The Ordeal of Carleton Stanley at Dalhousie University, 1943-1945 Barry Cahill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uncovering the Chains the Black and Aboriginal Slaves Who Helped Build New France

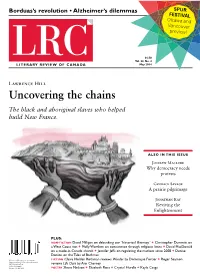

Borduas’s revolution • Alzheimer’s dilemmas SPUR FESTIVAL Ottawa and Vancouver preview! $6.50 Vol. 22, No. 4 May 2014 Lawrence Hill Uncovering the chains The black and aboriginal slaves who helped build New France. ALSO IN THIS ISSUE Jocelyn Maclure Why democracy needs protests Candace Savage A prairie pilgrimage Jonathan Kay Reviving the Enlightenment PLUS: NON-FICTION David Milligan on debunking our “historical illiteracy” + Christopher Dummitt on a West Coast riot + Molly Worthen on coexistence through religious limits + David MacDonald on a made-in-Canada church + Jennifer Jeffs on regulating the markets since 2008 + Denise Donlon on the Tales of Bachman Publications Mail Agreement #40032362 FICTION Claire Holden Rothman reviews Wonder by Dominique Fortier + Roger Seamon Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to LRC, Circulation Dept. reviews Life Class by Ann Charney PO Box 8, Station K Toronto, ON M4P 2G1 POETRY Shane Neilson + Elizabeth Ross + Crystal Hurdle + Kayla Czaga Literary Review of Canada 170 Bloor St West, Suite 710 Toronto ON M5S 1T9 email: [email protected] reviewcanada.ca T: 416-531-1483 • F: 416-531-1612 Charitable number: 848431490RR0001 To donate, visit reviewcanada.ca/support Vol. 22, No. 4 • May 2014 EDITOR Bronwyn Drainie [email protected] CONTRIBUTING EDITORS 2 Outthinking Ourselves 15 May Contain Traces Mark Lovewell, Molly Peacock, Robin A review of Enlightenment 2.0, by Joseph Heath A poem Roger, Anthony Westell Jonathan Kay Kayla Czaga ASSOCIATE EDITOR Judy Stoffman 4 Market Rules 18 Under the Volcano POETRY EDITOR A review of Transnational Financial Regulation A review of Wonder, by Dominique Fortier, Moira MacDougall after the Crisis, edited by Tony Porter translated by Sheila Fischman COPY EDITOR Jennifer Jeffs Claire Holden Rothman Madeline Koch 7 The Memory Thief 19 Making It ONLINE EDITORS Diana Kuprel, Jack Mitchell, A review of The Alzheimer Conundrum: A review of Life Class, by Ann Charney Donald Rickerd, C.M. -

1 PC1 Dalhousie University Photograph Collection PC1 18.30.1 Arms of Dalhousie N.D

PC1 Dalhousie University Photograph Collection PC1 32.30.1 A. Green, nursing n.d. Format and b&w print - 2 x 3 Notes PC1 34.5.1 A. L. Thurlow, faculty of law n.d. Format and b&w print - 3.5 x 5 Notes PC1 35.23.23-24 Aerial view of downtown Halifax - showing Scotia n.d. Square Format and b&w prints - 10 x 8 - 2 Notes PC1 2.6. Aerial views of campus n.d. Format and negatives Notes PC1 3.4.2? African Studies - Artifacts Format and negative Notes PC1 6.10.1-2 Alumni n.d. Format and b&w prints: 5x7 - 1, 8x10 - 1 Notes PC1 18.39.1-4 Alumni - Hockey n.d. Format and b&w print: 5x7 - 3, 5x8 - 1 Notes PC1 6.12.1-35 Alumni - 'There Stands Dalhousie' Film Clips n.d. Format and negative 35 mm - 92 frames; film clips 8mm - ca 910 frames Notes PC1 32.6.2 Anatomy department, S/S Plastic Format and b&w print -8.25 x 6.75 Notes PC1 15.8. Arab, Edward Francis Format and Notes BA 1935; LLB 1937 PC1 29.3. Archibald MacMechan n.d. Format and b&w print: 20x24 - 1 Notes PC1 15.13. Archibald, James Ross Format and Notes BA 1906; LLB 1908 1 PC1 Dalhousie University Photograph Collection PC1 18.30.1 Arms of Dalhousie n.d. Format and b&w print: 6x10 - 1 Notes Photograph is ripped in half. PC1 39.62. Army Training Grounds Format and b&w - 8x10 Notes PC1 9.23.1-4 Art Gallery n.d. -

