Jaffna College MISCELLANY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Test of Character for Jaffna Rivals for Sissies Was Perturbed Over a Comment St

Thursday 25th February, 2010 15 93rd Battle of the Golds Letter Shopping is A test of character for Jaffna rivals for Sissies was perturbed over a comment St. Patrick’s College Jaffna College made by Mr. Trevor Chesterfield in Ihis regular column in your esteemed newspaper on 22.02.2010. Writing about terrorism and its effect on sports he retraces the history particularly cricket, in the recent past. Then he directly refers to events that led to the boycott of World Cup match- es in Sri Lanka by Australia and West Indies. This is what he wrote: “Now Shane Warne is thinking about his options. He did the same in 1996 during the World Cup when both Australia and West Indies declined to Seated from left: A. M. Monoj, M. D. Sajeenthiran, S. Sahayaraj (PoG), P. Seated from left: M. Thileepan (Asst. Coach), S. Komalatharan, S. Niroshan, S. play their games in Colombo after the Navatheepan (Captain), Rev. Fr. Gero Selvanayaham (Rector), S. Milando Jenifer (V. Seeralan (V. Capt), B. L. Mohanakumar (Physical Director), N. A. Wimalendran truck bomb at the Central Bank. Capt), P. Jeyakumar (MiC), A. S. Nishanthan (Coach), B. Michael Robert, M. V. (Principal), P. Srikugan (Captain), J. Nigethan, B. Prasad, R. Kugan (Coach). Typically,politicians opened their jaws Hamilton. Standing from left: Marino Sanjay, G. Tishanth Tuder, J. Livington, V. Standing from left: S. Vishnujan, P. Sobinathsuvan, R. Bentilkaran, K. Trasopanan, and one crassly suggested how in ref- Kuhabala, A. M. Nobert, G. Morison, Erik Prathap, V. Jehan Regilus, R. Ajith Darwin, T. Priyalakshan, N. Bengamin Nirushan, S. -

Justice Denied: a Reality Check on Resettlement, Demilitarization, And

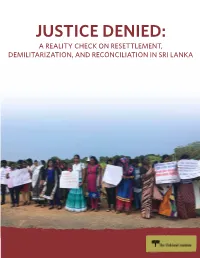

JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA Acknowledgements This report was written by Elizabeth Fraser with Frédéric Mousseau and Anuradha Mittal. The views and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of The Oakland Institute alone and do not reflect opinions of the individuals and organizations that have sponsored and supported the work. Cover photo: Inter-Faith Women’s Group in solidarity protest with Pilavu residents, February 2017 © Tamil Guardian Design: Amymade Graphic Design Publisher: The Oakland Institute is an independent policy think tank bringing fresh ideas and bold action to the most pressing social, economic, and environmental issues. Copyright © 2017 by The Oakland Institute. This text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The copyright holder requests that all such uses be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, reuse in other publications, or translation or adaptation, permission must be secured. For more information: The Oakland Institute PO Box 18978 Oakland, CA 94619 USA www.oaklandinstitute.org [email protected] Acronyms CID Criminal Investigation Department CPA Centre for Policy Alternatives CTA Counter Terrorism Act CTF Consultation Task Force on Reconciliation Mechanisms IDP Internally Displaced Person ITJP International Truth and Justice Project LTTE Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam OMP Office on Missing Persons PTA Prevention of Terrorism Act UNCAT United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment UNHRC United Nations Human Rights Council 3 www.oaklandinstitute.org Executive Summary In January 2015, Sri Lanka elected a new President. -

