Spirit Mountain: the First Forty Years

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Attraction Name Location Open/Closed Notes Buck Hill Burnsville Closed Closed for the Season Canterbury Downs Shakopee Closed Cl

Attraction Name Location Open/Closed Notes Buck Hill Burnsville Closed Closed for the season Canterbury Downs Shakopee Closed Closed for an unspecified period of time Chanhassen Dinner Theatre Chanhassen Closed All performances closed until further notice Como Park Zoo & Conservatory Saint Paul Closed Closed until further notice Crayola Experience Bloomington Closed Closed until further notice Eagan Art House Eagan Closed Until further notice Eagan Community Center Eagan Closed Closed until further notice Emagine Eagan Eagan Closed Until further notice FlyOver America Bloomington Closed Closed until further notice Good Times Park Eagan Closed Until further notice All venues (State Theatre, Orpheum Theatre, Pantages Theatre) have cancelled or are Hennepin Theatre Trust Minneapolis Closed rescheduling shows to a later date. All parks programs and events are cancelled until further notice. Parks and trails remain open. All Lebanon Hills (Park and Visitor Center) Eagan Closed facilities are closed until further notice. Closed through May 1, 2020 ***Red Cross Blood Drive to be held in the North Atrium on April Mall of America Bloomington Closed 30 & May 14. Go to https://rcblood.org/33Xx9Tu to reserve your time. The donation site is scheduled to be open 10AM-4PM on dates listed*** Minneapolis Institute of Art Minneapolis Closed Until further notice Minnesota History Center Saint Paul Closed ALL MN Historical Society sites and museums are closed until further notice. Minnesota Zoo Apple Valley Closed Virtual Farm Babies - Apr 13-May 17 Visit mnzoo.org Mystic Lake Casino Prior Lake Closed Closed until further notice Nickelodeon Universe Bloomington Closed Until further notice Ordway Center for the Performing Arts Saint Paul Closed Closed until further notice. -

Highway 23 / Grand Avenue Corridor Study Analysis & Recommendations for STH 23 in Duluth, Minnesota

Highway 23 / Grand Avenue Corridor Study Analysis & Recommendations for STH 23 in Duluth, Minnesota Prepared by the Duluth-Superior Metropolitan Interstate Council December 2013 Executive Summary This document represents the findings of a corridor study of the segment of MN State Highway 23 between Becks Road and Interstate 35 in Duluth, Minnesota. This roadway, also known as “Grand Avenue” serves as a principal arterial in West Duluth and is both an important regional and local transportation corridor. The study focused on how well the corridor is currently serving multiple modes of transportation, but it also considered the potential for redevelopment and increasing traffic. The findings indicate that the corridor is not sufficiently serving non-motorized forms of transportation, given potential demand. The findings also suggest, however, the possibility for a level of future growth in West Duluth that that could increase traffic and worsen conditions for all users under the existing constraints to expand the roadway. The findings of this study have led to a series of recommended improvements (found in Section 4 of this document) which have been presented to the Minnesota Department of Transportation (MnDOT) and the City of Duluth. These recommendations represent a menu of short– and mid-term options that could improve the existing corridor for both motorized and non-motorized users. The majority of these improvements can be implemented within the existing public right-of- way and with moderate levels of investment. Grand Avenue / Hwy 23 Corridor -

Duluth-Superior Metropolititan Interstate Committee

Duluth-Superior Area Transit Vision - 1998 Table of Contents I. Introduction............................................................................................................................ 1-1 II. DTA Mission, Goals, Objectives and Standards ................................................................... 2-1 III. Demographic and Socio-Economic Characteristics .............................................................. 3-1 IV. DTA Financial and Capital Summary ................................................................................... 4-1 V. DTA System Analysis............................................................................................................ 5-1 • Ridership Fixed Route System ................................................................................ 5-10 • Route Profiles .......................................................................................................... 5-21 VI. Transit Model Summary........................................................................................................ 6-1 VII. Marketing Plan ..................................................................................................................... 7-1 • Introduction................................................................................................................ 7-1 • Market Situation ........................................................................................................ 7-1 • Product Situation....................................................................................................... -

