Bridging Research and Practice a Handbook for Implementing Research-Informed Practices in Juvenile Probation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

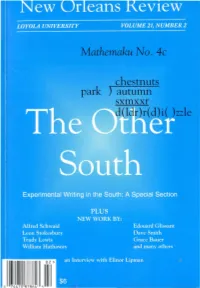

Mathemaku No. 4C

Mathemaku No. 4c chestnuts park ) autumn zzle 0 2 > o 74470 R78fl4 ~ New Orleans Review Summer 1995 Volume 21, Number 2 Editor Associate Editors Ralph Adamo Sophia Stone Cover: poem, "Mathemaku 4c," by Bob Grumman. Michelle Fredette Art Editor Douglas MacCash New Orleans Review is published quarterly by Loyola University, New Orleans, Louisiana 70118, United States. Copyright© 1995 by Loyola Book Review Editor Copy Editor University. Mary A. McCay T.R. Mooney New Orleans Review accepts submissions of poetry, short fiction, essays, and black and white art work or photography. Translations are also welcome but must be accompanied by the work in its original language. All submis Typographer sions must be accompanied by a self-addressed stamped envelope. Al John T. Phan though reasonable care is taken, NOR assumes no responsibility for the loss of unsolicited material. Send submissions to: New Orleans Review, Box 195, Loyola University, New Orleans, Louisiana 70118. Advisory/Contributing Editors John Biguenet Subscription rates: Individuals: $}8.00 Bruce Henricksen Institutions: $21.00 William Lavender Foreign: $32.00 Peggy McCormack Back Issues: $9.00 apiece Marcus Smith Contents listed in the PMLA Bibliography and the Index of American Periodical Verse. Founding Editor US ISSN 0028-6400 Miller Williams New Orleans Review is distributed by: Ingram Periodicals-1226 Heil Quaker Blvd., LaVergne, TN 37086-7000 •1-800-627-6247 DeBoer-113 East Centre St., Nutley, NJ 07110 •1-201-667-9300 Thanks to Julia McSherry, Maria Marcello, Lisa Rose, Mary Degnan, and Susan Barker Adamo. Loyola University is a charter member of the Association of Jesuit University Presses (AJUP). -

To See Volume 1 Preview

The Great American Poetry Show The Great American Poetry Show Volume 1 edited by Larry Ziman Madeline Sharples Nicky Selditz The Muse Media West Hollywood The Great American Poetry Show Published by The Muse Media Post Office Box 69506 West Hollywood, California 90069 323-969-4905 Volume One: Copyright © 2004 by Larry Ziman Cover Design: Copyright © 2004 by Larry Ziman All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any form whatsoever without prior written permission from the publisher except in short quotations appearing in critical articles and reviews. Library of Congress Control Number: 2004114296 ISBN 0-933456-05-0 ISSN 1550-0527 Printed by Thomson-Shore, Inc. 7300 West Joy Road Dexter, Michigan 48130-9701 Text set in Plantin and printed on acid-free paper First printing: 1000 copies, October 2004 Manufactured in the United States of America For information about discounts for classroom and other special orders, please contact: Special Orders, The Muse Media, Post Office Box 69506, West Hollywood, California 90069. The Great American Poetry Show is a serial poetry anthology open year-round to submissions of poems in any subject, style and number with a SASE (self-addressed stamped envelope). Submissions without a SASE will be discarded. No e-mail submissions. Simultaneous submissions and previously published poems are welcome. www.thegreatamericanpoetryshow.com Submit poems to: The Great American Poetry Show, Post Office Box 69506, West Hollywood, California 90069. The Great American Poetry Show Susan Ahdoot Mutiny in the Body . 1 Ronald Douglas Bascombe Superstar, How Do You Play My Song? . 2 Grace Bauer Café Culture #1 . -

