Minority Concentration District Project Nicobar, Andaman and Nicobar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Imperializing Norden

Neumann, Iver B. Imperializing Norden Article (Accepted version) (Refereed) Original citation: Neumann, Iver B. (2014) Imperializing Norden. Cooperation and Conflict, 49 (1). pp. 119-129. ISSN 0010-8367 DOI: 10.1177/0010836714520745 © 2014 by Nordic International Studies Association, SAGE Publications This version available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/56565/ Available in LSE Research Online: April 2016 LSE has developed LSE Research Online so that users may access research output of the School. Copyright © and Moral Rights for the papers on this site are retained by the individual authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may download and/or print one copy of any article(s) in LSE Research Online to facilitate their private study or for non-commercial research. You may not engage in further distribution of the material or use it for any profit-making activities or any commercial gain. You may freely distribute the URL (http://eprints.lse.ac.uk) of the LSE Research Online website. This document is the author’s final accepted version of the journal article. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. Imperializing Norden.1 Cooperation and Conflict 49 (1): 119-129 (2014) Epilogue for a special issue on Post-Imperial Sovereignty Games in Norden Iver B. Neumann, [email protected] Abstract The two pre-Napoleonic Nordic polities are best understood as empires. Drawing on recent analytical and historical scholarship on empires, I argue that 17th and 18th-century Denmark, on which the piece concentrates, was very much akin to other European empires that existed at the time. -

(Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, for the Year 2009

REPORT U/s 21 (4) OF THE SCHEDULED CASTES AND THE SCHEDULED TRIBES (PREVENTION OF ATROCITIES) ACT, 1989, FOR THE YEAR 2009 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF SOCIAL JUSTICE AND EMPOWERMENT CONTENTS CHAPTER TITLE PAGE NO. NO. 1 INTRODUCTION 1-4 2 STRUCTURE AND MECHANISM ESTABLISHED FOR 5-9 IMPLEMENTATION OF THE SCHEDULED CASTES AND THE SCHEDULED TRIBES (PREVENTION OF ATROCITIES) ACT, 1989. 3 ACTION BY THE POLICE AND THE COURTS IN CASES 10-14 REGISTERED UNDER THE SCHEDULED CASTES AND THE SCHEDULED TRIBES (PREVENTION OF ATROCITIES) ACT, 1989. 4. MEASURES TAKEN BY GOVERNMENT OF INDIA 15-19 5. MEASURES TAKEN BY STATE GOVERNMENTS AND UNION 20-87 TERRITORY ADMINISTRATIONS STATE GOVERNMENTS 5.1 ANDHRA PRADESH 20-27 5.2 ARUNACHAL PRADESH 28 5.3 ASSAM 29-30 5.4 BIHAR 31-33 5.5 CHHATTISGARH 35-36 5.6 GOA 37-38 5.7 GUJARAT 39-42 5.8 HARYANA 43-44 5.9. HIMACHAL PRADESH 45-46 5.10 KARNATAKA 47-49 5.11 KERALA 50-51 5.12 MADHYA PRADESH 52-56 5.13 MAHARASHTRA 57-60 5.14 MANIPUR 61 5.15 ODISHA 62-64 5.16 PUNJAB 65-66 5.17 RAJASTHAN 67-69 5.18 SIKKIM 70-71 5.19 TAMIL NADU 72-75 5.20 TRIPURA 76 5.21 UTTAR PRADESH 77-78 5.22 WEST BENGAL 79-80 UNION TERRITORY ADMINISTRATIONS 5.23 ANDAMAN & NICOBAR ISLANDS 81 5.24 CHANDIGARH 82 5.25 DAMAN & DIU 83 5.26 NATIONAL CAPITAL TERRITORY OF DELHI 84 5.27 LAKSHADWEEP 85 5.28 PUDUCHERRY 86 5.29 OTHER STATE GOVERNMENTS/UNION TERRITORY 87 ADMINISTRATIONS ANNEXURES I EXTRACT OF SECTION 3 OF THE SCHEDULED CASTES AND 88-90 THE SCHEDULED TRIBES (PREVENTION OF ATROCITIES) ACT, 1989. -

