 6 Nuagaon AH Nuagaon AH ,Nuagaon 7 Odagaon AH Odagaon AH ,Odagaon 8 Ranapur Hosp TB BM SN Chandpur Hosp TB ,BM SN Chandpur 9 Ranapur AH Ranpur AH ,Ranpur 10 Bhapur CHC Bhapur CHC ,Bhapur 11 Gania UGPHC Gania UGPHC ,Gania 12 Khandapada CHC Khandapada CHC ,Khandapada 13 Nuagaon CHC Mahipur CHC ,Mahipur 14 Odagaon UGPHC Sarankul UGPHC ,Sarankul 15 Ranapur UGPHC Rajsunakhala UGPHC ,Rajsunakhala 16 Dasapala PHC Madhyakhand PHC ,Madhyakhand 17 Khandapada PHC Nuagadiasahi PHC ,Nuagadiasahi 18 Nayagarh PHC Badpandusar PHC ,Badpandusar 19 Bhapur PHC(New) Padmabati PHC(New) ,Padmabati 20 Bhapur PHC(New) Nimani PHC(New) ,Nimani 21 Bhapur PHC(New) Baghuapali PHC(New) ,Baghuapali 22 Dasapala PHC(New) Banigochha PHC(New) ,Banigochha PHC(New) ,K.Khaman 23 Dasapala PHC(New) K.Khaman Nuagaon Nuagaon 24 Dasapala PHC(New) Kujamendhi PHC(New) ,Kujamendhi 25 Dasapala PHC(New) Chadheyapali PHC(New) ,Chadheyapali 26 Gania PHC(New) Adakata PHC(New) ,Adakata 27 Gania PHC(New) Chhamundia PHC(New) ,Chhamundia 28 Gania PHC(New) Rasanga PHC(New) ,Rasanga 29 Khandapada PHC(New) Kumbharapada PHC(New) ,Kumbharapada 30 Khandapada PHC(New) Rayatidolmara PHC(New) ,Rayatidolmara 31 Khandapada PHC(New) Banamalipur PHC(New) ,Banamalipur 32 Nayagarh PHC(New) Sankhoi PHC(New) ,Sankhoi 33 Nayagarh -

Odisha Diaries: the Struggle for Community Control Over Land, Forests and Natural Resources

Odisha diaries: the struggle for community control over land, forests and natural resources 1 Comments Author: Gaurav Madan @ Posted on: 9 Apr, 2015 No matter how much compensation is promised, companies will need ‘a social licence’ to conduct business on the land of the people Gaurav Madan For the past 20 years, local communities across the eastern Indian state of Odisha have engaged in numerous movements to protect their customary lands and forests against industrial and government interests. Several have captured global attention, documenting resistance from some of India’s most marginalised communities in the face of dispossession and displacement. Now, Odisha’s communities are mobilising once more to assert their rights over the resources that define their culture and survival, using modern technology and India’s Forest Rights Act of 2006 (FRA). Last month, in the village of Gunduribadi in Nayagarh district, I met with community members who have come together to legally document and claim their customary forest and grazing lands, fisheries, water bodies, medicinal plants, traditional knowledge, and sites of their livelihoods. Equipped with a government-issued map from 1983, GPS machines, and bottles of water, we set out under the blazing sun. We quickly crossed the administrative boundary of the village, and over the next six hours, scaled the steep slopes of the hills surrounding us. Along the way were landmarks erected by the British demarcating the land as a state-owned reserve forest. Today, the villagers are reclaiming this land as their own. The GPS-generated map will be the final seal on their recent application for a title recognising their land and forest rights under the FRA. -

Cuttack District, Odisha for River Sand

DISTRICT SURVEY REPORT (DSR) OF CUTTACK DISTRICT, ODISHA FOR RIVER SAND (FOR PLANNING & EXPLOITING OF MINOR MINERAL RESOURCES) ODISHA CUTTACK As per Notification No. S.O. 3611(E) New Delhi, 25th July, 2018 MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, FOREST AND CLIMATE CHANGE (MoEF & CC) COLLECTORATE, CUTTACK CONTENT SL NO DESCRIPTION PAGE NO 1 INTRODUCTION 2 OVERVIEW OF MINING ACTIVITIES IN THE DISTRICT 3 LIST OF LEASES WITH LOCATION, AREA AND PERIOD OF VALIDITY 4 DETAILS OF ROYALTY COLLECTED 5 DETAILS OF PRODUCTION OF SAND 6 PROCESS OF DEPOSIT OF SEDIMENTS IN THE RIVERS 7 GENERAL PROFILE 8 LAND UTILISATION PATTERN 9 PHYSIOGRAPHY 10 RAINFALL 11 GEOLOGY AND MINERAL WALTH LIST OF PLATES DESCRIPTION PLATE NO INDEX MAP OF THE DISTRICT 1 MAP SHOWING TAHASILS 2 ROAD MAP OF THE DISTRICT 3 MINERAL MAP OF THE DISTRICT 4 LEASE/POTENTIAL AREA MAP OF THE DISTRICT 5 1 | Page PLATE NO- 1 INDEX MAP ODISHA PLATE NO- 2 MAP SHOWING THE TAHASILS OF CUTTACK DISTRICT ......'-.._-.j l CUTTACK ,/ "---. ....•..... TEHSILMAP '~. Jajapur Angul Dhe:nkanal 1"' ~ . ..••.•..•....._-- .•.. "",-, Khordha ayagarh Tehs i I Bou ndmy -- Ceestnne PLATE NO- 3 MAP SHOWING THE MAJOR ROADS OF CUTTACK DISTRICT CUTTACK DISTRICT JAJPUR ANGUL LEGEND Natiol1Bl Highway NAYAGARH = Major Road - - - Rlliway .••••••. [JislJicl Bmndml' . '-- - - _. state Boullllary .-". River ..- Map ...l.~~.,. ~'-'-,.-\ @ [Ji8tricl HQ • 0Che-10Vil'I COjJyri!ll1tC 2013 www.mapsolindiiO:b<>.h (Updaled an 241h .Jenuary 201:l'l. • MajorlOVil'l PREFACE In compliance to the notification issued by the Ministry of Environment and Forest and Climate Change Notification no. S.O.3611 (E) NEW DELHI dated 25-07-2018 the preparation of district survey report of road metal/building stone mining has been prepared in accordance with Clause II of Appendix X of the notification. -

