Cold War Captives Years Tutoring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biographyelizabethbentley.Pdf

Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet 1 of 284 QUEEN RED SPY Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet 2 of 284 3 of 284 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet RED SPY QUEEN A Biography of ELIZABETH BENTLEY Kathryn S.Olmsted The University of North Carolina Press Chapel Hill and London Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 4 of 284 © 2002 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet The University of North Carolina Press All rights reserved Set in Charter, Champion, and Justlefthand types by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Manufactured in the United States of America The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Olmsted, Kathryn S. Red spy queen : a biography of Elizabeth Bentley / by Kathryn S. Olmsted. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-8078-2739-8 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Bentley, Elizabeth. 2. Women communists—United States—Biography. 3. Communism—United States— 1917– 4. Intelligence service—Soviet Union. 5. Espionage—Soviet Union. 6. Informers—United States—Biography. I. Title. hx84.b384 o45 2002 327.1247073'092—dc21 2002002824 0605040302 54321 Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 5 of 284 To 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet my mother, Joane, and the memory of my father, Alvin Olmsted Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 Tseng 2003.10.24 14:06 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet 6 of 284 7 of 284 Contents Preface ix 6655 Olmsted / RED SPY QUEEN / sheet Acknowledgments xiii Chapter 1. -

Germany: a Global Miracle and a European Challenge

GLOBAL ECONOMY & DEVELOPMENT WORKING PAPER 62 | MAY 2013 Global Economy and Development at BROOKINGS GERMANY: A GLOBAL MIRACLE AND A EUROPEAN CHALLENGE Carlo Bastasin Global Economy and Development at BROOKINGS Carlo Bastasin is a visiting fellow in the Global Economy and Development and Foreign Policy pro- grams at Brookings. A preliminary and shorter version of this study was published in "Italia al Bivio - Riforme o Declino, la lezione dei paesi di successo" by Paolazzi, Sylos-Labini, ed. LUISS University Press. This paper was prepared within the framework of “A Growth Strategy for Europe” research project conducted by the Brookings Global Economy and Development program. Abstract: The excellent performance of the German economy over the past decade has drawn increasing interest across Europe for the kind of structural reforms that have relaunched the German model. Through those reforms, in fact, Germany has become one of the countries that benefit most from global economic integration. As such, Germany has become a reference model for the possibility of a thriving Europe in the global age. However, the same factors that have contributed to the German "global miracle" - the accumulation of savings and gains in competitiveness - are also a "European problem". In fact they contributed to originate the euro crisis and rep- resent elements of danger to the future survival of the euro area. Since the economic success of Germany has translated also into political influence, the other European countries are required to align their economic and social models to the German one. But can they do it? Are structural reforms all that are required? This study shows that the German success depended only in part on the vast array of structural reforms undertaken by German governments in the twenty-first century. -

Nine Lives of Neoliberalism

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) Book — Published Version Nine Lives of Neoliberalism Provided in Cooperation with: WZB Berlin Social Science Center Suggested Citation: Plehwe, Dieter (Ed.); Slobodian, Quinn (Ed.); Mirowski, Philip (Ed.) (2020) : Nine Lives of Neoliberalism, ISBN 978-1-78873-255-0, Verso, London, New York, NY, https://www.versobooks.com/books/3075-nine-lives-of-neoliberalism This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/215796 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative -

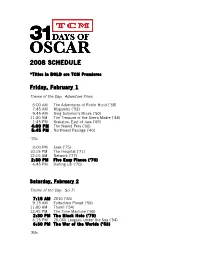

2008 Schedule

2008 SCHEDULE *Titles in BOLD are TCM Premieres Friday, February 1 Theme of the Day: Adventure Films 6:00 AM The Adventures of Robin Hood (’38) 7:45 AM Mogambo (’53) 9:45 AM King Solomon’s Mines (’50) 11:30 AM The Treasure of the Sierra Madre (’48) 1:45 PM Krakatoa, East of Java (’69) 4:00 PM The Naked Prey (’66) 5:45 PM Northwest Passage (’40) ‘70s 8:00 PM Jaws (’75) 10:15 PM The Hospital (’71) 12:15 AM Network (’77) 2:30 PM Five Easy Pieces (’70) 4:45 PM Darling Lili (’70) Saturday, February 2 Theme of the Day: Sci Fi 7:15 AM 2010 (’84) 9:15 AM Forbidden Planet (’56) 11:00 AM Them! (’54) 12:45 PM The Time Machine (’60) 2:30 PM The Black Hole (’79) 4:15 PM 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (’54) 6:30 PM The War of the Worlds (’53) ‘80s 8:00 PM Gandhi (’82) 11:15 PM Atlantic City (’81) 1:15 AM The Trip to Bountiful (’85) 3:15 AM Mephisto (’82) Sunday, February 3 Theme of the Day: Musicals 6:00 AM Anchors Aweigh (’45) 8:30 AM Brigadoon (’54) 10:30 AM The Harvey Girls (’46) 12:15 PM The Band Wagon (’53) 2:15 PM Seven Brides for Seven Brothers (’54) 4:00 PM Gigi (’58) 6:00 PM An American in Paris (’51) ‘90s/’00s 8:00 PM Sense and Sensibility (’95) 10:30 PM Quiz Show (’94) 12:45 PM Kundun (’97) 3:15 AM The Wings of the Dove (’97) Monday, February 4 Theme of the Day: Biopics 5:30 AM The Story of Louis Pasteur (’35) 7:00 AM The Life of Emile Zola (’37) 9:00 AM The Adventures of Mark Twain (’44) 11:15 AM The Eddy Duchin Story (’56) 1:30 PM The Joker is Wild (’57) 3:45 PM Night and Day (’46) 6:00 PM The Glenn Miller Story (’54) ‘20s/’30s 8:00 PM Wings -

ITALY: Five Fascists

Da “Time”, 6 settembre 1943 ITALY: Five Fascists Fascismo's onetime bosses did not give up easily. Around five of them swirled report and rumor: Dead Fascist. Handsome, bemedaled Ettore Muti had been the "incarnation of Fascismo's warlike spirit," according to Notizie di Roma. Lieutenant colonel and "ace" of the air force, he had served in Ethiopia, Spain, Albania, Greece. He had been Party secretary when Italy entered World War II. Now the Badoglio Government, pressing its purge of blackshirts, charged him with graft. Reported the Rome radio: Ettore Muti, whipping out a revolver, resisted arrest by the carabinieri. In a wood on Rome's outskirts a fusillade crackled. Ettore Muti fell dead. Die-Hard Fascist. Swarthy, vituperative Roberto Farinacci had been Fascismo's hellion. He had ranted against the democracies, baited Israel and the Church, flayed Fascist weaklings. Ex-Party secretary and ex-minister of state, he had escaped to Germany after Benito Mussolini's fall. Now, in exile, he was apparently building a Fascist Iron Guard. A Swiss rumor said that Roberto Farinacci had clandestine Nazi help, that he plotted a coup to restore blackshirt power, that he would become pezzo grosso (big shot) of northern Italy once the Germans openly took hold of the Po Valley. Craven Fascist. Tough, demagogic Carlo Scorza had been Fascismo's No. 1 purger. Up & down his Tuscan territory, his ghenga (corruption of "gang") had bullied and blackmailed. He had amassed wealth, yet had denounced the wartime "fat and rich." Now, said a Bern report, Carlo Scorza wrote from prison to Vittorio Emanuele, offering his services to the crown. -

Byron, Orwell, Politics, and the English Language Peter Graham As I

Byron, Orwell, Politics, and the English Language Peter Graham As I began thinking about this lecture for the Kings College IBS it hit home that my first such presentation was 31 years ago, way back in 1982 at Groeningen. Some of the people who were there then are now gone (I think for instance of Elma Dangerfield, so formidable a presence in so small a package, and of Andrew Nicolson, who was celebrating his contract to edit Byron’s prose). Many others who were young and promising then are now three decades less young and more accomplished. Whatever: I hope you’ll bear with a certain amount of nostalgia in the ensuing talk—nostalgia and informality. The goal will be to make some comparative comments on two literary figures familiar to you all—and to consider several texts by these writers, texts that powerfully changed how I thought about things political and poetical when a much younger reader and thinker. The two writers: Eric Blair, better known to the reading public as George Orwell, and Lord Byron. The principal texts: Orwell’s essays, particularly “Politics and the English Language,” and and Byron’s poetico-political masterpiece Don Juan. Let’s start with the men, both of them iconic examples of a certain kind of liberal ruling-class Englishman, the rebel who flouts the strictures of his class, place, and time but does so in a characteristically ruling-class English way. Both men and writers display an upmarket version of the “generous anger” that Orwell attributes to Charles Dickens in a description that perfectly fits Byron and, with the change of one word, fits Orwell himself: “a nineteenth-century liberal, a free intelligence, a type hated with equal hatred by all the smelly little orthodoxies which are now contending for our souls” 2 Byron’s and Orwell’s iconically rebellious lives and iconoclastic writing careers bookend the glory days of the British Empire. -

Executive–Legislative Relations and the Transition to Democracy from Electoral Authoritarian Rule

