The Story of Carey Marshman and Ward

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How the Vision of the Serampore Quartet Has Come Full Circle

Oxford Centre for Christianity and Culture, Centre for Baptist History and Heritage and Baptist Historical Society The heritage of Serampore College and the future of mission From the Enlightenment to modern missions: how the vision of the Serampore Quartet has come full circle John R Hudson 20 October 2018 The vision of the Serampore Quartet was an eighteenth century Enlightenment vision involving openness to ideas and respect for others and based on the idea that, for full understanding, you need to study both the ‘book of nature’ and the ‘book of God.’ Serampore College was a key component in the working out of this wider vision. This vision was superseded in Britain by the racist view that European civilisa- tion is superior and that Christianity is the means to bring civilisation to native peoples. This view had appalling consequences for native peoples across the Empire and, though some Christians challenged it, only in the second half of the twentieth century did Christians begin to embrace a vision more respectful of non-European cultures and to return to a view of the relationship between missionaries and native peoples more akin to that adopted by the Serampore Quartet. 1 Introduction Serampore College was not set up in 1818 as a theological college though ministerial training was to be part of its work (Carey et al., 1819); nor was it a major part, though it remains the most visible legacy of, the work of the Serampore Quartet.1 Rather it came as an outgrowth of the wider vision of the Serampore Quartet — a wider vision which, I will argue, arose from the eighteenth century Enlightenment and which has been rediscovered as the basis for mission in the second half of the twentieth century. -

Serampore: Telos of the Reformation

SERAMPORE: TELOS OF THE REFORMATION by Samuel Everett Masters B.A., Miami Christian College, 1989 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Religion at Reformed Theological Seminary Charlotte, North Carolina December, 2010 Accepted: ______________________________ Dr. Samuel Larsen, Project Mentor ii ABSTRACT Serampore: the Telos of the Reformation Samuel E. Masters While many biographies of missionary William Carey have been written over the last two centuries, with the exception of John Clark Marshman’s “The Life and Times of Carey, Marshman and Ward: Embracing the History of the Serampore Mission”, published in the mid-nineteenth century, no major work has explored the history of the Serampore Mission founded by Carey and his colleagues. This thesis examines the roots of the Serampore Mission in Reformation theology. Key themes are traced through John Calvin, the Puritans, Jonathan Edwards, and Baptist theologian Andrew Fuller. In later chapters the thesis examines the ways in which these theological themes were worked out in a missiology that was both practical and visionary. The Serampore missionaries’ use of organizational structures and technology is explored, and their priority of preaching the gospel is set against the backdrop of their efforts in education, translation, and social reform. A sense is given of the monumental scale of the work which has scarcely equaled down to this day. iii For Carita: Faithful wife Fellow Pilgrim iv CONTENTS Acknowledgements …………………………..…….………………..……………………...viii Chapter 1. INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………….9 The Father of Modern Missions ……………………………………..10 Reformation Principles ………………………………………….......13 Historical Grids ………………………………………………….......14 Serampore and a Positive Calvinism ………………………………...17 The Telos of the Reformation ………………………………………..19 2. -

'A Christian Benares' Orientalism, Science and the Serampore Mission of Bengal»

‘A Christian Benares’: Orientalism, science and the Serampore Mission of Bengal Sujit Sivasundaram Gonville and Caius College, Cambridge By using the case of the Baptist missionaries called the ‘Serampore Trio’—Rev. William Carey, Rev. William Ward and Rev. Joshua Marshman—this article urges that science and Christianity were intimately related in early nineteenth-century north India. The Serampore Baptists practised a brand of Christian and constructive orientalism, devoting themselves to the recovery of Sanskrit science and the introduction of European science into India. Carey established an impressive private botanical garden and was instrumental in the formation of the Agricultural Society of India. Ward, in his important account of Hinduism, argued that true Hindu science had given way to empiricism, and that Hindus had confused nature with the divine. The Serampore College formed by the trio sought to educate Indians with respect to both Sanskrit and European science, and utilised a range of scientific instruments and texts on science published in India. The College aimed to change the way its pupils saw the material world by urging experimen- tation rather than reverence of nature. The style of science practised at Serampore operated outside the traditional framework of colonial science: it did not have London as its centre, and it sought to bring indigenous traditions into a dialogue with European science, so that the former would eventually give way to the latter. The separation of science and Christianity as discrete bodies of intellectual en- deavour is alleged to be central to the emergence of modernity. Until recently, scholars cast modern science as a Western invention, which diffused across the world on the winds of empires, taking seed and bringing nourishment to all human- ity.1 Those who studied the spread of Christianity took a similar position in urging the transplantation of European values and beliefs wholesale by evangelists.2 These views have been decisively recast in the past two decades. -