Hiram Poetry Review Issue #82 Spring 2021 2 the Hiram Poetry Review

Hiram Poetry Review Issue #82 Spring 2021 2 The Hiram Poetry Review 3 THE HIRAM POETRY REVIEW ISSN 0018-2036 Indexed in American Humanities Index Submission Guidelines: 3-5 poems, SASE. HPR, P.O. Box 162, Hiram, Ohio 44234 [email protected] hirampoetryreview.wordpress.com $9.00 for one year or $23.00 for three years 4 THE HIRAM POETRY REVIEW Issue No. 82 Spring 2021 Editor: Willard Greenwood Associate Editor: Mary Quade Editorial Assistants: Kerry Hamilton, Lauren Hildum, and Quinn Tucker Cover Photo by: Lauren Hildum CONTENTS Editor’s Note 8 David Adams 23-South 9 Anthony Aguero Effigy of my Drug Dealer 11 Fred Arroyo Old Manuel 12 Zulfa Arshad Mango Peels 13 Just a Moment 14 Enne Baker Cystoscopy 15 Grace Bauer Ms. Schadenfreude on Pestilence 16 Demetrius Buckley Coming Back Tonight 17 Jim Daniels TESTAMENT 19 Edmund Dempsey Middle of the Road 21 Norah Esty Fishing, Thirty Years Later 22 Five Bottles of Champagne 24 5 Jess Falkenhagen Never Again 25 Antony Fangary dear u.s. 26 Dan Grote The Creative Process 27 Anvesh Jain Bagah Border, at Age 11 28 Charles Kell Saxifraga 30 Robert McCracken Untitled 33 R. McSwain Normal 34 Mycah Miller Honeycomb Queer 35 Cecil Morris Saying Goodbye 36 Daniel Morris Another Virus 37 James Nnaji Black Crude Poured Again 40 David Sapp Aristocracy 42 John Saad Honeymoon, Dodger Stadium 43 Denzel Scott Garland of Delphinium 44 Bonnie Stanard Conditioned to Impress 45 6 Pamela Sumners The Caretakers 47 Review Charles Parsons Standing Downstream: a review of Everything Comes Next (Greenwillow Books) by Naomi Shihab Nye 49 Contributors’ Notes 52 7 EDITOR’S NOTE Welcome to our second pandemic issue. -

Annual Report 2018

2018 ANNUAL REPORT ART & EDUCATION W. Russell G. Byers Jr. BOARD OF TRUSTEES COMMITTEE Buffy Cafritz (as of September 30, 2018) Frederick W. Beinecke Calvin Cafritz Chairman Leo A. Daly III Earl A. Powell III Gregory W. Fazakerley Mitchell P. Rales Juliet C. Folger Sharon P. Rockefeller Marina Kellen French David M. Rubenstein Norma Lee Funger Andrew M. Saul Whitney Ganz Sarah M. Gewirz FINANCE COMMITTEE Lenore Greenberg Mitchell P. Rales Andrew S. Gundlach Chairman Jane M. Hamilton Steven T. Mnuchin Secretary of the Treasury Richard C. Hedreen Teresa Heinz Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Frederick W. Beinecke Sharon P. Rockefeller Helen Lee Henderson Chairman President David M. Rubenstein Betsy K. Karel Andrew M. Saul Kasper Linda H. Kaufman Kyle J. Krause AUDIT COMMITTEE David W. Laughlin Andrew M. Saul Chairman Reid V. MacDonald Frederick W. Beinecke Nancy Marks Mitchell P. Rales Jacqueline B. Mars Sharon P. Rockefeller Constance J. Milstein David M. Rubenstein Scott Nathan Mitchell P. Rales David M. Rubenstein John G. Pappajohn Sally Engelhard Pingree TRUSTEES EMERITI William A. Prezant Julian Ganz, Jr. Diana C. Prince Alexander M. Laughlin Hilary Geary Ross David O. Maxwell Roger W. Sant Victoria P. Sant † Thomas A. Saunders III John Wilmerding Fern M. Schad Leonard L. Silverstein † EXECUTIVE OFFICERS Albert H. Small Frederick W. Beinecke Michelle Smith President Andrew M. Saul John G. Roberts Jr. Benjamin F. Stapleton III Chief Justice of the Earl A. Powell III United States Director Stephen G. Stein Franklin Kelly Luther M. Stovall Deputy Director and Alexa Davidson Suskin Chief Curator Diana Walker Darrell R. -

