Classical Source LP Feature August 2917

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Season 125, 2005-2006

Tap, tap, tap. The final movement is about to begin. In the heart of This unique and this eight-acre gated final phase is priced community, at the from $1,625 million pinnacle of Fisher Hill, to $6.6 million. the original Manor will be trans- For an appointment to view formed into five estate-sized luxury this grand finale, please call condominiums ranging from 2,052 Hammond GMAC Real Estate to a lavish 6,650 square feet of at 617-731-4644, ext. 410. old world charm with today's ultra-modern comforts. BSRicJMBi EM ;\{? - S'S The path to recovery... a -McLean Hospital ', j Vt- ^Ttie nation's top psychiatric hospital. 1 V US NeWS & °r/d Re >0rt N£ * SE^ " W f see «*££% llffltlltl #•&'"$**, «B. N^P*^* The Pavijiorfat McLean Hospital Unparalleled psychiatric evaluation and treatment Unsurpassed discretion and service BeJmont, Massachusetts 6 1 7/855-3535 www.mclean.harvard.edu/pav/ McLean is the largest psychiatric clinical care, teaching and research affiliate R\RTNERSm of Harvard Medical School, an affiliate of Massachusetts General Hospital HEALTHCARE and a member of Partners HealthCare. REASON #78 bump-bump bump-bump bump-bump There are lots of reasons to choose Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center for your major medical care. Like less invasive and more permanent cardiac arrhythmia treatments. And other innovative ways we're tending to matters of the heart in our renowned catheterization lab, cardiac MRI and peripheral vascular diseases units, and unique diabetes partnership with Joslin Clinic. From cardiology and oncology to sports medicine and gastroenterology, you'll always find care you can count on at BIDMC. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs

m fl ^ j- ? i 1 9 if /i THE GREAT OUTDOORS THE GREAT INDOORS Beautiful, spacious country condominiums on 55 magnificent acres with lake, swimming pool and tennis courts, minutes from Tanglewood and the charms of Lenox and Stockbridge. FOR INFORMATION CONTACT (413) 443-3330 1136 Barker Road (on the Pittsfield-Richmond line) GREAT LIVING IN THE BERKSHIRES Seiji Ozawa, Music Director Carl St. Clair and Pascal Verrot, Assistant Conductors One Hundred and Seventh Season, 1987-88 Trustees of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. Kidder, President Nelson J. Darling, Jr., Chairman George H. T Mrs. John M. Bradley, Vice-Chairman J. P. Barger, V ice-Chairman Archie C. Epps, Vice-Chairman William J. Poorvu, Vice-Chairman and Treasurer Vernon R. Alden Mrs. Michael H. Davis Roderick M. MacDougall David B. Arnold, Jr. Mrs. Eugene B. Doggett Mrs. August R. Meyer Mrs. Norman L. Cahners Mrs. John H. Fitzpatrick David G. Mugar James F. Cleary Avram J. Goldberg Mrs. George R. Rowland William M. Crozier, Jr. Mrs. John L. Grandin Richard A. Smith Mrs. Lewis S. Dabney Francis W. Hatch, Jr. Ray Stata Harvey Chet Krentzman Trustees Emeriti Philip K. Allen Mrs. Harris Fahnestock Irving W. Rabb Allen G. Barry E. Morton Jennings, Jr. Paul C. Reardon Leo L. Beranek Edward M. Kennedy Mrs. George L. Sargent Richard P. Chapman Albert L. Nickerson Sidney Stoneman Abram T. Collier Thomas D. Perry, Jr. John Hoyt Stookey George H.A. Clowes, Jr. John L. Thorndike Other Officers of the Corporation John Ex Rodgers, Assistant Treasurer Jay B. Wailes, Assistant Treasurer Daniel R. Gustin, Clerk Administration of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Inc. -