ISO Country Codes

COUNTRY SHORT NAME DESCRIPTION CODE AD Andorra Principality of Andorra AE United Arab Emirates United Arab Emirates AF Afghanistan The Transitional Islamic State of Afghanistan AG Antigua and Barbuda Antigua and Barbuda (includes Redonda Island) AI Anguilla Anguilla AL Albania Republic of Albania AM Armenia Republic of Armenia Netherlands Antilles (includes Bonaire, Curacao, AN Netherlands Antilles Saba, St. Eustatius, and Southern St. Martin) AO Angola Republic of Angola (includes Cabinda) AQ Antarctica Territory south of 60 degrees south latitude AR Argentina Argentine Republic America Samoa (principal island Tutuila and AS American Samoa includes Swain's Island) AT Austria Republic of Austria Australia (includes Lord Howe Island, Macquarie Islands, Ashmore Islands and Cartier Island, and Coral Sea Islands are Australian external AU Australia territories) AW Aruba Aruba AX Aland Islands Aland Islands AZ Azerbaijan Republic of Azerbaijan BA Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina BB Barbados Barbados BD Bangladesh People's Republic of Bangladesh BE Belgium Kingdom of Belgium BF Burkina Faso Burkina Faso BG Bulgaria Republic of Bulgaria BH Bahrain Kingdom of Bahrain BI Burundi Republic of Burundi BJ Benin Republic of Benin BL Saint Barthelemy Saint Barthelemy BM Bermuda Bermuda BN Brunei Darussalam Brunei Darussalam BO Bolivia Republic of Bolivia Federative Republic of Brazil (includes Fernando de Noronha Island, Martim Vaz Islands, and BR Brazil Trindade Island) BS Bahamas Commonwealth of the Bahamas BT Bhutan Kingdom of Bhutan -

Colonies and Metropole

COLONIES AND METROPOLE Michael Bregnsbo, Niels Brimnes, Anne Folke Henningsen, Poul Erik Olsen, Mik- kel Venborg Pedersen og Uffe Østergård Danmark – En kolonimagt Gads Forlag, 2017, 480 pages Colonial history is a ield that has developed rapidly in the Nordic countries since the start of the new millennium.1 Old myths of the Nordic countries as the inno- cent bystanders of European colonialism have been comprehensively challenged, as have ideas of the Nordic countries as “good colonists”, pursuing a more benign form of overseas expansion compared to the major European powers like Britain, France and Germany.2 As Magdalena Naum and Jonas M. Nordin wrote in their in- troduction to an anthology published in 2013, “colonialism in its many forms was part of the very fabric of the North European societies”, driven by the same mo- tives as those operating in other parts of Europe: the pursuit of proit and politi- cal power.3 That the colonial ambitions of the Danish and Swedish kingdoms were only ever partly realised does not diminish the importance of researching them, and historians have also studied Nordic participation in informal colonialism, in- cluding trade and missionary activities.4 The reasons for this interest are not hard to ind. The idea of Norden as a Euro- pean periphery is no longer sustainable, if indeed it ever was. Almost half a cen- tury of mass immigration, including from non-European societies, and the deba- tes about ethnic pluralism and cultural “otherness” that this has provoked, have focused attention on this further. Within history as an academic discipline, the rising interest in transnational and global history, with its emphasis on the im- portance of links, connections and interactions across national borders, has also had an inluence.5 As Gunlög Fur has noted, however, where the Nordic countries 1 Also in ields other than history: see for example Larsen and Thisted, ‘Preface’, on postco- lonial studies in Denmark. -