MWP 2016/01 Max Weber Programme The Peril of Parliamentarism? Executive–legislative Relations and the Transition to Democracy from Electoral Authoritarian Rule AuthorMasaaki Author Higashijima and Author and Yuko Author Kasuya European University Institute Max Weber Programme The Peril of Parliamentarism? Executive–legislative Relations and the Transition to Democracy from Electoral Authoritarian Rule Masaaki Higashijima and Yuko Kasuya EUI Working Paper MWP 2016/01 This text may be downloaded for personal research purposes only. Any additional reproduction for other purposes, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s), editor(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), editor(s), the title, the working paper or other series, the year, and the publisher. ISSN 1830-7728 © Masaaki Higashijima and Yuko Kasuya, 2016 Printed in Italy European University Institute Badia Fiesolana I – 50014 San Domenico di Fiesole (FI) Italy www.eui.eu cadmus.eui.eu Abstract Why do some electoral authoritarian regimes survive for decades while others become democracies? This article explores the impact of constitutional structures on democratic transitions from electoral authoritarianism. We argue that under electoral authoritarian regimes, parliamentary systems permit dictators to survive longer than they do in presidential systems. This is because parliamentary systems incentivize autocrats and ruling elites to engage in power sharing and thus institutionalize party organizations, and indirectly allow electoral manipulation to achieve an overwhelming victory at the ballot box, through practices such as gerrymandering and malapportionment. We test our hypothesis using a combination of cross-national statistical analysis and comparative case studies of Malaysia and the Philippines. -

The American Right Wing; a Report to the Fund for the Republic, Inc

I LINO S UNIVERSITY OF ILLINOIS AT URBANA-CHAMPAIGN PRODUCTION NOTE University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Library Large-scale Digitization Project, 2007. ps.7 University of Illinois Library School OCCASIONAL PAPERS Number 59 November 1960 THE AMERICAN RIGHT WING A Report to the Fund for the Republic, Inc. by Ralph E. Ellsworth and Sarah M. Harris THE AMERICAN RIGHT WING A Report to the Fund for the Republic, Inc. by Ralph E. Ellsworth and Sarah M. Harris Price: $1. 00 University of Illinois Graduate School of Library Science 1960 L- Preface Because of the illness and death in August 1959 of Dr. Sarah M. Harris, research associate in the State University of Iowa Library, the facts and inter- pretations in this report have not been carried beyond the summer of 1958. The changes that have occurred since that time among the American Right Wing are matters of degree, not of nature. Some of the organizations and publications re- ferred to in our report have passed out of existence and some new ones have been established. Increased racial tensions in the south, and indeed, all over the world, have hardened group thinking and organizational lines in the United States over this issue. The late Dr. Harris and I both have taken the position that our spirit of objectivity in handling this elusive and complex problem will have to be judged by the report itself. I would like to say that we started this study some twelve years ago because we felt that the American Right Wing was not being evaluated accurately by scholars and magazine writers. -

IMF Working Paper

WP/00I149 IMF Working Paper The Case against Harry Dexter White: Still Not Proven James M Boughton INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUND © 2000 International Monetary Fund WP/00/149 IMF Working Paper Secretary's Department The Case against Harry Dexter White: Still Not Proven Prepared by James M. Boughton' August 2000 Abstract The views expressed in this Working Paper are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent those of the Th1F or IMF policy. Working Papers describe research in progress by the author( s) and are published to elicit comments and to further debate. Harry Dexter White, the principal architect of the international financial system established at the end of the Second World War, was arguably the most important U. S. government economist of the 20th century. His reputation, however, has suffered because of allegations that he spied for the Soviet Union. That charge has recently been revived by the declassification of documents showing that he met with Soviet agents in 1944 and 1945. Evaluation of that evidence in the context of White' s career and worldview casts doubt on the case against him and provides the basis for a more benign interpretation. JEL Classification Numbers: B31, F33 Keywords: Harry Dexter White; Bretton Woods; McCarthyism Author's E-Mail Address: [email protected] , This paper was prepared while I was on leave at St. Antony's College, University of Oxford. I would like to thank Shailendra Anjaria, Bruce Craig, Stanley Fischer, Amy Knight, Roger Sandilands, and seminar participants at the University of Strathclyde for comments on earlier drafts. This work also has benefited from many personal recollections, for which I thank Robert Cae, David Eddy, Sir Joseph Gold, Sidney Rittenberg, Paul Samuelson, Ernest Weiss, and Gordon Williams. -