Boston Symphony Orchestra Concert Programs, Summer, 1963-1964

TANGLEWOOD Festival of Contemporary American Music August 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 1964 Sponsored by the Berkshire Music Center In Cooperation with the Fromm Music Foundation RCA Victor R£D SEAL festival of Contemporary American Composers DELLO JOIO: Fantasy and Variations/Ravel: Concerto in G Hollander/Boston Symphony Orchestra/Leinsdorf LM/LSC-2667 COPLAND: El Salon Mexico Grofe-. Grand Canyon Suite Boston Pops/ Fiedler LM-1928 COPLAND: Appalachian Spring The Tender Land Boston Symphony Orchestra/ Copland LM/LSC-240i HOVHANESS: BARBER: Mysterious Mountain Vanessa (Complete Opera) Stravinsky: Le Baiser de la Fee (Divertimento) Steber, Gedda, Elias, Mitropoulos, Chicago Symphony/Reiner Met. Opera Orch. and Chorus LM/LSC-2251 LM/LSC-6i38 FOSS: IMPROVISATION CHAMBER ENSEMBLE Studies in Improvisation Includes: Fantasy & Fugue Music for Clarinet, Percussion and Piano Variations on a Theme in Unison Quintet Encore I, II, III LM/LSC-2558 RCA Victor § © The most trusted name in sound BERKSHIRE MUSIC CENTER ERICH Leinsdorf, Director Aaron Copland, Chairman of the Faculty Richard Burgin, Associate Chairman of the Faculty Harry J. Kraut, Administrator FESTIVAL of CONTEMPORARY AMERICAN MUSIC presented in cooperation with THE FROMM MUSIC FOUNDATION Paul Fromm, President Alexander Schneider, Associate Director DEPARTMENT OF COMPOSITION Aaron Copland, Head Gunther Schuller, Acting Head Arthur Berger and Lukas Foss, Guest Teachers Paul Jacobs, Fromm Instructor in Contemporary Music Stanley Silverman and David Walker, Administrative Assistants The Berkshire Music Center is the center for advanced study in music sponsored by the BOSTON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA Erich Leinsdorf, Music Director Thomas D. Perry, Jr., Manager BALDWIN PIANO RCA VICTOR RECORDS — 1 PERSPECTIVES OF NEW MUSIC Participants in this year's Festival are invited to subscribe to the American journal devoted to im- portant issues of contemporary music. -

Columbia Masterworks/Speakers Corner Records – Audiophile Audition 25.05.21, 10�08

Stravinsky Conducts Stravinsky – Columbia Masterworks/Speakers Corner Records – Audiophile Audition 25.05.21, 1008 Classical Reviews Hi-Res Reviews Jazz Reviews Component Reviews Support Audiophile Audition Contact Us More Stereotypes Audio Stravinsky Conducts Stravinsky – Columbia Cembal Masterworks/Speakers Corner d’amour Records Home » SACD & Other Hi-Res Reviews » Stravinsky Conducts Stravinsky – Columbia Masterworks/Speakers Corner Records by Audiophile Audition | May 21, 2021 | Classical Reissue Reviews, SACD & Other Hi-Res Reviews | 0 comments Pure Pleasure / Speakers Corner Stravinsky Conducts Stravinsky – Columbia Masterworks MS 6372 (1962)/Speakers Corner Records (2020) 180-gram stereo vinyl, 45:37 ****: (Igor Stravinsky – composer, conductor; Samuel Barber – piano; Aaron Copland – piano; Lukas Foss – piano; Roger Sessions – piano; Mildred Allen – soprano; Regina Sarfaty – mezzo- Cedille soprano; Loren Driscoll – tenor; George Shirley – tenor; William Murphy – baritone; Donald Graham – bass; Robert Oliver – bass; Toni Koves – cimbalom; featuring the American Concert Choir: Margaret Hillis – director; https://www.audaud.com/stravinsky-conducts-stravinsky-columbia-masterworks-speakers-corner-records/ Seite 1 von 6 Stravinsky Conducts Stravinsky – Columbia Masterworks/Speakers Corner Records – Audiophile Audition 25.05.21, 1008 Columbia Percussion Ensemble; Columbia Chamber Ensemble) The 20th Century era of classical music was notable for its divergent styles. Without a predominant sub-genre, composers engaged in romantic, neo- classicism, modernism, jazz-influenced, impressionism, minimalism and free Site Search dissonance. It is widely believed that the most influential and diverse Search here... composer of this exciting and at times unpredictable time period was Igor Stravinsky. Starting as a student of Rimsky-Korsakov, he redefined rhythmic structures and musical arrangement. His embrace of religious orthodoxy and creative freedom was a unique and potent combination. -