Friday 22 May 2015 Issued By

Friday 22nd May 2015 (For the period 22nd to 26th May 2015) Issued by National Agrometeorological Advisory Service Centre, Agricultural Meteorology Division, India Meteorological Department, Shivajinagar, Pune. Monsoon Watch The Northern Limit of Monsoon (NLM) continue to pass through Lat 05.0°N/ Long. 79.0°E, Hambantota (Srilanka), Lat. 10.0°N/ Long. 86.0°E, Lat. 13.0°N / Long. 89.0°E and Lat. 18.0°N / Long. 95.0°E. Standardised Precipitation Index Four Weekly for the Period 23rd April to 20th May 2015 Extremely/severely wet conditions experienced in many districts of Tamil Nadu & Puducherry and Karnataka; Purulia district of West Bengal; Bokaro district of Jharkhand; Gopalganj district of Bihar; Ballia district of Uttar Pradesh; Gwalior, Satna, Shahdol districts of Madhya Pradesh; Nanded district of Maharashtra; Durg, Rajnandgaon, Surguja districts of Chhattisgarh; Palakkad, Thiruvananthapuram districts of Kerala. Severely/moderately dry conditions experienced in Nicobar district of Andaman & Nicobar Islands; Nagaon, Karbi Anglong, Bongaigaon, Lakhimpur districts of Assam; Changlang, East Kameng districts of Arunachal Pradesh; Imphal East district of Manipur; Kohima district of Nagaland; Nasik district of Maharashtra. Rest of the country experienced moderately wet/mildly dry/wet conditions. Contour maps for Mean Maximum and Minimum Temperature and their anomaly for the week ending on 20.05.2015 Actual Mean Maximum Temperature (oC) in India Mean Maximum Temperature (oC) Anomaly in for the week ending 20.05.2015 India for the week ending 20.05.2015 Mean maximum temperature was above 400C over Mean maximum temperature were below normal by 2 to Rajasthan, many parts of Gujarat, West Madhya Pradesh, 60C over Tamil Nadu, many parts of Chhattisgarh, some Vidarbha, some parts of Uttar Pradesh, East Madhya parts of East Madhya Pradesh, Vidarbha, Rayalaseema, Pradesh, Madhya Maharashtra, Marathwada, Telangana South Interior Karnataka and isolated pockets of Coastal and isolated pockets of Bihar, Jharkhand and Odisha. -

What Is the Importance of Islands to Environmental Conservation?

Environmental Conservation (2017) 44 (4): 311–322 C Foundation for Environmental Conservation 2017 doi:10.1017/S0376892917000479 What is the importance of islands to environmental THEMATIC SECTION Humans and Island conservation? Environments CHRISTOPH KUEFFER∗ 1 AND KEALOHANUIOPUNA KINNEY2 1Institute of Integrative Biology, ETH Zurich, Universitätsstrasse 16, CH-8092 Zurich, Switzerland and 2Institute of Pacifc Islands Forestry, US Forest Service, 60 Nowelo St. Hilo, HI, USA Date submitted: 15 May 2017; Date accepted: 8 August 2017 SUMMARY islands of the world’s oceans, we cover both islands close to continents and others isolated far out in the oceans, and the This article discusses four features of islands that make full range from small to very large islands. Small and isolated them places of special importance to environmental islands represent unique cultural and biological values and the conservation. First, investment in island conservation environmental challenges of insularity in its most pronounced is both urgent and cost-effective. Islands are form. However, as we will demonstrate, all islands and island threatened hotspots of diversity that concentrate people share enough come concerns to consider them together unique cultural, biological and geophysical values, (Baldacchino 2007; Royle 2008; Gillespie & Clague 2009; and they form the basis of the livelihoods of Baldacchino & Niles 2011; Royle 2014). millions of islanders. Second, islands are paradigmatic Islands are hotspots of cultural, biological and geophysical places of human–environment relationships. Island diversity, and as such they form the basis of the livelihoods livelihoods have a long tradition of existing within of millions of islanders (Menard 1986; Nunn 1994; Royle spatial, ecological and ultimately social boundaries 2008; Gillespie & Clague 2009; Royle 2014; Kueffer et al. -

