Fabric of Belonging

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"Family Motacillidae" with Reference to Pakistan

Journal of Bioresource Management Volume 2 Issue 3 Article 10 Short Report: Description and Distribution of Wagtails "Family Motacillidae" with Reference to Pakistan Nadia Yousuf Bioresource Research Centre, Isalamabad, Pakistan Kainaat William Bioresource Research Centre, Islamabad, Pakistan Madeeha Manzoor Bioresource Research Centre, Islamabad, Pakistan, [email protected] Balqees Khanum Bioresource Research Centre, Islamabad, Pakistan Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/jbm Part of the Biodiversity Commons, and the Biology Commons Recommended Citation Yousuf, N., William, K., Manzoor, M., & Khanum, B. (2015). Short Report: Description and Distribution of Wagtails "Family Motacillidae" with Reference to Pakistan, Journal of Bioresource Management, 2 (3). DOI: 10.35691/JBM.5102.0034 ISSN: 2309-3854 online This Article is brought to you for free and open access by CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Bioresource Management by an authorized editor of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Short Report: Description and Distribution of Wagtails "Family Motacillidae" with Reference to Pakistan © Copyrights of all the papers published in Journal of Bioresource Management are with its publisher, Center for Bioresource Research (CBR) Islamabad, Pakistan. This permits anyone to copy, redistribute, remix, transmit and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes provided the original work and source is appropriately cited. Journal -

Consolidated List of HBL and Bank Alfalah Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments

Consolidated list of HBL and Bank Alfalah Branches for Ehsaas Emergency Cash Payments List of HBL Branches for payments in Punjab, Sindh and Balochistan ranch Cod Branch Name Branch Address Cluster District Tehsil 0662 ATTOCK-CITY 22 & 23 A-BLOCK CHOWK BAZAR ATTOCK CITY Cluster-2 ATTOCK ATTOCK BADIN-QUAID-I-AZAM PLOT NO. A-121 & 122 QUAID-E-AZAM ROAD, FRUIT 1261 ROAD CHOWK, BADIN, DISTT. BADIN Cluster-3 Badin Badin PLOT #.508, SHAHI BAZAR TANDO GHULAM ALI TEHSIL TANDO GHULAM ALI 1661 MALTI, DISTT BADIN Cluster-3 Badin Badin PLOT #.508, SHAHI BAZAR TANDO GHULAM ALI TEHSIL MALTI, 1661 TANDO GHULAM ALI Cluster-3 Badin Badin DISTT BADIN CHISHTIAN-GHALLA SHOP NO. 38/B, KHEWAT NO. 165/165, KHATOONI NO. 115, MANDI VILLAGE & TEHSIL CHISHTIAN, DISTRICT BAHAWALNAGAR. 0105 Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR KHEWAT,NO.6-KHATOONI NO.40/41-DUNGA BONGA DONGA BONGA HIGHWAY ROAD DISTT.BWN 1626 Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR-TEHSIL 0677 442-Chowk Rafique shah TEHSIL BAZAR BAHAWALNAGAR Cluster-2 BAHAWAL NAGAR BAHAWAL NAGAR BAZAR BAHAWALPUR-GHALLA HOUSE # B-1, MODEL TOWN-B, GHALLA MANDI, TEHSIL & 0870 MANDI DISTRICT BAHAWALPUR. Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR Khewat #33 Khatooni #133 Hasilpur Road, opposite Bus KHAIRPUR TAMEWALI 1379 Stand, Khairpur Tamewali Distt Bahawalpur Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR KHEWAT 12, KHATOONI 31-23/21, CHAK NO.56/DB YAZMAN YAZMAN-MAIN BRANCH 0468 DISTT. BAHAWALPUR. Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR-SATELLITE Plot # 55/C Mouza Hamiaytian taxation # VIII-790 Satellite Town 1172 Cluster-2 BAHAWALPUR BAHAWALPUR TOWN Bahawalpur 0297 HAIDERABAD THALL VILL: & P.O.HAIDERABAD THAL-K/5950 BHAKKAR Cluster-2 BHAKKAR BHAKKAR KHASRA # 1113/187, KHEWAT # 159-2, KHATOONI # 503, DARYA KHAN HASHMI CHOWK, POST OFFICE, TEHSIL DARYA KHAN, 1326 DISTRICT BHAKKAR. -