Pistrict: Nayagarh

DISTRICT ELEMENTARY EDUCATION PLAN 2002-10 AND ANNUAL PLAN 2002-03 PISTRICT: NAYAGARH NIEPA DC D11>49 GOVT OF ORISSA DEPARTMENT OF SCHOOL AND MASS EDUCATION '.ARVA SHIKSH ‘ ABHiYAN ORISSA PRIMARY EDUCATION PROGRAMME AUTHORITY ORISSA, BHUBANESWAR - 7S1001 , ""I; .SB ARVA 5HIKSHA ABWYAN DISTRICT ; NAYAGa I h C h a i n n a n S J KRUSHNA CHANDRA MOHAp*Y COLLECTOfi & DISTRICT W/^STSTRATE, NAVASAl M em ber Secretary SJ SANATAN PANDA 1>ISI'UK r INSl>FCTORC>F SCHOOLS, NAVAGARK CUM DlSTRIcrr PROIECT OFFICER, NAYAGARH M cnib _of_L) is t ric li’Jkiniiiii \ 1. Sri Biswaaath Singh Samaiita, Headmaster, Kiajhar UGM school. Sri Praffiilla Kumar Bariki, Sub-lnspecctor of School, Das illa(I) Sn Kama Krishna Nanda - Headmaster, Barapalli U(iME hool Sri Satchidananda Harichandan -Snb-lnspector of School Nayagaih (I) Sn C handramani Tripathy - H» ad mastei Kritlaspiir, U.G E. School Sri Durjodhan Sahoo- Headmaster- llafpatna E ) lool Sri (lopin uh Khadanira Head Master Kalikaprasad 11P(N ; ) School c 0 JS 1 H N _ T S Subjects Pages L i s t o f T a b l e & C o n t en t s 2-3 PLAN OVERVIEW 4 -7 CHAPTER -1 : DISTRICT PROFILE 8-17 CHAPTER-11 EDUCATIONAL PROFILE 18-69 CHAPTER-III : PLANNING PROCESS 70-91 CHAPTER -IV : PROBLEMS, ISSUES AND STRATEGIES 92-101 CHAPTER -V PLANNING FOR MAJOR INTERVENTION 10M38 WITH PHASING CHAPTER -VI • FDUCATION FOR URBAM DEPRIVED CHILDREN 139-141 CHAPTER-VII : BUDGET 8, COSTING 2002 -2010 142-158 CHAPTER-VIII • ANNUAL PLAN 2002 -2003 159-173 ABBREVIATIONS 174-176 \ \ Fablts ' S l~ Table No. -

Shri SK Swain, SIC, Odisha

Odisha Information Commission Block B-1, Toshali Bhawan, Satyanagar, Bhubaneswar-751007 * * * Weekly Cause List from 27/09/2021 to 01/10/2021 Cause list dated 27/09/2021 (Monday) Shri S. K. Swain, SIC, Odisha Court-IV (11 A.M.) Sl. Case No. Name of the Name of the Opposite party/ Respondent Remarks No Complainant/Appellant 1 S.A.-904/16 Debasish Hota District Court, Balangir district. 2 S.A.-905/16 Debasish Hota District Court, Balangir district. 3 S.A.-49/18 Madan Buyan Office of the District Panchayat Officer, Parlakhemundi, Gajapati district. 4 S.A.-54/18 Rajendra Baral Office of the B.D.O., Dharmasala Block, Jajpur district. 5 S.A.-57/18 Badri Prasad Mishra Office of the B.D.O., Kantapada Block, Cuttack district. 6 S.A.-74/18 Laxman Bhoi Office of the B.D.O., Golamunda Block, Kalahandi district. 7 S.A.-78/18 Niranjan Sing Office of the B.D.O., Nilgiri Block, Balasore district. 8 S.A.-81/18 Sangram Routray Directorate of Medical Education & Training, Odisha, Bhubaneswar. 9 S.A.-647/18 Deepak Kumar Mishra Ganjam Collectorate, Chhatrapur, Ganjam district. 10 S.A.-888/18 Mamta Tripathy Office of the Addl. District Magistrate, Bhubaneswar. 11 S.A.-889/18 Sanjaya Keshari Office of the Tahasildar, Nimapara Mohapatra Tahasil, Puri district. 12 S.A.-891/18 Jayakrushna Behera Office of the Project Director-Chief Engineer, Project Management Unit, Mega Lift Project, Bhubaneswar 13 S.A.-892/18 Jayakrushna Behera Water Resources Department, Govt. of Odisha, Bhubaneswar. 14 C.C.-145/17 Gajendra Agrawal Office of the Civil Judge Senior Division –cum- A.S.J., Kantabhanji, Balangir district.