India's Andaman and Nicobar Islands

www.rsis.edu.sg No. 135 – 2 June 2016 RSIS Commentary is a platform to provide timely and, where appropriate, policy-relevant commentary and analysis of topical issues and contemporary developments. The views of the authors are their own and do not represent the official position of the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, NTU. These commentaries may be reproduced electronically or in print with prior permission from RSIS and due recognition to the author(s) and RSIS. Please email: [email protected] for feedback to the Editor RSIS Commentary, Yang Razali Kassim. India’s Andaman and Nicobar Islands: Growing Regional Significance By Nazia Hussain Synopsis As China expands its maritime reach in the Indian Ocean, the Andaman and Nicobar Islands off the coast of India have gone high up on the priority list for New Delhi’s defence policy. The Modi government should develop a plan of action to tap the security and economic potential of the islands. Commentary LOCATED AT the juncture of the Bay of Bengal and the Andaman Sea, a group of 572 islands (of which only 37 are inhabited)—the Andaman and Nicobar Island chain—straddles the busiest trade routes in the world, spanning 450 nautical miles and sits strategically at the entrance of the Malacca Straits. Although administered by India, these islands have greater proximity to Southeast Asia—Myanmar, Indonesia and Thailand—than to the Indian mainland. This geographical distance from the mainland has long been a reason for New Delhi to neglect the islands, treating it only as a distant sentinel outpost. -

India's Missile Programme and Odisha : a Study

January - 2015 Odisha Review India's Missile Programme and Odisha : A Study Sai Biswanath Tripathy India’s missile and nuclear weapons programs First, there must be an open, uninhabited stretch have evolved as elements of its strategic response of land or water (several hundred kilometers long) to 68 years of wars and skirmishes it has fought ‘down range.’ Second, the site ideally, must allow with Pakistan and with China. Deep tensions and for longitudinal launch. The first requirement is to mistrust in the sub-continent continue unabated ensure that a malfunction during the launch stage to the present. India’s defeat by China in the 1962 does not cause damage to civilian lives and border war, probably more than any other event, property. Rocket propellant is highly explosive galvanized its leadership to build indigenous missile and if it does explode during the launch stage, and “threshold” nuclear weapons capabilities as burning fuel and metal fragments are sprayed over a credible deterrent against attack by China, and vast areas. Often, rockets fail to take off along to attain military superiority over Pakistan. the planned trajectory and have to be destroyed by the range safety officer. In this case too, the As far back as in November 1978, the· effects are so devastating that most launch sites government had set up a Committee to identify a around the world are consequently located on a site for the establishment of an instrumented test coast. range. A group of experts had surveyed a number The Bay of Bengal provides an ideal of sites, including the Sunderbans (West Bengal), stretch of sea over which missiles can be fired. -

Annual Report on Vital Statistics of India Based On

VITAL STATISTICS OF INDIA BASED ON THE CIVIL REGISTRATION SYSTEM 2010 OFFICE OF THE REGISTRAR GENERAL, INDIA MINISTRY OF HOME AFFAIRS VITAL STATISTICS DIVISION WEST BLOCK-I, R. K. PURAM NEW DELHI- 110066 ENSURE REGISTRATION OF EVERY BIRTH AND DEATH PREFACE The Civil Registration System (CRS) may be defined as a unified process of continuous, permanent and compulsory recording of the vital events and characteristics thereof, as per legal requirements in the country. In India, the Civil Registration System covers registration of births and deaths only. It provides the best source of information on the vital rates at all levels. 2. This issue of the Report on ‘Vital Statistics of India based on the Civil Registration System’ for the year 2010 provides an overview of the working of the Civil Registration System (CRS) in the country and presents a compilation of data on registered births, deaths and infant deaths with rural-urban & sex- wise break-up and sex ratio at birth based on Civil Registration Records. Ideally, an Annual Report on vital statistics containing more detailed information should have been brought out. However, due to non-availability of Annual Reports from some of the major States and limited availability of information contained in the Annual Reports of some of other States, the report for the year 2010 containing key information has been brought out for the convenience of users. An attempt has been made to present more detailed analysis as compared to previous Reports. 3. The publication is divided into two parts. Part I provides a brief review of the Civil Registration System and contains a summary analysis of data on registered births, deaths, infant deaths and sex ratio at birth at State level. -