Health Facilities in Thatta- Sindh Province

PAKISTAN: Health facilities in Thatta- Sindh province Matiari Balochistan Type of health facilities "D District headquarter (DHQ) Janghari Tando "T "B Tehsil headquarter (THQ) Allah "H Civil hospital (CH) Hyderabad Yar "R Rural health center (RHC) "B Basic health unit (BHU) Jamshoro "D Civil dispensary (CD) Tando Las Bela Hafiz Road Shah "B Primary Boohar Muhammad Ramzan Secondary "B Khan Haijab Tertiary Malkhani "D "D Karachi Jhirck "R International Boundary MURTAZABAD Tando City "B Jhimpir "B Muhammad Province Boundary Thatta Pir Bux "D Brohi Khan District Boundary Khair Bux Muhammad Teshil Boundary Hylia Leghari"B Pinyal Jokhio Jungshahi "D "B "R Chatto Water Bodies Goth Mungar "B Jokhio Chand Khan Palijo "B "B River "B Noor Arbab Abdul Dhabeeji Muhammad Town Hai Palejo Thatta Gharo Thaheem "D Thatta D "R B B "B "H " "D Map Doc Name: PAK843_Thatta_hfs_L_A3_ "" Gujjo Thatta Shah Ashabi Achar v1_20190307 Town "B Jakhhro Creation Date: 07 March 2019 Badin Projection/Datum: GCS/WGS84 Nominal Scale at A3 paper size: 1:690,000 Haji Ghulammullah Pir Jo "B Muhammad "B Goth Sodho RAIS ABDUL 0 10 20 30 "B GHANI BAGHIAR Var "B "T Mirpur "R kms ± Bathoro Sindh Map data source(s): Mirpur GAUL, PCO, Logistic Cluster, OCHA. Buhara Sakro "B Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any Thatta opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Ghfbooksouthasia.Pdf

1000 BC 500 BC AD 500 AD 1000 AD 1500 AD 2000 TAXILA Pakistan SANCHI India AJANTA CAVES India PATAN DARBAR SQUARE Nepal SIGIRIYA Sri Lanka POLONNARUWA Sri Lanka NAKO TEMPLES India JAISALMER FORT India KONARAK SUN TEMPLE India HAMPI India THATTA Pakistan UCH MONUMENT COMPLEX Pakistan AGRA FORT India SOUTH ASIA INDIA AND THE OTHER COUNTRIES OF SOUTH ASIA — PAKISTAN, SRI LANKA, BANGLADESH, NEPAL, BHUTAN —HAVE WITNESSED SOME OF THE LONGEST CONTINUOUS CIVILIZATIONS ON THE PLANET. BY THE END OF THE FOURTH CENTURY BC, THE FIRST MAJOR CONSOLIDATED CIVILIZA- TION EMERGED IN INDIA LED BY THE MAURYAN EMPIRE WHICH NEARLY ENCOMPASSED THE ENTIRE SUBCONTINENT. LATER KINGDOMS OF CHERAS, CHOLAS AND PANDYAS SAW THE RISE OF THE FIRST URBAN CENTERS. THE GUPTA KINGDOM BEGAN THE RICH DEVELOPMENT OF BUILT HERITAGE AND THE FIRST MAJOR TEMPLES INCLUDING THE SACRED STUPA AT SANCHI AND EARLY TEMPLES AT LADH KHAN. UNTIL COLONIAL TIMES, ROYAL PATRONAGE OF THE HINDU CULTURE CONSTRUCTED HUNDREDS OF MAJOR MONUMENTS INCLUDING THE IMPRESSIVE ELLORA CAVES, THE KONARAK SUN TEMPLE, AND THE MAGNIFICENT CITY AND TEMPLES OF THE GHF-SUPPORTED HAMPI WORLD HERITAGE SITE. PAKISTAN SHARES IN THE RICH HISTORY OF THE REGION WITH A WEALTH OF CULTURAL DEVELOPMENT AROUND ISLAM, INCLUDING ADVANCED MOSQUE ARCHITECTURE. GHF’S CONSER- VATION OF ASIF KHAN TOMB OF THE JAHANGIR COMPLEX IN LAHORE, PAKISTAN WILL HELP PRESERVE A STUNNING EXAMPLE OF THE GLORIOUS MOGHUL CIVILIZATION WHICH WAS ONCE CENTERED THERE. IN THE MORE REMOTE AREAS OF THE REGION, BHUTAN, SRI LANKA AND NEPAL EACH DEVELOPED A UNIQUE MONUMENTAL FORM OF WORSHIP FOR HINDUISM. THE MOST CHALLENGING ASPECT OF CONSERVATION IS THE PLETHORA OF HERITAGE SITES AND THE LACK OF RESOURCES TO COVER THE COSTS OF CONSERVATION. -