The American Legion Magazine, P

THE AMERICAN SEE PAGE 14, REDS IN KHAKI LEGION How communists operated as MAGAZINE members of our Armed Forces OCTOBER 1952 The American Legion at New York . .An account of the National Convention . Starting Page 29 - SEAGRAM'S 7 CROWN. BLENDED WHISKEY. 86.8 PROOF. 65% GRAIN NEUTRAL SPIRITS. S E A G R A M D I ST I L L E R S CORP., N. Y. ' CARSMIN THEIR BESTON THEBEST GASOLINE , 1952 BUICK Roadmaster with the Fireball 8 engine — a valve-in-head design that "makes the most of high compression." Dynafiow Drive and optional Power Steering make driving the Roadmaster an almost effortless pleasure. 1932 LA SALLE had an automatic vacuum- operated clutch, and a unique shock ab- sorber system. You varied the stiffness of the shocks to fit changing road conditions. ETHYL" With their polished leather seats and bright brass trim, yesterday's automobiles looked mighty good to their owners. But Grandpa will tell you they did not have enough power under the hood. That's one thing today's car owner isn't likely to complain about. The combination of a mod- ETHYL ern high compression engine and "Ethyl" gaso- line gives plenty of power. CORPORATION "Ethyl" gasoline is high octane gasoline. It New York 17, New York helps high compression engines develop top 1921 HAYNES had advanced fea- Ethyl Antiknock Ltd., in Canada many power and efficiency. It's the gasoline you ought tures including "finger-touch" starting . there is a powerful differ- lever and light switch on the dash. The to buy. Remember body was aluminum under the paint job. -

Harry Dexter White, Arguably the Most Important US Government Economist of the 20 Century, Acquired a Bifurcated Reputati

- 3 - 1_ INTRODUCTION Harry Dexter White, arguably the most important U.S. government economist of the 20th century, acquired a bifurcated reputation by thc end of his short life in 1948. On the positive side, he was recognized along with John Maynard Keynes as the architect of the postwar international economic system. On the negative, he was accused of betraying U.S. national interests and spying for the Soviet Union before and during World War II. Although he was never charged with a crime and defended himself successfully both before a federal Grand Jury and through open testimony before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), the accusations were revived five years later, in the late stages of the McCarthy era, and never quite died away. Four recently published books have revived the espionage charges against White.' The new allegations are based primarily on a series of cables sent between Soviet intelligence agents in the United States and Moscow. Many of those cables were intercepted by U.S. intelligence, were partially decoded in the years after the war through the then-secret and now famous VENONA project,3 and have recently been declassified and released to the public. Selected other cables and documents from the Soviet-era KGB files were made available for a fee to two writers, Allen Weinstein and Alexander Vassiliev, by the Russian government. Far more extensive data from those files were smuggled out of Russia in the 1990s by a former agent, Vasili Mitrokhin. On first reading, these various releases appear to offer damning new evidence. -

Covering the Ukraine Crisis on the Ground with Maria Turchenkova, Paul Klebnikov Fellow Harriman Magazine Is Published Biannually by the Harriman Institute

the harriman institute at columbia university FALL 2015 Covering the Ukraine Crisis On the Ground with Maria Turchenkova, Paul Klebnikov Fellow Harriman Magazine is published biannually by the Harriman Institute. Managing Editor: Ronald Meyer Editor: Masha Udensiva-Brenner Comments, suggestions, or address changes may be e-mailed to Masha Udensiva-Brenner at [email protected]. Cover photo © Maria Turchenkova: Protestor in Kyiv’s Maidan Nezalezhnosti (Independence Square) during clashes with riot police in late January 2014 Photo on this page © Maria Turchenkova: Pro-Russian fighters searching for the pilots of a Ukrainian jet shot down by rebels near the city of Yenakievo Design and Art Direction: Columbia Creative Harriman Institute Alexander Cooley, Director Alla Rachkov, Associate Director Ryan Kreider, Assistant Director Rebecca Dalton, Program Manager, Student Affairs Harriman Institute Columbia University 420 West 118th Street New York, NY 10027 Tel: 212-854-4623 Fax: 212-666-3481 For the latest news and updates about the Harriman Institute, visit harriman.columbia.edu. Stay connected through Facebook and Twitter! www.twitter.com/HarrimanInst www.facebook.com/TheHarrimanInstitute FROM THE DIRECTOR am delighted to write my first note of introduction forHarriman Magazine and honored to be taking over the directorship from Tim Frye. I am deeply grateful I for his many years of thoughtful and highly effective leadership. Under Tim the Institute went from strength to strength, affirming its global reputation as a leading center of scholarship and a vibrant hub for Eurasia-related issues. I am looking forward to continuing our long tradition of supporting academic excellence and encouraging research, investigation, and debate on a wide variety of regional issues and challenges.