Political Family Tree: Kinship in Canada’S Parliament

Canadian eview V olume 41, No. 1 Political Family Tree: Kinship in Canada’s Parliament 2 CANADIAN PARLIAMENTARY REVIEW/SPRING 2017 The current Mace of the Nova Scotia House of Assembly has been in use since it was gifted to the House on March 5, 1930 by Chief Justice Robert Edward Harris, the fourteenth Chief Justice of the Province and his wife. It is silver gilt, measuring four feet in height and weighs approximately 18 pounds. The four sides of the Mace depict the Royal Crown, the Armorial Achievement of Nova Scotia, the present (before Confederation) Great Seal of the Province, and the Speaker in his robes of office. Also found on the Mace is the floral emblem of Nova Scotia, the mayflower and the Scottish thistle. The Mace was manufactured in England by Elkington and Company, Limited. The Chief Justice and Mrs. Harris wanted to remain anonymous donors of the Mace, but the Premier, in agreeing to this, requested that someday a suitable inscription be made on the Mace. Thus, in his will the Chief Justice directed his executors to have the Mace engraved with the following inscription and to pay the cost for the engraving out of his estate: “This mace was presented to the House of Assembly of the Province of Nova Scotia by the Hon. Robert E. Harris, Chief Justice of Nova Scotia, and Mrs. Harris, March 1930”. The Chief Justice passed away on May 30, 1931. Annette M. Boucher Assistant Clerk 2 CANADIAN PARLIAMENTARY REVIEW/SPRING 2017 Kudryashka/Shutterstock.com/790257076 The Canadian Parliamentary Review was founded in 1978 to inform Canadian legislators about activities of the federal, provincial and territorial branches of the Canadian Region of the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association and to promote the study of and interest in Canadian parliamentary institutions. -

Robert Macgregor Dawson, 1895-1958

ROBERT MACGREGOR DAWSON, 1895-1958 THE death of Robert MacGregor Dawson on July 16, 1958, deprived the Uni versity of Toronto of a distinguished professor of political science and the country of its leading authority on the government of Canada. He died in his sixty-third year, hard at work on what he hoped would be his greatest contri bution to Canadian scholarship. It is difficult to convey to those who did not know him the impress that his vivid personality made on friends and colleagues and students. He was one of the most vital of men. He was born in the town of Bridgewater in Nova Scotia in 1895. His home was on the banks of the Lahave River almost at the exact spot where the salt water and the fresh water meet. His great grandfather had come out from Scotland and had later been drowned off Port Mouton in 1825. It was a fitting, if tragic, beginning for a Nova Scotian family. His grandfather and his father had prospered in the timber trade and in shipping, and then as general hard ware merchants. His mother was Mary MacGregor who was a grand-daughter of the famous Rev. Dr. MacGregor of Pictou County. Robert MacGregor Dawson (and he always used all three names) never had any quarrel with his start in life. He rejoiced and was proud. He was proud of his Scottish Presbyterian ancestors, he loved with an intense love the province where he was born, he never forgot the call of Lunenburg County or the sound and the smell of the sea. -

Robert Macgregor Dawson Fonds (MS-2-256, Box 1-33)

Dalhousie University Archives Finding Aid - Robert MacGregor Dawson fonds (MS-2-256, Box 1-33) Generated by the Archives Catalogue and Online Collections on January 23, 2017 Dalhousie University Archives 6225 University Avenue, 5th Floor, Killam Memorial Library Halifax Nova Scotia Canada B3H 4R2 Telephone: 902-494-3615 Email: [email protected] http://dal.ca/archives http://findingaids.library.dal.ca/robert-macgregor-dawson-fonds Robert MacGregor Dawson fonds Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Access points ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Dalhousie University Archives Page 2 MS-2-256, Box 1-33 Robert MacGregor Dawson fonds Summary information Repository: Dalhousie University Archives Title: Robert MacGregor Dawson fonds Reference code: MS-2-256, Box 1-33 Date: 1895-1962, 1920-1958 (date of creation) Language: English -

Download Download

The Governor General’s Literary Awards: English-Language Winners, 1936–2013 Andrew David Irvine* Entries are now being received for the Governor-General’s Annual Literary Awards for 1937, arranged by the Canadian Author’s Association. Medals will be given for the best books of fiction, poetry and general literature, respectively. The book must have been published during the calendar year 1937; and the author must be a Canadian. … There is no particular closing date. When the judges have read all the books, they will name the winners and that will end the matter. William Arthur Deacon1 This list2 of Governor General’s Literary Award–winning books differs from previous lists in several ways. It includes • five award-winning books from 1948, 1963, 1965, and 1984 (three in English and two in French) inadvertently omitted from previous lists; • the division of winning titles into historically accurate award categories; • a full list of books by non-winning finalists who have received cash prizes, a practice that began in 2002; • a full list of declined awards; • more detailed bibliographical information than can be found in most other lists; and 1* Andrew Irvine holds the position of professor and head of Economics, Philosophy, and Political Science at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan. Errata may be sent to the author at [email protected]. 11 William Arthur Deacon, The Fly Leaf, Globe and Mail, 9 April 1938, 15. 12 The list is split between two articles. The current article contains bibliographical information about English-language books that have won Governor General’s Literary Awards between 1936 and 2013. -