Flamenco Sketches”

Fyffe, Jamie Robert (2017) Kind of Blue and the Signifyin(g) Voice of Miles Davis. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/8066/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten:Theses http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Kind of Blue and the Signifyin(g) Voice of Miles Davis Jamie Robert Fyffe Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Culture and Creative Arts College of Arts University of Glasgow October 2016 Abstract Kind of Blue remains one of the most influential and successful jazz albums ever recorded, yet we know surprisingly few details concerning how it was written and the creative roles played by its participants. Previous studies in the literature emphasise modal and blues content within the album, overlooking the creative principle that underpins Kind of Blue – repetition and variation. Davis composed his album by Signifyin(g), transforming and recombining musical items of interest adopted from recent recordings of the period. This thesis employs an interdisciplinary framework that combines note-based observations with intertextual theory. -

Philharmonic Hall Lincoln Center F O R T H E Performing Arts

PHILHARMONIC HALL LINCOLN CENTER F O R T H E PERFORMING ARTS 1968-1969 MARQUEE The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center is Formed A new PERFORMiNG-arts institution, The Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, will begin its first season of con certs next October with a subscription season of 16 concerts in eight pairs, run ning through early April. The estab lishment of a chamber music society completes the full spectrum of perform ing arts that was fundamental to the original concept of Lincoln Center. The Chamber Music Society of Lin coln Center will have as its home the Center’s new Alice Tully Hall. This intimate hall, though located within the new Juilliard building, will be managed by Lincoln Center as an independent Wadsworth Carmirelli Treger public auditorium, with its own entrance and box office on Broadway between 65th and 66th Streets. The hall, with its 1,100 capacity and paneled basswood walls, has been specifically designed for chamber music and recitals. The initial Board of Directors of the New Chamber Music Society will com prise Miss Alice Tully, Chairman; Frank E. Taplin, President; Edward R. Ward well, Vice-President; David Rockefeller, Jr., Treasurer; Sampson R. Field, Sec retary; Mrs. George A. Carden; Dr. Peter Goldmark; Mrs. William Rosen- wald and Dr. William Schuman. The Chamber Music Society is being organ ized on a non-profit basis and, like other cultural institutions, depends upon voluntary contributions for its existence. Charles Wadsworth has been ap pointed Artistic Director of The Cham ber Music Society of Lincoln Center. The Society is the outgrowth of an in tensive survey of the chamber music field and the New York chamber music audience, conducted by Mr. -

Bruno Walter (Ca

[To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] Erik Ryding and Rebecca Pechefsky Yale University Press New Haven and London Frontispiece: Bruno Walter (ca. ). Courtesy of Österreichisches Theatermuseum. Copyright © by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections and of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Designed by Sonia L. Shannon Set in Bulmer type by The Composing Room of Michigan, Grand Rapids, Mich. Printed in the United States of America by R. R. Donnelley,Harrisonburg, Va. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ryding, Erik S., – Bruno Walter : a world elsewhere / by Erik Ryding and Rebecca Pechefsky. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references, filmography,and indexes. ISBN --- (cloth : alk. paper) . Walter, Bruno, ‒. Conductors (Music)— Biography. I. Pechefsky,Rebecca. II. Title. ML.W R .Ј—dc [B] - A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. For Emily, Mary, and William In memoriam Rachel Kemper and Howard Pechefsky Contents Illustrations follow pages and Preface xi Acknowledgments xv Bruno Schlesinger Berlin, Cologne, Hamburg,– Kapellmeister Walter Breslau, Pressburg, Riga, Berlin,‒ -

Toscanini in Stereo a Report on RCA's "Electronic Reprocessing"