2020-Chamber-Directory Web.Pdf

Your Real Estate Experts! Dick Wenaas Greg Kamp Tommy Jess Mary Alysa JoLynn Kathy David Pam Archer Bellefeuille Binsfield Bjorklund Cooper Cortes Corbin Dahlberg Deb Ginger Cathy Sue Candi Melissa Brenda Mark Dreawves Eckman Ehret Erickson Fabre Fahlin Gregorich Honer Doug Tom Sharon Shaina Anissa Peter Kriss Kman Little McCauley Nickila Priley Rozumalski Sutherland Blythe Jonathan Patry Jeanne Ron Claude Chris Thill Thornton Truman Tondryk Tondryk Wenaas Wilk Duluth (218) 728-5161 - Cloquet (218) 879-1211 - Superior (715) 394-6671 • www.cbeastwestrealty.com vi 2020 Duluth Area Chamber of Commerce x Welcome to Our Beloved Community Welcome .................................. 1 uluth is a vibrant community filled with remarkable people and places. We enjoy Duluth History.......................... 2 an extraordinary city that supports, cares for and creates opportunities for all Duluth at a Glance .................. 5 Dof our citizens. If you have arrived on our shores, we are happy to have you join us. If you are Housing .................................... 6 considering making the Duluth area your home or place of business, wait no longer. Economy ................................ 10 We are ready to help you settle in for a lifetime. Building Our City .................... 12 This is one of the most beautiful places you are ever going to experience. We are ready to show it off, and that is why our Chamber is making this Community Guide available Education ............................... 16 to you. We believe the more you know about our Shining City on the Hill, the more Financial ................................ 20 you will be drawn to it. You will enjoy this big city with a small-town personality – Government ........................... 26 a rugged outpost with a cosmopolitan flair. -

Spirit Mountain Task Force

SPIRIT MOUNTAIN TASK FORCE RECOMMENDATIONS MARCH 2021 0 SPIRIT MOUNTAIN TASK FORCE MEMBERS Co-Chairs: City Councilor Arik Forsman, Parks, Libraries and Authorities Chair City Councilor Janet Kennedy, Fifth District Task Force Members: Matt Baumgartner Amy Brooks Barbara Carr Michele Dressel Mark Emmel Daniel Hartman Hansi Johnson Noah Kramer Dale Lewis Sam Luoma Chris Rubesch Scott Youngdahl Aaron Stolp, Spirit Mountain Recreation Area Authority Board Chair Wayne DuPuis, an Indigenous representative with expertise in Indigenous cultural resources Ex officio members: Gretchen Ransom, Dave Wadsworth and Jane Kaiser (retired), directors at Spirit Mountain Anna Tanski, executive director of Visit Duluth Tim Miller and Bjorn Reed, representatives of the Spirit Mountain workforce selected in consultation with the AFSCME collective bargaining unit 1 CONTENTS Spirit Mountain Task Force Members ........................................................................................................................... 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Executive Summary ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 Fulfilling the Charge ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Business -

Minnesota Official Visitor Guide

OFFICIAL VISITOR GUIDE Duluth2018 MINNESOTA OFFICAL VISITOR GUIDE | VISITDULUTH.COM 1 find it IN DULUTH This city is a place like no other. A breathtaking horizon where the water of Lake Superior meets the sky. Rocky cliffs and pristine forests with miles of trails to explore. A thriving community where you can take in a show, enjoy a meal and stay in comfort no matter where your plans take you. You’ll find it all in Duluth. NEW LOCATION - VISIT DULUTH Phone: (218) 722-4011 CONNECT WITH US 225 W. Superior St., Suite 110 1-800-4-duluth (1-800-438-5884) Duluth, MN 55802 Hours: Open 8:30-5:00pm Email: [email protected] Monday through Friday Online: www.visitduluth.com Visit Duluth is Duluth’s officially recognized destination marketing organization. Chartered in 1935, it represents over 400 businesses that make up Duluth’s tourism industry and is dedicated to promoting the area as one of America’s great vacation and meeting destinations - providing comprehensive, unbiased information to all travelers. Table of Contents Lakewalk + Lake Superior ..........................................4 Watch the Ships ........................................................40 Exploration + Adventure ............................................6 Sports + Recreation ..................................................42 Four Seasons of Fun .................................................12 Parks + Trails .............................................................46 Arts + Entertainment /HART ....................................14 A Place to Remember ...............................................48 -