Introduction: How Many of You Have Heard of William Carey, the Father Of

Introduction: How many of you have heard of William Carey, the father of modern missions? Ironically, growing up Catholic in India, I had never heard or read about him. At age 22 I started my first job as a journalist with The Statesman newspaper group, “directly descended from The Friend of India”. When at age 25 I left India for graduate school in the US I had a dream to return to launch a magazine of my own. That was not to be as I then settled in Canada. At age 33, after becoming a follower of Jesus, I started attending BBC. A lover of books, my first ministry was in the library, the same one over there. It was in this church library I finally read about William Carey who, together with his missionary colleagues, launched India’s first periodicals (including The Friend of India) in 1818 - yes, 200 years ago! At age 55, God gave me the vision to return to India to launch a bilingual magazine to give voice to India’s majority Backward Castes – the Dalits, the Tribals and the OBCs. Anybody who came into my editor’s office in New Delhi saw a poster with a picture of William Carey and his inspiring motto: Expect great things from God. Attempt great things for God! Just as I introduced many there to my hero, William Carey and his source of inspiration, I hope you will permit me to do so with you this morning. Let us pray … As a journalist I embraced what the “prince of preachers” Charles Spurgeon had said, we should have the Bible in one hand and the newspaper in the other! But before him, Carey had said, “To know the will of God, we need an open Bible and an open map.” In his humble cobbler’s workshop in England he had created a world map on which he noted details of the demographics of various nations that he gleaned from reading books by explorers including Captain Cook. -

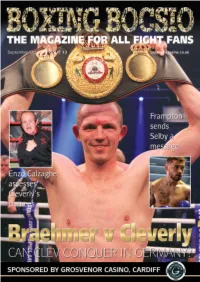

Bocsio Issue 13 Lr

ISSUE 13 20 8 BOCSIO MAGAZINE: MAGAZINE EDITOR Sean Davies t: 07989 790471 e: [email protected] DESIGN Mel Bastier Defni Design Ltd t: 01656 881007 e: [email protected] ADVERTISING 24 Rachel Bowes t: 07593 903265 e: [email protected] PRINT Stephens&George t: 01685 388888 WEBSITE www.bocsiomagazine.co.uk Boxing Bocsio is published six times a year and distributed in 22 6 south Wales and the west of England DISCLAIMER Nothing in this magazine may be produced in whole or in part Contents without the written permission of the publishers. Photographs and any other material submitted for 4 Enzo Calzaghe 22 Joe Cordina 34 Johnny Basham publication are sent at the owner’s risk and, while every care and effort 6 Nathan Cleverly 23 Enzo Maccarinelli 35 Ike Williams v is taken, neither Bocsio magazine 8 Liam Williams 24 Gavin Rees Ronnie James nor its agents accept any liability for loss or damage. Although 10 Brook v Golovkin 26 Guillermo 36 Fight Bocsio magazine has endeavoured 12 Alvarez v Smith Rigondeaux schedule to ensure that all information in the magazine is correct at the time 13 Crolla v Linares 28 Alex Hughes 40 Rankings of printing, prices and details may 15 Chris Sanigar 29 Jay Harris 41 Alway & be subject to change. The editor reserves the right to shorten or 16 Carl Frampton 30 Dale Evans Ringland ABC modify any letter or material submitted for publication. The and Lee Selby 31 Women’s boxing 42 Gina Hopkins views expressed within the 18 Oscar Valdez 32 Jack Scarrott 45 Jack Marshman magazine do not necessarily reflect those of the publishers. -

WAGE Women Under

WHO WAS WHO, 1897-1916 WAGE and Tendencies of German Transatlantic Henry Boyd, afterwards head of Hertford 1908 Enterprise, ; Aktiengesellschaften in Coll. Oxford ; Vicar of Healaugh, Yorkshire, den : Vereinigten Staaten ; Life of Carl Schurz, 1864-71. Publications The Sling and the 1908 Jahrbuch der ; Editor, Weltwirtschaft ; Stone, in 10 vols., 1866-93 ; The Mystery of Address : many essays. The University, Pain, Death, and Sin ; Discourses in Refuta- Berlin. Clubs : of of City New York ; Kaiserl. tion Atheism, 1878 ; Lectures on the Bible, Automobil, Berlin. [Died 28 June 1909. and The Theistic Faith and its Foundations, Baron VON SCHRODER, William Henry, D.L. ; 1881 ; Theism, or Religion of Common Sense, b. 1841 m. d. of ; 1866, Marie, Charles Horny, 1894 ; Theism as a Science of Natural Theo- Austria. High Sheriff, Cheshire, 1888. Ad- logy and Natural Religion, 1895 ; Testimony dress : The Rookery, Worlesden, Nantwich. of the Four Gospels concerning Jesus Christ, 11 all [Died June 1912. 1896 ; Religion for Mankind, 1903, etc. ; Horace St. editor VOULES, George, journalist ; Lecture on Cremation, Mr. Voysey was the of Truth b. ; Windsor, 23 April 1844 ; s. of only surviving founder of the Cremation Charles Stuart of also Voules, solicitor, Windsor. Society England ; he was for 25 years : Educ. private schools ; Brighton ; East- a member of the Executive Council to the bourne. Learned printing trade at Cassell, Homes for Inebriates. Recreations : playing & 1864 started for with children all Fetter, Galpin's, ; them ; games enjoyed except the Echo the first (1868), halfpenny evening chess, which was too hard work ; billiards at and it for until with paper, managed them they home daily, or without a companion ; sold it to Albert Grant, 1875 ; edited and walking and running greatly enjoyed. -