Toscanini in Stereo a report on RCA's "electronic reprocessing" MARCH ERS 60 CENTS FOR STEREO FANS! Three immortal recordings by Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony have been given new tonal beauty and realism by means of a new RCA Victor engineering development, Electronic Stereo characteristics electronically, Reprocessing ( ESR ) . As a result of this technique, which creates stereo the Toscanini masterpieces emerge more moving, more impressive than ever before. With rigid supervision, all the artistic values have been scrupulously preserved. The performances are musically unaffected, but enhanced by the added spaciousness of ESR. Hear these historic Toscanini ESR albums at your dealer's soon. They cost no more than the original Toscanini monaural albums, which are still available. Note: ESR is for stereo phonographs only. A T ACTOR records, on the 33, newest idea in lei RACRO Or AMERICA Ask your dealer about Compact /1 CORPORATION M..00I sun.) . ., VINO .IMCMitmt Menem ILLCr sí1.10 ttitis I,M MT,oMC Mc0001.4 M , mi1MM MCRtmM M nm Simniind MOMSOMMC M Dvoìtk . Rn.psthI SYMPHONY Reemergáy Ravel RRntun. of Rome Plue. of Rome "FROM THE NEW WORLD" Pictures at an Exhibition TOSCANINI ARTURO TOSCANINI Toscanini NBC Symphony Orchestra Arturo It's all Empire -from the remarkable 208 belt- driven 3 -speed turntable -so quiet that only the sound of the music distinguishes between the turntable at rest and the turntable in motion ... to the famed Empire 98 transcription arm, so perfectly balanced that it will track a record with stylus forces well below those recommended by cartridge manufacturers. A. handsome matching walnut base is pro- vided. -

1974 Poncho Auction Prize Program I :'::0 National

-:-.,. ~ .., ~1 ~ - n C!.A .. ~tpOg ., CoO~ < G" .0 ~ 0- """"l-- J: C (\"0. i ,..", 4 " ll"'i c ~ ell C' ... (\0 .. It < it rIA "'~ ~ ~ ~ 0 r- ~ :s I· . ~c1 c:~ ~ ..." "t) III~0 " ~. ! -g -o-g ) .... ".° 0 ..a ( 11.~ ~ 01"1$2 ': ... f} " .. G" Y It! '-0 C3G:lQO ' ', 'JUNE' 19,4- VOLUME 2.' NUMBERS" ., st# GENERAL MANAGER HAL LEE OFFICE ~ANAGER PEGGY HELANDER 1°J.7 SPECIAL PROJECJS ' OAVID MACDONALD OPERATIONS MANAGER CHUCK REINSCH PRODUCTION MANAGER PATCHMAN PROGRAM DIRECTOR BOB FRIEDE MUSIC TOM BERGHAN As of this writing, half way through Memorial KRAB is a non-commercial l' ~~ rted DAVE BENNETT Day weekend, KRAB'S live coverag~ of the.3rd FM radio station in ~Seatt~:,~ ~ In's BOB GWYNNE Annual Northwest Regional Folk-Llfe Fes.tlval goal is to broadcast prot,_ J 01 -., • y RAY SEREBRIN appears to be a complete succe ss. In the ~2 and diversity, music ~hich is elsewheL~ SPOKEN ARTS PAMELA JENNINGS ~ ears ' of its existence, KRAB has never before unperformed, opinions which generate debate, PUBLIC AFFAIRS ANDY GARRISD'N. engaged in a production of this dimension: public events which go unreported, news NEWS 'JE'FF MICHKA technically as elaborate and sophistica~ed, events which may otherwise be suppressed, ENGINEERING GREG BROWN and programatically with such spontaneity and , drama and poetry which, but for KRAB, may NORM AHLQUIST s wch high a quality. By the time Monday night ,. never be heard in Seatt le. PHIL BANNON rolls around we should have brought to you at . You now have before you a KRAB Program Guide. -