Alumni Message from Principal Solomon in THIS NEWSLETTER

Rev. Dr. Davidsathananthan Solomon, Principal Jaffna College [email protected] Volume 1, Issue 1, 2017 IN THIS NEWSLETTER Chairperson Jaffna College Board Alumni Message from Principal Solomon Editor’s Greetings College Students Perform Well in Examinations Upgrade to Daniel Poor Library New Junior Vice Principal English Language Resources A Generous Gift for Physical Education Starting an English Laboratory WELCOME TO “STEPPING UP’ FROM THE CHAIR OF THE BOARD On behalf of the Jaffna College Board of Directors, welcome to this first E-newsletter for our College Alumni, Stepping Up. I congratulate Principal Solomon and Junior Vice-Principal Gladys Muthurajah for their initiative in starting Stepping Up. Their initiative has stepped up to the Board’s challenge to implement a new policy of stakeholder engagement with our Alumni. The Board has recently carried out an extensive review of our governance performance. Following best practice advice specifically for governance development in low-income nations like Sri Lanka, we have adopted a policy to improve our relationships with stakeholders. The Board is committed to work together with Alumni for the benefit of Jaffna College students and staff. I second the Principal’s invitation to you to visit the College. I am continually delighted when Alumni visit me to discuss the College’s development, how they might contribute, and express their interest in better understanding the Board’s role and responsibilities. The Board is committed to better informing you of our work, and looks forward to receiving your feedback. Board minutes are available to you in the Principal’s office, for your information. As a Board, we have been stepping up to meet the challenges facing us. -

Jaffna College Miscellany

YALE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY 3 9002 09912 4050 JAFFNA COLLEGE MISCELLANY AUGUST, 1030. Jaffna College Miscellany August, 1939. VOL. XLIX. No. 2. JAFFNA COLLEGE MISCELLANY M a n a g e r : K. Sellaiah E d it o r s : S. H. Perinbanayagam L. S. Kulathungam The Jaffna College Miscellany is published three times a year, at the close of each term of the College year. The rate of annual subscription is Rs. 2.00 including postage. Advertisement rates are sent on application. Address all business communications and remit all subscriptions to:— The Manager, Jaffna College Miscellany, Vaddukoddai, Ceylon. American Ceyioir Mission Press, Tellippalai. CONTENTS Page Origin of the Tamil Language - 1 A note on Modern English Poetry - 11 Some more popular fallacies 17 (g>) - - 23 Y. M. C. A. - - 26 The Academy - - 27 House Reports Abraham House - 28 Brown House - - 30 Hastings House - - 31 Hitchcock House - - 34 The Hunt Dormitory Union 36 The Athenaeum - - 36 The Scout Troop - 37 The All-Ceylon Boy Scout Jamboree - 39 Physical Director’s Notes - 43 Annual Field Day Sports Meet 1939 - 49 Principal’s Notes - - 56 The Jaffna College Alumni Association News and Notices - 59 The Jaffna College Alumni Association Alumni Day - 65 The Jaffna College Alumni Association Treasurer’s Announcement - - 77 Alumni Notes - - 78 Editorial Notes - - 82 Matriculation Results - 91 Notes from a College Diary - 92 The Miscellany File 102 Our Exchange List - - 103 ORIGIN OF THE TAMIL LANGUAGE (B y R e v . S. G n a n a P r a k a s a r , o . m . i .) Tamil ever Ancient and New Tamil is said to be the most ancient of the languages now spoken in the world. -

Open Competitive Examination for the Post of Office

OPEN COMPETITIVE EXAMINATION FOR THE POST OF OFFICE EMPLOYEES SERVICE GRADE III IN THE NORTHERN PROVINCE – 2015 EXAM HELD ON :06.02.2016 RESULTS District: Jaffna Sr.N Index No Full Name Address Ethnic Medium NIC No IQ & GK LP Total 1 800111 Mathan Vanathy Pilavady Road, Puloly South, Puloly SriLanka Tamil Tamil 885433928V 64 96 160 2 100168 Kanthasamy Thinesh Neervely North, Pannalai SriLanka Tamil Tamil 951351407V 71 88 159 1st Lane, Karanthan Road, 3 101382 Selvarajah Suvarsana SriLanka Tamil Tamil 936962564V 74 85 159 Urumpirai East, Urumpirai Mary Kalista Rose Thiresh 4 700052 Vettilaikkerny, Mulliyan SriLanka Tamil Tamil 896043293V 72 87 159 Pushpam Rajasingam Lane, Valvetti, 5 101861 Thurainayagam Jayanthan SriLanka Tamil Tamil 912632571V 72 86 158 Valvettithurai. Sivapilavathai, Alvai North Centre, 6 300696 Selvarasa Sabeshkumar SriLanka Tamil Tamil 761793772V 73 85 158 Alvai Miththilkarai, Thunnalai West, 7 800624 Valarmathy Kathiravelu SriLanka Tamil Tamil 915730973V 66 91 157 Karaveddy. 30, Poothavarajar Road, Tirunelvely 8 102701 Rasanayagam Senkodan SriLanka Tamil Tamil 941732356V 68 85 153 East. 9 101902 Thamayanthy Nagulesvaran 28/3, Hospital Road, Jaffna. SriLanka Tamil Tamil 927011506V 68 84 152 "College of Informatics Studies" 10 102604 Sitsabesan Gowreeshan SriLanka Tamil Tamil 892251193V 68 84 152 K.K.S Road, Inuvil West, Inuvil 11 700068 Allvan Anantharajah Navatkadu, Varany SriLanka Tamil Tamil 730974620V 68 84 152 12 102338 Santhiran Shabeshan Vasavilan South, Thidatpulam SriLanka Tamil Tamil 820514670V 66 85 151 Page 1 of 327 OPEN COMPETITIVE EXAMINATION FOR THE POST OF OFFICE EMPLOYEES SERVICE GRADE III IN THE NORTHERN PROVINCE – 2015 EXAM HELD ON :06.02.2016 RESULTS District: Jaffna Sr.N Index No Full Name Address Ethnic Medium NIC No IQ & GK LP Total 473/1, Arasolai, Neervely North, 13 100969 Sachchithanantham Sudhagaran SriLanka Tamil Tamil 800994012V 67 83 150 Neervely. -