Pdf | 951.36 Kb

P a g e | 1 Operation Updates Report Pakistan: Monsoon Floods DREF n° MDRPK019 GLIDE n° FL-2020-000185-PAK Operation update n° 1; Date of issue: 6/10/2020 Timeframe covered by this update: 10/08/2020 – 07/09/2020 Operation start date: 10/08/2020 Operation timeframe: 6 months; End date: 28/02/2021 Funding requirements (CHF): DREF second allocation amount CHF 339,183 (Initial DREF CHF 259,466 - Total DREF budget CHF 598,649) N° of people being assisted: 96,250 (revised from the initially planned 68,250 people) Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners currently actively involved in the operation: IFRC Pakistan Country Office is actively involved in the coordination and is supporting Pakistan Red Crescent Society (PRCS) in this operation. In addition, PRCS is maintaining close liaison with other in-country Movement partners: International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), German Red Cross (GRC), Norwegian Red Cross (NorCross) and Turkish Red Crescent Society (TRCS) – who are likely to support the National Society’s response. Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), Provincial Disaster Management Authorities (PDMAs), District Administration, United Nations (UN) and local NGOs. Summary of major revisions made to emergency plan of action: Another round of continuous heavy rains started in most part of the country on the week of 20 August 2020 until 3 September 2020 intermittently. The second round of torrential rains caused urban flooding in the Sindh province and flash flooding in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP). New areas have been affected by the urban flooding including the districts of Malir, Karachi Central, Karachi West, Karachi East and Korangi (Sindh), and District Shangla, Swat and Charsadda in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. -

Sindh Coast: a Marvel of Nature

Disclaimer: This ‘Sindh Coast: A marvel of nature – An Ecotourism Guidebook’ was made possible with support from the American people delivered through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The contents are the responsibility of IUCN Pakistan and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of USAID or the U.S. Government. Published by IUCN Pakistan Copyright © 2017 International Union for Conservation of Nature. Citation is encouraged. Reproduction and/or translation of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorised without prior written permission from IUCN Pakistan, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from IUCN Pakistan. Author Nadir Ali Shah Co-Author and Technical Review Naveed Ali Soomro Review and Editing Ruxshin Dinshaw, IUCN Pakistan Danish Rashdi, IUCN Pakistan Photographs IUCN, Zahoor Salmi Naveed Ali Soomro, IUCN Pakistan Designe Azhar Saeed, IUCN Pakistan Printed VM Printer (Pvt.) Ltd. Table of Contents Chapter-1: Overview of Ecotourism and Chapter-4: Ecotourism at Cape Monze ....... 18 Sindh Coast .................................................... 02 4.1 Overview of Cape Monze ........................ 18 1.1 Understanding ecotourism...................... 02 4.2 Accessibility and key ecotourism 1.2 Key principles of ecotourism................... 03 destinations ............................................. 18 1.3 Main concepts in ecotourism ................. -