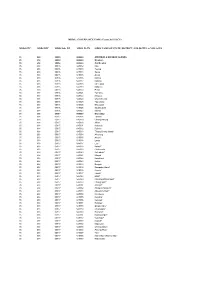

MDDS STC MDDS DTC MDDS Sub DT MDDS PLCN MDDS NAME of STATE, DISTRICT, SUB-DISTTS. & VILLAGES MDDS E-GOVERNANCE CODE (Census

MDDS e-GOVERNANCE CODE (Census 2011 PLCN) MDDS STC MDDS DTC MDDS Sub_DT MDDS PLCN MDDS NAME OF STATE, DISTRICT, SUB-DISTTS. & VILLAGES 35 000 00000 000000 ANDAMAN & NICOBAR ISLANDS 35 638 00000 000000 Nicobars 35 638 05916 000000 Car Nicobar 35 638 05916 645012 Mus 35 638 05916 645013 Teetop 35 638 05916 645014 Sawai 35 638 05916 645015 Arong 35 638 05916 645016 Kimois 35 638 05916 645017 Kakana 35 638 05916 645018 IAF Camp 35 638 05916 645019 Malacca 35 638 05916 645020 Perka 35 638 05916 645021 Tamaloo 35 638 05916 645022 Kinyuka 35 638 05916 645023 Chuckchucha 35 638 05916 645024 Tapoiming 35 638 05916 645025 Big Lapati 35 638 05916 645026 Small Lapati 35 638 05916 645027 Kinmai 35 638 05917 000000 Nancowry 35 638 05917 645028 Tahaila 35 638 05917 645029 Chongkamong 35 638 05917 645030 Alhiat 35 638 05917 645031 Kuitasuk 35 638 05917 645032 Raihion 35 638 05917 645033 Tillang Chong Island* 35 638 05917 645034 Aloorang 35 638 05917 645035 Aloora* 35 638 05917 645036 Enam 35 638 05917 645037 Luxi 35 638 05917 645038 Kalara* 35 638 05917 645039 Chukmachi 35 638 05917 645040 Safedbalu* 35 638 05917 645041 Minyuk 35 638 05917 645042 Kanahinot 35 638 05917 645043 Kalasi 35 638 05917 645044 Bengali 35 638 05917 645045 Bompoka Island* 35 638 05917 645046 Jhoola* 35 638 05917 645047 Jansin* 35 638 05917 645048 Hitlat* 35 638 05917 645049 Mavatapis/Maratapia* 35 638 05917 645050 Chonghipoh* 35 638 05917 645051 Sanaya* 35 638 05917 645052 Alkaipoh/Alkripoh* 35 638 05917 645053 Alhitoth/Alhiloth* 35 638 05917 645054 Katahuwa* 35 638 05917 645055 -

AFFNO EXNO School Name 100001 AP06012 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA

AFFNO EXNO School Name 100001 AP06012 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA NO 1 GOLCONDA HYDERABAD AP 100002 AP06045 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA PICKET SECUNDERABAD AP 100003 AP06047 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA TRIMULGHERRY SECUNDERABAD AP 100004 AP06021 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA NO.1 UPPAL HYDERABAD AP 100005 AP06027 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA KANCHANBAGH HYDERABAD AP 100006 AP06022 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA 1 AFA DUNDIGAL HYDERABAD 100007 AP06053 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA RAMNAGAR AREA TIRUPATI AP 100008 AP06060 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA MALKAPURAM VISAKHAPATNAM AP 100009 AP06058 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA NO 1 SRI VIJAYA NGR VIZAG AP 100010 AP06034 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA NO 1 RAMAGUNDAM KARIMNAGAR 100011 AP06010 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA CRPF BARKAS HYDERABAD AP 100012 AP06056 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA WALTAIR VISAKHAPATNAM AP 100013 AP06051 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA BOLARUM SECUNDERABAD AP 100014 AP06006 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA NALLAPADU GUNTUR A.P 100015 AP06057 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA NO 1 NAUSENABAUGH VIZAG. AP 100016 AP06020 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA NO 2 UPPAL HYDERABAD AP 100017 AP06046 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA AFS HAKIMPET SECUNDERABAD AP 100018 AP06035 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA NTPC RAMAGUNDAM KARIMNAGAR AP 100019 AP06013 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA AFS BEGUMPET HYDERABAD AP 100020 AP06064 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA STEEL PLANT VISAKHAPATNAM AP 100021 AP06077 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA O F EDDUMAILARAM MEDAK AP 100022 AP06059 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA NO 2 SRI VIJAY NGR VIZAG. AP 100023 AP06069 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA YERRAGUNTLA CUDDAPAH A.P 100024 AP06100 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA PRABHAT NAGAR GUNTAKAL A.P 100025 AP06080 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA SHIVARAMPALLY HYDERABAD AP 100026 AP06085 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA NO.2 GOLCONDA HYDERABAD AP 100027 AP06091 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA AFS SURYALANKA BAPATLA AP 100028 AP06108 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA N.A.D VISAKHAPATNAM A.P 100029 AP06119 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA CCI TOWNSHIP ADILABAD A.P 100030 AP06109 D A V PUBLIC SCHOOL CCI TANDUR R R DIST A.P 100031 AP06110 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA GACHIBOWLI HYDERABAD A.P 100032 AP06111 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA B CAMP P.O KURNOOL A.P 100033 AP06154 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA NO 2 SETTIPALLY TIRUPATHI AP 100034 AP06120 KENDRIYA VIDYALAYA No.2 NAUSENABAGH VIZAG A.P 100035 AP06121 K.V. -

Friday 20 January 2017

Friday 20th January 2017 (For the period 20th to 24th January 2017) Weblink For District AAS Bulletin: http://www.imdagrimet.gov.in/node/3545 State Composite AAS Bulletin: http://www.imdagrimet.gov.in/node/3544 1 Contour maps for Mean Maximum and Minimum Temperature and their anomaly for the week ending on 18.01.2017 Actual Mean Maximum Temperature (oC) in India for Mean Maximum Temperature (oC) Anomaly in India for the week ending 18.01.2017 the week ending 18.01.2017 Mean maximum temperature was between 32 to 360C Mean maximum temperature was above normal by 2 to over many parts of Lakshadweep, Kerala, some parts of 40C over isolated pockets of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam Tamil Nadu. and Tamil Nadu. Mean maximum temperature was between 28 to 320C It was normal to near normal over rest of the country over Konkan & Goa, Karnataka, Telangana, Coastal except many parts of Punjab, Haryana & Delhi, West Andhra Pradesh, Rayalaseema, many parts of Madhya Rajasthan, West Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat region, some Maharashtra, Marathwada, Tamil Nadu, Andaman & parts of East Rajasthan, East Madhya Pradesh, Gangetic Nicobar Islands, some parts of Vidarbha, Odisha, West Bengal and isolated pockets of Uttar Pradesh, Kerala and isolated pockets of Gujarat region, Saurashtra, Madhya Maharashtra, Vidarbha, where it was Chhattisgarh and Lakshadweep. below normal by 2 to 40C. Mean maximum temperature was between 20 to 280C over rest of the Country except Jammu & Kashmir, Himachal Pradesh, Punjab, Haryana & Delhi, many parts of Uttarakhand, some parts of West Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan, where it was between 16 to 200C .