Joint Humanitarian Update NORTH EAST | SRI LANKA

Joint Humanitarian Update NORTH EAST | SRI LANKA JAFFNA, KILINOCHCHI, MULLAITIVU, MANNAR, VAVUNIYA and TRINCOMALEE DISTRICTS Report # 9 | 12 September – 25 September 2009 Displacement after April 2008 - IDP situation as reported by Government Agents as of 28 September 2009 IDPs 255,551 persons are currently accommodated in camps and During the period 1 April 2008 hospitals. to 28 September 2009 Vavuniya Camps: 238,0561 Mannar Camps: 1,3992 253,567 people are accommodated in temporary camps. Jaffna Camps: 7,3783 Trincomalee Camps: 6,7344 1,9845 IDPs (injured and care givers) are in hospitals in various Hospitals: districts6 as of 28 August 2009. RELEASES, RETURNS & TRANSFERS 7,835 people have been released from temporary camps into Releases: host families and elders’ homes as of 24 September 2009. The majority of these people are elders, people with learning disabilities and other vulnerable groups. Returns to places of origin: 6,813 have been returned to Jaffna, Vavuniya, Mannar, Trincomalee, Batticaloa and Ampara districts between 5 August and 28 September 2009. Transfers to the districts of origin and 3,358 have been transferred to Jaffna, Trincomalee, Batticaloa accommodated in transit sites: and Ampara districts between 11 September and 28 September 2009. 1 Source: Government Agent Vavuniya 2 Source: Government Agent Mannar 3 Source: Government Agent Jaffna 4 Source: Government Agent Trincomalee 5 Source: Ministry of Health 6 This includes GH Vavuniya, BH Cheddikulam, BH Poovarasankulum, Pampainmadu Hospital, DGH Mannar, BH Padaviya, GH Polonnaruwa, TH Kurunagala 1 Joint Humanitarian Update NORTH EAST | SRI LANKA I. Situation Overview & highlights • On 14 September, the Minister of Disaster Management and Human Rights Mahinda Samarasinghe rejected claims made by the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights, Navanethem Pillai, that the displaced people in Sri Lanka are being kept in internment camps, as opposed to what the Government of Sri Lanka (GoSL) defines as welfare villages. -

Jaffna District – 2007

BASIC POPULATION INFORMATION ON JAFFNA DISTRICT – 2007 Preliminary Report Based on Special Enumeration – 2007 Department of Census and Statistics June 2008 Foreword The Department of Census and Statistics (DCS), carried out a special enumeration in Eastern province and in Jaffna district in Northern province. The objective of this enumeration is to provide the necessary basic information needed to formulate development programmes and relief activities for the people. This preliminary publication for Jaffna district has been compiled from the reports obtained from the District based on summaries prepared by enumerators and supervisors. A final detailed publication will be disseminated after the computer processing of questionnaires. This preliminary release gives some basic information for Jaffna district, such as population by divisional secretary’s division, urban/rural population, sex, age (under 18 years and 18 years and over) and ethnicity. Data on displaced persons due to conflict or tsunami are also included. Some important information which is useful for regional level planning purposes are given by Grama Niladhari Divisions. This enumeration is based on the usual residents of households in the district. These figures should be regarded as provisional. I wish to express my sincere thanks to the staff of the department and all other government officials and others who worked with dedication and diligence for the successful completion of the enumeration. I am also grateful to the general public for extending their fullest co‐operation in this important undertaking. This publication has been prepared by Population Census Division of this Department. D.B.P. Suranjana Vidyaratne Director General of Census and Statistics 6th June 2008 Department of Census and Statistics, 15/12, Maitland Crescent, Colombo 7. -