September 2008 Caa News Contents

NEWSLETTER OF THE COLLEGE ART ASSOCIATION VOLUME 33 NUMBER 5 SEPTEMBER 2008 CAA NEWS CONTENTS FEATURES 1 From the Executive Director 2 caa.reviews at Ten Years 5 Contemporary Art Galleries in Downtown Los Angeles 7 New Directories of Graduate Programs in the Arts CURRENTS 8 Upcoming Workshops for Artists 8 Exhibit Your Art in Los Angeles 8 Linda Downs at the Rachofsky Mentors Needed for Conference House in Dallas during the 2008 9 Los Angeles Conference Annual Conference (photograph by Registration Teresa Rafidi) 10 Participate in Conference Mentoring FROM THE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR 10 Conference Travel Grants 11 Projectionist and Room Monitors As the new academic year begins, various CAA committees and staff members are finish- Needed ing preparations for the Annual Conference in Los Angeles in February 2009. In the ten years since CAA was last there, LA has experienced tremendous growth in the visual 11 Conference Curatorial Proposals arts, especially with its diverse art-school and university programs; new and expanded art 12 Publications museums; booming art galleries in many neighborhoods; and a revived, lively downtown. 12 Intellectual Property and the Arts The conference program is rich and varied, and special events will occur all over the city. I 15 CAA News urge all members to take advantage of this year’s conference by registering early—starting 15 Affiliated Society News online in October. On July 24, CAA organized a daylong editorial workshop with experts in the legal and publishing fields for members of the Board of Directors, journal editors, Publications END NOTES Committee members, and CAA staff to explore the risks of publishing journals internationally 18 Solo Exhibitions by Artist and to review editorial procedures and policies. -

Solutions to the Crisis in Juvenile Justice

FAMILIES UNLOCKING FUTURES: SOLUTIONS TO THE CRISIS IN JUVENILE JUSTICE A REPORT BY JUSTICE FOR FAMILIES WITH RESEARCH SUPPORT BY DATACENTER SEPTEMBER 2012 1 RESEARCH TEAM This report was a collaborative effort by several grassroots organizations and two resource organizations, which provided research, policy, and writing support for this project. All par- ticipating grassroots organizations are members of Justice for Families, a national alliance of membership-based organizations and allies organizing to build a united response to the crisis in juvenile justice across the country. RESOURCE ORGANIZATIONS Justice for Families Zachary Norris and Grace Bauer, Co-Directors Justice for Families (J4F) is a national alliance of local organiza- tions working to transform families from victims of the prison epidemic to leaders of the movement for fairness and opportunity for all youth. We are founded and run by parents and families who have experienced “the system” directly with their own children (often the survivors of crime themselves), and who are taking the lead to help build a family-driven and trauma-informed youth justice system. J4F is building a national bipartisan movement for justice reinvestment—the reallocation of government resources away from mass incarceration and toward investment in families and communities. DataCenter Christine Schweidler and Saba Waheed DataCenter is a national, independent research organization for social justice movements and grassroots organizing. Rooted in progressive social movements and grounded in values of justice and self-determination for communities, DataCenter believes in advancing the concept and strategy of Research Justice—a theory and practice for social change that validates all forms of knowledge, and puts information in the hands of communities organizing for justice. -

Trump to Take

Questions? Call 1-800-Tribune Thursday, February 14, 2019 Breaking news at chicagotribune.com Harvest Trump Bible to take Chapel pastor out ‘serious MacDonald fired for conduct ‘harmful to’ look’ Chicago-area church By Patrick M. O’Connell President plays coy and Morgan Greene on border deal — but Chicago Tribune still claims victory James MacDonald, the sen- By Jill Colvin, Alan Fram ior pastor and founding mem- and Catherine Lucey ber of Harvest Bible Chapel, Associated Press has been fired, the church announced early Wednesday WASHINGTON — Even be- morning. The announcement fore seeing a final deal or comes nearly one month after agreeing to sign it, President church elders said MacDonald, Donald Trump labored on a popular preacher who at- Wednesday to frame the con- tracted thousands of gressional agreement on bor- worshippers to his network of der security as a political win, churches in Chicago and the never mind that it contains only suburbs each weekend, was a fraction of the billions for a taking an “indefinite sabbati- “great, powerful wall” that he’s cal.” been demanding for months. A statement by church Trump is expected to grudg- elders cited “conduct that the ABEL URIBE/CHICAGO TRIBUNE ingly accept the agreement, Elders believe is contrary and Grace Bauer and her grandfather attend Wednesday’s memorial for her father in Chicago. which would avert another harmful to the best interests of government shutdown and the church” as the reason for give him what Republicans MacDonald’s immediate ter- have been describing as a mination, effective Tuesday. “down payment” on his signa- The decision to remove ture campaign pledge.