Spring/Summer 2002

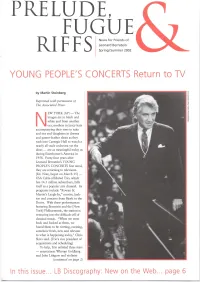

PRELUDE, FUGUE News for Friends of Leonard Bernstein RIFFS Spring/Summer 2002 YOUNG PEOPLE'S CONCERTS Return to TV by Martin Steinberg Reprinted with permission of The Associated Press. EW YORK (AP) - The images are in black and white and from another Nera, mothers in fancy hats accompanying their sons in suits and ties and daughters in dresses and patent-leather shoes as they rush into Carnegie Hall to watch a nearly all-male orchestra yet the ideas ... are as meaningful today as during Eisenhower's America in 1958. Forty-four years after Leonard Bernstein's YOUNG PEOPLE'S CONCERTS first aired, they are returning to television. [Ed. Note, began on March 15] ... USA Cable-affiliated Trio, which has 14.3 million subscribers, bills itself as a popular arts channel. Its programs include "Rowan & Martin's Laugh-In," movies, fash ion and concerts from Bjork to the Doors. With these performances featuring Bernstein and the [New York] Philharmonic, the station is venturing into the difficult sell of classical music. "When we went back and looked at them, we found them to be riveting, exciting, somehow fresh, new and relevant to what is happening today," Chris Slava said. [Trio's vice president of acquisitions and scheduling] To help, Trio enlisted three stars - entertainers Whoopi Goldberg and John Lithgow and violinist (continued on page 2) In this issue ... LB Discography: New on the Web ... page 6 YOUNG PEOPLE'S CONCERTS Return to TV, continued To Our Readers (continued from page 1) sort of put clothes on them so Joshua Bell. They introduce the that they could go out into topic of the day, such as "What is the world. -

The Secularization of the Repertoire of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, 1949-1992

THE SECULARIZATION OF THE REPERTOIRE OF THE MORMON TABERNACLE CHOIR, 1949-1992 Mark David Porcaro A dissertation submitted to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music (Musicology) Chapel Hill 2006 Approved by Advisor: Thomas Warburton Reader: Severine Neff Reader: Philip Vandermeer Reader: Laurie Maffly-Kipp Reader: Jocelyn Neal © 2006 Mark David Porcaro ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MARK PORCARO: The Secularization of the Repertoire of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, 1949-1992 (Under the direction of Thomas Warburton) In 1997 in the New Yorker, Sidney Harris published a cartoon depicting the “Ethel Mormon Tabernacle Choir” singing “There’s NO business like SHOW business...” Besides the obvious play on the names of Ethel Merman and the Mormon Tabernacle Choir, the cartoon, in an odd way, is a true-to-life commentary on the image of the Salt Lake Mormon Tabernacle Choir (MTC) in the mid-1990s; at this time the Choir was seen as an entertainment ensemble, not just a church choir. This leads us to the central question of this dissertation, what changes took place in the latter part of the twentieth century to secularize the repertoire of the primary choir for the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS)? In the 1860s, when the MTC began, its sole purpose was to perform for various church meetings, in particular for General Conference of the LDS church which was held in the Tabernacle at Temple Square in Salt Lake City. From the beginning of the twentieth century and escalating during the late 1950s to the early 1960s, the Choir’s role changed from an in-house choir for the LDS church to a choir that also fulfilled a cultural and entertainment function, not only for the LDS church but also for the American public at large. -

Bulletin 2006/Music/Pages

ale university July 20, 2006 2007 – Number 4 bulletin of y Series 102 School of Music 2006 bulletin of yale university July 20, 2006 School of Music Periodicals postage paid New Haven, Connecticut 06520-8227 ct bulletin of yale university bulletin of yale New Haven Bulletin of Yale University The University is committed to basing judgments concerning the admission, education, and employment of individuals upon their qualifications and abilities and affirmatively seeks to Postmaster: Send address changes to Bulletin of Yale University, attract to its faculty, staff, and student body qualified persons of diverse backgrounds. In PO Box 208227, New Haven ct 06520-8227 accordance with this policy and as delineated by federal and Connecticut law, Yale does not discriminate in admissions, educational programs, or employment against any individual on PO Box 208230, New Haven ct 06520-8230 account of that individual’s sex, race, color, religion, age, disability, status as a special disabled Periodicals postage paid at New Haven, Connecticut veteran, veteran of the Vietnam era, or other covered veteran, or national or ethnic origin; nor does Yale discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation. Issued seventeen times a year: one time a year in May, November, and December; two times University policy is committed to affirmative action under law in employment of women, a year in June; three times a year in July and September; six times a year in August minority group members, individuals with disabilities, special disabled veterans, veterans of the Vietnam era, and other covered veterans. Managing Editor: Linda Koch Lorimer Inquiries concerning these policies may be referred to Valerie O.