Jaffna College Miscellany

JAFFNA COLLEGE MISCELLANY DECEMBER, 1938. % lïtfrrir (Æ jm sim ;« anìr JV jJCajjjiy Jípíu TQtat Jaffna College Miscellany December, 1938- v o l . XLVIII. No. 3. JAFFNA COLLEGE MISCELLANY M a n a g e r : K. Sellaiah. E d i t o r s : S. H. Perinbanayagam. L. S. Kulathungam. The Jaffna College Miscellany is published three times a year, at the close of each term of the College year. The rate of annual subscription is Rs. 2 00 including postage. Advertisement rates are sent on application. Address all business communications and remit all subscriptions to:— The Manager, Jaffna College Miscellany. Vaddukoddai, Ceylon. American Ceylon Mission Press. Tellippalai. CONTENTS P a g e Editorial Notes - 1 My Post-University Course at Jaffna College - 10 A Modern American Theologian 21 ULpWAHjm - So Some Ancient Tamil Poems - 43 Principal’s Notes - 51 Our Results - 56 Parent—Teachers’ Association - 57 The Student Council - 58 The Inter Union -, - 59 “Brotherhood” - 62 Lyceum - 64 Hunt Dormitory Union - 63 The Athenaeum - 68 Scout Notes - 70 Sports Section-Report of the Physical Department— 1938 72 Hastings House - 75 Abraham House - 76 Hitchcock House - 80 Brown House 81 Sports ¡S3 List of Crest Winners 85 Annual Report of the Y. M. C. A. - 87 Jaffna College Alumni Association (News & Notes) 94 Jaffna College Alumni Association (Alumni Day) 97 Treasurer’s Announcement 107 Jaffna College Alumni Association (Statement of Accounts) 108 Jaffna College Alumni Association (List of Members Contribut ions) 109 Principal’s Tea to the Colombo Old Boys - 111 The Silver Jubilee Meeting of the Colombo Old Boys 113 The Silver Jubilee Dinner 117 Old boys News - 123 Notes from the College Diary - 127 The Silver Jubilee Souvenir - 136 Wanted - 140 Silver Jubilee Souvenir of the Old Boys' Association 140 Old Boys’ Register . -

American Ceylon Mission

, RE:p~·a·R T , "", .I.:.~ OF THE '.(. .~, ... AMERICAN CEYLON MISSION . .. "', FOR 1852. PUBLISHED Xli 1849. I;:,: . » •. "":. .~. REPORT OF THE A~IERICAN CEYLON MISSION, FOR THE YEAR 1852. 3}affna: AMERICAN MISSION PRESS-To S. BURNELL, PRINTER. Hl53. REPORT ALTHOUGH we have not been in the habit of publishing an annual report of our labors, we find an occasional review of the way in which the Lord has led us, profitable to ourselves and encouraging to those who feel an interest in the establishment of Christ's kingdom in this land. As it is now several years since such a review was taken, the following report of the operations of the past year, will contain a more extended statement of the state and progress of the work than would otherwise be necessary. Missionaries and Stations. Though we have been favored by the accession of Mr. and Mrs. Sanders to our number during the year,. yet the absence of others on account of ill-health has prevented the occupancy of vacant stations. Chavagacherry has been vacant during a part of the year by tke absence of Mr. and Mrs. Noyes on a visit to the continent. As the clima te in that region seems more favorable to the health of Mrs. Noyes, they now contemplate a permanent removal to the Madura Mission. Mr. and Mrs. Mills left for Madras in August, on account of her feeble health, expecting to be obliged to proceed to Amer ica. After a reside~ce of several months in Madras, they have been enabled to return to us, and resume their duties in con nection with the Seminary, and Mr. -