The Geographic, Geological and Oceanographic Setting of the Indus River

16 The Geographic, Geological and Oceanographic Setting of the Indus River Asif Inam1, Peter D. Clift2, Liviu Giosan3, Ali Rashid Tabrez1, Muhammad Tahir4, Muhammad Moazam Rabbani1 and Muhammad Danish1 1National Institute of Oceanography, ST. 47 Clifton Block 1, Karachi, Pakistan 2School of Geosciences, University of Aberdeen, Aberdeen AB24 3UE, UK 3Geology and Geophysics, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Woods Hole, MA 02543, USA 4Fugro Geodetic Limited, 28-B, KDA Scheme #1, Karachi 75350, Pakistan 16.1 INTRODUCTION glaciers (Tarar, 1982). The Indus, Jhelum and Chenab Rivers are the major sources of water for the Indus Basin The 3000 km long Indus is one of the world’s larger rivers Irrigation System (IBIS). that has exerted a long lasting fascination on scholars Seasonal and annual river fl ows both are highly variable since Alexander the Great’s expedition in the region in (Ahmad, 1993; Asianics, 2000). Annual peak fl ow occurs 325 BC. The discovery of an early advanced civilization between June and late September, during the southwest in the Indus Valley (Meadows and Meadows, 1999 and monsoon. The high fl ows of the summer monsoon are references therein) further increased this interest in the augmented by snowmelt in the north that also conveys a history of the river. Its source lies in Tibet, close to sacred large volume of sediment from the mountains. Mount Kailas and part of its upper course runs through The 970 000 km2 drainage basin of the Indus ranks the India, but its channel and drainage basin are mostly in twelfth largest in the world. Its 30 000 km2 delta ranks Pakiistan. -

IN the SUPREME COURT of PAKISTAN (Appellate Jurisdiction)

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF PAKISTAN (Appellate Jurisdiction) Present: Mr. Justice Manzoor Ahmad Malik Mr. Justice Syed Mansoor Ali Shah C.P.1290-L/2019 (Against the Order of Lahore High Court, Lahore dated 31.01.2019, passed in W.P. No. 5898/2019) D. G. Khan Cement Company Ltd. ...….Petitioner(s) Versus Government of Punjab through its Chief Secretary, Lahore, etc. …….Respondent(s) For the petitioner(s): Mr. Salman Aslam Butt, ASC. For the respondent(s): Ms. Aliya Ejaz, Asstt. A.G. Dr. Khurram Shahzad, D.G. EPA. M. Nawaz Manik, Director Law, EPA. M. Younas Zahid, Dy. Director. Fawad Ali, Dy. Director, EPA (Chakwal). Kashid Sajjan, Asstt. Legal, EPA. Rizwan Saqib Bajwa, Manager GTS. Research Assistance: Hasan Riaz, Civil Judge-cum-Research Officer at SCRC.1 Date of hearing: 11.02.2021 JUDGEMENT Syed Mansoor Ali Shah, J.- The case stems from Notification dated 08.03.2018 (“Notification”) issued by the Industries, Commerce and Investment Department, Government of the Punjab (“Government”), under sections 3 and 11 of the Punjab Industries (Control on Establishment and Enlargement) Ordinance, 1963 (“Ordinance”), introducing amendments in Notification dated 17.09.2002 to the effect that establishment of new cement plants, and enlargement and expansion of existing cement plants shall not be allowed in the “Negative Area” falling within the Districts Chakwal and Khushab. 2. The petitioner owns and runs a cement manufacturing plant in Kahoon Valley in the Salt Range at Khairpur, District Chakwal and feels wronged of the Notification for the reasons, -