Spirit Mountain: the First Forty Years

SPIRIT MOUNTAIN: THE FIRST FORTY YEARS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA DULUTH BY STEPHEN PHILIP WELSH IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF LIBERAL STUDIES DAVID E. BEARD, Ph.D. MAY 15, 2015 Spirit Mountain: The First Forty Years Submitted as Partial Fulfillment Of Requirements for the Degree Master of Liberal Studies Candidate Signature 3t;iUlL2 Ll-e)~ Stephen P. Welsh Supervising Faculty Signature~ ) f' iJ David E. Beard, Ph.D. Date Approved _ -'--M=--41_,._ __\------:;. ,·--=--- ~ ~·-C"------ -- Table of Contents Preface i. Introduction ii. Preliminaries 1 A Tentative Start 2 Terrain Encumbrances 7 Native American Concerns 9 Phase I 12 Chair Lifts 17 The Ski Chalet 19 Initial Ski Area Successes 20 Snowmaking and Water Supply 22 Expanding Services 23 Topographical Realities 24 Phase II 25 Express Lift I 30 Phase III 34 Adventure Park 36 Affiliated Organizations 39 Weather and Profits 41 Proposed Golf Course and Hotel 43 Concluding Remarks 44 Appendices References Preface This brief retrospective of the first forty years of existence of the Spirit Mountain Recreation Area in Duluth has been undertaken as an aspect of a graduate degree program at UMD. The historical account is my personal Capstone Project required for the granting of the Master of Liberal Studies degree. Having been retired from a teaching career for a few years, and feeling the need for an academic "stirring-up", I enrolled in 2011 in a single course through Continuing Education at UMD. It was there that I learned about a revamped MLS degree program that hoped to attract senior citizens who may have post-retirement time and an inclination to pursue a graduate degree. -

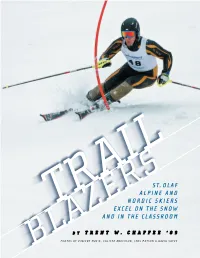

St.Olaf Alpine and Nordic Skiers Excel

IL A S R R ST. OLAF E ALPINE AND T NORDIC SKIERS Z EXCEL ON THE SNOW LA AND IN THE CLASSROO M B Y T R E N T W . C H A F F E E ’ 0 9 B PHOTOS BY VINCENT MUZIK, CALISTA ANDERSON, JENS MATSON & DAVID SAYRE onnor Lund was strapped into his first pair of skis at the age of two. By age five , he was a member of his first ski racing skiing that began on Manitou Heights in 1886 with the C team at Buck Hill, a popular ski area in Burnsville, founding of the St. Olaf Ski Club. The club hosted its first ski Minnesota. It’s been “downhill ” ever since. meet in 1912 and drew the best amateur skiers from across Lund, a senior economics major who is pursuing an the Midwest. The skiers were attracted by Pop Hill Slide, a emphasis in finance, is co-captain of the St. Olaf men’s alpine wooden ski jump . Pop Hill was reconstructed in steel in 1913, ski team . As his final St. Olaf season gets underway, Lund increasing its length and potential jumping distances to more steps into the starting gates of black diamond courses, digs his than 100 feet, and renamed Haugen Slide in honor of world poles into the battered snow and races against the clock down champion ski jumper Anders Haugen , who supe rvised the ren - treacherous courses with the freezing wind in his face, soaring ovation. St. Olaf hosted popular ski events throughout the past gates while avoiding potholes, ice spots and “waterfalls” early 20th century . -

Minneapolis-Visitor-S-Guide.Pdf

Minneapolis® 2020 Oicial Visitors Guide to the Twin Cities Area WORD’S OUT Blending natural beauty with urban culture is what we do best in Minneapolis and St. Paul. From unorgettable city skylines and historic architecture to a multitude o award-winning ches, unique neighborhoods and more, you’ll wonder what took you so long to uncover all the magic the Twin Cities have to o er. 14 Get A Taste With several Minneapolis ches boasting James Beard Awards, don’t be surprised when exotic and lavor-packed tastes rom around the globe lip your world upside down. TJ TURNER 20 Notable HAI Neighborhoods Explore Minneapolis, St. Paul and the surrounding suburbs LANE PELOVSKY like a local with day trip itineraries, un acts and must-sees. HOSKOVEC DUSTY HAI HAI ST. ANTHONY MAIN ANTHONY ST. COVER PHOTO PHOTO COVER 2 | Minneapolis Oicial Visitors Guide 2020 COME PLAY RACING•CARDS•EVENTS Blackjack & Poker 24/7 Live Racing May - September • Smoke - Free Gaming Floor • • Chips Bar Open Until 2 AM • In a fast food, chain-driven, cookie-cutter world, it’s hard to find a true original. A restaurant that proudly holds its ground and doesn’t scamper after every passing trend. Since 1946, Murray’s has been that place. Whether you’re looking for a classic cocktail crafted from local spirits or a nationally acclaimed steak, we welcome you. Come in and discover the unique mash-up of new & true that’s been drawing people to our landmark location for over 70 years–AND keeps them coming back for more. CanterburyPark.com 952-445-7223 • 1100 Canterbury Road, Shakopee, MN 55379 mnmo.com/visitors | 3 GUTHRIE THEATER 10 Marquee Events 78 Greater Minneapolis Map 74 Travel Tools 80 Metro Light Rail Map 76 Downtown Maps 82 Resource Guide ST. -