Slavery and Caste Supremacy in the American Ceylon Mission

Article CASTE: A Global Journal on Social Exclusion Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 155–174 February 2020 brandeis.edu/j-caste ISSN 2639-4928 DOI: 10.26812/caste.v1i1.117 In Nāki’s Wake: Slavery and Caste Supremacy in the American Ceylon Mission Mark E. Balmforth1 (Bluestone Rising Scholar Honorable Mention 2019) Abstract In 1832, a woman named Caṅkari Nāki died in Ceylon, and her descendants have been haunted by a curse ever since. One of the first converts of the American Ceylon Mission, Nāki was part of an enslaved caste community unique to the island, and one of the few oppressed-caste members of the mission. The circumstances of her death are unclear; the missionary archive is silent on an event that one can presume would have affected the small Christian community, while the family narrative passed through generations is that Nāki was murdered by members of the locally dominant Vellalar caste after marrying one of their own. In response to this archival erasure, this essay draws on historical methods developed by Saidiya Hartman and Gaiutra Bahadur to be accountable to enslaved and indentured lives and, in Hartman’s words, to ‘make visible the production of disposable lives.’ These methods actively question what we can know from the archives of an oppressor and, for this essay, enable a reading of Nāki’s life at the centre of a mission struggling over how to approach caste. Nāki’s story, I argue, helps reveal an underexplored aspect of the interrelationship between caste and slavery in South Asia, and underlines the value of considering South Asian slave narratives as source material into historiographically- and archivally-obscured aspects of dominant caste identity. -

The CONSTITUTION of the Board of Directors of Jaffna College

The CONSTITUTION of the Board of Directors of Jaffna College (As approved at the Semi-Annual Meeting of October 10, 2014) ARTICLE I: The Institution shall be called JAFFNA COLLEGE. ARTICLE II: It shall be conducted as a Christian College whose Directors shall be members of a denomination of Protestant Christians with the exception that the alumni of the College may elect one alumnus of the College to the Board without regard to religious affiliation. (Note: In this and in subsequent articles, where the word “Protestant”is used reference is made to Churches which are members of the National Christian Council of Sri Lanka, NCCSL). ARTICLE III: The object of the Institution shall be to give all pupils or students admitted into the College a thorough and holistic general and Christian Education. ARTICLE IV: The Board of Directors The Board of Directors of Jaffna College is an incorporated body by an ordinance enacted by the Governor of Ceylon, with the advice and consent of the Legislative Council thereof No.7 of 1894. ARTICLE V: Powers a) The Government and direction of the College shall be vested in the Board of Directors, not more than fourteen and not less than eleven in number. b) The Board of Directors will assume responsibility for the running of the Christian Institute for the Study of Religion and Society. The making of a Constitution for this Institute shall be the responsibility of the Board. All assets of the Institute, movable and immovable, shall vest in the Board of Directors of Jaffna College. 1 c) The Board of Directors shall make a Constitution for the Jaffna College Institute of Technology (JCIT) and Jaffna College Institute of Agriculture (JCIA). -

St. John's Began with Just Seven Students by Professor S

St. John's Began with just seven students By Professor S. Ratnajeevan H. Hoole (Extracted from The Sunday Leader, April 5, 1998) This year St. John's celebrates its 175th anniversary. The dynamic enterprise that is St. John's must be judged in light of the motivation and dedication of its founders, who were determined to serve selflessly what must surely have been a strange people in a strange land. The early years of the 19th century saw the expansion of Christian missions in the British colonies. Colonial administrative officials, with their eye on profit, wanted good relations with the locals and had forbidden any Christian evangelical work and refused to employ those locals who had taken up the Christian faith. In the first year of British rule alone, 300 new Hindu temples were built in Jaffna by the British. Indeed, the antagonism to Christianity in the 20 year lull between the British take-over and the arrival of the first missionaries saw the number of temples in Jaffna growing 4 fold. The growing evangelical movement in England's Parliament put a stop to this and since 1813 Christian missions started to spread throughout the colonies. Arrival of Rev. Knight This development brought to Sri Lanka the Rev. Joseph Knight (born in Stroud, England, on October 17, 1787) and three others who were given the requisite training and ordained priest just before their departure in the Autumn of 1817 as missionaries of the Church Missionary Society, the CMS. It was a dangerous journey to the East with many a missionary dying or losing a family member before the journey's end.