(Title of the Thesis)*

THE CANADIAN SOLDIER: COMBAT MOTIVATION IN THE CANADIAN ARMY, 1943-1945 by Robert Charles Engen A thesis submitted to the Department of History In conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada (June, 2014) Copyright ©Robert Charles Engen, 2014 Abstract This thesis is a study of the combat motivation and morale of infantrymen in the Canadian Army during the Second World War. Using battle experience questionnaires, censorship reports, statistical analyses, operational research, and other contemporary sources, this study offers a “big- picture” look at the human dimensions of warfare as experienced by Canadian infantrymen during the Italian and Northwest Europe campaigns of 1943 to 1945. The myths and realities of who the Canadian soldiers were provides the background, as does an exploration of their training and organization. Each core chapter explores one segment of the Canadian campaigns in Europe: the Sicilian and Italian campaign of 1943, the Italian campaign of 1944-45, the Normandy campaign of the summer of 1944, and the Northwest Europe campaign of 1944-45. Each of these chapters analyzes the force structure, behaviour in battle, morale, cohesion, and motivation of Canadian infantrymen during that particular segment of the campaign, setting them in comparison with one another to demonstrate continuities and change based upon shifting conditions, ground, and circumstances. In doing so, this thesis offers an original interpretation of Canadian combat motivation in the Second World War. Due to high infantry casualty rates, influxes of new reinforcements, and organizational turmoil, Canadian soldiers in many campaigns frequently fought as “strangers-in-arms” alongside unfamiliar faces. -

Anti-Catholicism and English Canadian Nationalism

ANTI-CATHOLICISM AND ENGLISH CANADIAN NATIONALISM “THIS TYPICAL OLD CANADIAN FORM OF RACIAL AND RELIGIOUS HATE”: ANTI-CATHOLICISM AND ENGLISH CANADIAN NATIONALISM, 1905-1965 By KEVIN ANDERSON, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy McMaster University © Copyright by Kevin Anderson, 2013 McMaster University DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (2013) Hamilton, Ontario (History) TITLE: “[T]his typical old Canadian form of racial and religious hate’: Anti-Catholicism and English Canadian Nationalism, 1905-1965 AUTHOR: Kevin Anderson, B.A. (York University) M.A. (York University) SUPERVISOR: Professor Michael Gauvreau NUMBER OF PAGES: ix, 425 ii Abstract This thesis examines the central influence of anti-Catholicism upon the construction of English Canadian nationalism during the first half of the twentieth century. Anti-Catholicism provided an existing rhetorical and ideological tradition and framework within which public figures, intellectuals, Protestant church leaders and other Canadians communicated their diverse visions of an ideal Canada. The study of anti- Catholicism problematizes the rigid separation that many scholars have posited between a conservative ethnic nationalism and a progressive civic nationalism. Often times these very civic values were inextricable from a context of Britishness. Hostility to Catholicism was not limited only to the staunchly Anglophile Conservative party or to fraternal organizations such as the Orange Order; indeed the importance of anti-Catholicism as a component of Canadian nationalism lies in its presence across the political and intellectual spectrum. Catholicism was perceived to inculcate values antithetical to British traditions of freedom and democracy. It was a medieval faith that stunted the “natural” development of its adherents, preventing them from becoming responsible citizens in a modern democracy. -

Chicago Reprise in the Champagne Years' of Canadian Sociology, 1935-1964 / by Thomas Palantzas

Lakehead University Knowledge Commons,http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca Electronic Theses and Dissertations Retrospective theses 1994 Chicago reprise in the Champagne Years' of Canadian sociology, 1935-1964 / by Thomas Palantzas. Palantzas, Thomas http://knowledgecommons.lakeheadu.ca/handle/2453/2432 Downloaded from Lakehead University, KnowledgeCommons National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1^1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Direction des acquisitions et Bibliographic Services Branch des services bibliographiques 395 \Wellington Street 395, tue Wellington Ottawa. Ontario Ottawa (Ontario) K1A 0N4 K1A 0N 4 NOTICE AVIS The quality of this microform is La qualité de cette microforme heavily dependent upon the dépend grandement de la qualité quality of the original thesis de la thèse soumise au submitted for microfilming. microfilmage. Nous avons tout Every effort has been made to fait pour assurer une qualité ensure the highest quality of supérieure de reproduction. reproduction possible. If pages are missing, contact the S’il manque des pages, veuillez university which granted the communiquer avec l’université degree. qui a conféré le grade. Some pages may have indistinct La qualité d’impression de print especially if the original certaines pages peut laisser à pages were typed with a poor désirer, surtout si les pages typewriter ribbon or if the originales ont été university sent us an inferior dactylographiées à l’aide d’un photocopy. ruban usé ou si l’université nous a fait parvenir une photocopie de qualité inférieure. Reproduction in full or in part of La reproduction, même partielle, this microform is governed by de cette microforme est soumise the Canadian Copyright Act, à la Loi canadienne sur le droit R.S.C.