Skyline Parkway Corridor Management Plan

June 2015 Update SKYLINE PARKWAY CORRIDOR MANAGEMENT PLAN City of Duluth Department of Planning & Development in conjunction with LHB Engineers & Architects Arrowhead Regional Development Commission Mary Means & Associates Updated – May 2015 Patrick Nunnally This corridor management plan has been prepared with funding from the State Scenic Byways Program, Minnesota Department of Transportation, and the City of Duluth, Department of Planning & Development "Where in all this wide world could I find such a view as this?” Samuel F. Snively It has been 100 years since Samuel Snively donated the road he built, with its ten wooden bridges crossing Amity Creek, to the Duluth Park Board in order to establish the eastern end of what was to become Duluth's famed boulevard parkway system. During the ensuing century, this remarkable thoroughfare has had many names – Duluth's Highland Boulevard, Terrace Parkway, Rogers Boulevard, Skyline Drive, Snively Boulevard and, officially, Skyline Parkway – yet its essential nature has remained unchanged: "A drive that is the pride of our city, and one that for its picturesque and varied scenery, is second top none in the world ..." (1st Annual Report of the Board of Park Commissioners, 1891). From its inception, the Parkway has formed the common thread which has bound this community together, creating the 'backbone' of the city's expansive park system. Its 46 miles of road range from semi-wilderness to urban in context, and its alignment, following the geography which defines Duluth, provides a unique perspective on what one early twentieth century observer referred to as this "God-graded town". Because Skyline Parkway grew with Duluth, its history – and the physical characteristics which reflect this history – must be preserved. -

Annual Air Monitoring Network Plan for the State of Minnesota

Appendix A 2015 Air Monitoring Site Descriptions Summary The following pages are descriptions of MPCA Air Quality Monitoring Sites. Each site has its own page and each page is listed in the Table of Contents. At the top of each page is the city where the site is located and the site name. Below the heading there is identification information for each site, including the AQS site identification number, MPCA site identification number, address, city, county, location setting, latitude, longitude, elevation, and year established. The next section of the page has a table of possible monitoring parameters and a map of Minnesota. Parameters that are monitored at the particular site are indicated in the table. The Minnesota map portrays the approximate location of the site within the state. Next there is a smaller scale map of the site. This map indicates the major roadways or other geographic features that are near the site. It is followed by a recent picture of the monitors in their current location. The final section of the page contains a short site description, a list of monitoring objectives, and any changes proposed for the site. Federal Regulation 40 CFR § 58.10(a)(1) Annual monitoring network plan and periodic network assessment Beginning July 1, 2007, the State, or where applicable local, agency shall adopt and submit to the Regional Administrator an annual monitoring network plan which shall provide for the establishment and maintenance of an air quality surveillance system that consists of a network of SLAMS monitoring stations including FRM, FEM, and ARM monitors that are part of SLAMS, NCore stations, STN stations, State speciation stations, SPM stations, and/or, in serious, severe and extreme ozone nonattainment areas, PAMS stations, and SPM monitoring stations. -

Dakota County Recreational Directory

Dakota County Recreational Directory Recreational Resources for Children and/or Adults with Disabilities April 2015 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents 2 How to use this directory 3 Camps/Social Recreational Programs 4 Programs for the Arts 10 Local Civic/Disability Organizations 13 Adapted/Recreational Sports 14 Fishing & Hunting 16 Horseback Riding 16 Karate 18 Skiing 18 Swimming 19 Special Olympics 21 Vacation/Travel 22 Outdoor Recreational Equipment 23 Transportation 25 Additional Community Resources 26 Child Care Resources 29 Appendix 30 2 HOW TO USE THIS DIRECTORY The following directory is designed to assist families served by the Dakota County Developmental Disabilities Section in learning about various social/recreational options available for individuals with special needs. You will find that many of the programs listed here are designed specifically for children and/or adults with developmental and sometimes physical disabilities. This does not mean that programs designed for all children are not appropriate or desirable for your child with special needs. In the Appendix you will find listings of local Park & Recreation Offices, Community Education and other local organizations designed for all local citizens that provide group activities, classes or events which you might explore. Keep in mind that each city or cooperative will usually have an Adaptive Recreation Coordinator to assist and advise you and your children in how to best access their program. Local churches, should you belong, often are a good resource for integrated social activities. Also, you might wish to consult with the Adaptive Physical Education teacher/IEP case manager listed on your child’s IEP.