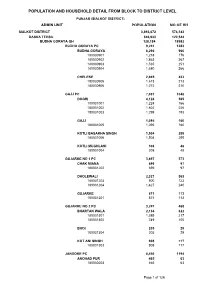

Sialkot Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (SIALKOT DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH SIALKOT DISTRICT 3,893,672 574,143 DASKA TEHSIL 846,933 122,544 BUDHA GORAYA QH 128,184 18982 BUDHA GORAYA PC 9,241 1383 BUDHA GORAYA 6,296 960 180030901 1,218 176 180030902 1,863 267 180030903 1,535 251 180030904 1,680 266 CHELEKE 2,945 423 180030905 1,673 213 180030906 1,272 210 GAJJ PC 7,031 1048 DOGRI 4,124 585 180031001 1,224 166 180031002 1,602 226 180031003 1,298 193 GAJJ 1,095 160 180031005 1,095 160 KOTLI BASAKHA SINGH 1,504 255 180031006 1,504 255 KOTLI MUGHLANI 308 48 180031004 308 48 GUJARKE NO 1 PC 3,897 573 CHAK MIANA 699 97 180031202 699 97 DHOLEWALI 2,327 363 180031203 900 123 180031204 1,427 240 GUJARKE 871 113 180031201 871 113 GUJARKE NO 2 PC 3,247 468 BHARTAN WALA 2,134 322 180031301 1,385 217 180031302 749 105 BHOI 205 29 180031304 205 29 KOT ANI SINGH 908 117 180031303 908 117 JANDOKE PC 8,450 1194 ANOHAD PUR 465 63 180030203 465 63 Page 1 of 126 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL PUNJAB (SIALKOT DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH JANDO KE 2,781 420 180030206 1,565 247 180030207 1,216 173 KOTLI DASO SINGH 918 127 180030204 918 127 MAHLE KE 1,922 229 180030205 1,922 229 SAKHO KE 2,364 355 180030201 1,250 184 180030202 1,114 171 KANWANLIT PC 16,644 2544 DHEDO WALI 6,974 1092 180030305 2,161 296 180030306 1,302 220 180030307 1,717 264 180030308 1,794 312 KANWAN LIT 5,856 854 180030301 2,011 290 180030302 1,128 156 180030303 1,393 207 180030304 1,324 201 KOTLI CHAMB WALI -

Multi- Hazard Vulnerability and Risk Assessment (MHVRA)

PAKISTAN: Multi- Hazard Vulnerability and Risk Assessment (MHVRA) Hunza Nagar China Ghizer Turkmenistan Chitral Gilgit Skardu Legend Khyber P. A. K Pakhtunkhwa Diamir Multi Hazard Ranking Ghanche Upper Astore Kohistan ! ! ! Lower Dir Swat ! Very High ! ! ! Dir Shangla Batagram ! Bajaur ! ! ! ! ! Neelum ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Agency ! ! Mansehra ! ! Jammu ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! High ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Malakand PA ! Mohmand Buner Tor Ghar Muzaffarabad ! ! ! ! Agency ! & ! Mardan ! Medium ! Charsadda ! Hattian! ! ! ! Swabi Abbottabad ! ! Peshawar ! Kashmir Haripur Bagh ! Low Haveli ! Khyber Agency Nowshera ! ! ! Poonch ! Kurram Orakzai FR Peshawar ! Sudhnoti ! Very Low ! Agency Agency FR Kohat ! ! I. A. K Afghanistan Islamabad ! Kohat ! Hangu Attock Kotli Rawalpindi ! ! ! ! Administrative Boundaries Mirpur ! ! Karak ! FR Bannu ! Bhimber ! ! ! International boundary Bannu Chakwal Jhelum FATA ! North ! FR Lakki Gujrat Waziristan Agency Marwat Lakki Mianwali Province boundary FR Marwat Mandi ! ! ! ! ! ! South Tank Bahauddin Sialkot Line of Control Waziristan Khushab Tank Narowal Agency NOTE: Multi Hazard includes Flood, Landslide, Sargodha Gujranwala Hafizabad Earthquake, Tsunami, Cyclone, Drought, Avalanche, Dera GLOF. Ismail FR Dera Khan Sheikhupura Bhakkar Chiniot Ismail Nankana Sheerani Khan Sahib Lahore Zhob Jhang Faisalabad Killa Layyah Kasur Saifullah Punjab Musakhel Toba Killa Pishin Map Doc Name: PAK816_NDMA_MHVRA_ Tek Singh Okara Abdullah Muzaffargarh Sahiwal A3_v1_L_20160627 Dera Ziarat Khanewal Ghazi Pakpattan Creation Date: 27 June -