The Legacy of William Ward and Joshua and Hannah Marshman A

The Legacy of William Ward and Joshua and Hannah Marshman A. Christopher Smith magine an ellipse, with Calcutta and Serampore the focal youngermen whobecame his closest missionary colleagues also I points. A city and a suburban town in pre-Victorian Ben require notice. During the late eighteenth century Ward and the gal, separated from each other by twelve miles of the River Marshmanslived in important Britishports, in contrast to Carey, Hooghly. One British, one Danish. In those locations, a pioneer who never saw the sea before he sailed to India. Ward lived for band of British Baptists worked for several decades after 1800. several years in Hull, which was a key English port for the North Between those fixed points, they sailed several times a week for Sea and thus Germanic and Nordic Europe. The Marshmans various reasons-enough to make one wonder what sort of lived for decades in Bristol, which was a node of the triangular mission enterprise focused on that short axis. Thence developed Atlantic trade in African slaves and sugar. Ward and Marshman a tradition that would loom large in the history of the so-called sailed outto India together in 1799,the latterwith a wife and son, modern missionary movement. the other with neither, although the one who would become his The founding father of the Baptistmission at Serampore was wife also traveled with them on the American, India-bound ship William Carey.' An Englishman who sailed to Bengal in 1793, Criterion. By all accounts, both men had a promising missionary Carey keptresolutely to a twelve-mile stretchof river for 35 years career ahead of them withthe BaptistMissionarySociety (BMS).2 (after 1799) never departing from it. -

Church Bells

18 Church Bells. [Decem ber 7, 1894. the ancient dilapidated clook, which he described as ‘ an arrangement of BELLS AND BELL-RINGING. wheels and bars, black with tar, that looked very much like an _ agricultural implement, inclosed in a great summer-house of a case.’ This wonderful timepiece has been cleared away, and the size of the belfry thereby enlarged. The Towcester and District Association. New floors have been laid down, and a roof of improved design has been fixed b u s i n e s s in the belfry. In removing the old floor a quantity of ancient oaken beams A meeting was held at Towcester on the 17th ult., at Mr. R. T. and boards, in an excellent state of preservation, were found, and out of Gudgeon’s, the room being kindly lent by him. The Rev. R. A. Kennaway these an ecclesiastical chair has been constructed. The workmanship is presided. Ringers were present from Towcester, Easton Neston, Moreton, splendid, and the chair will be one of the ‘ sights ’ of the church. Pinkney, Green’s Norton, Blakesley, and Bradden. It was decided to hold The dedication service took place at 12.30 in the Norman Nave, and was the annual meeting at Towcester with Easton Neston, on May 16th, 189-5. well attended, a number of the neighbouring gentry and clergy being present. Honorary Members of Bell-ringing Societies. The officiating clergy were the Bishop of Shrewsbury, the Rev. A. G. S i e ,— I should be greatly obliged if any of your readers who are Secre Edouart, M.A. -

An Imperial Apostle? St Paul, Protestant Conversion and South Asian Christianity

An Imperial Apostle? St Paul, Protestant Conversion and South Asian Christianity SHINJINI DAS University of Cambridge ‘The account so carefully given by St Luke of the planting of the Churches in the Four Provinces … was certainly meant to be something more than the romantic history of an exceptional man like Paul, … it was intended to throw light on the path of those who should come after.’i … the answer comes with irresistible force that most of St Paul’s converts were born in an atmosphere certainly not better and in some respects, even worse that which we have to deal today in India or China.’ii ‘Admit then, that Paul was a necessary logical adjunct and consequent of Christ, as Moses was, indeed, his antecedent …If you cannot separate Paul from Christ, surely you cannot separate Paul from us. Are we not servants of Paul and Apostles of Jesus? Yes.’iii St Paul, the apostle who taught the Gospel of Christ to the first-century world, is seldom remembered either in the historiography of Indian Christianity or that of the British Empire in India. This is remarkable considering the regularity with which St Paul, his life and his letters were invoked by both Protestant missionaries and Indian Christian literature, including converts’ narratives. As the quotations above illustrate, Paul remained equally relevant for the two distinct nineteenth-century personalities. For Roland Allen, the late nineteenth- century Anglican missionary to China, the ancient saint’s activities provided the most robust blueprint against which to evaluate the future policies for missionaries in India and China. -

The Role of Christian Missionaries in Bengal

Bhatter College Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies Approved by the UGC (Serial No. 629, Subjects: Education, Broad category: Social Sciences) ISSN 2249-3301, Vol. VII, Number 1, 2017 Article url: www.bcjms.bhattercollege.ac.in/v7/n1/en-v7-01-07.pdf Article DOI: 10.25274/bcjms.v7n1.en-v7-01-07 The Genesis of English Education: the Role of Christian Missionaries in Bengal Thakurdas Jana Guest Lecturer, Department of English, Bhatter College, Dantan Abstract English Language Education has been an important factor for the uplift and development of an individual in this twenty first century when English is regarded as a lingua franca in the countries formerly colonized by the British. In every stratum of the society we need to learn English to have an easeful life. But the vernacular elementary education provided by the Pathsalas earlier was inadequate as observed by British observers like William Ward, William Adam and Francis Buchanan. In this situation, the Christian missionaries established many schools in West Bengal from 1819 onwards with the aim of providing western education to the mass of Bengal for their socio-cultural betterment. At that time Christian missionaries like Alexander Duff, William Carey, established many schools for providing English Education in and around Calcutta. Again George Pearce founded an English school at Durgapur in 1827. In the late 1820’s the missionaries achieved more success with the teaching of English. They made social and educational reform after Charter Act 1813 which permitted and financially helped them to spread English education in Bengal. This paper aims at unfolding the role played by those missionaries in spreading English education in Bengal. -

Chapter 3 Principles, Materials and Methods Used When Reconstructing

‘Under the shade I flourish’: An environmental history of northern Belize over the last three thousand five hundred years Elizabeth Anne Cecilia Rushton BMus BSc MSc Thesis submitted to the University of Nottingham for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2014 ABSTRACT Environmental histories are multi-dimensional accounts of human interaction with the environment over time. They observe how and when the environment changes (material environmental histories), and the effects of human activities upon the environment (political environmental histories). Environmental histories also consider the thoughts and feelings that humans have had towards the environment (cultural/ intellectual environmental histories). Using the methodological framework of environmental history this research, located in sub-tropical northern Belize, brings together palaeoecological records (pollen and charcoal) with archival documentary sources. This has created an interdisciplinary account which considers how the vegetation of northern Belize has changed over the last 3,500 years and, in particular, how forest resources have been used during the British Colonial period (c. AD 1800 – 1950). The palaeoecological records are derived from lake sediment cores extracted from the New River Lagoon, adjacent to the archaeological site of Lamanai. For over 3,000 years Lamanai was a Maya settlement, and then, more recently, the site of two 16th century Spanish churches and a 19th century British sugar mill. The British archival records emanate from a wide variety of sources including: 19th century import and export records, 19th century missionary letters and 19th and 20th century meteorological records and newspaper articles. The integration of these two types of record has established a temporal range of 1500 BC to the present. -

Hdnet Canada Schedule for Mon. April 16, 2012 to Sun. April 22, 2012 Monday April 16, 2012

HDNet Canada Schedule for Mon. April 16, 2012 to Sun. April 22, 2012 Monday April 16, 2012 1:00 PM ET / 10:00 AM PT 6:00 AM ET / 3:00 AM PT Nothing But Trailers IMAX - The Alps Sometimes the best part of the movie is the preview! So HDNet presents a half hour of Noth- In the air above Switzerland, on the sheer rock-and-ice wall known as the Eiger, an American ing But Trailers. See the best trailers, old and new in HDNet’s collection. climber is about to embark on the most perilous and meaningful ascent he has ever under- taken: an attempt to scale the legendary mountain that took his renowned father’s life. The 1:30 PM ET / 10:30 AM PT film celebrates the unsurpassed beauty of the Alps and the indomitable spirit of the people HDNet Music Discovery who live there. HDNet Music Discovery gives up-and-coming bands a chance to broadcast HD music videos in crystal clear true high definition and 5.1 Surround Sound on HDNet. 7:00 AM ET / 4:00 AM PT Cheers 1:55 PM ET / 10:55 AM PT From Beer To Eternity - The Cheers gang challenges the regulars from a rival bar to a bowling Chris Isaak - Greatest Hits tournament to avenge their losses in a variety of other sporting events. When another defeat Isaak graces the stage with a compelling set that spans his early years on through the new seems on the way, they produce an unexpected ace. millennium. The performance launches with “Dancin” from his debut.