Key Finding Report of PSLM

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyu iopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdf ghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcv bnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqw ertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuioKEY FINDINGS REPORT PAKISTAN SOCIAL AND LIVING pasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghSTANDARDS MEASUREMENT (PSLM) Survey jklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbDISTRICT LEVEL 2019-20 nmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwer tyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopa sdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjkl zxcvbnmrtyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqw Government of Pakistan ertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuioPakistan Bureau of Statistics, G-9/1,Islamabad Ministry of Planning Development pasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfgh& Special Initiatives PSLM – 2019-20 PAKISTAN SOCIAL AND LIVING STANDARDS MEASUREMENT SURVEY (2019-20) District Level Survey Government of Pakistan Pakistan Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Planning Development & Special Initiatives May - 2021 www.pbs.gov.pk TABLE OF CONENT PSLM 2019-20 TABLE OF CONTENT FOREWORD………………………………………………………………………………………...…….. i PREFACE…………………………………………………………………………………………...…….. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ……………………………………………………………………………..... iii LIST OF OFFICERS………………………………………………………………………………….…. iv SDG INDICATORS……………………………………………………………………………………… v SAMPLE DESIGN…………………………………………………………………………….………… 1 EDUCATION………………………………………………………………………………………..…… 2 INFORMATION COMMUNICATION AND TECHNOLOGY……………………………………...... 16 HEALTH…………………………………………………………………… ………………………..…. 21 HOUSING, -

Floods in Pakistan No 20

Pakistan Health Cluster Floods in Pakistan No 20. 12 October 2010 Waiting for Health Services at an IDP camp in Dadu. Photo by Dr Guido Sabatinelli HIGHLIGHTS • WHO’s epidemiological bulletin will now be published on a weekly bases presenting trends, while daily information will be distributed only to concerned staff. • Ongoing malaria surveillance in collaboration with the Malaria Control Programme has identified the following districts with high incidence of Falciparum cases: Layyah, Rajanpur, DG Khan and Muzaffargarh in Punjab; Jacobabad, Larkana, Thatta and Khairpur in Sindh; Naseerabad, Sibi, Zhob and Jhal Magsi in Bal uchistan. • New cases of Dengue and Crimean -Congo haemorrhagic fever (CCHF) were reported last week. The MoH assisted by WHO is planning control measures. • Over the past week, ten new poliomyelitis (pol io) cases were reported, seven of which are from flood-affected districts. • Plans for Early recovery for flood affected districts becoming a priority for the Health Cluster. • Health cluster partners (key NGOs/UN agencies) have been identified to lead health cluster coordination activities in 5 most affected districts (Mianwali, Layyah, Muzaffargarh, DG Khan and Rajanpur ). Situation overview While substantial areas in Sindh, in particular Dadu and Qamber Shahdkot, are still flooded, access to northern districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) continues to improve; the flood is visible only in the destruction it has left behind. As the weeks go by, the ways in which the flood has affected the different areas of the country are becoming more apparent. Partners are designing and implementing activities that respond to these diverse needs and situations. According to OCHA, in KP and Punjab most internally displaced people (IDPs) have returned home.